According to a recent study, it would take more than 13 weeks to wade through the 9.3 million words and 117,558 restrictions in Mississippi’s regulatory code. Yet we know little about many of those regulations, such as if they are even necessary today.

The Mercatus Center at George Mason University’s James Broughel and Jonathan Nelson wrote a policy snapshot of Mississippi’s regulatory state as part of a national project to analyze regulatory burdens nationwide.

These regulations can impose huge costs as businesses are forced to comply with them and can also become anticompetitive devices, since many of them are written by the industries that are being regulated.

Mississippi is roughly mid-pack in the amount of its regulatory framework. But the one consistent among most states is that the number of regulations are only increasing.

That changed in a big way in one state.

Idaho has a somewhat unique regulatory process. Each year, the state’s regulatory code expires unless reauthorized by the legislature. While this does provide a check that is missing in places like Mississippi, it is normally a formality. But not this year.

Now, Idaho Gov. Brad Little is tasked with implementing an emergency regulation on any rule he would like to keep. The legislature will consider them next year. And there are certainly needed regulations, just as there are unnecessary or outdated regulations that serve little purpose.

But, as Broughel has pointed out, the burden on regulations now switches from the governor or legislature needing to justify why a regulation should to be removed to justifying why we need to keep a regulation.

To reduce red tape, Mississippi could move toward a sunset provision similar to Idaho or introduce a regulatory cap that orders the removal of two old rules each time a new one is added. A thriving economy is one with fewer regulations, a lighter government touch, and more freedom for small and mid-sized businesses.

If a regulation is so important, prove it.

Mississippi Justice Institute Director Aaron Rice has been named a recipient of the 2019 Buckley Award, given annually by America’s Future Foundation.

The Buckley Awards recognize “outstanding young professional conservatives for their above-and-beyond service to the conservative movement.” The award is in honor of William F. Buckley, who became a leader of the early conservative movement before the age of 30 by founding National Review in 1955 and hosting the public affairs television show, “Firing Line,” for 33 years. This is the only such award in the freedom movement that focuses on the achievements of liberty-minded young professionals.

“There is perhaps no honor greater for a young conservative than to receive an award in the name of William F. Buckley,” said Jon Pritchett, President and CEO of the Mississippi Center for Public Policy. “He inspired a generation of conservative intellectuals to fight boldly for foundational beliefs. That is exactly what Aaron has done since he joined the movement, but it’s also what he has done all of his life.”

Aaron received the award for recognition of his work in helping to defeat the renewal of administrative forfeiture in the legislature this year. Administrative forfeiture previously allowed agents of the state to take property valued under $20,000 and forfeit it by merely obtaining a warrant and providing the individual with a notice. In order to get the property back, an individual was required to file a petition in court within 30 days and incur legal fees in order to contest the forfeiture and recover such assets.

But due in large part to Aaron’s thought leadership through state and national op-eds, television, and radio, the renewal died without receiving a vote in committee.

“I am honored to be able to bring this award to the Mississippi Center for Public Policy, and its legal arm, the Mississippi Justice Institute,” said Rice. “Our work on administrative forfeiture was very much a team effort. I would not have been able to make any meaningful impact on my own. While I have the honor of receiving the Buckley Award, I consider it a team award to our entire organization, and the first we have been honored with. I could not be happier to be a part of that recognition for our great organization.”

“Aaron’s contributions to advancing the free society, to improving people’s lives and to working tirelessly against amazing odds in Mississippi has inspired all of us,” said Cindy Cerquitella, Executive Director of AFF. “Aaron’s work to secure the private property rights of Mississippi citizens, against the desire of so many in power is a true testament to his patriotism and commitment to the values of a free society.”

This is the first time the award has been presented to a state-based think tank that focuses exclusively on one state. Previous winners include Christina Sandefur of Goldwater Institute, Rob Bluey of Heritage Foundation, Mollie Hemingway of The Federalist, and Jim Geraghty of National Review.

Read Aaron’s full interview with America’s Future Foundation here– including more about his work in the conservative movement and some fun facts about his life.

In the debate over a wood pellet mill that is being built in George County near Lucedale, both sides are missing a key point.

The pro-mill side says Enviva’s $140 million pellet mill and a $60 million loading terminal at the port in Pascagoula will provide more markets for the state’s generous timber resources. The anti-mill side argues from an environmental viewpoint and that the mill would bring a danger to state residents due to increased health risks from emissions and airborne particles.

No one is talking about what the mill will cost taxpayers. Taxpayers statewide, through the Mississippi Development Authority, will be providing $4 million in grant funds, with $1.4 million for a water well and a water tank, while the other $2.5 million is for other infrastructure needs and site work.

George County will provide $13 million in property tax breaks over the next 10 years.

The company is expected to hire 90 employees in Lucedale, with 300 loggers and truckers possibly finding work supplying logs to the company.

All of those incentives, if realized, could add up to $17 million or about $188,888 per job.

The lost revenue will have an effect on George County’s budget over the next decade, especially since counties don’t receive sales tax revenue. According to the most recent audit from April 24, George County received $8,445,185 in property taxes.

Over the last four years, the county has taken in $32,051,659 in property taxes, an average of $8,012,915. Extrapolating this over a decade, the county could be expected to take in about $80 million in property taxes.

If Enviva realizes all of the property tax breaks, the county will lose 13.9 percent in potential revenue.

George County property tax receipts

| 2017 | $8,445,185 |

| 2016 | $8,278,200 |

| 2015 | $7,962,400 |

| 2014 | $7,365,874 |

The only winner during the first decade of the deal with Enviva might be the city of Lucedale, which could see a boost in sales tax revenue from the plant.

According to data from the Mississippi Department of Revenue, the DOR has disbursed $18,386,882 in sales tax revenue to the city from 2010 to 2018. The DOR disburses 18 percent of the state’s 7 percent sales tax to municipalities. In 2017, sales tax revenue ($2,204,988) represented 46.8 percent of the city’s $4.7 million budget.

Enviva is the world’s largest wood pellet producer and produces pellets to fuel overseas power plants. It has seven mills in the Southeast and one of those mills is in Amory, acquired in August 2010.

These wood pellets are made from low-grade wood fiber unsuitable for lumber because of small size, defects, disease or pest infestation; parts of trees that can’t be processed into lumber and chips, sawdust and other residue. The plant will mill, dry and pellet the wood in a press, using natural polymers in the wood called lignin to act as a natural glue.

Unnecessary and burdensome regulations make it harder for Mississippians to earn a living.

According to a new report from Pete Blair with Harvard University and Bobby Chung with Clemson University, occupational licensing reduces labor supply by an average of 17-27 percent. An earlier report from the Institute for Justice found that Mississippi has lost 13,000 jobs because of licensing requirements.

While licensing was once limited to areas that most believe deserve licensing, such as medical professionals, lawyers, and teachers, this practice has greatly expanded over the past five decades.

Today, approximately 19 percent of Mississippians need a license to work. This includes everything from a shampooer, who must receive 1,500 clock hours of education, to a fire alarm installer, who must pay over $1,000 in fees. All totaled, there are 66 low-to-middle income occupations that are licensed in Mississippi.

The new report also looks at the varying requirements for occupational licensure, including prohibitions on those with criminal convictions, whether the conviction had anything to do with the occupation or not.

This year, the legislature passed a new law that prohibits occupational licensing boards from using bureaucratic rules to prevent ex-offenders from working. The law requires occupational licensing boards to eliminate blanket bans and “good character” clauses used to block qualified and rehabilitated individuals from working in their chosen profession.

Under the Fresh Start Act, licensing boards must adopt a “clear and convincing standard of proof” in determining whether a criminal conviction is cause to deny a license. This includes the nature and seriousness of the crime, the passage of time since the conviction, the relationship of the crime to the responsibilities of the position, and evidence of rehabilitation. The law also creates a preapproval process that allows ex-offenders to determine if they may obtain a particular license before undertaking the time and expense of training, education and testing. In addition, the law protects licensed individuals who fall behind on their student loans from losing their occupational license.

All too often, occupational licenses only serve to protect certain industries, rather than protecting public health or wellbeing. We should continue to look for ways to help people find gainful employment rather than implementing unnecessary roadblocks. Working provides purpose and the opportunity for families to flourish. We should do everything possible to encourage it.

The $1,500 teacher pay raise could be a net positive for the health of the state’s defined benefit pension system but that would require future earnings forecasts meeting projection targets, according to analysis of data by the Mississippi Center for Public Policy.

The good news is the increased contributions to the Public Employees’ Retirement System of Mississippi could add up to as much as $677 million over the next 30 years. This added revenue will mean more money will be available to pay benefits to retirees and give the plan more to invest.

One problem is the projected benefit payments, which will increase by $878 million over the next 30 years ($29.26 million annually) when compared to the previous projections.

The market value of the plan’s assets could increase as much as $2.9 billion over the next three decades, but that depends on a steady return on the investments of 7.75 percent, an assumption that hasn’t been lowered by the plan’s governing board since 2015.

The catch is the plan’s forward looking projections could be in error, as the plan’s actuaries rely on several generous assumptions that include:

- Income from the plan’s investments, 7.75 percent.

- Price inflation, three percent.

- Salary increases, 3.25 percent.

Using those assumptions above, the original projections have the plan 99.6 percent funded by 2048.

A recent report by PERS actuaries suggests the assumed rate of inflation they use to make future projections should be lowered from 3 percent to 2.75 percent to reflect changes in their forecast prediction models.

The way this number was computed was to use the future-looking projections by the PERS actuaries, which provide guidance for the retirement fund’s governing board as a starting point and other data from the state superintendent’s annual report and the Public Employees’ Retirement System of Mississippi’s comprehensive annual report.

To find the most likely number of Mississippi teachers requires using the extra appropriation needed for the $1,500 raise ($14 million more than the original $58 million) and the formula used by the Mississippi Department of Education to compute the amount.

When the agency submitted the information to lawmakers, it multiplied the number of teachers listed in MDE computers (31,157) by 1,500 and multiplied the result by 25.05 percent for fringe benefits to arrive the $58 million figure.

Using that data, Mississippi K-12 teachers represent about 25 percent of the 150,867 contributing members to PERS and 63.34 percent of the state’s 60,952 employees in K-12 public education. Using the larger figure, that would add up to about 38,260 teachers.

Multiplying the projected PERS payroll by 25.6 percent and the percentage of the $1,500 raise (3.34 percent) yields larger payroll numbers which affect total contributions to the plan.

The first 10 years of projected benefits data were excluded since the raise’s effects will be minimal on those retiring at that time.

The best way to calculate the effect on benefit payments is to use the plan’s projections for the first decade and focus on the following 20 years. Multiplying the benefit payments by percentage of PERS members that are teachers (25.6) and the amount of the raise (3.34 percent) gives an idea of how much they would affect this crucial area.

PERS beneficiaries also receive a generous annual cost of living increase, 3 percent, that compounds every year after they reach age 60.

In addition to the $1,500 raise passed by the legislature last session, teachers also receive small, annual raises once they complete two years of service, according to the pay schedule published by the MDE. Teachers are paid according to their qualifications and years of service.

In 2018, PERS received $570,807,000 (employees contribute 9 percent of their income to PERS) from state, county and city workers and $1,018,163,000 from their employers (taxpayer contributions will increase in the new fiscal year from 15.75 percent of payroll to 17.4 percent).

Divide that further and the state’s 60,952 employees in K-12 public education contributed $230,891,431 to PERS in 2018 while the employer contribution to their retirement added up to $411,846,933 for a total of $642,738,364.

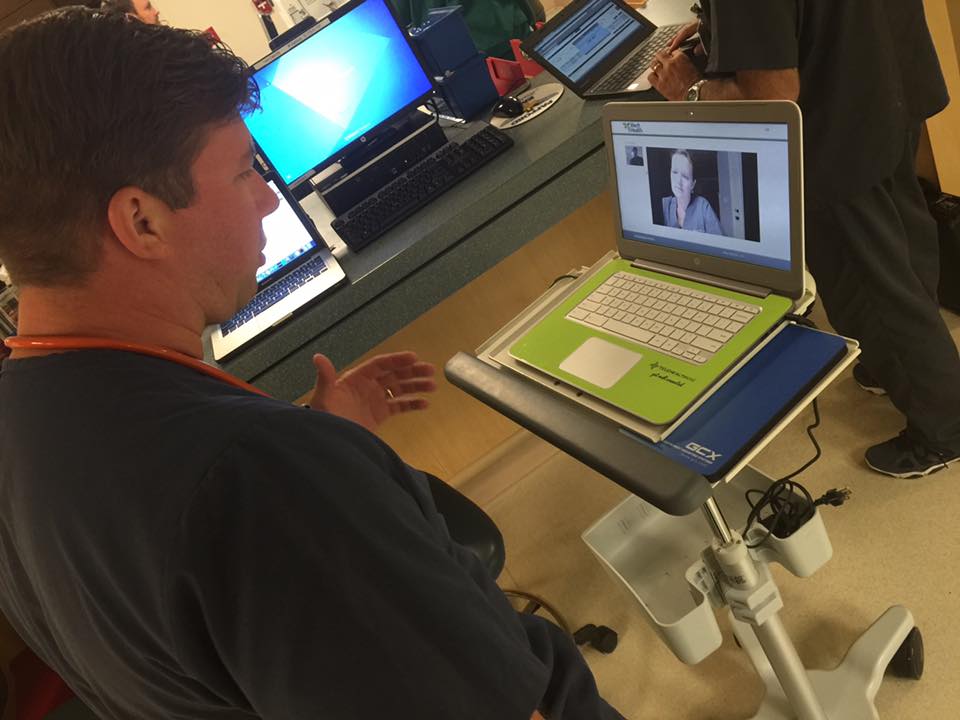

T1 Telehealth is a Mississippi company that provides innovative telemedicine services, but has been limited in the healthcare it can deliver because of government regulations that hampered competition.

The Mississippi Justice Institute has been representing T1 Telehealth in its efforts to challenge these regulations. On May 9, 2019, after months of negotiations, the Mississippi State Board of Medical Licensure adopted a new proposed rule that will expand telemedicine services in the state by allowing additional providers to offer telemedicine in the emergency room.

“The new regulations will be a great development, not just for T1 Telehealth, but for all telemedicine providers, for small rural hospitals that rely on telemedicine, and for patients across Mississippi,” said Aaron Rice, the Director of the Mississippi Justice Institute. “The Mississippi Board of Medical Licensure took the right approach to make the regulations fair and to increase access to healthcare in Mississippi.”

In Mississippi, there are 64.4 primary care physicians for every 100,000 residents, far below the national median of 90.8. Many rural hospitals struggle to fund and staff their emergency departments, which require multiple emergency room physicians to take turns covering shifts to ensure 24/7 access. Emergency telemedicine allows these small hospitals to keep their emergency rooms open, by staffing them with physician assistants and advanced practice registered nurses. When a patient arrives, an emergency medicine physician in another location uses audio/visual technology and other tools to see the patient, and to instruct the nurse or physician’s assistant on the care that is needed.

The old regulation prohibited physicians from providing emergency room telemedicine services to small hospitals unless they worked at a Level One Hospital Trauma Center with helicopter support. Mississippi only has one Level One hospital in the state, so there was no competition for this service. However, any physician who is board certified in emergency medicine is capable of providing emergency telemedicine services, and is able to transfer a patient by helicopter, regardless of the type of hospital the physician works for. The old regulation locked out companies like T1 Telehealth, which was the first private telehealth company in the state, even though the company saw a need and believed it could provide better emergency telemedicine services. The new regulation will now allow new companies to compete.

“The thing that Americans like better than anything is choice,” said Todd Barrett, CEO of T1 Telehealth. “People want to have the opportunity to say I don’t like that, but there’s this other option I can try and two competitors in a market understand that. They both strive to be the one people are going to call. That makes everything better and cheaper by helping to keep costs down and improve quality. There are two ways to differentiate ourselves and that’s either price or quality. This new regulation allows us to come in and prove ourselves, show how much better it is, what the results are, and how patients benefit.”

For Barrett, innovating in healthcare is all he has ever done. It is what he knows. Since graduating from Pharmacy School in 1988, he has started and sold three pharmacy companies and a technology company, each time sensing and filling a need.

“Can we create something that allows more patients to be treated and made better with less dollars and if it looks like that we’re interested in seeing how we can fit in and make that happen,” Barrett added.

The new proposed regulation will be filed with the Secretary of State to allow time for public comments. It will also be reviewed by the Occupational Licensing Review Commission before becoming final. Once the regulation is finalized, many expect to see a new, vibrant market emerge in the provision of emergency telemedicine services.

A new federal grant program and an emerging technology could be the tools used by the state’s non-profit electric power associations to get high-speed internet to their customers.

On April 12, Federal Communications Commission Chairman Ajit Pai announced a proposal to award $20.4 billion over the next decade toward rural broadband networks in a program called the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund.

This would be repurposed money from the FCC’s Universal Service Fund which already provides money for extending rural broadband service in addition to low-income phone service and low-coast broadband access for schools and libraries.

Thanks to a change in state law, EPAs in mostly-rural Mississippi are well placed to enter the reverse auctions to receive grants from the new federal program. A reverse auction differs from a conventional one since it has one buyer and many potential sellers.

It would increase Mississippi’s reliance on federal funds.

The Mississippi Broadband Enabling Act was signed into law by Gov. Phil Bryant, went into effect immediately and it allows the state’s 26 EPAs, also known as cooperatives, to provide broadband to their primarily rural customer base.

The new law requires EPAs to conduct economic feasibility studies before providing broadband services, maintain the reliability of their electric service, maintain the same pole attachment fees for an EPA-owned broadband affiliate as for private entities wishing to use the EPA’s infrastructure and submit a publicly-available compliance audit annually.

According to data from the latest FCC wireless competition report, there is a digital divide in Mississippi. Ninety-five percent of urban residents in Mississippi have access to high-speed internet service (defined as 25 megabits per second). In rural areas, only half of residents have access to that level of internet service. In 12 of the state’s 82 counties, five percent of the population or less has access to high-speed internet.

In 27 counties, only 25 percent or less of the population has high-speed internet service available.

The technology that might bridge the divide in Mississippi and in other rural states could be 5G (fifth generation) wireless. Signals in 5G operate on three different spectrum bands that include:

- Low band — 600 megahertz, 800 megahertz and 900 megahertz.

- Mid band — Frequency bands of 2.5 gigahertz, 3.5 gigahertz and 3.7 gigahertz to 4.2 gigahertz.

- High band — 28 gigahertz, 24 gigahertz, 37 gigahertz, 39 gigahertz and 47 gigahertz (millimeter wave or high band).

5G can also be supported on unused parts of the spectrum below 4 gigahertz, which is the frequency range used by present 4G LTE coverage.

Right now, the FCC has already started auctioning bandwidths in the low band. A recent report by the watchdog group Citizens Against Government Waste recommends that FCC also conduct spectrum auctions with strong oversight for mid band, with the proceeds going to taxpayers.

According to the report, since 1994, the FCC has conducted 101 spectrum auctions that have generated $121,672,180,000 for taxpayers with the awards of 44,499 licenses. The report also says the mid band auction could generate an additional $11 billion to $60 billion for taxpayers, depending on how much of the spectrum is put on the market.

5G will be much faster, capable in urban areas of speeds of 100 gigabits per second for the high band, which is 100 times faster than 4G. Also, 5G has the advantage of low latency, which is the time that passes between when information is received and when it can be used by the device on the network. This means it could be used to replace conventional WiFi.

Since 5G uses shorter wavelengths, the antennas can be much smaller, which means a tower can support more antennas. This allows 1,000 more devices per meter than what’s supported by the existing 4G network.

The problem with high band is these wavelength have a much shorter effective range. They require a clear line of sight between the mobile device and the antenna. These signals can easily be blocked by solid objects, rain and even humidity, which would be a problem in sweltering Mississippi summers.

Also, 5G download speeds in rural areas would be only fractionally as quick as those in urban areas with large numbers of antennas, which would be supported by trunk lines made of fiber-optic cable.

These issues would provide complications for using 5G as the means to extend high-speed internet service to rural areas of Mississippi.

The marketplace is already working on solutions.

AT&T has been testing a way to use power lines (Project AirGig) to deliver 5G service. The technology has already been successfully tested in Georgia and internationally. The company says it could be used to bring high-speed internet to customers in suburban and rural neighborhoods.

Mississippi has among the most limiting cottage food laws in the country.

Passed just a few years ago, Mississippi’s cottage food operators law allows those who bake or prepare goods at home to sell them to the public without a government inspection or certificate. Because of this law, those who had long been baking without asking government now had permission from the state.

But the law limits gross annual sales to less than $20,000. This is the third lowest sales cap in the county, according to a report from the Institute for Justice.

Among states that have cottage food laws, only South Carolina ($15,000) and Minnesota ($18,000) have lower caps. Seven other states have a similar $20,000 cap, including Alabama and Louisiana.

Our two other neighboring states, Arkansas and Tennessee, however, have no cap. They are two of 28 states that do not place a limitation on what you can earn.

Cottage food limitations by state

| State | Sales cap | Online sales | Restaurant/ retail sales |

| Alabama | $20,000 | No | No |

| Arkansas | None | No | No |

| Louisiana | $20,000 | No | Yes |

| Mississippi | $20,000 | No | No |

| Tennessee | None | No | No |

Among states that have a sales cap, the average is just under $29,000.

Who are cottage food operators?

According to the IJ report, 83 percent of cottage food producers are female while more than half (55 percent) live in rural communities.

Just a few (20 percent) consider this there main occupation. Forty-two percent say it is a supplementary occupation and 35 percent categorize it as a hobby. And the most significant benefit for most operators was the ability to be your own boss and have flexibility and control over the schedule. Indeed, the ability to balance work and family was a top consideration for female business operators, along with the low operational costs.

This year legislation would have lifted the cap to $35,000. While there shouldn’t be a cap, that would have been an improvement. It passed the House, but failed to make it out of the Senate.

While most cottage food operators are micro-enterprises, some do or would like to grow into sizeable operations. And we should support that.

After all, that should be the goal of the state, to encourage growth. Cottage food businesses enhance the financial and personal well-being of their owners. They provide an in-demand product to a willing consumer. And they positively benefit sales tax collections for the state.

There has not been evidence to suggest that lightly regulated states pose a threat to public health as some like to indicate. The limitations really just serve to limit competition for established businesses. By eliminating restrictions in Mississippi, we can give consumers new options, grow the economy, and encourage entrepreneurship.

Men have recently started competing against women in sports, and winning. Is that fair?

If the Equality Act becomes law, it will become much more common. This bill, which is backed by nearly 300 members of Congress, will assuredly pass the House this year and be a top priority issue for any future Democratic Senate or White House.

Under the proposed legislation, all federally funded entities would be required to interpret “sex” to include “gender identity.” If a man identities as a woman, they are to be treated as a woman. That includes, notably, high school and college sports.

Why have men and women always competed separately when it comes to sports in the first place? And why are they still? We are in the 21st century, right? A woman can do anything a man can do and even more, right? Believe me, I am all about girlpower.

But as equal as the sexes are, our biology will never be the same. The objective of equality of outcomes is fundamental, but the objective of the equality of outcomes is fundamentally flawed.

On a very basic level, the two genders are divided not because of their genders, but because the biological gender they are born with results in certain hormonal levels which have a lot to do with the level of athletic ability that person can achieve. One particular hormone is testosterone. You will find much more of this in men. In fact, men’s testosterone levels are around 280 to 1,100 Nano grams per deciliter while women’s normal levels are between 15 and 70 Nano grams per deciliter. This hormone increases bone density, and causes muscle mass growth and strength. It also triggers facial hair growth, so women everywhere should be thankful our bodies don’t produce more of that.

In light of this difference, pitting genders against one another physically would not challenge either competitor to achieve their highest athletic ability.

However, there are female athletes with a much higher level of testosterone than the average female. This includes Caster Semenya, a 2016 Olympic gold medalist in middle-distance running. The International Association of Athletics Federations has attempted to regulate situations such as these by making a separate classification for athletes of Difference of Sexual Development (DSD) and will require those athletes to reduce their blood testosterone levels if they want to compete internationally. For some, situations like Semenya, justify allowing transgender women to compete with biological women. But using a statistical anomaly on the very outer bounds of the distribution mean of physiological traits to set policy for all is scientifically absurd.

What exactly happens when a male declares himself to be female? Do his hormone levels drop to match that of the average woman automatically? And as a result of that, does his athletic ability suddenly change to match that against whom he competes? Does his lung capacity decrease? How about his body fat percentage and muscle mass, does that change? No. Simply, when a man begins the process of becoming a transgender woman, he goes on hormone reducers. On the other hand, when a woman begins the transition from female to male, she is put on steroids, raising the level of testosterone.

Over time, these hormonal changes affect the individual’s body. But it won’t change them completely. Transgender women will still have more muscle mass and higher bone density than the average cisgender female, allowing them an athletic advantage, in a way, like Semenya. These advantages are physiological. They are present as a result of nature, not as a result of societal pressures or oppressive expectations.

As a former collegiate athlete, the idea that a subpar male athlete could declare himself a female, then swoop into women’s sports, dominate, and bump girls out of the running to receive a college scholarship, or win a state title, or get to playoffs, or compete at a national level, strikes me as taking opportunities away from women, not the other way around.

Girls and women should not be told to accept this as the new normal. In the name of progress and equal opportunity, it’s the height of irony to tell women they should just accept a scientifically un-level playing field which clearly discriminates against their gender.

In case we have forgotten, the strides women have made in sports have been rather recent. Of those who competed in the 2014 Olympics, 40 percent were women, compared to 2.2 percent in the 1900 Olympic games. The Women’s National Basketball Association has only been in existence for 23 years. National Pro-Fastpitch was only established in 2004. The Women's Tennis Association has been around for less than 50 years. Sports have opened numerous doors for women, but those doors have not been open long.

Why would we let men, claiming they know what being female is like, come in and boot us out of our own opportunities?

The attempt to allow men to compete in women’s sports, or the larger Equality Act, is simply an attempt to erase the reality of biological sex. It’s absurd.