Department of Public Safety Commissioner Marshall Fisher attempted to link the cultivation of hemp and laboratory-created synthetic cannabinoids (often known as spice) laced with the opioid fentanyl in testimony Monday.

Fisher made the remarks in reference to the lack of quality control over cannabidiol (CBD oil) products, which is being researched as a possible seizure-arresting medication at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in addition to use in dietary supplements.

“There’s no vetting process that I’m aware of whether these (CBD) products are actually perused by anybody before they’re put out there,” Fisher said. “There’s story after story, anecdotal stories out here on the streets and in the papers about the spice and the deaths.

“There’s no quality control with people selling this as narcotics. You have bodies all over this country, people in funeral homes and cemeteries who’ve died of fentanyl overdoses because of fentanyl being mixed with other drugs.”

Listen to audio of Fisher

He was speaking at the first Hemp Cultivation Task Force meeting at the state Capitol. The task force was created by House Bill 1547 to study the potential for cultivation of hemp, how to regulate it and its possible effects on the state’s economy. A report of recommendations issued by the task force is due to Gov. Phil Bryant by December 6.

Task Force chairman Andy Gipson, the state’s agriculture commissioner, said that he wants the report to be well thought out and evidence based. He also said the group will consider the challenges and opportunities that hemp can present the state.

Hemp is the same Cannabis sativa plant that is marijuana, but the difference is the amount of the psychoactive substance Tetrahydrocannabinol, also known as THC. According to the farm bill passed by Congress in 2018, hemp is defined as strains of the cannabis plant with a THC level of 0.3 percent or less.

Don’t expect any discussion of legalized marijuana at the task force meetings, because Gipson said the task force won’t be engaging in any other issues other than those related to hemp cultivation.

Fisher said one of the problems for law enforcement is that they can’t tell the difference between hemp and marijuana, barring a chemical test to deduce the THC content that would have to be done in the state’s crime lab.

He says the lab is 400 drug exhibits behind every month because it is short staffed and underfunded.

Hemp can be used to manufacture products such as textiles, rope, insulation and animal feed, while it can also be grown for CBD oil extraction.

A large contingent of farmers on hand were supportive of the chance to help build a market for hemp.

“As a producer, I’d like to see hemp be allowed to be raised so that farmers would have the option of another crop in their rotation,” said Paul Dees, who represents the Delta Council on the task force and is a farmer himself.

According to the Michael Ledlow, the director of the Bureau of Plant Industry at the state Department of Agriculture and Commerce, hemp has no herbicides or pesticides certified for use with it by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Dr. Richard Summers, who is the associated vice chancellor for research at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, told the task force that the small amount of clinical trials into CBD oil’s effects on childhood seizures have enjoyed some positive results.

He said that the 10 young patients, all of whom had seizures that didn’t respond to traditional therapies, went three to four months without a single issue while using CBD oil produced at Ole Miss as a treatment.

Summers did offer that caveat that the sample size isn’t enough to draw a conclusion on CBD oil’s possible medical uses or safety and that the center plans to continue its research after being granted an extension by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

He said the goal was to develop a commercial CBD oil product for treatment of seizures.

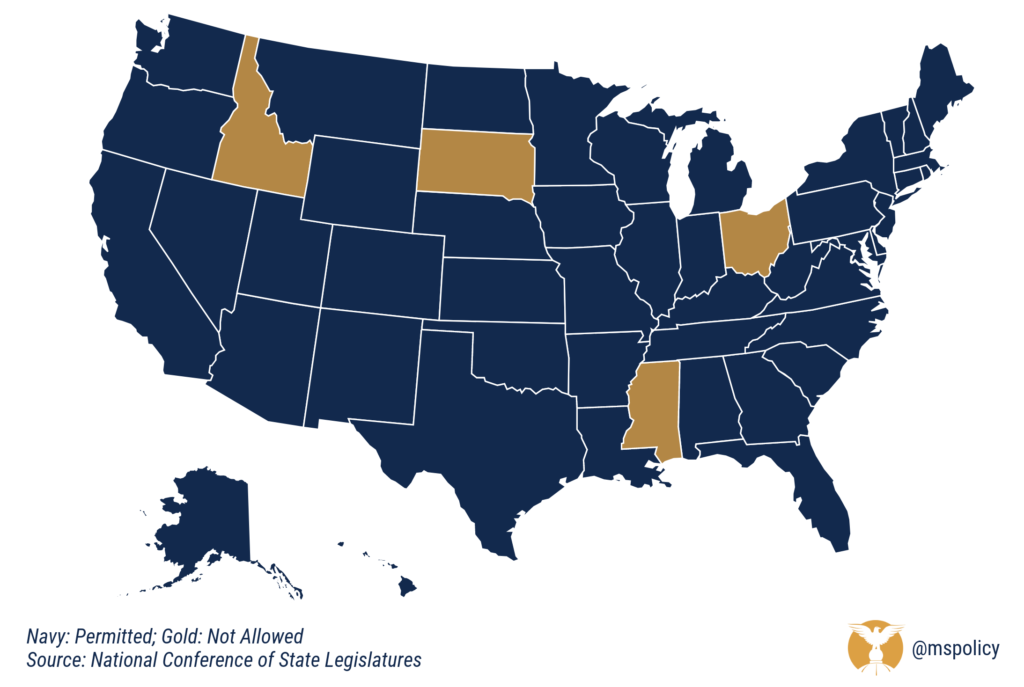

Cultivation of hemp for commercial, research, or pilot programs

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 46 states allow the cultivation of hemp for commercial, research or pilot programs. In fact, Mississippi is the only Southern state where the cultivation of hemp is illegal after a handful of states legalized it earlier this year.

The task force will meet again on September 25 at 10 a.m. There were four committees created at the meeting:

- Regulations and monitoring

- Economics, market and job creation

- Hemp agronomy

- Law enforcement

The four committees will submit reports at the next task force meeting.

If you’ve had an opportunity to check the news recently, you might have noticed a lot a talk about Ole Miss. And we’re not talking about their latest purchase of $4,500 trash cans. Though, that certainly should raise a few eyebrows.

It has now been roughly 230 or so days since Jeffrey Vitter announced his resignation as Chancellor of the University of Mississippi, making him the first person ever to resign his post, and in turn triggering a leadership vacuum.

With the departure, both state and local media have spent a great deal of time talking about who is in the hunt for the chancellorship. Yet not much has been written or said about what the candidates want to achieve.

The question the IHL, students, alumni, and facility should be asking those who seek the chancellorship is not what’s on their resume but what does their Ole Miss look like?

The university finds itself at a critical juncture – between the solidification of the progressive academic movement, centered on political correctness and multiculturalism, that has dominated the school for the last few years –and the real kind of progress in terms of academic rigor and freedom, diversity of thought and speech, citizenship, enrollment, and culture.

Going into this next academic year, Ole Miss will no longer be under NCAA sanctions, will be entering into its second year of being in the top half of one percent of research institutions, and will still be healing from the wounds inflicted by the demonstrations (related to Confederate monuments) which took place last April.

If any man or woman earnestly seeks to carry this office with the style, grace, acumen, humility, and effectiveness of former chancellors, then that potential leader should be communicating a bold plan for the future of Ole Miss. Such a plan should not include following the modern script of the edutocracy. Today’s academies of higher education suffer from many self-imposed wounds. America is losing faith in the value of sending its next generation of civic and business leaders to college. Reversing that dangerous trend is going to require someone with a clear vison but also with the intestinal fortitude to withstand the slings and arrows of the higher education establishment.

The university needs now, more than ever, a chancellor who holds a deep reverence for the school’s traditions and institutions as well as the opinions of its students and alumni. This chancellor will need to possess practical ideas for turning around declining enrollment, for increasing the number of in-state students, for strengthening academic programs across the board, and for creating an environment where free expression is preserved and cherished.

Ole Miss has the potential to be far greater than a mere punchline in the jokes made by the state’s political class. All it really needs is strong leadership. We’ve been there before. But strong leadership is in such short supply, especially if that leader is also required to bring terminal degrees and a publishing pedigree.

The search of the next chancellor isn’t just about whether the IHL picks someone who is qualified. There is no shortage of well-credentialed, academic administration careerists. I’m sure the list of qualified candidates is long and distinguished.

The most important qualification right now should be about a candidate’s vision for Ole Miss. What can it become? What should its graduates know? What principals and ideas underpin the institution in such a way that a degree is unmistakably valuable and unique? The people of the state of Mississippi, the alumni, the faculty, the students, and even the world, await the results of this incredibly important hire.

So what will Ole Miss become?

Mississippi won’t have to repay a $570 million Community Development Block grant given to the state after Hurricane Katrina, but most of the jobs created at the Port of Gulfport were low income and employment actually shrunk at the port itself compared with pre-Katrina levels.

Gov. Phil Bryant’s office recently announced that the U.S. Department Housing and Urban Development had closed its review of the Mississippi Development Authority and jobs created at the Port of Gulfport after Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

HUD provided a $570 million Community Development Block grant to the MDA for the port for repairs and upgrades such as wharf crane rail upgrades, ship channel dredging and delivery and installation of three ship to shore rail mounted container cranes, a project that wasn’t completed until 2018.

Under the conditions of the grant, the port was supposed to maintain 1,300 jobs and add 1,300 more workers once renovations were complete in 2016, 11 years after the storm. Fifty one percent were to be made available for those with low or moderate incomes.

Of those jobs, 1,167 came from a casino hotel that leases land from the port authority. HUD allowed the MDA to count jobs added at the Island View as part of its requirements under the CDBG grant. The agency also assisted the MDA in recalculating hours worked by the employees so they could be counted as full time under the conditions of the grant.

The state said that the port had 2,085 maritime employees prior to Hurricane Katrina and that number shrank to 1,286 by 2007. A study by the Stennis Institute that was attached to the governor’s news release said that the port and its tenants directly employed 1,121 personnel and generated $425 million for the local economy.

“HUD’s $570-million investment after Hurricane Katrina was invaluable to Mississippi,” Bryant said in a news release. “I’m proud to say that we’ve met the low and moderate income national objective for CDBG funds. This would not be possible without the effort from our federal and local partners.”

The Stennis study also blamed the Great Recession from 2007 to 2009 and the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill for the downturn in economic activity for having an effect on the Port of Gulfport’s operations after Katrina.

In August 2013, HUD issued a finding on the port reconstruction that criticized the state for inadequate recordkeeping in complying with the low- and moderate-income job requirements.

A report issued in September 2013 by the Joint Legislative Committee on Performance Evaluation and Expenditure Review (PEER Committee) predicted that the port would be unable to meet its job creation requirements by the deadline.

In 2017, the MDA told HUD officials that additional jobs had been created in the expansion of the Island View Resort. HUD examined records and found that 18 percent of the 112 new hires sampled were duplicative or employees had been rehired and counted twice and 25 percent of them never worked full time.

HUD met with MDA and port officials in August 2018 to discuss progress with complying with the job creation requirements. HUD found that only 588 jobs had been created, far short of the 1,200 jobs that were supposed to be added according to the state’s plan.

MDA also used a new methodology for counting full-time jobs at Island View toward the goal, converting part-time positions using hours worked into full-time equivalent positions.

The port has added some new tenants, such as McDermott International, Sea One and Chemours, and brought back fruit company Chiquita in 2016, which relocated in 2014 to New Orleans.

Edison Chouest subsidiary Top Ship was supposed to receive $36 million in state funds to open a shipyard on property on the Industrial Canal owned by the port and employ 1,000 workers that would count toward the HUD total. The deal was scuttled in December after Top Ship wasn’t able to meet the investment or job creation requirements.

Most of the 366 bills passed by the Mississippi legislature in this year’s session and signed by Gov. Phil Bryant become law on July 1.

Here’s everything of interest that is now law:

Good bills that became law

House Bill 1205 prohibits state agencies from requesting or releasing donor information on charitable groups organized under section 501 of federal tax law. The bill was sponsored by state Rep. Jerry Turner (R-Baldwyn).

HB 1352 is sponsored by state Rep. Jason White (R-West) and is known as the Criminal Justice Reform Act. The bill eliminates obstacles for the formerly incarcerated to find work, prevents driver’s license suspensions for controlled substance violations and unpaid legal fees and fines and updates drug court laws to allow for additional types of what are known as problem solving courts.

SB 2781, known as Mississippi Fresh Start Act, was sponsored by state Sen. John Polk (R-Hattiesburg). This bill eliminated the practice of “good character” or “moral turpitude” clauses from occupational licensing regulations, which prohibit ex-felons from receiving an occupational license and starting a new post-incarceration career.

The bill died for a time in the Senate on March 28, when the first conference report was rejected by the Senate. However, a motion to reconsider kept the bill alive and it was recommitted for further conference. The resulting second compromise was accepted by both chambers on the session’s final day and was signed into law by Gov. Phil Bryant.

SB 2901, known as the Landowner Protection Act, exempts property owners and their employees from civil liability if a third party injures someone else on their property.

The bill was sponsored by state Sen. Josh Harkins (R-Flowood). The version signed by the governor on March 29 allows civil litigation against property owners due to negligence based on the condition of the property or activities on the property where an injury took place. This was a major point of contention during debate over the bill.

HB 1613, also known as the Children’s Promise Act, allows an $8 million income tax credit for donations to charitable organizations that help children in need. The credit would increase the cap on individual tax credits from $1 million to $3 million and create a $5 million business tax credit.

Senate Concurrent Resolution 596 made Mississippi the 15th state to call for a Convention of the States authorized under Article V of the U.S. Constitution. The resolution was approved by the Senate and passed the House on March 27.

For a Convention of the States to occur, 34 state legislatures would have to pass similar resolutions.

Ugly bills that became law

HB 1612 authorized municipalities to create special improvement assessment districts that will be authorized to levy up to 6 mills of property tax (the amount per $1,000 of assessed value of the property) to fund parks, sidewalks, streets, planting, lighting, fountains, security enhancements and even private security services. The tax will require the approval of 60 percent of property owners in the district.

The Senate amended the bill so it only applies to Jackson (cities with a population of 150,000 or more).

SB 2603 reauthorized motion picture and television production incentives for non-resident employees that expired in 2017. The bill, as originally written, capped incentives to out-of-state production companies at $10 million. This was reduced in conference to $5 million and it was signed by the governor on March 28.

HB 1283 is better known as the "Mississippi School Safety Act of 2019.” Controversially, it requires school districts to develop and conduct an active shooter drill within the first 60 days of the start of each semester.

It also establishes a monitoring center connected with federal data systems with three regional analysts monitoring social media for threats.

The bill also creates a pilot program for six school districts with a curriculum for children in kindergarten through fifth grade with “skills for managing stress and anxiety.” The pilot plan would be federally funded.

New innovations continue to make our lives easier. If only the government would get out of our way and let consumers decide for themselves.

Because of new technology, getting around town can feel incredibly easy with companies like Uber and Lyft transforming the way we get from point A to point B. Users now have a choice in what was once controlled by a government-backed monopoly.

The new option is and was largely cheaper, easier, and more convenient. Though government tried, the city of Oxford in particular, ride sharing became so popular that there was little government could do to stop it.

But while ride sharing has changed how we travel, massive progress has also been made in the field of micromobility where customers can use electric scooters and bikes to travel to their desired destinations. This has helped to solve the first-mile and last-mile gaps for many.

In the past year dozens of scooter and bike companies have sprung up to meet the needs of consumers expanding to many major and midsized communities, along with college towns.

Yet at the same time, scooters have hit some roadblocks with city governments opting to ban the service, often describing it as a nuisance. Essentially, the same treatment ridesharing services received from Mississippi governments not too long ago.

Though scooters are generally designed for urban areas, of which Mississippi has few, residents of midsized communities, particularly college towns, could stand to benefit greatly from local deregulation.

Oxford and Starkville stand out as the most logical destination for scooters.

Students would no longer have to worry about parking or missing a bus to class as scooters or electric bikes could supplement their transportation needs. While scooters have never made it to Oxford, they lasted less than a month in Starkville.

The city brought scooters in on a trial basis, while Mississippi State had a ban in place. Naturally, the confusing laws led many students, the biggest user of scooters, to bring the scooters on to campus, drawing the ire of university officials. Lime, the scooter operator, decided to leave the city as a result. And students were again left without this option.

In larger cities like Jackson or tourist towns along the Coast, the introduction of scooters could radically transform how transportation is thought about.

The dangers of scooters are not different than the dangers of any other mode of transportation. There are people who are reckless, whether it's on a scooter or behind the wheel. We can control bad behavior without punishing everyone else. The government just needs to err on the side of individual liberty and personal responsibility.

Mississippi has some of the most consumer friendly laws in the country when it comes to buying and using fireworks.

You have probably noticed temporary firework stands set up near your house in the past couple weeks and that is because Mississippi has a defined selling period. Retailers can sell fireworks during the two busiest seasons; from June 15 through July 5 and from December 5 through January 2. And what retailers can sell and you can purchase is largely wide open.

But while state law provides for much freedom, many municipalities limit the use of fireworks in their city limits. Though not exhaustive, here is the rundown of whether fireworks are legal or illegal in Mississippi cities.

Fireworks are legal in the following cities:

Bay St. Louis, Horn Lake, Jackson (as of 2011), Natchez, Nettleton, Waveland.

The use of fireworks are banned in the following cities:

Aberdeen, Amory, Biloxi, Columbus, Corinth, D’Iberville, Diamondhead, Fulton, Hattiesburg, Hernando, Laurel, Long Beach, Meridian, Moss Point, Ocean Springs, Olive Branch, Oxford, Pascagoula, Pass Christian, Petal, Poplarville, Ridgeland, Southaven, Starkville, Tupelo, Vicksburg, West Point.

Disclosure: These regulations are based on recent news stories. Check with local authorities for most updated ordinance.

The default appears to be illegal, while it is largely legal in unincorporated portions of the counties.

One of the most common refrains from limiting fireworks is safety concerns and injuries caused by fireworks. But a 2017 report from the U.S. Consumer Safety Commission says “there is not a statistically significant trend in estimated emergency department-treated, fireworks-related injuries from 2002 to 2017.”

Rest assured, you are more likely to get injured from children’s toys then from fireworks-related injuries.

Noise is the other big complaint concerning fireworks, particularly after a certain time. Of course, municipal noise ordinances can and already do police that issue.

So as you celebrate the day which marks our freedom from the tyranny and oppression of another country, make sure you don’t run afoul with our own government regulators that have taken it upon themselves to limit your freedoms.

Civil asset forfeiture allows the government to confiscate property on the grounds that it is connected to a crime — without ever convicting someone of the crime. In court, a lower burden of proof applies in these civil cases than in criminal cases, even when valuable property such as the vehicle you drive to work is at stake.

Proponents of civil asset forfeiture will argue that such a practice is needed to keep illegal drugs out of Mississippi. That this is the best tool to stop drug mules from crossing Interstates 10 and 20 and reaching your neighborhood. But that argument quickly falls apart when you look at the latest data about the reality of how the practice is used both here in Mississippi and in the nation’s largest civil forfeiture program.

A review of the first 18 months of the state’s civil forfeiture database shows Mississippi law enforcement isn’t necessarily busting drug kingpins, but more likely collecting cash, an iPhone, or a vehicle if a person is in possession of an illegal substance.

The value of the 315 seizures in the database averaged $7,490 per seizure. When a single high-dollar forfeiture is removed from consideration, that average value drops to $5,422. Less than 10 seizures statewide amounted to more than $60,000.

The vast majority of seizures were for $5,000 or less and fully one-third were for less than $1,000. In two instances, law enforcement seized just $50 in cash. Since attorneys’ fees and court costs quickly add up to more than those amounts, many people don’t even try to contest a low-dollar forfeiture.

A newly released nationwide study also reveals that civil forfeiture fails to fight crime. The non-profit Institute for Justice published a study looking at the nation’s largest forfeiture program: the federal equitable sharing program. This is the Department of Justice program that allows local law enforcement to cooperate on forfeiture with DOJ agencies and receive up to 80 percent of the proceeds.

The study combines more than a decade’s worth of data from the equitable sharing program, with local crime, drug use and economic data from a variety of federal sources. It found that increased forfeiture proceeds did not help police solve crimes or reduce drug abuse. However, increases in forfeiture proceeds were strongly related to economic hardship. When local unemployment rose by 1 percentage point, forfeiture increased by 9 percentage points.

Many on the right and left have seen how this practice is unfair, and not in line with our principles. That is why there has been push back at the state level, and even from the U.S. Supreme Court in limiting this practice.

Since 2014, 31 states, including Mississippi, have reformed their civil forfeiture laws. In 2017, the state brought a transparency requirement to civil forfeiture and last year the legislature let the provision of administrative forfeiture die.

Other states have gone further. Seventeen states require a criminal conviction to forfeit most or all types of property. And three states – North Carolina, New Mexico, and Nebraska – have abolished civil forfeiture entirely. What does this look like?

New Mexico enacted sweeping reforms in 2015 abolishing civil forfeiture and replacing it with criminal forfeiture. To forfeit property, the government must convict the owner of a crime and tie that property to the crime with clear and convincing evidence in criminal court. This shifts the burden from the individual to the government, by requiring evidence that the person had knowledge of the crime giving rise to the forfeiture. And finally, all forfeiture proceeds must be deposited into the state’s general fund, eliminating the profit incentive that can distort law enforcement priorities.

Civil asset forfeiture violates fundamental property and due-process rights. If someone has been found guilty of selling or trafficking drugs, their property should be forfeited. But it should take a criminal conviction. That is the national mood, and movement.

States like North Carolina, New Mexico, and Nebraska have not become havens for drug dealers or seen spikes in crime. And again, the latest evidence shows that there is not a relationship between increasing forfeiture and decreasing crime and drug abuse. The choice between civil asset forfeiture and fighting crime is a false dichotomy. We know we can support law enforcement, safeguard our communities, and also protect the constitutional rights of all Mississippians.

This column appeared in the Clarion Ledger on June 30, 2019.

The Rankin County School Board has proposed a budget that calls for a tax increase from property owners.

The fiscal year 2020 budget, which was presented during a board meeting on Wednesday morning, includes a local increase of about $3.5 million from county taxpayers. The final budget will be adopted this fall by the Rankin County Board of Supervisors.

If the tax increase is adopted, taxpayers will be paying about $20 more per year on a $100,000 house with a 2 mill increase. Homeowners of a $200,000 house will be paying an additional $40.

Over the past decade, the millage rate in Rankin county has increased from 48.89 to 56.55. The increase would bump it up to 58.55 and represent an increase of almost 20 percent during this time period.

A look at the school district

The Rankin County School District is the third largest school district in the state, behind just Desoto County and Jackson Public Schools. And while the county continues to grow, the school district does not.

Enrollment in 2013 stood at 19,284. It hasn’t been that high since and the district estimates enrollment to be 19,150 for the upcoming year. School officials regularly use the word “stabilized” to describe the district’s enrollment. Essentially, the district is educating the same number of children eight years later, or even experiencing a slight decline.

| Year | Enrollment |

| FY2013 | 19,284 |

| FY2014 | 19,243 |

| FY2015 | 19,127 |

| FY2016 | 19,152 |

| FY2017 | 19,183 |

| FY2018 | 19,195 |

| FY2019 | 19,144 |

| FY2020 (estimate) | 19,150 |

These numbers are most noticeable in the early grades. While there were 1,509 students in kindergarten and 1,621 in first grade in RCSD in 2013, this past year there were just 1,365 and 1,438, respectively.

At the same time, the county’s population has increased from just under 146,000 to 154,000 today. So, people are moving to the county, and/ or having children, they just aren’t going to the district schools in the same proportion. And the district benefits from the revenue they receive for the children they don’t have to pay to educate.

This has helped the assessed property valuation to only increase. In 2013, it was $1.25 billion. It is now $1.47 billion.

| Year | Valuation (in billions) |

| FY2013 | $1.25 |

| FY2014 | $1.275 |

| FY2015 | $1.306 |

| FY2016 | $1.334 |

| FY2017 | $1.370 |

| FY2018 | $1.417 |

| FY2019 | $1.445 |

| FY2020 (estimate) | $1.474 |

The tax increase is intended to fund an increase to the local supplement for teachers and other personnel as well as additional safety and security expenditures. Both are important and worthwhile proposals that make very good sense and most would support. In fact, they should be near the top of any budget, rather than asking more of taxpayers.

Over the past decade, property value has increased by 17.6 percent while enrollment is slightly down. Rankin county taxpayers were hit with a tax hike just a couple years ago. Each time we are told “it’s only a few dollars.”

Perhaps another tax hike would be more tolerable if priority items – such as a teacher pay raise – were prioritized in the budget, rather than being the item the county uses to sell another hike.

Because when the county takes more money out of my pocket, my options are to either prioritize and cut expenses or earn more income through work. I can’t just propose an unbalanced budget (with more uses than sources) and expect someone else to pick up the tab.