Mississippi added more than 14,000 jobs over the past year while the state’s unemployment rate sits at 4.8 percent, a near historic low.

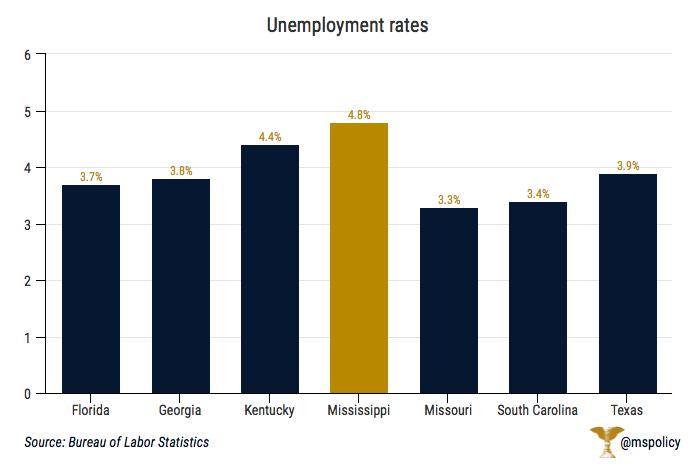

Overall, the national unemployment rate sits at 3.9 percent for the month of August.

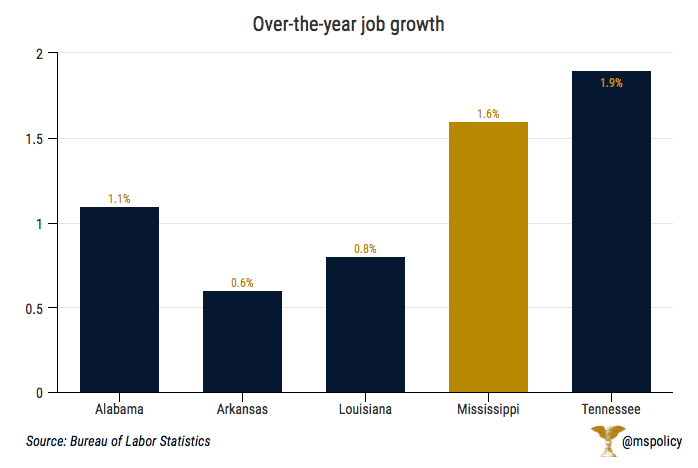

Statistically, Mississippi’s 1.6 percent over-the-year job growth compared favorably among the state’s neighbors.

Only Tennessee, whose payrolls grew by 1.9 percent saw greater improvement in terms of job numbers, percentage wise, than Mississippi. Alabama grew by 1.1 percent while Arkansas and Louisiana grew by .6 percent and .8 percent, respectively.

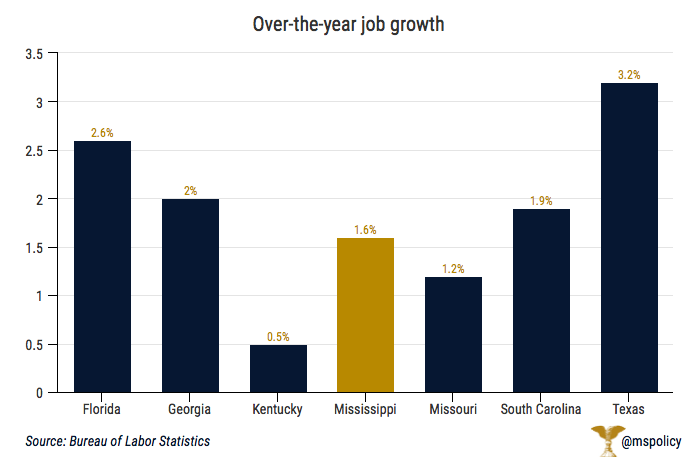

Outside of Mississippi’s immediate neighbors, we saw strong gains in most SEC states, with Kentucky being an outlier among this group.

Mississippi's unemployment rate

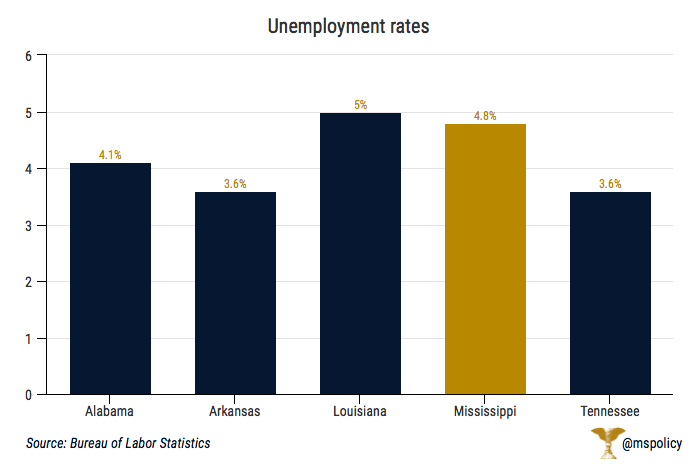

At 4.8 percent, Mississippi’s unemployment rate remains near the state’s historic low of 4.6 percent. That occurred just this past December. But among Mississippi’s neighbors, every state but Louisiana had a lower unemployment rate.

Though low, and down from just a few years ago, Mississippi’s unemployment rate is still 47th nationally.

Among the other SEC states, we see unemployment rates ranging from 3.3 percent in Missouri to 4.4 percent in Kentucky.

Within Mississippi, the following counties had unemployment rates under 4.2 percent (for July 2018): Rankin (3.6%), Union (3.7%), Desoto (4%), Lamar (4.1%), Madison (4.1%), and Pontotoc (4.2%). The following had unemployment rates above 9.1 percent: Humphreys (9.4%), Wilkinson (10.1%), Holmes (10.3%), Claiborne (10.8%), and Jefferson (15.2%).

Graduating from high school, obtaining employment, and getting married before having children is still the best path out of poverty.

A recent essay in the New York Times tells the story of a life in poverty. This same story could be told of countless individuals in Mississippi.

Unfortunately, something that could be productive for a larger discussion misses that mark. Under the headline, “Americans want to believe jobs are the solution to poverty. They’re not,” we learn about the struggles of Vanessa Solivan, a home health aide in New Jersey.

Vanessa is a single-mom with three children. As a home health aide, she makes between $10 and $14 per hour. She works part-time, between 20 and 30 hours a week. If we took the average of both those numbers, 25 hours a week at $12 an hour, Vanessa would make a little more than $15,000 a year. Even with the Earned Income Tax Credit, before other welfare programs, she would only be bringing in about $20,000 per year.

No one would argue that is not enough to live on, particularly with three kids. Though, Vanessa’s story isn’t quite aligned with the headline.

Full-time jobs, and a two-parent household, are the solution to poverty; not single-parents with part-time jobs

Why is Vanessa only working part-time? She wants to work more hours but can’t. Several years ago, during the Obamacare debate, Republicans rightly were arguing that these new requirements will only encourage employers to prefer part-time workers. We often talk about the law of unintended consequences when it comes to government policy, but this was a consequence you didn’t need a public policy degree in order to predict. But policy makers just chose to ignore it. Or they blamed business owners for the terrible sin of “worrying about their bottom line.”

If Vanessa were working full-time, her income would be closer to $30,000, roughly a third more income to make her household budget a little more manageable.

While there is certainly nobility in working in healthcare, if Vanessa had a better K-12 education than most who grow up in poverty, could she have been better prepared for a more sustainable career path? Perhaps if she had had access to a voucher, tax credit scholarship, or a charter school, her career would have gone in a different direction and she would have a higher income today. But alas, to most on the left, the path to better public education outcomes will only come from spending more money, despite decades of evidence to the contrary

And what about the fathers of Vanessa’s three children? One is dead from a gunshot wound after spending time in prison. The others provide occasional support, but nothing of substance. Unfortunately, this is a story that is very common in America today. Since the 1960s, when our country adopted most welfare programs in the name of a “Great Society,” out-of-wedlock birth rates have gone from about 5 percent to over 40 percent. In Mississippi, it’s 53 percent.

And disastrous results have followed

According to newly released Census data, only 17 percent of the lowest fifth income earners, those who make less than $25,000, are married. Conversely, 76 percent of the highest fifth, those with an income above $125,000, are married.

Now, if Vanessa had followed what conservatives refer to as the “success sequence,” and obtained employment and got married before having children, the New York Times writer would have had quite a different story. Even if we assume she is working the same job, and her husband enjoyed a comparable salary, the couple would be making about $48,000 per year working full-time.

The underlying message in a story like this from the New York Times is that the economy does not work for everyone. Jobs aren’t the answer. No one is dismissing the plight of those who struggle. But simply providing more welfare benefits will not move Vanessa, or others like her, off this generational cycle of poverty.

Rather, it starts with smart policy, like the Hope Act that Mississippi adopted in 2017, modeled after 1990s era “welfare-to-work” reforms. The new law requires able-bodied individuals without dependents to obtain employment or job training to continue receiving food stamps. And the path up the economic ladder includes the work of churches, non-profits, and the private sector reaching out and providing a helping hand in ways that only they can.

Those who start out in poverty certainly start out further behind. But we know there are paths to a better future. The problem is that the government, unfortunately, is usually more of a barricade than a guiding light on that path to more prosperity and opportunity.

This column appeared in the Madison County Journal on September 20, 2018.

The city of Pearl has taken a prudent approach to the city’s finances over the past 15 months, choosing to reduce spending rather than raise taxes.

For the next fiscal year, the city’s millage rate remains at 27.5 mills and the millage rate for the Pearl School District remains at 60.40 mills.

In 2017, when the current mayor and board of alderman took office, the city’s budget was around $22 million. Last year, the city trimmed it to $18.9 million.

“I knew the struggles the city was having were daily operations,” Mayor Jake Windham said. “We have good revenues. I had a gut feeling we can run a lean budget so we did our due diligence and took the most stringent route. I felt we could dig deep while still doing the necessary things.”

This year, once again, the city did not raise taxes.

“When you decline financially, it makes everything suffer,” Windham added. “We hold ourselves accountable. Raising taxes aren’t necessarily the answer. I didn’t think we had a lean budget like you have at home. We worked with city employees and department heads to create a culture of fiscal responsibility for the city. And they bought in and we were able to turn everything around. This is the first time in eight years we didn’t borrow to pay bills.”

The savings came through reviewing every dollar that was spent and making smart decisions, like implementing a purchase order system.

But this included making difficult choices.

“You can’t cut enough office supplies when you are short falling $100,000 a month,” Windham said. “We knew we had to send people home. We had 20 leave through attrition and had 15 more layoffs.”

For the next year, the budget will increase in key areas.

“As we build revenues, we concentrate on the fundaments of government, then branch out,” Windham said. “We’ve increased where necessary, including road repairs and the clean up of the community.”

The city will also incur new expenses. They are picking up the two percent increase that city employees will pay into the Public Employment Retirement System and health insurance has gone up 18 percent over the previous year.

The city is also on the hook for $800,000 for its share of the Pearl-Richland Intermodal project that will construct a bridge over the railroad tracks on South Pearson Road.

But Windham says the city is on the right track.

“We are making bond payments we weren’t and we look to come in under budget.”

This morning, a coalition of 30 free market policy groups, including the Mississippi Center for Public Policy, sent a letter to House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Kevin Brady objecting to any expansion of the federal electric vehicle tax credit.

The letter encourages Chairman Brady to reject attempts by the EV lobby and their allies in Congress to slip a tax-credit cap increase into upcoming spending packages. Congress has a responsibility to spare American taxpayers increased economic harm from a subsidy that benefits only those who can afford expensive electric vehicles.

American Energy Alliance President Thomas J. Pyle made the following statement:

“The electric vehicle tax credit subsidizes expensive vehicles that only a fraction of wealthy Americans want and that do not necessarily pollute less than modern internal combustion engines.

“Why should a typical middle class American family — with a median annual income of $44,000 — subsidize the lifestyles of the rich and famous? Political leaders should recognize that Americans can make their own decisions about how to spend their money and what cars they want to drive. We shouldn’t give handouts to wealthy individuals to help defray the cost of their luxury vehicles.”

The full letter can be found here.

This press release is from the American Energy Alliance.

The first public charter school opened in Mississippi more than two decades after our nation’s first charter school welcomed students in Minnesota. Today, five years after state legislators finally allowed charter schools to operate in our state, it is safe to say that charter approvals continue at the same snail’s pace.

The Mississippi Charter Authorizer Board recently voted to allow a new school, Ambition Prep, to open in West Jackson next year. It was the only school to be greenlighted by the state in this cycle, though two other proposals were tabled for consideration in October.

In 2018, 16 different operators proposed opening a total of 17 schools across the state from the Coast to Jackson to the Delta. The prior two years, 18 operators filed similar letters of intent to begin the charter school application process.

But when Ambition Prep opens it will be just the sixth charter school in the state, with all but one in Jackson.

Educational entrepreneurs are interested in opening schools. And parents are interested in options. Despite the small footprint, 15-20 percent of public school students in Jackson who attend a grade that is also served by a charter school are enrolled in charter schools. And that number will only increase.

Yet in light of the slow-growing sector, limited enrollment, and swelling wait lists, we wonder whose opinion matters more when it comes to educational choice – government or parents’?

Our charter law emphasizes a rigorous application process and “high quality” schools. Yet this bottleneck has created much greater pressure for early charter schools and a less dynamic and attractive environment for new operators to enter. The restriction of charter applications to D and F-rated districts most recently left the authorizer board torn between rejecting or approving an application faster than they would like to, in the event the district’s grade changes and invalidates the nearly successful proposal.

In advance of the release of school grades, state superintendent Carey Wright cautioned against judging charter schools too quickly, since they face unique start-up and environmental challenges along with the added pressure of serving students far behind academically. But the law makes this reasonable approach difficult: schools have a very narrow timeframe in which to meet certain state-determined guidelines or be shut down.

A different approach

Many years ago, Arizona took a different approach to charters than Mississippi. In Arizona, charters have a 15-year window rather than just a 5-year window to stay in business, as they do here. But most schools take far fewer than 15 years to prove their worth. And instead of the state stepping in to close poor-performing schools, parents do.

Over the past five years, more than 200 charters schools have opened in the Grand Canyon State. In the same five years, 100 other schools have closed. The average charter school that closes in Arizona is open just four years and has an average of 62 students in its final year. Parents don’t wait for the state to say if a charter is or isn’t meeting government benchmarks. They make a determination themselves. The charter sector grows according to demand, not top-down controls, ensuring that parents can make decisions about their child’s education without delay, rather than waiting for years to have a school or seat open up. Families also have many schools to choose from if one is not the right fit.

The data shows us that choice produces better student outcomes than tight government regulations.

In 2017, National Assessment of Education Progress, or NAEP, scores showed Arizona charters again performing as high as or better than traditionally top-performing states like Massachusetts, Minnesota, and New Jersey. Arizona did this while spending half of what those states spend and educating a high-minority student population.

Schools like Jackson Academy, Jackson Prep, St. Andrew’s, St Joe’s, MRA, Hartfield, and others compete for students every day. They sell themselves on why consumers, parents, should send their children to their school. And parents make decisions on where to enroll their children based on a host of reasons, ranging from academics to athletics, from values to extracurricular activities. This has created a robust private school market in the area. Why shouldn’t public schools of choice work similarly?

We’re glad leaders in Mississippi are working to create more public education options for those who want them. But the slow pace of opening charters, and the limitations on where they can be located or who can attend, is not leading to a responsive charter marketplace anytime soon. In these early stages of development, Mississippi has the opportunity to learn from other states and decide if parent demand and satisfaction should play a greater role in the charter approval process.

After all, what’s working for Arizona just might work here too.

This column appeared in The Northside Sun on September 20, 2018.

Men make more money than woman for numerous reasons. But it is not because of discrimination.

June O’Neill, an economics professor and former Congressional Budget Office director, has researched this issue and concluded that: “The gender gap largely stems from choices made by women and men concerning the amount of time and energy devoted to a career, as reflected in years of work experience, utilization of part-time work, and other workplace and job characteristics.”

Familial roles – such as who stays home with the kids when they are sick – tend to play a larger role in determining wages than does gender. As a result of such roles – most kids want mom to be the one to stay home – women often earn less than men. But in today’s labor market, gender discrimination is not the reason why.

- “Over 60 percent of all bachelor’s degrees are awarded to women.

- “More women than men continue to graduate school and more doctorates are awarded to women.

- “Women now comprise just over half of those employed in management, professional, and related occupations.”

Indeed, a recent Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) report finds that “women working 35-39 hours per week last year earned 107% of men’s earnings for those weekly hours, i.e., there was a 7% gender earnings gap in favor of female workers.”

As the gender pay gap is being debunked nationwide, some in Mississippi are clamoring for a state law to address an issue that is no longer an issue.

But Mississippi, like every other state, must abide by federal wage and hour laws. These laws, among other things, prohibit discrimination based on gender. An employer in Mississippi cannot discriminate against women just because we don’t have a state law prohibiting it.

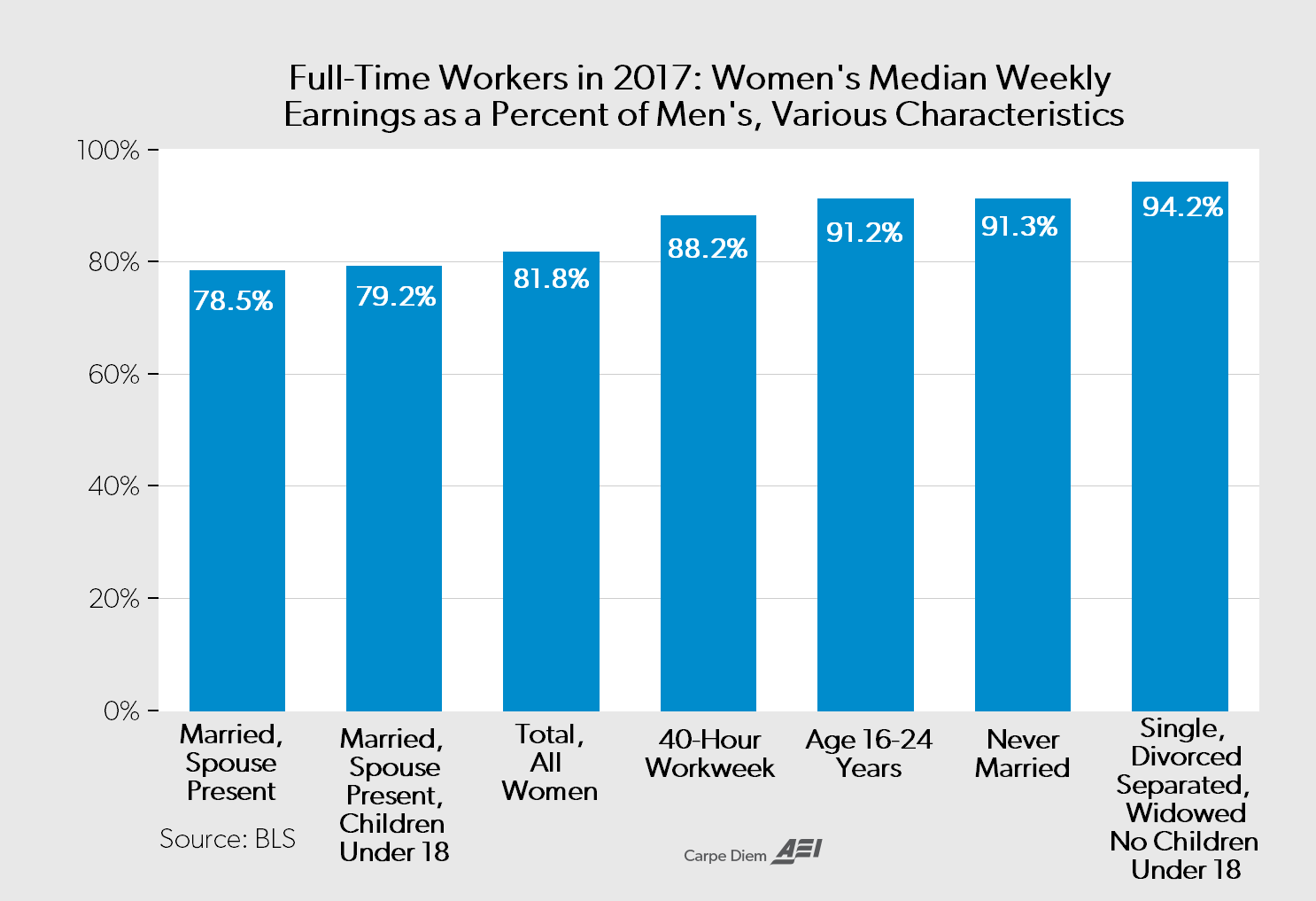

When controlling for hours worked and lifestyle choices, such as marriage, we get a clearer picture of earnings by gender.

Men work more hours than women

A review of data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows:

- 25.1 percent of men working full-time worked 41 or more hours per week, compared to only 14.3 percent of women. 5.8 percent of men worked 60 hours per week or more, compared to only 2.5 percent of women.

- 10.9 percent of women who worked full-time worked between 35 and 39 hours per week, compared to only 4.3 percent of men who did so.

- An estimation shows the average full-time man worked 43.2 hours per week compared to 41.5 hours for women, or 85 more hours a year.

Marital status also affects the earnings of women, as does many other factors.

- Single women who have never been married earn 91.3 percent of men’s earning, representing a gender gap of only 8.7 percent, eliminating more than half of the raw earnings gap.

- Full time women who are not married with no children under 18 earn 94.2 percent of men’s earnings, representing a gender gap of 5.8 percent, eliminating two-thirds of the raw gender gap.

- But married women, with and without children, earn 79.2 percent and 78.5 percent, respectively, of what similar men earn.

As we see, being married has a negative impact on the earnings of women. But one could also presume that that is a personal choice, and women may place greater value on flexibility, commute time, child care, and other factors important to those with children at home.

In the end, there is no gender wage gap when we compare apples to apples: doing exactly the same work while working the exact same number of hours in the same occupation.

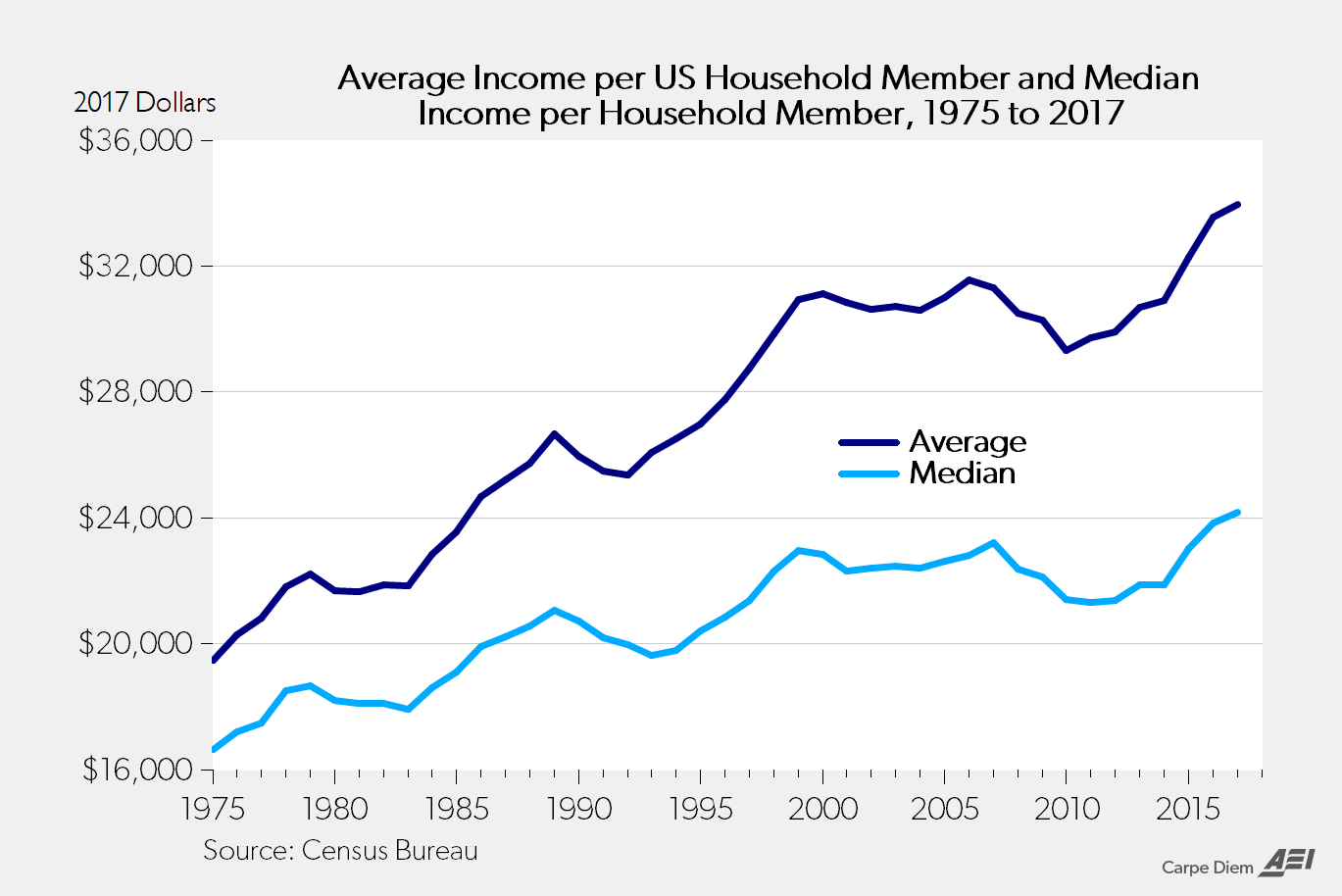

Incomes in America rose to a new high in 2017 despite the constant talking points that the economy is only working for a few.

According to the latest data from the Census Bureau, American households have made their way solidly out of the recession and incomes continue to rise. And the report includes other significant data: Income inequality is more of a talking point than a reality and middle-income earners are actually moving up the economic ladder, not down. All while, the price of consumer goods continues to go down.

Median household income

Median household income last year was $61,372, an increase of 1.8 percent from the previous year in today’s dollars. This is the fifth consecutive annual increase after a half-decade of declines following the Great Recession. The last period of four consecutive gains was in the late 1990s.

Compared to 1975, annual incomes per household member, again in today’s dollars, are up more than $12,000. That means each America has an additional $1,000 in additional income per month than they did forty years ago.

Income inequality

One of the most common refrains we hear in politics today is about the rising income gap. It has spurred a new belief in socialism, and propelled the candidacy of Democratic-Socialist Bernie Sanders in 2016. Other have since followed in his footsteps.

President Barack Obama once called it the “defining challenge of our time.”

Two data points show that the shares of total income earned by the top 20 percent and the top 5 percent are relatively static. Meaning, the rich aren’t getting richer at the expense of everyone else. Over the past two decades, the income shares of the top 20 percent and the top 5 percent have remained stable at 49-51 percent and 21-22 percent, respectively.

As the chart shows, these percentages are relatively static during this time.

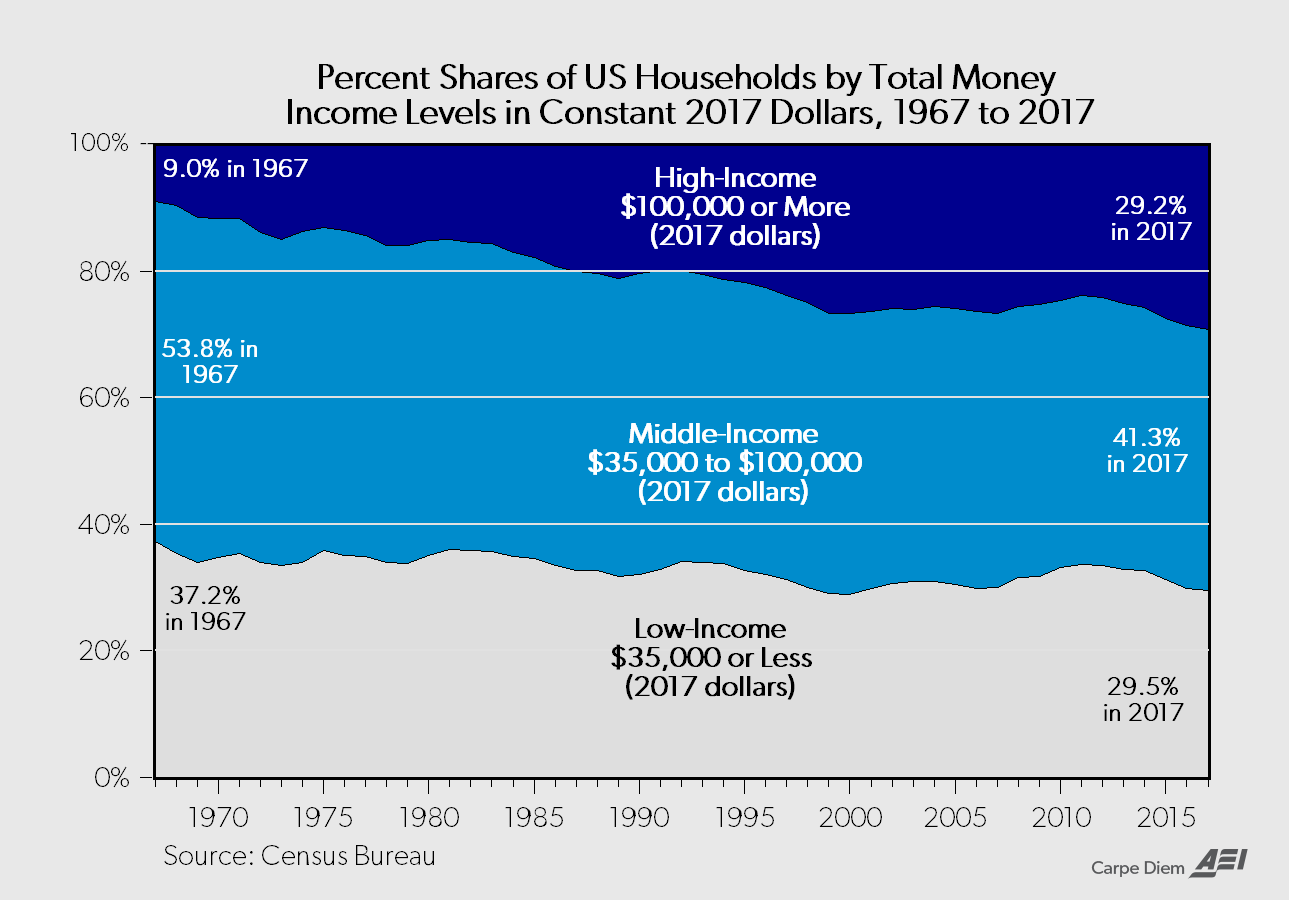

The middle class

Another common refrain is the disappearing middle class. After all, in 1967 53.8 percent of the population was considered middle income, those who make between $35,000-$100,000 (in today’s dollars). But the middle class is getting smaller because they are moving up to higher income groups. That is a good thing.

The size of high-income earners, those who make $100,000 or more is 29.2 percent. Forty years ago, only 9 percent fit in this category. That represents a growth of high earners of 224 percent. Meanwhile the share of low-income earners, those who make $35,000 or less, has fallen from 37.2 percent in 1967 to 29.5 percent today. A decrease of 20 percent.

Price of consumer goods

Usually involved in this discussion is the fact that everything seems much more expensive than it was a few decades ago. A lot of this is nostalgia, but there are some items that are indeed more expensive, significantly more so in many cases. That primarily includes healthcare and higher education, two sectors of the economy that are heavily regulated and influenced by the government.

Housing, which is often negatively impacted (in terms of cost to the consumer) by local government regulations, has largely kept pace with inflation.

But most every day consumer goods, everything from cars and home furnishings to appliances and clothing, have become more affordable. What do these goods have in common? They are controlled by the free market, not the government.

For some, they may be struggling. They may not have bounced back from the recession or perhaps life choices put them in a less-than-desirable situation. But we know, when we move past the talking points and political campaigns, Americans have never been doing better. The middle class isn’t shrinking. It’s getting wealthier. Incomes are not growing apart. And every day purchases aren’t getting more expensive.

Thanks to capitalism and the free market.

Preliminary data shows that overall enrollment in Mississippi’s eight public universities and 15 community and junior colleges is down over the previous year.

Enrollment for the fall of 2018 stands at 80,592, compared to 81,378 last year.

Among Mississippi’s eight public universities, enrollment is up at Alcorn State, Mississippi State, Mississippi Valley State, and Southern Mississippi. Enrollment is down at the other four universities: Delta State, Jackson State, Mississippi University for Women, and Ole Miss.

Southern Miss enjoyed the largest growth, from 14,478 students to 14,743, an increase of 1.8 percent. Their freshman class grew from 1,903 students last year to 2,115 this year. Mississippi State grew by 1.5 percent, from 21,883 students to 22,201. State’s freshman class grew from 3,438 students to 3,599.

Ole Miss, including enrollment at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, has the largest enrollment in the state at 23,258. That is down 2.2 percent from last year when the system enrolled 23,780 students. This is the second consecutive year of a decline. Last year’s enrollment was down 1.9 percent. The freshman class at Ole Miss is down 6.5 percent, from 3,697 students to 3,455.

The biggest drop, however, was at Jackson State. Enrollment is down to 7,709 from 8,558 last year. This represents at 9.9 percent decrease.

Total student enrollment, Fall 2017 compared to Fall 2018

| Institution | 2017 | 2018 | Number change | % change |

| Alcorn State | 3,716 | 3,753 | 37 | 1% |

| Delta State | 3,789 | 3,784 | -5 | -0.1% |

| Jackson State | 8,558 | 7,709 | -849 | -9.9% |

| MSU | 21,883 | 22,201 | 318 | 1.5% |

| MUW | 2,789 | 2,738 | -51 | -1.8% |

| MVSU | 2,385 | 2,406 | 21 | 0.9% |

| Ole Miss | 23,780 | 23,258 | -522 | -2.2% |

| Southern | 14,478 | 14,743 | 265 | 1.8% |

| Totals | 81,378 | 80,592 | -786 | -1% |

Enrollment among Mississippi’s 15 junior and community colleges fell to 72,255, a decline of 0.8 percent from the previous year. Pearl River (2.6 percent), Southwest Mississippi (2.9 percent), Northeast Mississippi (2.9 percent), and Mississippi Delta (3.2 percent) were the largest gainers.

Coahoma (-5.2 percent), Northwest Mississippi (-5.8 percent), and Meridian (-6.3 percent) had the biggest drop percentage wise. Hinds, whose enrollment was flat, remains the largest school in the community college system at 11,833 students.

The city of Tupelo is in the process of drafting new regulations for food truck operators within the city limits.

According to the Daily Journal, city leaders hope to have an ordinance before the council in October. This has been in the works for some time now, with leaders talking about food truck regulations back in May.

At that time, Councilman Willie Jennings said, in proposing the regulations, “I just want to make sure the established businesses are protected.” Another councilman, Markel Whittington, said brick-and-mortar restaurants have requested food truck regulations. While he didn’t feel food trucks posed a ‘threat’ to those restaurants, he believed it was appropriate for government to act ‘on behalf of select business interests.’

“I think we have to protect some of our taxpayers and high employers,” he said.

The proposed ordinance would likely prohibit food trucks from operating on public property along major thoroughfares. Major thoroughfares include virtually all of Main and Gloster streets, two of the most prominent retail areas in the city.

And they also happen to be where most food trucks are currently located.

When Tupelo leaders began discussing food truck regulations, Mississippi Justice Institute, the legal arm of Mississippi Center for Public Policy, sent a letter to the city warning of litigation if these regulations passed.

“The very regulation Tupelo is discussing—a regulation about how close a food truck should be to a restaurant—was found to be unenforceable just this past December in Baltimore. Food truck regulations around the country have been challenged over and over in court, from Louisville, to San Antonio, to Chicago, and many places in between. Cities ultimately realize that these kinds of cases are very hard to defend,” the letter said.

More recently, the city of Carolina Beach, North Carolina repealed it’s prohibition on out-of-town food trucks from serving the city after a lawsuit was filed by the Institute of Justice. Under the law that has since been scrapped, only brick-and-mortar restaurants that have been in business for more than one year could run a food truck.

“It is a shame that it took a lawsuit to convince the town to repeal such an obviously unconstitutional law,” Justin Pearson, senior attorney at IJ said. “I’m hopeful that this vote will signal the end to the town’s attempt to use the power of government to favor a handful of established businesses over the region’s entrepreneurs.”

Food trucks are already regulated like brick-and-mortar establishments. They must already obtain a license from the city and the state, along with a health permit from the Department of Health.