As a candidate for insurance commissioner in 2007, then-State Sen. Mike Chaney floated the idea of making the position he was running for appointed.

He went on to win election that year and is the odds-on favorite to win a fourth term in a couple months. The legislature never considered making this position appointed. And likely never will. Because we love electing people. Even if we don’t really know what the office does, who is running, or what other states are doing.

Today, Mississippi is one of 11 states that elect insurance commissioners. That’s not the only anomaly.

The agriculture commissioner is elected in 12 states, mostly in the Southeast. Mississippi has three public service commissioners, divided among the northern, central, and southern regions of the state. We are one of 11 states that elects public service commissioners. That’s better than our other regionally elected office – transportation commissioner. We are the only state that still elects transportation commissioners.

We find a little more election popularity among other statewide offices. The auditor is elected in 24 states, so close to half. The secretary of state is elected in 35 states and the treasurer is elected in 36 states, so we can at least claim to be with the majority of other states for those two positions.

And every judge on the supreme court and the court of appeals is elected. Not to mention many of the county and municipal posts that could easily be appointed.

Could we ever see an elected position become appointed?

The lack of interest in appointing a position like the insurance commissioner probably answers that question. But we have seen minor change here and there.

We use to elect the state superintendent of education. And four years ago, the legislature switched to appointed school superintendents for every school district. At the time, we were one of the last three states to make the move.

Odds are we won’t be seeing much change. People like electing officials even if the office is simply a regulatory post where the focus should be on the most qualified individual, not the one who is best at receiving the most votes.

As Ole Miss gets ready for their first football game of the season on Saturday, university officials are marching forward with plans to remove the Confederate statue near the entrance to campus.

Interim Chancellor Larry Sparks, who holds the position while the Institutions for Higher Learning searches for the next Ole Miss chancellor, said the school intends to move the statue to the Confederate cemetery, near the old Tad Smith Coliseum.

The university has submitted plans to the Mississippi Department of Archives and History and the IHL. Once the university receives the green light, the school hopes to have the monument relocated within 90 days.

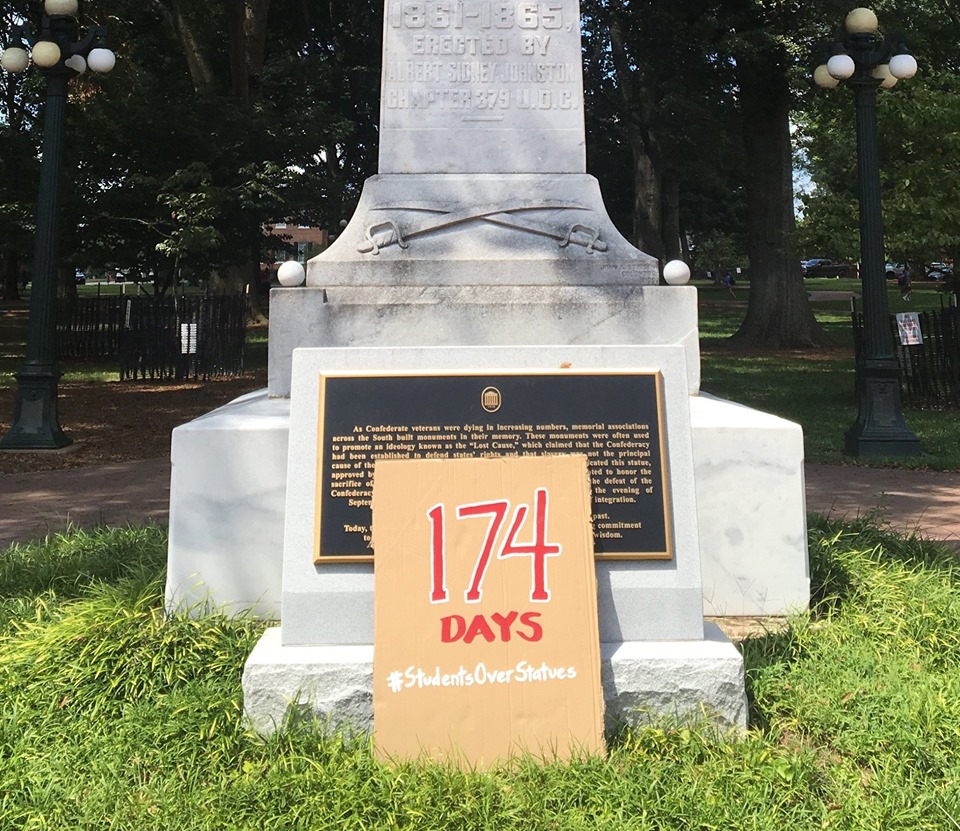

The push for the statues removal began to get increased attention last fall when a group known as the Students Against Social Injustice staged a protest and issued demands of the administration, something that is now common practice among left-wing campus organizations.

According to SASI, the university must remove the Confederate statue from campus and speech codes must be implemented to “protect students from the racist violence we experience on campus.” And, the next chancellor “must” meet with this group to discuss their demands.

Last spring, the Associated Student Body voted to relocate the statue, as did three other governing bodies.

SASI, which includes students and liberal professors, has since been putting their own markers on the statue marking the number of days since the ASB vote.

Before the SASI push to move the statue, the university placed plaques on various locations on the campus, including the statue. This was done in early 2018 as part of a years-long process. These plaques are designed to "contextualize" names or objects on campus.

Only four states have seen a higher percentage of people leave the federal food stamps program over the past year than Mississippi.

In May 2018, 498,490 Mississippians were on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP. By April of this year, that number had declined to 443,868 participants. This represents a drop of 11 percent over the last 11 months that data is available.

These numbers coincide with recent job numbers that show more people in Mississippi are working. Over the past 12 months, Mississippi experienced a job growth rate of 1.7 percent, good enough for 17th nationally and fifth in the SEC footprint.

The states that saw a larger percentage drop from the SNAP rolls were Georgia (-12.6 percent), New Hampshire (-12.4 percent), Wyoming (-11.4 percent), and Kentucky (-11.3 percent).

Nationally, SNAP participation has steadily declined since the recession and over the past year it dropped by another 6.5 percent representing a decrease of about 2.5 million people.

The percent of Mississippians receiving food stamps dropped a full two percent over the last year. In May 2018, a little less than 17 percent of the state received food stamps. Today that number is just under 15 percent.

Percent of residents using SNAP among neighboring states

| State | SNAP percentage (2019) | SNAP percentage (2018) |

| Alabama | 14.6% | 15.4% |

| Arkansas | 11.5% | 12% |

| Louisiana | 17% | 18.4% |

| Mississippi | 14.9% | 16.7% |

| Tennessee | 13.1% | 13.9% |

Contrary to what you will hear from many candidates running for office, Mississippi is spending more taxpayer funds to educate a decreasing amount of K-12 students, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

In 2014, local, state and federal funding added up to $4.467 billion or about $9,068 per each of the state’s 492,586 students in public schools.

Fast forward to 2017, taxpayers spent a total of $4.75 billion on K-12 in Mississippi from local, state and federal sources. That added up to $10,092 apiece to educate 470,668 students enrolled in public schools.

Those add up to 7.57 percent and 6.8 percent increases, respectively, in state and local spending compared with 2014.

During that same period, enrollment in Mississippi public schools decreased by 4.5 percent.

Mississippi ranks 41st in per unadjusted, total per-pupil spending among the 50 states and the District of Columbia.

South Carolina (35th) is the second highest ranking Southeastern state in per-student spending, along with Arkansas (36th), Georgia (40th), Alabama (42nd) and Florida (45th).

The District of Columbia spends the most per student nationally, an astronomical $27,696. According to a 2018 audit report, students are allowed to pass courses despite excessive unexcused absences and there is a culture of passing and graduating students who didn’t meet standards.

| Area | Total | Federal sources | State sources | Local sources | Enrollment | Per pupil spending |

| District of Columbia | $ 1,342,220 | $ 134,959 | $ - | $ 1,207,261 | 48,462 | $ 27,696 |

| New York | $ 61,100,409 | $ 3,347,393 | $ 24,830,862 | $ 32,922,154 | 2,598,181 | $ 23,517 |

| Connecticut | $ 10,516,316 | $ 420,593 | $ 4,141,590 | $ 5,954,133 | 496,074 | $ 21,199 |

| New Jersey | $ 27,408,345 | $ 1,142,878 | $ 11,047,025 | $ 15,218,442 | 1,360,686 | $ 20,143 |

| Alaska | $ 2,663,488 | $ 309,525 | $ 1,824,373 | $ 529,590 | 132,737 | $ 20,066 |

| Vermont | $ 1,672,580 | $ 102,434 | $ 1,495,453 | $ 74,693 | 87,630 | $ 19,087 |

| Wyoming | $ 1,771,027 | $ 112,709 | $ 965,213 | $ 693,105 | 93,925 | $ 18,856 |

| Massachusetts | $ 16,474,364 | $ 791,029 | $ 6,587,492 | $ 9,095,843 | 919,967 | $ 17,908 |

| Pennsylvania | $ 27,647,475 | $ 1,812,609 | $ 10,272,392 | $ 15,562,474 | 1,576,334 | $ 17,539 |

| Rhode Island | $ 2,289,429 | $ 186,551 | $ 867,512 | $ 1,235,366 | 133,230 | $ 17,184 |

| New Hampshire | $ 2,943,450 | $ 161,989 | $ 1,003,995 | $ 1,777,466 | 178,801 | $ 16,462 |

| Maryland | $ 13,978,426 | $ 816,033 | $ 6,186,736 | $ 6,975,657 | 885,820 | $ 15,780 |

| Delaware | $ 1,904,776 | $ 133,055 | $ 1,137,764 | $ 633,957 | 121,542 | $ 15,672 |

| Illinois | $ 30,407,109 | $ 2,301,827 | $ 11,163,462 | $ 16,941,820 | 2,016,729 | $ 15,077 |

| Hawaii | $ 2,696,766 | $ 286,988 | $ 2,354,601 | $ 55,177 | 181,550 | $ 14,854 |

| Maine | $ 2,609,930 | $ 182,961 | $ 1,032,280 | $ 1,394,689 | 178,216 | $ 14,645 |

| Ohio | $ 22,423,472 | $ 1,692,769 | $ 9,492,461 | $ 11,238,242 | 1,590,877 | $ 14,095 |

| North Dakota | $ 1,530,158 | $ 155,894 | $ 901,032 | $ 473,232 | 109,667 | $ 13,953 |

| Minnesota | $ 11,017,479 | $ 630,445 | $ 7,603,409 | $ 2,783,625 | 818,803 | $ 13,456 |

| Michigan | $ 17,529,062 | $ 1,563,397 | $ 10,073,758 | $ 5,891,907 | 1,327,204 | $ 13,208 |

| Wisconsin | $ 11,001,272 | $ 830,568 | $ 5,709,579 | $ 4,461,125 | 855,924 | $ 12,853 |

| West Virginia. | $ 3,502,513 | $ 351,957 | $ 2,033,948 | $ 1,116,608 | 273,170 | $ 12,822 |

| Louisiana | $ 8,323,024 | $ 1,272,004 | $ 3,455,315 | $ 3,595,705 | 656,257 | $ 12,683 |

| Nebraska | $ 3,926,537 | $ 318,179 | $ 1,283,012 | $ 2,325,346 | 318,853 | $ 12,315 |

| Iowa | $ 6,194,941 | $ 455,586 | $ 3,247,115 | $ 2,492,240 | 509,831 | $ 12,151 |

| Indiana | $ 12,149,675 | $ 933,891 | $ 7,632,238 | $ 3,583,546 | 1,002,135 | $ 12,124 |

| Washington | $ 12,943,921 | $ 1,030,232 | $ 7,833,024 | $ 4,080,665 | 1,098,187 | $ 11,787 |

| Montana | $ 1,712,493 | $ 201,528 | $ 822,788 | $ 688,177 | 145,559 | $ 11,765 |

| Kansas | $ 5,812,358 | $ 419,415 | $ 3,265,012 | $ 2,127,931 | 494,062 | $ 11,764 |

| Virginia | $ 15,083,311 | $ 1,009,659 | $ 5,994,897 | $ 8,078,755 | 1,286,711 | $ 11,722 |

| Missouri | $ 10,163,998 | $ 895,743 | $ 4,267,069 | $ 5,001,186 | 887,503 | $ 11,452 |

| Oregon | $ 6,573,206 | $ 521,463 | $ 3,393,147 | $ 2,658,596 | 576,911 | $ 11,394 |

| California | $ 69,857,908 | $ 7,415,061 | $ 38,410,554 | $ 24,032,293 | 6,195,344 | $ 11,276 |

| New Mexico | $ 3,601,387 | $ 466,320 | $ 2,505,492 | $ 629,575 | 319,526 | $ 11,271 |

| South Carolina | $ 8,405,682 | $ 812,536 | $ 3,902,923 | $ 3,690,223 | 747,868 | $ 11,240 |

| Arkansas | $ 5,175,529 | $ 552,738 | $ 4,006,889 | $ 615,902 | 478,996 | $ 10,805 |

| Kentucky | $ 7,228,770 | $ 825,742 | $ 3,966,872 | $ 2,436,156 | 683,864 | $ 10,570 |

| Texas | $ 52,609,018 | $ 5,643,178 | $ 20,510,815 | $ 26,455,025 | 5,087,263 | $ 10,341 |

| Colorado | $ 9,117,534 | $ 681,230 | $ 3,961,719 | $ 4,474,585 | 885,492 | $ 10,297 |

| Georgia | $ 17,817,933 | $ 1,804,212 | $ 7,837,335 | $ 8,176,386 | 1,732,691 | $ 10,283 |

| Mississippi | $ 4,750,000 | $ 664,697 | $ 2,243,098 | $ 1,559,519 | 470,668 | $ 10,092 |

| Alabama | $ 7,355,547 | $ 794,090 | $ 4,031,547 | $ 2,529,910 | 744,930 | $ 9,874 |

| South Dakota | $ 1,342,877 | $ 186,216 | $ 413,544 | $ 743,117 | 136,117 | $ 9,866 |

| Nevada | $ 4,201,457 | $ 381,596 | $ 2,651,854 | $ 1,168,007 | 442,931 | $ 9,486 |

| Florida | $ 26,072,680 | $ 3,112,027 | $ 10,460,928 | $ 12,499,725 | 2,801,945 | $ 9,305 |

| North Carolina | $ 13,462,754 | $ 1,529,624 | $ 7,849,343 | $ 4,083,787 | 1,457,600 | $ 9,236 |

| Tennessee | $ 9,215,027 | $ 1,095,377 | $ 4,315,952 | $ 3,803,698 | 1,000,662 | $ 9,209 |

| Oklahoma | $ 6,032,331 | $ 690,122 | $ 2,983,860 | $ 2,358,349 | 669,462 | $ 9,011 |

| Arizona | $ 8,293,591 | $ 1,102,980 | $ 3,182,285 | $ 4,008,326 | 936,147 | $ 8,859 |

| Utah | $ 4,400,351 | $ 385,210 | $ 2,363,055 | $ 1,652,086 | 588,119 | $ 7,482 |

| Idaho | $ 2,084,312 | $ 232,593 | $ 1,319,582 | $ 532,137 | 279,026 | $ 7,470 |

The highest ranking Southeastern state is Louisiana, which spends $12,683 per pupil and is ranked 23rd.

The Pelican State uses a similar K-12 education funding formula to the Mississippi Adequate Education Program, the Minimum Foundation Program, to divide up state funding among school districts.

The difference between the two states is that the MFP amount is constitutionally mandated by the Louisiana state constitution, leaving the Louisiana legislature with precious little maneuvering room in the budget during tough economic times.

The MAEP, thanks to a 2017 decision by the state Supreme Court, is not a binding funding amount for the legislature.

In fiscal 2020, the MAEP formula amount totaled $2.477 billion and the legislature appropriated $2.246 billion, a difference of $231,505,356.

In 2017, state ($2.413 billion or 50.8 percent), local ($1.666 billion or 35.1 percent) and $671 million for federal spending (14.1 percent) composed the taxpayer outlay on K-12 education in Mississippi.

For Mississippi to equal Louisiana in per-pupil spending, the state would have to spend more than $619 million more in state K-12 spending and more than $428 million in local spending.

According to the Census data, Louisiana spends more on salaries and benefits (80.98 percent versus 79.4 percent in Mississippi) and a slightly smaller percentage — 55.76 percent versus 56.68 percent for the Magnolia State — on instruction related outlays.

Louisiana (38.79 percent) spends more on support services — defined as school and district office administration and instructional staff support — than Mississippi (36.88 percent).

No sane person would argue that Mississippi is not a place with a strong sense of tradition. Mississippi literally drips with the fine traditions of family loyalty, religious liberty, community charity, and the value of life.

Some would also refer to a place like this as being “conservative.” From a social perspective, I would agree. However, when we look at the Magnolia State through the lens of public policy and political philosophy, the word “conservative” does not apply.

Though Mississippi has been governed mostly by Republicans, that does not make it a conservative state. We can’t measure our conservatism by our political affiliation or social conscience alone.

We must look deeper into the meaning of conservatism. Being conservative in America means, by definition, you favor constitutionally limited government, the mechanism of free markets, and the personal liberty and responsibility we have as individuals.

A conservative is willing to stand up to encroaching power of all forms of government (city, county, state and federal), to the growing corporatism that seeks to govern us from the boardroom, and to the menace to our society that is a progressive culture. Being a conservative means holding your representatives to account for fiscal discipline, for reducing our regulatory burdens, and for keeping our taxes low so that every Mississippian keeps more of his or her own money and freedom.

The recent gubernatorial race was particularly instructive. A candidate for governor, who constantly referred to himself as a conservative, ran on a plank of raising the gas tax and expanding Medicaid.

Distinguished, non-partisan organizations all across the country have provided empirical evidence and shared instructive data on the imprudence of states expanding Medicaid, like this one from my counterpart at the conservative Pelican Institute in Louisiana. The conservative and libertarian think tanks all over the nation are opposed to the expansion of Medicaid by states. Yet, a candidate for the highest office in the state supported the policy of expansion while referring to himself as a conservative.

That’s a head-scratcher for me.

On the issue of the gas tax, the current governor called a special session last year and passed what was then called “landmark” legislation to address the infrastructure issues of our state’s highways and bridges. Through a combination of an internet sales tax, sports gambling taxes, lottery revenues, and bonding, it was announced that government found a way to commit over a billion dollars to infrastructure projects over the next five years. Full-page ads were taken out by trade groups and chamber of commerce-type organizations to “recognize the historic achievement.”

Less than a year later, a candidate for governor was claiming we needed to “do something to address our crumbling roads and bridges.” This is despite the fact that our state roads and bridges are ranked as the 11th best in the nation by Reason Magazine in their 23rd Annual Highway Report. I’ve driven most of the roads in the Southeast; our state roads are just fine. The crumbling streets, roads, and bridges are found mostly in a few of the cities and counties of Mississippi. Jackson/Hinds being the worst example and the one most of the political class has to contend with on a daily basis. As a Jackson resident, I agree. Our roads are among the worst in the country, but that’s not a state issue. That issue is one of municipal funding and management. We provided an analysis on this earlier this year.

If we want to succeed and get ourselves out of last place, it’s not going to happen by deepening our dependence on government solutions. Every tax is a decision to give more power and responsibility to the state. There is no evidence that government will spend that money more effectively than we would spend it ourselves.

We already have far too many Mississippians who seek to petition government to solve problems we’re better off solving through the private institutions of free enterprise, churches, nonprofits, communities, and families. Too many individuals and companies are looking to the government for a contract, a job, a partner, or protection from competition.

When we allow government to wield this much power, we weaken the free market. We create a disincentive to the formation and deployment of capital. We thwart the opportunity for all Mississippians to prosper. What’s more, such reliance on government ensures only those with power have significant influence on Mississippi, including determining who represents us in the legislative and executive branches of our government.

What makes a “conservative” is not a party or allegiance to a particular leader or political campaign, but the power of ideas. As conservatives, our ideas are based on bedrock values and fundamental truths. Freedom is a policy that works. A limited and restrained government is the essence of our system. And the principle of ordered liberty holds it all together.

Our goal at the Mississippi Center for Public Policy is to play a leadership role in building a Mississippi where individual liberty, opportunity, and responsibility reign because government is limited. We believe this is the only way nations, states, and cities have ever enjoyed durable prosperity.

If we remain committed to these ideas and work hard to convince others of their value, we can all experience a magnolia renaissance. And we can say conservatism made it possible. Real conservatism. The kind of which Bill Buckley, Ronald Reagan, and Milton Friedman spoke. The kind where we are free to pursue our individual liberty and speak our minds. The kind where we encourage people to take action and take risks in pursuit of their happiness. The kind where we take personal responsibility for our futures and stop looking for government to solve all of our problems.

There is an important role for government but it must be limited. Government functions best when it is closest to the people and when it is open and transparent.

Although our national government continues to grow into an unwieldy and bureaucratic swamp, our country is still federalist. We are a collection of semi-sovereign states. Federalism is a conservative idea. As Reagan stated in his first inaugural address, “The federal government did not create the states; the states created the federal government.”

Thanks to our founding fathers, the real political and policy power is supposed to belong to the states. Therefore, we hold the key to our own future. Our future does not belong to the bureaucrats and politicians in Washington.

Let’s remember who we are...and vote accordingly.

In this edition of Unlicensed, we talk about Tuesday's runoff, who won, who lost, and where we go from here.

And will Bill Waller endorse the Republican nominee or the Democratic candidate that he is seemingly more closely aligned with? Or will he just stay on the sidelines?

Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves defeated former Supreme Court Justice Bill Waller 54-46 in yesterday’s runoff for the Republican nomination for governor.

Reeves advances to the general election where he will meet Democrat Attorney General Jim Hood.

Republicans also chose their attorney general nominee. State Treasurer Lynn Fitch defeated attorney Andy Taggart 52-48. Fitch will face Democrat Jennifer Collins in November as Republicans look to finally capture the one statewide office they don’t hold.

Republicans in the northern district chose a nominee for transportation commissioner. John Caldwell defeated Geoffrey Yoste 57-43. Caldwell will meet Democrat Joe Grist in the general election.

And Jackson Councilman De’Keither Stamps will be the Democratic nominee for Public Service Commissioner in the central district. Stamps will face Republican Brent Bailey in November. Bailey was the Republican nominee four years ago as well, losing to Democrat Cecil Brown.

For the legislature, five Republican incumbents and two Democratic incumbents lost their bids for re-election. As of 8:30 a.m. Wednesday morning, two races – Senate District 3 and Senate District 50 – have yet to be called.

| District | Party | Name | % | Name | % |

| SD1 | R | Michael McLendon | 52 | Chris Massey* | 48 |

| SD3 | R | Kathy Chism | 51 | Kevin Walls | 49 |

| SD8 | D | Kegan Coleman | 62 | Kathryn York | 38 |

| SD8 | R | Stephen Griffin | 52 | Ben Suber | 48 |

| SD10 | D | Andre De’Berry | 56 | Michael Cathey | 44 |

| SD13 | D | Sarita Simmons | 66 | John Alexander | 34 |

| SD22 | D | Joseph Thomas | 61 | Ruffin Smith | 39 |

| SD37 | R | Melanie Sojourner | 55 | Morgan Poore | 45 |

| SD51 | R | Jeremy England | 50 | Gary Lennep | 50 |

| HD10 | R | Brady Williamson | 58 | Kelly Morris | 42 |

| HD63 | D | Stephanie Foster | 63 | Deborah Dixon* | 37 |

| HD70 | D | William Brown | 53 | Kathy Sykes* | 47 |

| HD87 | R | William Andrews | 51 | Joseph Tubb | 49 |

| HD88 | R | Ramona Blackledge | 57 | Gary Staples* | 43 |

| HD95 | R | Jay McKnight | 59 | Patricia Willis* | 41 |

| HD105 | R | Dale Goodin | 56 | Roun McNeal* | 44 |

| HD106 | R | Jansen Owen | 61 | John Glen Corley* | 39 |

| HD114 | R | Jeffrey Guice* | 54 | Kenneth Fountain | 46 |

Races in italics have yet to be called.

Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves defeated former Supreme Court Justice Bill Waller in the runoff for the Republican nomination for governor. Reeves advances to face Democrat Attorney General Jim Hood in the November general election.

Reeves maintained a steady lead throughout the night as results began to trickle in. The race was called shortly before 9 p.m.

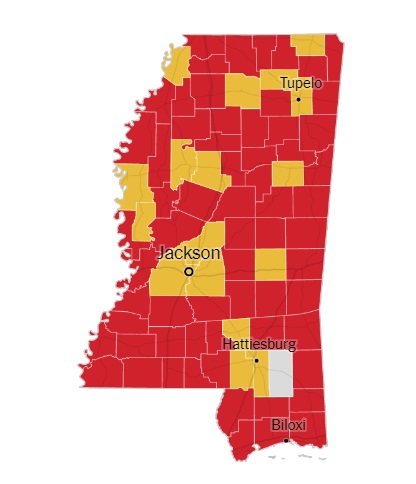

As county totals began to appear, the board looked eerily similar to three weeks ago. A huge chunk of votes for Waller in Hinds, Madison, and Rankin counties, while Reeves performed well virtually everywhere else in the state.

Waller made some new inroads, particularly Northeast Mississippi, but it wasn't nearly enough to slow down Reeves in Republican primary strongholds outside the metro area.

Map: Counties won by each candidate

This includes the population centers that are furthest north and south in the state.

Once again, Reeves was simply dominant in the lower six counties, most notably, the three Coast counties. Reeves won 66 percent of the vote in Harrison county, 69 percent in Hancock county, and 71 percent in Jackson county. South Mississippi again was able to provide the numbers needed to counteract Waller's strength in the metro area.

And Reeves notched a victory in Desoto county. It was carried by State Rep. Robert Foster, who represents a House district in Desoto county, three weeks ago. Foster proceeded to endorse Waller, but Reeves still won 54 percent of the vote in the county.

Also, as of 9:30 p.m., state Treasurer Lynn Fitch was maintaining a small lead over attorney Andy Taggart in the race for the Republican nomination for attorney general. With 90 percent in, Fitch was leading 51.5- 48.5 though the race has yet to be called.

Stay tuned. We will have more election coverage on Wednesday.

The small town of Walls in DeSoto county, population 986, leads the state in the amount of its budget coming from fines and forfeitures.

According to the study by Governing magazine, the town sourced 26.53 percent of its budget from fines and forfeitures in 2017. That adds up to $249 of fines per resident.

Data from the state auditor’s office shows this number didn’t occur in isolation. Walls had 25.7 percent of its budget originating from fines and forfeitures in 2015 and 32.2 percent in 2014.

In 2017, the town had revenues of $898,808 and $238,476 came from fines and forfeitures.

Numbers from 2016 were not available.

| City | Year | General fund fines and forfeitures | Total general revenues | Share of general revenues | Fines and forfeitures per adult resident | Population |

| Walls | 2017 | $ 238,476 | $ 898,808 | 26.53% | $ 249 | 958 |

| Guntown | 2016 | $ 108,553 | $ 790,844 | 13.73% | $ 61 | 1,780 |

| Bruce | 2017 | $ 196,744 | $ 1,722,886 | 11.42% | $ 138 | 1,426 |

| Decatur | 2017 | $ 133,442 | $ 767,961 | 17.38% | $ 83 | 1,608 |

| Laurel | 2018 | $ 1,614,160 | $ 17,073,552 | 9.45% | $ 126 | 12,811 |

| Ellisville | 2017 | $ 476,254 | $ 3,189,997 | 14.93% | $ 131 | 3,636 |

| Mendenhall | 2015 | $ 173,357 | $ 1,511,996 | 11.47% | $ 90 | 1,926 |

| Florence | 2017 | $ 355,079 | $ 2,558,194 | 13.88% | $ 120 | 2,959 |

| Raymond | 2017 | $ 120,076 | $ 736,103 | 16.31% | $ 62 | 1,937 |

| Flowood | 2018 | $ 981,949 | $ 20,433,623 | 4.81% | $ 196 | 5,010 |

The Rankin county city of Flowood was second, with $196 of fines and forfeitures per each of its 7,823 residents. The city had revenues of $20.4 million in 2018 and $981,949 came from fines and forfeitures.

Going by percentage of a city or town’s budget, the town of Decatur in Newton Ccunty was second to Walls, with $133,442 of its revenues in 2017 ($767,961) coming from fines and forfeitures.

Mississippi’s numbers were better than most, with only nine jurisdictions receiving 10 percent or more of their revenue from fines and forfeitures. Alabama had nine, Tennessee had 18 and Arkansas had 44 jurisdictions with 10 percent or more of revenue originating from fines and forfeitures.

Louisiana had 70 municipalities and counties in the 10 percent category and had 25 areas receiving 50 percent or more of their budgets from fines and forfeitures.

Georgia had the most nationally, with 92 receiving 10 percent or more of revenue from fines and forfeitures. The Peach State had 13 jurisdictions that received more than 50 percent of their revenue from fines and forfeitures.

Texas was second with 90 jurisdictions in the 10 percent or greater cohort.

According to the study, fines and forfeitures account for more than 10 percent of general fund revenues for nearly 600 jurisdictions surveyed by Governing magazine. In 284 of those, fines and forfeitures were 20 percent or more of revenue.

One hundred twenty four jurisdictions had fine revenues exceeding $500 per capita.