Technology, creative disruption, and capitalism continue to work together to make our lives better and easier. Though there is often a desire by government to limit the full potential of new technology.

Having a personal shopper or getting fine dining delivered straight to your doorstep aren’t just luxuries for the ultra-rich these days. Now they’re available in a single click as mobile delivery apps continue to expand in their creativity and their delivery.

While these services may feel common in today’s society, they would have seemed otherworldly just 10 years ago. Instead of spending hours grocery shopping, you can have your groceries delivered to your front door, fine dining with the convenience of take out, and cheap rides on demand around the clock - leaving those who commute to work a less expensive alternative and those who drink and drive no excuse.

If you felt so inclined to take advantage of these conveniences, all you would have to do is place an order with any one of the dozens of delivery services available on the App Store,. Yet in Mississippi there may be something missing from your order – an adult beverage of your choosing.

That is because Mississippi has a prohibition on the delivery of alcohol with your meal. You can order that adult beverage if you sit down at the restaurant and eat. But when you order that same meal from the same restaurant via an app, that same drink cannot be included.

Mississippi is part of an ever-shrinking pool of states with such a policy. Last week, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott signed into law a bill legalizing home delivery of alcohol with your meal. And in doing away with outdated regulations, Texas sets a good example for Mississippi to follow.

Home delivery is about more than just drinking, it’s about the completion of an experience created by the free market. Customers benefit from being able to enjoy a drink with dinner or by saving another trip to the grocery store. Employees and employers benefit by an expanded consumer base, thus creating higher wages as well as new jobs. And the state benefits by introducing new revenue without the increase of taxes.

While they say everything’s always bigger in Texas, these benefits would make a pretty big impact right here in Mississippi, for the state and for the individual.

The technology is available. Convenience could be just a click away. If the government would let consumers choose.

Washington Post: Civil asset forfeiture doesn't discourage drug use or help police solve crimes

When you tell people who know little of our criminal justice system about civil asset forfeiture, they often don’t believe you. And it isn’t difficult to see why. It’s a practice so contrary to a basic sense of justice and fairness that you want to believe someone is pulling your leg, or at least exaggerating.

No exaggeration is necessary. Civil asset forfeiture is based on the premise that a piece of property can be guilty of a crime. Under the theory, if the police suspect that cash, a car, a house or even a business was obtained through proceeds of a crime (usually a drug crime), or was in any way connected to the commission of a crime, they can seize said property. The burden then falls on the property’s owner to prove that they either acquired it legally, weren’t using it in the commission of a crime, or that someone else used it illegally without the owner’s knowledge (though not all states offer the “innocent owner” defense).

ATR: MCPP joins conservative groups in opposing carbon tax

Today more than 75 conservative groups and leaders sent a letter to congress, united in opposition to any carbon tax.

Northside Sun: Rice receives 2019 Buckley award for conservative work

Mississippi Justice Institute Director Aaron Rice has been named a recipient of the 2019 Buckley Award, given annually by America’s Future Foundation. Aaron received the award for recognition of his work in helping to defeat the renewal of administrative forfeiture in the legislature this year.

“There is perhaps no honor greater for a young conservative than to receive an award in the name of William F. Buckley,” said Jon Pritchett, President and CEO of the Mississippi Center for Public Policy.

Monroe Journal: Our fair state takes baby steps toward change

The Fresh Start Act aims to make it easier for a person who was convicted of a crime to get a professional license. According to Brett Kittredge with the Mississippi Center for Public Policy, the bill will require licensing boards to have “clear and convincing standard of proof” in determining whether a prior criminal conviction is cause to prevent someone from receiving a license.

Now, you may be thinking people who have committed crimes or been addicted to drugs should just bear the weight of past mistakes indefinitely, or that these people should not take jobs away from those who have never convicted of a crime, but I think we all know someone who wears the scars of addiction or poor choices.

SuperTalk: MJI's Aaron Rice visits The Gallo Show

Mississippi Justice Institute Director Aaron Rice visited the Gallo Show to talk about a new rule that will expand emergency telemedicine in the state.

WLBT: Proposed regulation change could expand telemedicine in Mississippi

Telemedicine is connecting doctors and patients from afar all over the state. But regulations have been limiting the possibilities of using telemedicine in more emergency rooms. There’s only one way you’ll see telemedicine in a Mississippi ER - if UMMC is the provider. But that could soon change. Mississippi-based T1 Telehealth has been providing telemedicine in clinics and hospital but decided it wanted to offer its services in ERs.

“We wanted to do it in a way that we thought was a little bit less expensive, a little bit faster," explained T1 Teleheath CEO Todd Barrett. "So, we put together technology to allow us to be able to do that. We were blocked by this regulatory burden. We had a difficult time navigating this labyrinth of regulations.” They brought on the Mississippi Justice Institute to help navigate it. It’s a Board of Medical Licensure regulation that has prevented an expansion in this area of telehealth.

The Delta Health Alliance is a non-profit organization that receives most of its revenues from government grants and manages 52 education and healthcare programs in the impoverished Delta region in Mississippi.

The organization has four homes on its property for the use of its employees that are nearly three times as valuable apiece as the median home in the area. The DHA also receives an unbeatable deal on a lease for its headquarters.

The organization’s headquarters is located on land in Stoneville leased from the Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station. The organization has a sweetheart deal on its lease, paying Mississippi State University a symbolic $1 per year in a deal that expires in 2034.

This also means the organization pays no property tax on five structures valued at $2.83 million.

According to the organization’s most recent audit, the four executive in residence houses are valued at $843,378, or about $210,844 apiece. The office building is valued at $1,993,612.

The median home value in Washington County, Mississippi is more than $76,000, according to the National Association of Realtors.

From 2009 to 2011, the DHA tried to bill the Health Resources and Services Administration for more than $11,000 in maintenance and utility costs for the homes (it referred to them as cabins in paperwork filed with the government) under its Delta Health Initiative Grant.

Its justification was that DHA employees used the cabins as temporary residence while on travel and calculated the rate based on the federal per diem for a hotel in the area, $70 per night.

In a 2015 decision, the U.S. Health and Human Services Appeal board upheld the original determination by the HRSA to disallow the spending. They said the DHA didn’t show that the per diem costs were solely for employees working solely on grant-funded work.

In fairness, there could be a need for on-campus accommodations since there are only two small hotels located in nearby Leland. Greenville, which has several large chain hotels, is about 12 miles away from DHA’s Stoneville headquarters.

The DHA administers two Promise Neighborhoods (an Obama era U.S. Department of Education program), a medical clinic, headstart programs, anti-obesity, and anti-smoking programs among others.

The organization receives grants from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration.

Their CEO, Karen Matthews, has averaged more than $350,000 in pay, bonuses and benefits annually over the last seven years.

Everyone knows too well that gut punch when you receive a bill in the mail from a provider only to realize insurance has already been applied. Health care is expensive. We need a system that is firmly rooted in competition and market dynamics.

President Trump made lowering drug prices a campaign promise. To his credit, the president is working to address this issue. That’s why he tasked the Department of Health and Human Service Secretary Alex Azar to come up with a solution to address rising drug prices. We applaud this move by the President and support their objective of lower drug prices.

Unfortunately, Secretary Azar’s proposal to lower drug costs has an alarming feature — an “International Pricing Index” or IPI. This index would serve as a price control mechanism for Medicare Part B drugs sold in America. Part B drugs are the kind that are administered by a doctor usually as injections or infusions such as chemotherapy drugs, unlike the ones that are bought at a pharmacy and taken at home.

Alarmingly, the IPI would look at the prices of drugs in 14 foreign countries and use them as a base in the U.S. Many of these countries have socialized or government-controlled healthcare industries, and should not be looked to as an example for our own healthcare.

One of the reasons America is seen as the world leader in healthcare is the vast number of new drugs that are produced here. Because of our free market system, drug manufacturers can compete with one another to produce the best, most effective medicines in the world. Millions of patients all across the globe have benefited from a system of open competition that has led to the development of the majority of new drugs over the last several years.

However, the IPI could change all of that. Using artificial price controls could cut the legs out from under drug manufacturers and inhibit their ability to develop new, life-saving medicines. Producing a new drug is extremely expensive, sometimes costing as much as $2.6 billion for a single drug, according to Policy & Medicine. This is due to the high failure rate among experimental drugs, with 90 percent failing to gain FDA approval on average, according to BIO.

While the price of developing these drugs is high, it is necessary. Each new drug that makes its way to market has the potential to change millions of lives for the better. The IPI could be the start in taking that opportunity away from patients across the world.

Though the current proposal only applies to Medicare Part B drugs, if implemented, the IPI and other similar price control methods could quickly and easily spread to other areas of our healthcare system, and even to other industries. Socialism creeping into our economic model is dangerous. It does not work. It can sound good to certain segments of our population, but it has never worked. Wherever and whenever socialism has been tried, it has failed and humans have suffered by the millions. Competition and free markets do work and have made the United States the strongest economy in the world.

A better proposal was introduced in Congress that would lower prices for Medicare Part D drugs. The Medicare Part D Rebate Rule, as it is being referred to, would use free market solutions to lower drug prices instead of socialist price control measures. The rule would take the savings created through open negotiations between insurance plans and drug makers and pass those savings onto the sickest of seniors – not the middlemen who have historically pocketed the savings themselves.

Washington is doing the right thing by focusing on reducing drug prices and making healthcare access more affordable for patients all across the country. However, it is important that they remember to stick to using free-market solutions — like the Part D Rebate Rule — to accomplish this goal and stay away from using socialist price control mechanisms like the IPI.

This column appeared in the Clarion Ledger on June 12, 2019.

Mississippi taxpayers could soon be on the hook to cover part of the cost of restoring unprofitable passenger rail service to the Gulf Coast that was ended after Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

U.S. Sen. Roger Wicker (R-Mississippi) announced the award on Friday of a $33 million grant for infrastructure and capacity improvements from the Federal Railroad Administration.

The grant would pay for half of the cost of $65.9 million project to restore part of the eastern route of the tri-weekly Sunset Limited, which ran through the Mississippi Gulf Coast and connected Orlando, Florida with Los Angeles.

Under the grant, service would be extended to Mobile and require further contributions from Alabama and Florida to complete the route all the way to Orlando.

The service was terminated east of New Orleans in 2005 after Hurricane Katrina devastated the track and other infrastructure.

Mississippi’s share of the bill could add up to about $15 million, with Louisiana having already committed to spending $10 million for its part and Amtrak also adding funds.

The legislature could appropriate funds in the upcoming session after an attempt didn’t make it out of committee in this session. Senate Bill 2542, authored by state Sen. Brice Wiggins (R-Pascagoula), would’ve appropriated $4,696,500 toward Gulf Coast rail restoration and improvements to freight rail service in the area as well.

In Alabama, Gov. Kay Ivey is taking a cautious approach before adding her support to appropriating nearly $5 million state funds for the route.

She cited concerns with the Alabama State Port Authority as one reason for caution. Port Authority director Jimmy Lyons said in 2017 that passenger rail out of Mobile would be a major disruption to freight operations connected with the Alabama State Docks.

Advocates say that restoring rail service would help promote economic activity along the route. One of these groups is the Southern Rail Commission, which is seeking more extensive passenger rail in the South.

The SRC cites a May 2018 study by the Trent Lott National Center at the University of Southern Mississippi that says that construction and renovation of the rail lines on the Coast would add $34 million to the state’s economy. It also says restoration of passenger rail on the Mississippi Gulf Coast between Mobile and New Orleans would add $6 million annually to the economy.

The problem is that even Amtrak admits that restoring service will result in a hefty bill for taxpayers, since the quasi-public corporation relies heavily on federal and state subsidies to keep running.

A new Sunset Limited train that connects Orlando with Los Angeles wouldn’t be profitable and would require annual subsidies from taxpayers along the route. According to the latest statistics from Amtrak, the Sunset Limited route lost 2.6 percent of its ridership between fiscal year 2015 and 2016.

Amtrak’s own numbers in its 2015 feasibility study indicate that restoring service from New Orleans to Orlando would result in a $5.48 million loss annually.

Just running a roundtrip, standalone train from Mobile to New Orleans would yield a loss of $4 million. Having both a tri-weekly train from Orlando to Los Angeles and a separate round trip service between Mobile and New Orleans connection would result in an annual loss of $9.49 million.

This figure doesn’t include improvements to the rail infrastructure and stations along the route, which would cost, at minimum, $14,718,000 for just the restoration of passenger rail service and $102,954,000 for what the study says is a service level for ongoing operations.

Passenger rail hasn’t fared well in Mississippi, which has two Amtrak routes that pass through the state.

The Crescent train connects New Orleans with New York, while the City of New Orleans links the city with Chicago.

The most recent Amtrak numbers from 2017, show that the number of passengers boarding and detraining in Mississippi decreased from 118,200 in 2011 to 96,100 in 2018. That’s a decrease of nearly 18.7 percent.

According to the Amtrak 2015 feasibility study for restoration of rail service east of New Orleans, total trips declined from 148,387 in fiscal 1993 to 81,348 in 2005, a decrease of 45.2 percent.

Even taking into account that the federal government’s fiscal year ends on September 30, the numbers still pale when the final full year of service (2004) is considered, down 35 percent from 1993.

The study blamed delays with the train as one of the key factors in the lowered ridership. These delays, according to the study, were due to interference with freight operations from CSX — which owns the track between New Orleans and Mobile — and equipment malfunctions with Amtrak locomotives and passenger cars.

The Gulf Coast Working Group’s report to the U.S. Congress on restoring Gulf Coast rail service also mentions that limited space with rail yards and bridge crossings would “present a challenge to operating passenger trains on schedule.”

The Mississippi legislature this year reauthorized part of the Mississippi film incentive program that they let expire just a couple years ago.

Senate Bill 2603, which Gov. Phil Bryant signed in April, will bring back the non-resident payroll portion of the incentives program. This allows for a 25 percent rebate on payroll paid to cast and crew members who are not Mississippi residents. It expired in 2017 and the Senate had refused to consider it. Until this year.

Two other incentive programs have remained on the books. One is the Mississippi Investment Rebate, which offers a 25 percent rebate on purchases from state vendors and companies. The other is the Resident Payroll Rebate, which offers a 30 percent cash rebate on payroll paid to resident cast and crew members.

Film production companies, naturally, are excited. After all, they are the only winners in the race to the bottom known as film incentives.

“That bill effectively makes Mississippi as competitive as virtually any other Southern state from a production perspective in terms of movie producers trying to find places that they can most affordably come to make movies,” said Thor Juell, vice president of Village Studios and Dunleith Studios. “That is a big deal in terms of our ability to drive the economy of production and movie film making to Mississippi, and more specifically to Natchez. That is a big deal and that is effectively why I am here.

“I had previously been working in Louisiana,” Juell added, “and Louisiana has obviously had a long history of tax incentives there that have made them extremely competitive, and they’ve seen massive spikes in jobs and just the general outlying economic activity related to all the impending pieces. Mississippi, in my opinion, is even better.”

Better for some people, but not taxpayers

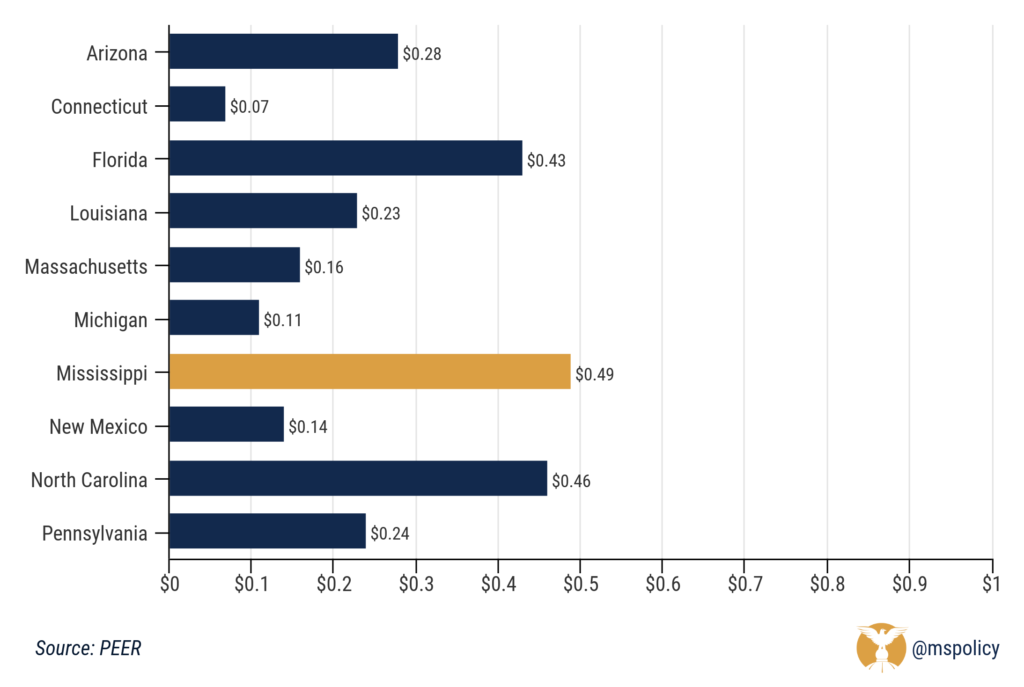

A 2015 PEER report shows taxpayers receive just 49 cents for every dollar invested in the program. That means that for every dollar the state gives to production companies, we see just 49 cents in return. If you or I were receiving that return on our personal investments, we would fire our financial advisor. Of course, no one spends his or her own money as carefully as the person to whom that money belongs.

For those looking at a bright side, we are actually “doing better” than many other states. This includes our neighbors in Louisiana, who recover only 14 cents on the dollar. They also have one of the most generous programs in the country; it was unlimited until lawmakers capped it a couple years ago. (Other reports show the Pelican State recovering 23 cents on the dollar, but either way it’s a terrible investment.)

Beyond Mississippi and Louisiana, film incentives are a poor investment throughout the country. Numerous studies have been conducted on film incentives. All sobering for those worried about taxpayer protection. Here is a review of the return per tax dollar given, courtesy of the PEER report.

That is why the number of states offering film incentives is diminishing. Not in Mississippi though.

No one can blame Juell or anyone else in the film industry for wanting or taking advantage of incentives. They are in business to make money. Yet, the state shouldn’t allow them to do so at the expense of taxpayers. Rather, the state should be working to reduce the tax burden on all companies, regardless of whether or not they have lobbyists in Jackson.

When Mississippi State and Ole Miss play in the Super Regional round in the NCAA baseball tournament this weekend, the majority of players in the dugouts and on the field will likely be paying some or most of their tuition and other costs.

The reason is college baseball’s nonsensical scholarship limit. Right now, Division I schools can only offer 11.7 scholarships that can be divided up among 27 players.

Most players don’t receive a full scholarship and the minimum that can be awarded is 25 percent. Try to do that math in your head for kicks.

The National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics, which is an organization for smaller college athletic programs, offers an even 12 scholarships in baseball.

NCAA Football Championship Subdivision (once known as Division I) football, in comparison, offers 85 scholarships. The difference is that football generates lots of revenue and most college baseball programs lose money. Lots of money.

According to the most recent NCAA’s revenue and expenses report from fiscal 2016, 114 Division I schools played baseball and the average program had a $658,000 loss.

At the next highest level, the Football Championship Subdivision, the average program lost $93,000. This level can offer only nine scholarships per year.

In addition to the revenue issue, any additional scholarships for baseball would have to be offset under Title IX with additional ones for women’s sports. Considering that baseball is a money loser for most schools like most women’s sports, the scholarship number will likely remain where it is.

College football became a revenue monster because of TV contracts with the various conferences, which have revenue-sharing agreements that allow even the also-ran teams on the field to enjoy the largesse.

College baseball is a regional, warm weather game with little interest outside the Southeast and Pacific coast. Even with the rise of conference networks, there is only a smattering of college baseball games broadcast during the regular season.

For example, one team from the Midwest, Michigan, advanced to the 16-team Super Regional round. That means potentially lucrative TV markets (and the resultant advertisers) in the Midwest and Northeast are shut out with little interest by viewers.

Even the biggest winners on the diamond are struggling financially.

The Southeastern Conference is the 900-pound goliath of college baseball, with six of its teams advancing to the Super Regional round. Despite the success, most of its individual programs aren’t making money.

According to a 2017 story in the Baton Rouge Advocate, only four SEC baseball teams made a profit or even broke even in 2016. Ole Miss barely made a profit (more than $28,000), while LSU made $1.5 million.

The rest, which includes Mississippi State, lost money on baseball that year. This was before State’s new Dudy Noble Field opened for business in 2018, with its array of luxury suites and other revenue-enhancing features.

For college baseball to get more scholarships, increasing revenue like Mississippi State did with its state-of-the-art stadium is going to be the rule. Some schools in the Snow Belt, such as Buffalo University, will decide to phase out baseball.

Getting a national TV contract for the stronger conferences would probably help grow the sport and its fanbase.

Even if those things come to fruition, just getting the sport to a nice, even 12 scholarships might be a tough battle.

Eliminating the math headaches for college baseball coaches trying to divvy up their precious few scholarships might make that a worthy effort.

It would take the average person more than 13 weeks to wade through the 9.3 million words and 117,558 restrictions in Mississippi’s regulatory code.

This is according to an analysis from James Broughel and Jonathan Nelson at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. They have taken a deep dive into the regulatory burdens of each state, including Mississippi.

What do regulations look like in Mississippi? In terms of government subdivisions, the biggest regulator, by far, is the Department of Health, with more than 20,000 regulations. That is followed by the Department of Human Services with over 12,000 regulations, and 10,000 plus regulations for state boards, commissions, and examiners. The most regulated industries were ambulatory healthcare services, administrative and support services, and mining (except oil and gas).

Overall, Mississippi was middle of the pack when it came to administrative regulations. It would take 31 weeks to read all 22.5 million words in the New York Codes, Rules and Regulations, which has 307,636 restrictions. But regardless of the state, there is generally one consistent – the number of regulations are only increasing.

Regulatory growth has a detrimental effect on economic growth. We now have a history of empirical data on the relationship between regulations and economic growth. A 2013 study in the Journal of Economic Growth estimates that federal regulations have slowed the U.S. growth rate by 2 percentage points a year, going back to 1949. A recent study by the Mercatus Center estimates that federal regulations have slowed growth by 0.8 percent since 1980. If we had imposed a cap on regulations in 1980, the economy would be $4 trillion larger, or about $13,000 per person. Real numbers, and real money, indeed.

On the international side, researchers at the World Bank have estimated that countries with a lighter regulatory touch grow 2.3 percentage points faster than countries with the most burdensome regulations. And yet another study, this published by the Quarterly Journal of Economics, found that heavy regulation leads to more corruption, larger unofficial economies, and less competition, with no improvement in public or private goods.

A prescription for lowering the regulatory burden on a state is the one-in-two-out rule, or a regulatory cap. In 2017, one of President Donald Trump’s first executive orders was to require at least two prior regulations to be identified for elimination for every new regulation issued. This is badly needed. We have gone from 400,000 federal regulations in 1970 to over 1.1 million today.

Many years ago, British Columbia took on a similar mission. And in less than two decades, their regulatory requirements have decreased by 48 percent. The result has been an economic revival for the Canadian province.

And one state has the unique ability to rewrite their book on regulations. This year, the state of Idaho essentially repealed their entire state code book when the legislature adjourned without renewing the regulations, something they are required to do each session because the state has an automatic sunset provision.

Now, the governor of Idaho is tasked with implementing an emergency regulation on any rule that should remain. The legislature will consider them next year. There are certainly needed regulations, just as there are unnecessary or outdated regulations that serve little purpose. But, the difference is, the burden on regulations now switches from the governor or legislature needing to justify why a regulation should to be removed to justifying why we need to keep a regulation.

Whether it’s a sunset provision or one-in-two-out policy, Mississippi should move in the direction toward a smaller regulatory state with more freedom. And if a regulation is truly important to our well-being, let the regulators prove why. In a state in need of economic growth, let’s find a way to remove unnecessary barriers and inhibitors.

This column appeared in the Starkville Daily News on June 6, 2019.

Mississippi is the nation’s most dependent state on federal funds and, if Louisiana is any guide, the addiction to federal money would only worsen if Medicaid was expanded.

Federal funds for Louisiana increased 41.63 percent between 2016, before Medicaid was expanded, and 2019.

In Mississippi’s newest $21 billion budget which goes into effect on July 1, 44.5 percent of revenue comes from federal sources. Only 27.26 percent came from the state general fund (state taxes such as income and sales) and 25.32 percent sourced from other funds, such as user fees.

Medicaid ($4.94 billion in federal matching funds) represented 52.63 percent of all federal funds appropriated for Mississippi.

Medicaid covers 674,544 enrollees in Mississippi or about 22.6 percent of the state’s population.

Adding other social welfare programs, such as Temporary Aid to Needy Families (TANF) and Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP), bring that social welfare’s share to 68.57 percent of federal outlays for the state.

The percentage has changed little in the past four years, with an average of 44.37 percent of the state’s revenues coming from federal sources. Also not budging was the percentage represented by social welfare spending, which averaged 67.72 percent of federal money appropriated for Mississippi.

The Tax Foundation ranked Mississippi as the state most dependent on federal funds as a percentage of its revenues, with Louisiana second.

Expanding Medicaid as Louisiana did in 2016 would only worsen this dependence compared with the rest of the nation.

So far, 36 states have expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, which is more commonly known as Obamacare. The ACA dictates that the federal government cover 90 percent of the costs for expanding eligibility to all individuals earning less than 138 percent of the federal poverty level.

In Republican Gov. Bobby Jindal’s final $28.2 billion budget in fiscal 2016, the Pelican State received 34.98 percent of its budget from federal funds. More than 62 percent of that was for Medicaid ($5.87 billion in federal funds alone).

By 2019, the state’s budget ballooned to $33.99 billion under Democrat Gov. John Bel Edwards, with 41.53 percent of all revenue coming from federal sources.

Medicaid spending ($9.81 billion in federal match) accounted for 69.51 percent of all federal revenue appropriated for Louisiana.

According to the Louisiana Department of Health, 465,871 adults had enrolled in Medicaid expansion as of May 8, 2019, which was a decrease from 505,503 as of April. The state could have as many as 1.7 million people or 37 percent of the state’s population enrolled in Medicaid.

According to a report by the Louisiana-based Pelican Institute, state officials expected 306,000 new enrollees when it expanded Medicaid eligibility.