Over the past few years, we have been told that America’s police and criminal justice process are systemically racist.

The police, it is implied, are inherently unfair in their treatment of African Americans and other minorities. Prosecutors and the courts, it has often been suggested, are much harsher in their treatment of certain groups. Systemic racism, some tell us, explains different outcomes when it comes to criminal justice.

The narrative of systemic racism is nonsense - but it needs to be exposed as nonsense or it risks becoming dangerous nonsense.

Rafael Mangual, who came to Jackson last week, is a senior fellow of the Manhattan Institute. His book, Criminal (In)Justice reveals that the supposed biases of the criminal justice system are nothing of the sort.

According to Mangual’s research, different outcomes in the criminal justice system are not reflective of any supposed biases of the system. They reflect differences in behavior.

Crime in America, particularly violent crime, is hyper-concentrated, both geographically and demographically. This might be an uncomfortable truth for some, but the truth needs to be acknowledged. Moreover, as Mangual, and others have shown, the victims of violent crime in America are disproportionately African American.

When left unchallenged, the narrative of systemic racism undermines law enforcement It has enabled radical activists – often aided by well-meaning conservatives – to advance an anti-police / anti-prison agenda over the past decade.

Citing the fallacy of police discrimination, activists have successfully demanded that the police be less proactive in arresting wrongdoers. There has been a large decline in the number of arrests made in America each year since 2010.

Radical reformers have also demanded that public prosecutors go easy on those that break the law. They have even advanced an anti-prison agenda, claiming that felons should not face jail time. America’s prison population is today 25 percent lower than it was in 2011, and the incarceration rate in Mississippi has fallen significantly in the past two decades.

These reforms, introduced in the mistaken belief that America’s criminal justice system is discriminatory and unfair, have had disastrous consequences – especially for the minority communities that the reformers claimed they want to help.

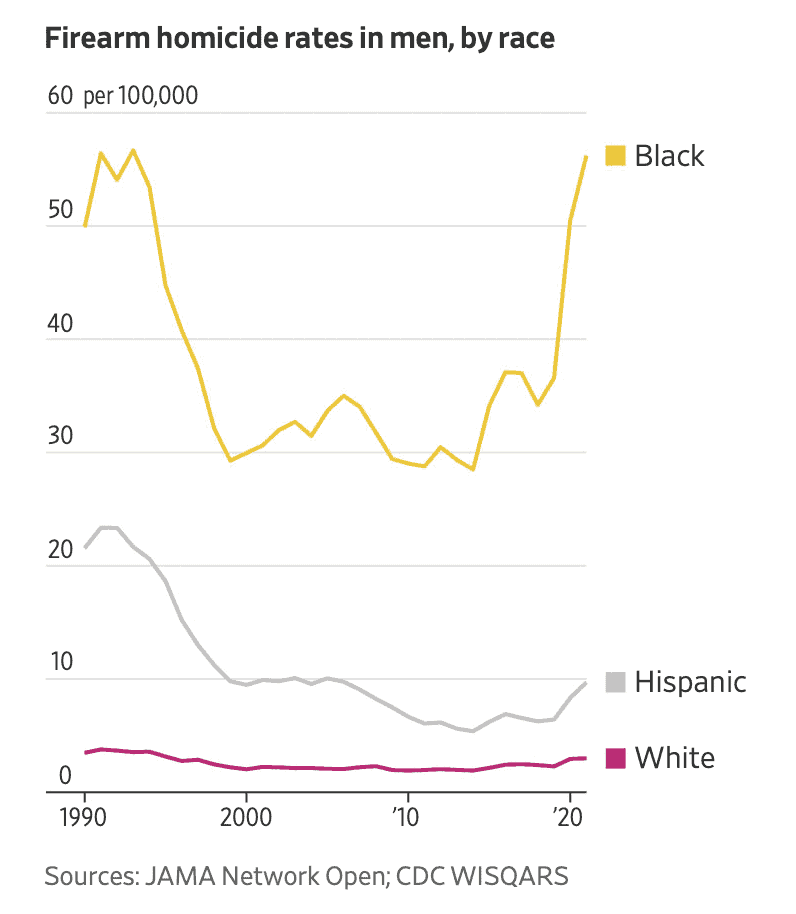

Below is a graph from the Wall Street Journal, citing data from JAMA. It shows the firearm homicide rates for men by race.

During the 1990s, when get tough measures were taken to reduce violent crime, the firearm homicide rate for African American men fell dramatically. When the current wave of reforms started to take effect in about 2015, homicide rates for African American men soared.

Is the criminal justice system, now that it has fewer proactive arrests, less prosecution and shorter sentencing, doing a better job today for African American men?

Here in Mississippi in 2014-16, well-meaning conservatives introduced legislation to overhaul sentencing laws. They did so claiming that there were better ways to reduce crime than by filling the prisons.

How did that work out?

In 2013, the year before policies were introduced to reduce the rate of incarceration, 28 people were murdered in Jackson per 100,000 people. By 2021, almost four times that many people, 101 per 100,000 people in our capital city were homicide victims.

Despite what is often claimed, Mississippi does not have a problem with over-incarceration. Since 2002, the prison incarceration rate in our state fell from 1,207 per 100,000 to 916 per 100,000 by 2021. Mississippi’s incarcerated population decreased from 21,008 on January 3, 2014, to 16,931 by January 3, 2022, a decrease of 19.4 percent.

The reduction in the incarceration rate in our state has been mirrored by a significant rise in violent crime. If you quit locking up bad people, you free them to do bad things to good people.

Rather than measure the rate at which we lock people up relative to the number of people in our state, perhaps we ought to measure the incarceration rate against the level of criminality in our state.

There is nothing credible about claims that America’s criminal justice process is systemically prejudiced. Such claims must not be allowed to undermine the effectiveness of the fight against crime.

Nor is there anything good or noble about misguided criminal justice reforms that allow offenders to reoffend. It is time that these truths were spelled out.