Mississippi could soon be surrounded on three sides by states that have school choice. Arkansas has already passed legislation establishing universal education freedom. Alabama and Louisiana may not be far behind.

Might we see something similar in Mississippi?

Speaking on SuperTalk the other day, Lieutenant Governor, Delbert Hosemann, sounded wonderfully upbeat about school choice. He said that he expected there to be “multiple school choice bills” presented during the 2024 state legislative session.

However, Mr Hosemann then suggested that any such reform may need to be restricted in its scope. Why? Because he said, under Mississippi’s constitution “you can’t put government money into private schools”.

The Lieutenant Governor raises an important point. As the case for universal school choice becomes increasingly difficult to ignore, we need to examine what Mississippi’s constitution actually says. Does our state constitution really preclude Mississippi from implementing Arkansas-type reform?

Section 208 of the Mississippi Constitution states that:

“No religious or other sect or sects shall ever control any part of the school or other educational funds of this state; nor shall any funds be appropriated toward the support of any sectarian school, or to any school that at the time of receiving such appropriation is not conducted as a free school.”

It could not be clearer, opponents of school choice will say. No public money can be appropriated for private schools.

Except, of course, with Arkansas-type school choice, public money is not appropriated for private schools. It is appropriated to families, who receive 90 percent of the prior year’s net public school aid budget paid into their child’s Education Freedom Account. This they can then spend on a school of their choice, public, private or home school.

Claiming that under such a scheme money is being appropriated to private schools would be like claiming that part of your wages are being appropriated to Target, simply because you chose to spend some of your salary there.

Fortunately, it turns out that the argument that Mississippi’s constitution prevents universal school choice is not a slam dunk after all.

In his interview on SuperTalk, the Lieutenant Governor was also quite right to refer to a case currently before the courts concerning the use of pandemic relief funds paid to private schools.

During Covid, large sums of federal money were provided to states like Mississippi to distribute to eligible recipients for disaster relief and to spur economic recovery. The Mississippi legislature, in turn, authorized a state agency to distribute about $10 million of those federal funds to private schools for infrastructure improvements.

This prompted a legal challenge brought by the activist group Parents for Public Schools, who argued that Section 208 made such payments unconstitutional. A Hinds County chancellor agreed. The Mississippi Supreme Court is now reviewing the case on appeal.

What if the Supreme Court rules that it was unconstitutional to give $10 million of pandemic relief funds to private schools? Would that mean Arkansas-type school choice is now considered unconstitutional in our state, as Mr. Hosemann seemed to imply?

Not at all. In fact, MCPP’s legal arm, the Mississippi Justice Institute, recently addressed that very question in the pandemic relief litigation. Teaming up with our friends at the Institute for Justice, we filed a “friend of the court” brief with the Mississippi Supreme Court to ensure the point was clear.

Here is what we told the Court.

Even if the Court ruled that the provision of $10 million in federal relief funds to private schools was unconstitutional, that decision would not prevent Mississippi from enacting school choice programs, including those available to families using non-public schools.

Why not? Because the Mississippi Constitution only prohibits the appropriation of state education dollars for institutional aid to non-public schools. It does not prevent the state from providing individual aid to students who choose to use those funds for tuition at non-public schools. Indeed, to avoid future confusion on that point, we asked the Court to explicitly say so in its ruling.

Moreover, as our legal brief points out, it is not just the text of the Constitution on our side. Precedent from the Mississippi Supreme Court supports our view as well. Over 80 years ago, the Court decided Chance v. Mississippi State Textbook Rating & Purchasing Board, 200 So. 706 (Miss., 1941). In that case, the Court upheld a law that appropriated funds to purchase textbooks and distribute them to students, including those in non-public schools. Why? Because the program was designed to benefit the students, not the schools.

Far from precluding school choice, Mississippi’s constitutional law is favourable to it.

There are plenty of legitimate (if misguided) arguments against having universal school choice in Mississippi. Claiming that the Mississippi Constitution prevents it is not one of them.

In every single one of the half dozen US states that have now adopted school choice, there was a legal challenge to try to prevent it from happening. There will no doubt be legal challenges to school choice when – not if – it eventually happens here. The fact that such cases will be brought against universal school choice is not a case against passing legislation to allow it.

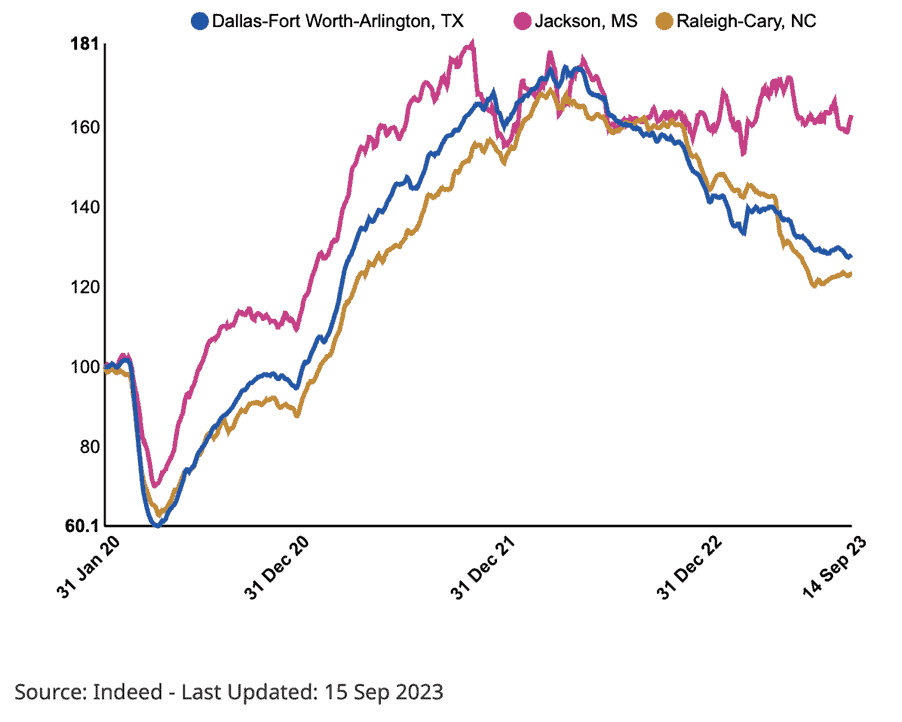

Job hiring website, Indeed.com, has published data showing the Jackson metro area to be one of the best performing metro areas in America for new job postings.

According to Indeed’s job posting index, the Jackson metro area jobs postings are 54 percent higher now than they were in February 2020. Of all the metro areas in America, only Phoenix in Arizona and Spokane in Washington performed better than Mississippi’s state capital.

“Indeed’s data on jobs growth shows Jackson Mississippi is outperforming most other American cities when it comes to jobs posting growth since February 2020” explained Douglas Carswell of the Mississippi Center for Public Policy.

“The Jackson metro area has since that time outperformed cities such as Raleigh, North Carolina and even Dallas, Texas in terms of new jobs postings on Indeed”.

“Clearly this is only one set of data from one job hiring firm, but it is indicative of a broader trend we are now seeing in Mississippi”, Carswell continued. “This state is on the up”.

“Since Governor Tate Reeves signed into law a universal occupational licensing law, and with all that inward investment flowing into the state, the jobs market has picked up. Mississippi is now part of a wider southern economic success story”.

China is going to become the world’s number one economic superpower, we were told. And as China takes off economically, they said, she is going to become just like the rest of us.

This is what I call the China fallacy, and neither of the assumptions that underpin it are true.

China has indeed had three decades of double-digit growth. Her take off has been so spectacular, China went from being a largely agrarian economy that accounted for less than 2 percent of world output in 1980 to almost a fifth of output now.

But far from becoming more like us, China under President Xi seems to be becoming not just un-Western, but increasing anti-Western.

Twenty years ago, when China was admitted to the World Trade Organisation and President Clinton talked of China as a ‘strategic partner’, all the clever people in Washington said China would move our way.

By letting China join the international system, the experts said, China would become part of it. Think of all those tens of millions of middle class Chinese, they assured us. Soon, like the middle classes in America and Europe, they would be demanding all the trappings of liberal democracy.

Two decades later China is busy trying to subvert the international order. Chinese foreign policy seems to be all about creating rival structures and processes. Chinese government agents engage in the kind of espionage activities you might expect from a hostile foe.

Those that perpetuated the China fallacy used to tell us that following the British handover of Hong Kong, China would grow to become more like Hong Kong. Instead, the opposite has happened. Hong Kong has been brought into line with the rest of China, and what limited freedoms her people had have been taken away.

Far from taking her place at the international table, China behaves as if she wants to overturn it. China amasses troops in the western Pacific, bullying Taiwan and making little secret of her plan to invade the island. This would be the moral equivalent of the United States threatening to annex Vancouver Island.

Rather than becoming more Western, China’s government continually seeks new ways to restrict her citizens from accessing the internet. Digital technology has been harnessed to monitor the day to day activities of her own people. The autocrats that preside over China are so thin skinned and morally bankrupt, then actively clamp down on the Falun Gong movement. This would be the moral equivalent of the US government trying to shut down yoga classes.

The assumption that China, under the communist party, is ever going to emulate the West is wrong. Wrong, too, is the other side of the China fallacy – the assumption that China is destined to be a great superpower.

For as long as I can remember, highbrow magazines have been publishing articles forecasting that China’s economy will overtake America’s. At one time, we were told this would happen in the 2020s. Then it was the 2030s. Now I read it is supposed to happen before 2050.

I predict that China’s economy will never overtake America’s. Only last year, China ceased to be the most populous country on the planet, as India overtook her. China’s demographic future looks ominous.

Today there are 1.4 billion people in China. By the end of this century, some estimate that China’s population will have fallen about 40 percent to 800 million.

The next few years will see a significant fall in China’s economic growth, I suspect.

It is relatively easy to produce big gains in economic output when you move farm workers into factories (see Soviet Russia in the 1950s for details).

China was able to accelerate economically as a consequence of Deng Xiaoping’s reforms. Deng’s policies were not only market-friendly. Under Deng, decision-making was relatively decentralized. Maritime provinces had lots of autonomy. Beijing did not try to pre-empt every decision.

Under Xi, China has abandoned the Deng reforms, and reverted to what you might call the Ming tradition of top down control. It is not an encouraging precedent.

Far from being an economic dynamo, China is on course to becoming the next Japan. Like China, Japan was once supposed to overtake America. Instead, a previously thriving, export-driven economy has been reduced to stagnation by demographics and debt.

China may not become the world’s economic superpower, but this does not mean that China is not a threat. Quite the opposite.

Just over a century ago, a recently industrialized power, Germany, started to challenge the international order. Economically and militarily powerful, Germany nonetheless sensed that other powers were not so far behind. Among German’s leaders there was a sense that if Germany was serious about rearranging the furniture in Europe, she had a limited window of opportunity to do so. The consequences of that mindset were catastrophic.

My fear is that China under the communist party sees herself caught in a similar window of opportunity. Her demographic calamity, coupled with slow growth, mean that her relative power will only decline.

America is right to be strengthening her fleet in the Pacific (Three cheers to Mississippi Senator, Roger Wicker, for providing such leadership on this – America will be safer for it). It is also important that America works with an alliance of countries, including Australia and Japan to ensure the security of the Pacific.

China might not be the world’s number one economic power, but I suspect she will be the world’s biggest geopolitical headache for the foreseeable future.

Mississippi’s top 50 public officials now cost the taxpayer over $10 million a year for the first time. The state’s top 50 highest paid officials saw their salaries increase 5 percent from an average of $193,678 last year to $205,000 this year.

According to the 2023 Mississippi Fat Cat report, published by the Mississippi Center for Public Policy, Mississippi now has some of the highest paid public officials in America.

Mississippi’s State Superintendent for Public Education has made over $300,000 per year for a number of years now. Mississippi also now has two local school superintendents each earning about a quarter of a million dollars a year.

Forty percent of those on the Fat Cat list are school superintendents, who enjoyed bumper pay rises. Those school superintendents on the Fat Cat list received an average 14% pay increase, taking them to over $200,000 a year.

The $10.3 million cost salary of Mississippi’s 50 highest-paid public officials would be enough to pay the salaries of:

- 189 nurses (at $54,284 per year)

- 178 State Troopers (at $57,680 per year)

- 191 teachers (at $53,699 per year)

- 227 Mississippians receiving the median income ($45,180 per year)

Mississippi’s 50 Fat Cats are paid more than America’s 50 state governors. While the 50 Mississippi Fat Cats receive a combined total of $10.3 million a year, the combined salary of America’s 50 state governors is a mere $7.4 million.

The Humphreys County Superintendent, for example, with a mere 1,257 students, is paid more than the governor of Texas, with a population of 30 million.

The Jackson Public Schools Superintendent, who oversees a district with approximately 20,000 students, makes more than the Governor of Florida, which has a population of more than 21 million.

Fat Cat pay does not necessarily reflect public service performance. Some of the highest-paid public officials preside over some of the worst education outcomes.

The Fat Cat report acknowledges that some highly paid officials provide good value for money for the taxpayer, and that high salaries in the public sector are not necessarily a bad thing.

However, the report also recommends changes to ensure that there is accountability when it comes to top public sector pay. Suggestions include:

- Requiring a greater degree of oversight by the legislature when it comes to significant salary increases.

- Using a state-mandated formula to calculate the maximum allowable salary for school superintendents.

- Restricting the amount of education funding that can be spent on administration.

- Potentially amending Section 25-3-39 of the Mississippi code to remove many of the exemptions to restrictions on unapproved limits.

A link to the report can be found here.

Last week I was in Little Rock, Arkansas to learn about something called the LEARNS Act. The brainchild of Arkansas 47th governor, Sarah Huckabee Sanders, this bold new approach to education across the river is drawing a lot of national attention.

Under Arkansas’ LEARNS Act, every child is allowed an Education Freedom Account. The state will then pay into that account 90 percent of the prior year’s average per pupil spending. To give you an idea, that could be about $10,000 per year.

Mom and Dad in Arkansas will then be able to allocate that money to pay for their child’s tuition, school fees, school supplies and even school transportation costs. Moreover, the parents can chose to spend that money in a public school, or a private school, or even through home-schooling.

Listening to some of the key architects of Arkansas’ LEARNS Act, I discovered that there is a lot more to it than school choice. The new law puts great emphasis on improving standards in literacy and math.

Indeed, one lawmaker I was talking with explained how Arkansas has intentionally copied Mississippi, with an insistence on teaching kids to read using phonics. Clearly Mississippi’s focus on phonics has not gone unnoticed in Little Rock. The LEARNS Act also has an ambitious plan to improve math performance, too.

Looking at some of the detail of the LEARNS Act, Arkansas seems to have followed Mississippi’s lead in combating Critical Race theory, too. Under the LEARNS Act, teachers will not be required to attend training on this divisive ideology. The Department of Education’s material will be reviewed to ensure it does not conflict with the idea of equal protection under the law.

As Mississippi did recently, Arkansas’ LEARNS Act gives teachers a substantial pay raise. From 2025, the minimum teacher salary will be $50,000 a year. Interestingly Arkansas has also implemented a merit-based teacher pay scheme. Teachers across the river can now earn up to $10,000 a year bonuses.

Under the LEARNS Act, school district superintendents in Arkansas are now required to have performance targets tied to student achievement. The days of ignoring poor performance in remote school board districts are over.

While Arkansas has clearly learned somethings off Mississippi, there are things that Mississippi could learn from our friends in Little Rock.

Arkansas and Mississippi share more than just a river. Both states are of similar size and population. Each state has a Delta, and neither state has a particularly large urban area. If education freedom works in Arkansas, it will become much harder to keep resisting it over here.

The most inspiring thing about my visit to the Governor’s Mansion in Little Rock was not perhaps getting to see the bust of President Clinton (curiously someone had placed it behind the railings, making it look like Bill was behind bars). What was most inspiring was having the chance to see Governor Sanders.

She is so full of energy and enthusiasm. When she talks about the need for change, she makes an overwhelming moral case. Indeed, I was reminded of another strong, principled conservative leader I once knew called Margaret Thatcher. Both of them have a steely determination, coupled with principled beliefs. The 47th Governor of Arkansas is going to go far.

My visit to Little Rock, happened to coincide with Governor Sanders announcement of plans to dramatically reduce the state income tax. When it comes to income tax reduction, Arkansas is doing what Mississippi has done already, which is wonderful to see. It is great to see good ideas moving both ways between our two states.

Twenty two years ago America was hit by a horrific terrorist attack. Like many readers, I can remember exactly where I was when I first heard that a plane had struck the Twin Towers.

An entire generation of young Americans has, of course, been born since that terrible day, with no recollection of an event many of us can never forget.

That makes it vital that we take a moment this year to think about September 11th 2001. We should remember the victims who headed out to work that day expecting to see their loved ones again. We should remember the heroes, too, especially those on flight 93, whose selfless actions saved many lives.

Let us not forget, either, why it was that a group of savages in a distant land should want to commit such an atrocity.

Over the past two decades a myth has emerged that the attack on the Twin Towers was somehow pay back against American interference in Iraq or Afghanistan. This idea, surprisingly widespread in Europe, puts the cart before the horse.

America invaded Iraq and Afghanistan in response to the attack on the Twin Towers. The invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan could not possibly have been a cause of it.

Islamist terrorists first attempted to blow up the Twin Towers way back in 1993. At that time, America’s direct involvement in the Middle East had been largely limited to the liberation of Kuwait – at the invitation of Arab leaders. Indeed, America had had precious little direct military involvement in the region since Ronald Reagan pulled US peacekeepers out of Lebanon in 1983.

No, the real reason Islamist terrorists attacked America 22 years ago is because America exists.

Why does the existence of America offend the Islamists? It’s not about Israel or George Bush. America is resented by Islamists because the United States represents not only a better way of life, but the best way of life yet lived by any portion of humankind.

Cultural relativism, an often well-meaning belief that every way of life is equally valid, is so pervasive among America’s elite, I fear it blinds them to the truth; there is no better place to live your life than in the United States of America.

The United States is founded on a revolutionary set of principles that emerged out of the European Enlightenment – that each of us is created equal and in possession of natural rights. The US is governed not by theocrats, but by a Constitution written by men.

Even more galling for the Islamist fundamentalist, this American system works.

Think of the southern US border today. Thousands of people from every part of the planet are clamouring to get into the United States. They are not trying to make their way into Yemen or Syria.

If, like the Islamists, you believe that the path of a perfect society is to order it in accordance with fundamentalist Islamist principles, the evidence from Iran, Sudan or Libya is not entirely encouraging for your cause.

One of the first acts of America’s first President, George Washington, was to state explicitly that it was not enough to merely tolerate religious differences. Henceforth in this country, he wrote to the Jewish congregation in Newport in 1790, people of every faith should “enjoy the exercise of their inherent natural rights”.

That idea of religious freedom must be hard to take if you believe that you alone have an understanding of the divine.

These are the principles on which America was founded, and they are a better way of organizing a society than every other way ever attempted.

Perhaps most important, we should remember the brave Americans who stepped forward after the attack on the Twin Towers to protect the American way of life. Thanks to many thousands of brave acts – some big, some small, some documented, others untold – they have helped keep this country, and the West, largely safe ever since. Thank you.

The shame of it! Mississippi has found itself in the humiliating position of being compared disobligingly to the United Kingdom. Just last week, the Financial Times ran a column asking, “Is Britain really as poor as Mississippi?”

Most Mississippians do not spend much time worrying about comparisons to Britain. The same cannot be said about those on the other side of the Atlantic. For Brits—and I am one, though now based in Jackson, Mississippi—the issue of whether they are more or less prosperous than Mississippi has become a thing. Indeed, the Financial Times now calls it “the Mississippi Question.”

It was nine years ago that Fraser Nelson, the editor of The Spectator, first suggested that the U.K. was poorer than any U.S. state but Mississippi. This came as an uncomfortable shock for many in Britain for whom the word Mississippi conjures up clichés about the Deep South, as a byword for backwardness. Every time anyone has made the comparison since, there has been an indignant outburst from Britons keen to denounce the data.

In practice, when it comes to trying to provide a definitive answer to the Mississippi Question, no uniform, up-to-date set of data exists. But if you take the most recent U.S. figures for GDP per state, divide it by the population of Mississippi, you get a pretty accurate figure for GDP per capita in current dollar values. Make the same calculation for the U.K., with total GDP data divided by the population, and you end up with two comparable numbers.

Last year, by my math, the U.K.’s output per person was $45,485; Mississippi’s was higher, at $47,190. If Britain were invited to join the U.S. as the 51st state, its citizens would be at the bottom of the table for per capita GDP. Some might say that for Mississippi, that is still disconcertingly close.

“That’s not fair!” the critics would counter. “When you compare the wealth of nations, you need to look at how far the money goes. Things cost more in the U.K. than in Mississippi.” To adjust the raw numbers, the argument goes, you need to use an economist’s tool called Purchasing Power Parity. Sure enough, when you consider differences in the price of things in Britain and America, the U.K. does appear richer than Mississippi. Thus, after such PPP adjustments, the Financial Times analyst suggested that for 2021 Mississippi’s per capita GDP was a mere $46,841 to the U.K.’s $54,590 (though conceding that, without the London effect, much of Britain was relatively poorer than the Magnolia State).

“Hold on!” we on Team Mississippi retort. “Why adjust the numbers for our state using U.S. national data?” Here, a dollar goes a lot further than it would in New England or on the West Coast. To produce PPP-adjusted numbers for Mississippi that reflect the buying power of a dollar in places like New York or San Francisco, we say, is absurd. And sure enough, tinkering with the numbers to reflect purchasing power in Mississippi itself makes it doubtful that the U.K. would still come out ahead.

Perhaps more interesting, however, than how you cut the numbers for any given year is the fact that the gap between Mississippi and Britain seems to be growing. Never mind PPP. Just run the numbers for GDP per capita in current dollars for the first part of 2023, rather than 2022, and see that Mississippi’s output is rising at a faster rate than Britain’s.

Over the past 30 years, several southern states have seen rapid economic growth. States like Texas and cities such as Nashville have become economic hubs to rival California or Chicago. North Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, and even Alabama have all flourished. Mississippi was missing out. Until now.

Historically, business in Mississippi was highly regulated. Licenses used to be mandatory in order to practice many of even the most routine professions. The state has now lifted a lot of these restrictions, deregulating the labor market. According to a recent report by the American Legislative Exchange Council, a group representing conservative state legislators, the size of Mississippi’s public payroll has been pared back. In 2013, there were 645 public employees per 10,000 population; today, the number is down to 607. Last year, Mississippi also passed the largest tax cut in recent history, reducing the income tax rate to a flat 4 percent.

How did this come about? Policy makers here have drawn inspiration from the State Policy Network, a constellation of state-level think tanks, borrowing ideas that have worked well elsewhere. We got the idea for labor-market deregulation from Arizona and Missouri. Tennessee inspired us to move toward income-tax elimination. Florida’s success stands as an example of how we could reduce more red tape.

What was once just a trickle of inward investment has turned into a steady flow. Growth is up, visibly: The areas of prosperity along the coast and around the state’s thriving university towns are getting larger, even if pockets of deprivation in the Delta remain.

Perhaps many in Britain find it hard to accept that Mississippi has overtaken them economically because they still think of Mississippi as cotton fields and backwoods poverty, peopled by folk who subsist on God, guns, and grits. But what if Britons’ reluctance to face changing economic realities comes from an outdated perception of themselves?

Most of my fellow Brits like to think that they live in a prosperous free-market society. They have not fully grasped the way in which their country has been sleepwalking toward regulatory regimentation. Stringent new regulations on landlords have seen thousands of owners pull out of the market, resulting in a dire shortage of rental accommodation. New corporate diversity requirements have imposed additional costs across the financial-services sector, with little evidence that bank customers are getting a better deal. Restaurants are required to display a calory count for each serving on their menus.

Individually, none of these restrictions matters all that much. But together, this relentless micromanagement inhibits innovation and growth. And Brits have become so accustomed to government red tape, they no longer seem to see the crimson blizzard that blankets so many aspects of their economic, and even social, life.

To be fair to them, for many years it did not seem to matter that taxes rose and the regulatory burden grew heavier. Thanks to the use of monetary stimulus in place of supply-side reform since the late 1990s, the country’s economy seemed to defy gravity, engineering the sort of growth that high tax and tight regulation might otherwise preclude. Few in the U.K. seemed to notice as ever more aggressive doses of monetary stimulus were required to stave off a downturn. Only now that the option of further monetary stimulus has been exhausted are the cumulative consequences of 30 years of folly becoming apparent.

To recognize that one’s country has been run on a false premise for three decades is difficult. To have to acknowledge that Britain is now poorer than the poorest state in the Union could prompt a moment of self-reckoning that many Brits seem determined to postpone.

Britain’s recurrent fixation with the Mississippi Question tells us as much about the country’s state of mind as it does about GDP. Rather than confront uncomfortable truths, my countrymen dispute the data. Instead of facing up to the consequences bad public policy in Britain, many blame Brexit, or Ukraine.

Putin’s war on Ukraine might have caused higher energy prices, but it alone does little to explain Britain’s poor economic performance. As for Brexit, though opinion formers who originally opposed it love to blame the country’s woes on it now, they never seem to ask why, if leaving the European Union was the cause of Britain’s lack of growth, Britain has still managed to outperform much of Europe.

Since Britain voted to leave the EU in 2016, the U.K. economy has grown by 5.9 percent. German GDP has only increased by 5 percent. Unlike Germany, the U.K. has so far also managed to avoid recession. Far from a reduction in trade, Britain has seen a boom in exports, especially in the service sector, since withdrawing from the EU trade block. Service exports grew by nearly 18 percent in real terms from 2016 to 2022—the strongest growth in this sector among the G7 countries, according to OECD data, and far more than in neighbors such as Italy, Germany, and France.

In any case, Nelson posed the Mississippi Question nearly two years before Britain voted to leave the EU. The country’s lackluster output, productivity, and growth were apparent long before Brexit. Leaving the EU should have been a perfect opportunity to correct course, but little has been done to address the problem. In fact, after leaving the EU, Britain has been hit by a succession of disastrous policy choices.

Having rushed to impose a lockdown in the early stages of the coronavirus pandemic, British ministers insisted on ever more draconian measures long after it was apparent that such steps were disproportionate, as well as ruinously expensive. Then, in the name of achieving Net Zero targets on “decarbonizing” the U.K. economy by 2050, successive governments have made rash commitments to move to renewables. Higher energy costs have helped price British industry out of world markets.

Instead of changing course, ministers have stuck stubbornly to their dogma—even though the latest moves to outlaw the internal combustion engine and new emissions regulations are making car ownership unaffordable for millions.

Mississippi has managed to borrow good ideas proven to work elsewhere. Britain, by contrast, has preferred to pioneer its own bad ideas. The former approach helps explains why Mississippi is emerging as part of a wider southern success story. The latter approach accounts for why a once successful country is really struggling.

“Woke” radicals love to undermine America at every opportunity. They try to rewrite history in order to demoralize and disorientate the United States.

Cultural Marxism is able to thrive in that vacuum where there was once good civics education. If we want to defeat the radicals, both on and off campus, there are six things we should ensure every American child understands.

1. America is built on liberty.

Liberty is what makes America special. This country was started in 1776 because people living in 13 former British colonies had had enough of being bossed about by a British king.

America today might have its fair share of busybody politicians and bureaucrats, but the default setting in this country is to distrust anyone claiming authority over others, from George III to Dr. Fauci.

Americans also dislike being told what to think, and particularly having their children told what to think: an extraordinary 3.7 million American schoolchildren are now homeschooled.

2. The US Constitution created the best system of government in the world.

America might only be 240-something years old, but the US Constitution is now the oldest written Constitution in the world (with the exception of tiny San Marino). For context, France, which had its revolution at about the same time as America, is now on its fifth constitution. (Incidentally, how's that working out?)

It might be fashionable for CNN pundits to proclaim that American democracy is in crisis, but it is nonsense. If and when Americans adhere to what the Founders actually wrote, the system works.

The document they drafted, which fuses English ideas about natural rights with recently rediscovered insights from republican Rome, has withstood the test of time – and the challenge from would-be tyrants.

3. America is a force for good.

No country is perfect, and America has had its fair share of blunders. But overall, America has been a force for good in the world.

All previous great powers used their might to establish empires. Far from subjugating people, the United States used her strength to set people free, insisting the European powers dismantle their empires.

On three occasions – World War I, World War II and the Cold War - the United States has intervened to save the free world. Can you imagine what the world today would be like if on any of those occasions, the other side had won?

4. Americans are amazingly inventive.

From the first flight of the Kitty Hawk to the advent of the iPhone, there is one country that has proved extraordinarily inventive; the United States.

Take a look at the everyday household objects around you as you read this. The light bulb. The microwave oven. The refrigerator. Toothpaste. All are American inventions.

Innovation depends on being able to try out new things. It means freedom to fail. America is inventive because she is free.

5. Judeo-Christian ideals have shaped America.

Religion has been remarkably important in shaping America. Yes, I know that the Founders kept religion and government separate. That was not because they thought religion unimportant but in fact the opposite.

The Founders wanted to avoid the oppression of smaller religious groups, as had happened in Europe.

When George Washington became President, he wrote an extraordinary letter to the Jewish congregation in Newport, Rhode Island. In it, he made it clear that they had a right to follow their faith. No one needed anyone else’s approval to worship as they pleased.

America’s emphasis on individualism is, I suspect, a reflection of Judeo-Christian thinking.

6. Americans have so much to be thankful for.

“Woke” ideology encourages grievance and resentment, rather than gratitude. This is why the “woke” seldom seem happy.

Gratitude is an essential ingredient for happiness – and if you want to “pursue happiness” won’t get very far without appreciating the good things that you have.

It is not a coincidence that one of the most important days in the American calendar is called “Thanksgiving”.

Initially, a day to show gratitude for getting the harvest in, today Thanksgiving is a day to celebrate being American. Simply being an American means you have so much to be thankful for.