Life on this side of the pond is far from perfect. Politics is deeply divisive. Gun crime is off the charts: more people get shot in the course of a year in one small city here in Mississippi than in the whole of London.

It baffles me that no one in America seems capable of making a decent cup of tea. I’m puzzled that a country so technologically proficient as the United States does not seem to be able to do roundabouts.

But there are, without question, some things that America does rather well.

Low taxes

A middle class family earning $50,000 a year in this part of America would expect to pay about 15 per cent in federal and state taxes. In the UK, they would be taxed almost a quarter of what they earned.

It is difficult to make an exact comparison, since the amount of tax people pay varies state by state, but overall, the tax burden here is far lower.

Higher living standards

Americans tend to live well. GDP per person in the UK is about $45,000: in America, it’s around $70,000. American workers are vastly more productive than those in Europe, Britain or almost anyplace else.

I constantly marvel at how blue collar America is better off than much of white collar Britain. Materially, everything is more bountiful, from the cars and the boats to the houses and the hair-dos.

Customer service

It is striking how enthusiastic ordinary Americans are about the jobs they do, and nowhere more so than when it comes to customer service. Perhaps it has something to do with the prevalence of tipping, which incentivises that can-do service culture. Maybe it also has something to do with the fact that so many Americans will take on some kind of customer service job to get through college.

Whatever the reason, there is seldom the sort of surly attitude often encountered in other parts of the world.

Liberty

America does liberty better than anyone. It might be the instinct of politicians in every country to boss us about, but in America the default is to distrust any would-be autocrat. This country founded in rebellion against a King has a long tradition of scepticism towards anyone claiming authority over the people, from George III to Dr Fauci.

That is not to say that America does not have its fair share of busybody mayors and governors, especially along the east and west coasts. But across much of the vast American heartland, however, ordinary folk often simply refuse to be told what to do. Americans also dislike being told what to think, and particularly having their children told what to think: an extraordinary 3.7 million American school children have now been kept out of the government run school system by their families and are educated by home schooling networks.

Health care

In Britain, where the National Health Service has become a kind of national religion, it is deemed sacrilegious to imply that any other country might have better health care. To suggest that Americans might have better health outcomes puts you beyond the pale.

But the facts speak for themselves. If you are going to fall seriously ill, you would be better off being ill on the US side of the Atlantic. According to the World Population Review, you would be nearly twice as likely to survive lung cancer in America (18.7 per cent survival rate) as in the UK (9.6 per cent survival). If you get breast cancer, you have an almost nine in ten chance of surviving in America. In Britain, it’s only 81 per cent. Some 97 per cent of prostate cancer patients survive in the US: in the UK, it’s only 83 percent.

There’s more to it than survival rates: a friend of mine was recently admitted to hospital for a minor operation. When I asked about the ward he was on, no one understood what I was talking about since every patient had their own room.

Manners

Americans tend to have remarkably good manners. It’s not just the polite way in which they greet strangers: Americans, especially in the South, have an old fashioned etiquette that we Brits once had but seem to have lost along the way.

I am constantly impressed with the good manners of young Americans in particular. At a football game I went to recently, there was lots of shouting, plenty of passionate yelling. The crowd made it brutally clear when they disagreed with the referees’ decision. Yet I did not hear a single F word the entire afternoon.

Local democracy

Everyone seems to have an opinion about American politics, perhaps especially people that don’t live here. All that attention, however, is mostly focused on what is happening at the federal level: the local nature of American democracy is often overlooked.

The United States should be thought of not as a backdrop to the political drama taking place in Washington DC, but a mosaic of self-governing communities, detached from what happens in the national capital.

Most of the key public policy decisions in America are decided at the state level. Key fiscal decisions are made at county level. A myriad of different officials, from sheriff to tax collector, are elected by local people in the communities they serve. This system of local democracy in America largely works in a way that local government in Britain since the days of Ted Heath has not.

This article was originally featured in The Telegraph.

What comes to mind when you think of Mississippi? Steamboats on the river? Mississippi mud pie, maybe? Does America’s Deep South conjure up images of cotton fields and backwoods poverty, full of folk who subsist on God, guns and grits? You might be surprised to learn that Mississippi, the poorest state in the US, is now wealthier than Britain.

Mississippi’s GDP per capita last year was $47,190, slightly above the UK’s approximately $45,000, though still well below the overall American average of $70,000. While the UK’s per capita GDP has stagnated for the past 15 years, Mississippi’s has been rising rapidly to the point that it has just overtaken us.

For decades Mississippi was in the doldrums and median household income was low. It was the poster child for US deprivation, home to catfish, cotton, a spot of forestry and little else in the way of economic activity.

Three years ago I moved to Jackson to run a free-market think tank, the Mississippi Center for Public Policy. I made the move after 12 years as the MP for Clacton-on-Sea in Essex, first as a Conservative and then as Ukip’s first elected MP, after I left the Tory party and won a by-election. Brexit was why I went into politics, and in 2020, we left the EU.

Why did I then come to Mississippi? I came because I saw a great opportunity to achieve change.

Over the past 40 years, those southern US states that have embraced free-market reforms, such as Texas, Tennessee and Florida, have done remarkably well. Helping Mississippi adopt similar reforms would almost guarantee something similar. Frustrated by the inability of those who run Britain to change much for the better, I was attracted to America.

In the US there is an appetite for improvement, and those you vote for — especially at the state level — have the power to deliver it. That is why Mississippi is now overtaking Britain. In recent years the state has used its freedom to make bold free-market reforms. Last year it introduced the largest tax cut in its history, slashing income tax to a flat 4 per cent from 2026. Only a dozen or so US states have a lower personal tax burden. An average middle-class family with a household salary of $50,000 might pay total federal and state income taxes in the region of 15 per cent, or $7,676. In the UK, the equivalent rate would be 23 per cent.

For years the nepotistic “good ol’ boy” system handed out public sector jobs that were often comfortable sinecures. Now, in Mississippi, politicians compete to reduce the size of the public payroll. Ten years ago there were 649 public employees for every 10,000 people in the state. Today it’s down to 606 per 10,000. Thanks to these and other reforms, Mississippi is starting to prosper, with per capita income up 25 per cent over the past five years. In Britain, real wages and living standards have not grown since 2007.

Life is far from perfect, of course, and there is still plenty of inequality: 31 per cent of black residents live in poverty. Unemployment levels in the state are similar to those in the UK — about 3.5 per cent — but black unemployment is higher at 5.7 per cent. Nonetheless, attitudes have changed beyond recognition — for the better.

What my time in Mississippi has made abundantly clear to me is that the kind of change that has brought about such sharp improvements here in recent years simply isn’t possible in Britain today. Brexit, for heaven’s sake, was nearly nullified by Britain’s administrative state — and that had a direct democratic mandate from millions. What chance is there of any lesser reforms being let through without a revolutionary change in the way Britain is governed?

Until a leader emerges prepared to take on the obstructive mandarinate the way Margaret Thatcher took on and destroyed the National Union of Mineworkers, politics will remain stylised posturing and not much more. Britain could learn a thing or two from Mississippi.

This article was originally published in The Times.

The company offers 98 flavours, all of them too obnoxious to swallow

July 4 is a big deal in America. People here don’t merely celebrate the day that thirteen former British colonies broke away from Britain back in 1776. Americans, I discovered when I moved here, spend July 4 revelling in being American. No matter when it was that you or your ancestors moved over here, July 4 is an occasion to rejoice that they did.

So, it is hard to overstate how offensive it was for Ben & Jerry’s, the ice cream vendor, to mark the day with a tweet claiming that “the US exists on stolen Indigenous land”, which should be “returned”.

What possessed Ben & Jerry’s, part of the global Unilever conglomerate, to say something quite so gratuitously offensive?

Ben & Jerry’s are not only guilty of bad history (Indigenous American tribes were busy “stealing” from other indigenous Americans long before the Mayflower showed up). They are guilty of hypocrisy.

While attacking America for existing on “stolen land”, their parent company, Unilever, sells ice cream to Putin’s Russia, a country that is actually engaged in stealing bits of Ukraine.

Unilever says it is still operating in Russia because “for companies like Unilever, which have a significant physical presence in the country, exiting is not straightforward” and because “were we to abandon our business and brands in the country, they would be appropriated – and then operated – by the Russian state”.

And both the ice-cream company and its eponymous founder Ben Cohen have such a dislike of free Western society that they have been guilty of blaming Putin’s opponents for his murderous, atrocity-laden war, rather than him. “You cannot simultaneously prevent and prepare for war,” the company’s social-media mouthpieces tweeted as the crisis intensified early last year, no doubt causing students of Vegetius and George Washington to roll their eyes.

“We call on President Biden to de-escalate tensions and work for peace rather than prepare for war,” the virtue-signalling corporate spokespersons went on.

“Sending thousands more US troops to Europe in response to Russia’s threats against Ukraine only fans the flame of war.”

Cohen for his part has helped pay for a full-page ad in the New York Times which blamed Putin’s invasion on “deliberate provocations” by the US and Nato. He has also funded a “journalism” prize that praised its winner for exposing “Washington’s true objectives in the Ukraine war, such as urging regime change in Russia.”

It’s not just Ben & Jerry’s. Earlier this year, Bud Light, one of America’s top beer brands, decided it was time to distance the brand from its “frat guy” customers and embrace transgender “inclusivity”. Before that, Disney, a leading family entertainment business, made a big deal of backing a radical stance on social issues.

As Vivek Ramaswamy, a potential future Vice President of the United States, has been energetically pointing out, many of America’s leading fund managers impose explicitly “woke” agenda on the businesses they invest in. And of course, we have seen plenty of evidence of “woke” finance in the UK this week when it emerged that Coutts Bank closed the account of Nigel Farage, a leading Brexiteer and climate change sceptic, because he did not have the right “values”.

What we once called “political correctness” has long been evident on American university campuses. But until relatively recently, that’s where it stayed. Now these ideas are moving mainstream.

When a big corporation indulges in “woke” signalling, it’s easy to assume that they know what they are doing. When Bud Light decided to embrace transgenderism, I imagined it was all part of a cunning marketing plan by clever MBAs to sell more beer.

But “woke” ideas seep into boardrooms and marketing departments that are otherwise bereft of intelligent insights. Look at some of the consequences.

Bud Light’s marketing campaign offended their core customer base, and sales fell by about a third. Disney’s share price fell significantly. Far from protecting Coutts’ reputation, the bank’s decision to close Farage’s account has been a huge blow to its image.

It is time for consumers to start boycotting Unilever brands the way they have stopped buying Bud. There are plenty of less obnoxious alternatives to Ben & Jerry’s.

“Woke” people adopted that term to describe themselves because they see themselves as having “woken up” to the unjust ways of the world. They believe that they have a heightened sense of social injustice that others lack.

From this comes a sense of moral superiority which causes intelligent and highly educated people to make remarkably stupid decisions.

If being “woke” is bad business, why does it keep happening? We are seeing the consequences of two decades of having “woke” HR departments across corporate America.

For years, big firms have been recruiting and promoting people on the basis of diversity and inclusion – or even their commitment to combating climate change. An organization that recruits and promotes people on the basis of anything other than competence at their actual job risks becoming incompetent. A lot of fairly mediocre people have been overpromoted to the point where their mediocrity is starting to stand out.

We are starting to see a long overdue correction: and it would be a good thing if Ben & Jerry’s took the same kind of hit that Bud Light did.

Douglas Carswell is the President & CEO of the Mississippi Center for Public Policy.

This article was originally featured in The Telegraph.

I love hearing good news about Mississippi. When I read recently that there had been an improvement in education standards in our state, I was thrilled.

But then I looked at the data. The claims being made that there has been a ‘Mississippi miracle’ are not, sadly, substantiated by the facts.

Claims of a big improvement in literacy performance are based on National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) scores for 4th graders. These show that between 2019 and 2022, Mississippi moved up the national rankings, from 29th to 21st.

But when you look at the actual scores, the average reading score for a 4th grader in 2019 was 219. By 2022 the average reading score for a 4th grader had fallen slightly to 217. Far from improving, the scores went down.

The reason Mississippi appeared to rise up the rankings is because reading performance for 4th graders in other states fell even faster.

If you look more at the same data set, it turns out that only one in three 4th graders in 2022 were proficient in reading. A similar number are at or below basic level reading. I would not call that a ‘miracle’.

Those 4th graders tested in 2022 had had to endure almost two years of Covid lockdown disruptions, often having to be absent from the classroom. Despite that, the average score fell just 2 points. What does that say about the added value of being in a classroom?

As for the NAEP results for math, between 2019 and 2022, average 4th-grade scores in our state fell from 241 to 234. In other words, there was both an absolute and relative fall in performance. NAEP scores for 4th graders are only one way to measure education outcomes. Another benchmark is the ACT scores, which look at how students are performing at the end of 11th grade. The facts show falling proficiency, with an average ACT composite of 18.3 in Mississippi in 2016 falling to an average ACT composite of 17.4 in 2022. Again, these are the indisputable facts.

There are only four school board districts in the entire state in which the ACT composite score had not fallen over those six years.

Mississippi also uses state student performance scores from a variety of assessments to calculate reading and math proficiency. For the first time in more than two decades, the cumulative scores in 2022 for reading and math proficiency in Mississippi school districts appeared to show improvement. A sign of progress? Not really.

The apparent uptick in district proficiency scores between 2016 and 2022 in math and reading reflects the fact that in 2022 they stopped including end-of-course testing for seniors. The year before that change was made, there was no evidence of an improvement in standards.

The ‘progress’ in these state scores and consequential decline in the number of F-rated school districts is almost entirely a reflection of eliminating the end-of-course tests for seniors which raised proficiency percentages and increased the graduation rate.

If performance has not in fact improved, why might education bureaucrats and campaign organizations want us to believe that there had been progress? You only need to ask the question to answer it.

Doctoring data to sustain a fictitious narrative about improving education standards does our state a grave disservice.

Back in the old Soviet Union, local officials use to annually report record levels of agricultural output and an extraordinary increase in the number of tractors produced. Was this proof that the system was working? Quite the opposite. No one wanted to be the one not to report record rises. It did not pay to challenge the dodgy data.

The education system in Mississippi is not working either. It is deeply disingenuous to claim improvements in performance when the data shows a decline. Those making these claims must know the truth, but they chose to gloss over it. Mississippi deserves better than that.

Education progress is possible when the vested interests that run public education are no longer able to run the system in their interests. Progress will only come about when families in our state are given control over their child’s education tax dollars – as is about to happen in Arkansas.

The sooner people realize the truth about education standards in our state, the sooner they will demand parental power to put it right. The vested interests know that which is why they aren’t being honest with you.

The Mississippi Charter School Authorizer Board approved a potential new charter’s application for a final review last week. While we are excited to see the possibility of a new charter school opening in our state, we know that there could be so many more currently operating if it weren’t for the board’s continuous roadblocks.

Clarksdale Collegiate Prep, which is wanting to extend its existing K-8 charter school to grades 9-12, met all of the necessary criteria for the second stage of the charter school approval process – an evaluation to ensure the quality of the school meets the board’s standards. It met the Stage 1 requirements, the application completion check, earlier this year and will move on to Stage 3, an independent evaluation team review, for final authorization.

However, the Authorizer Board denied the Stage 2 application for Level-Up Academy, which would have created a K-5 charter school in Greenville. The board cited funding concerns, implying the enrollment projections would not produce enough revenue to operate.

This is not the first time the Authorizer Board has denied applications for charter schools in Mississippi.

When the Mississippi Legislature enacted the “Mississippi Charter Schools Act of 2013,” many hoped there would be a multitude of charter schools opening across the state as a way to give Mississippi children alternative options for their education. But this hasn’t been the case.

According to a report published last year, from 2014-2021, there have been 56 charter school applications submitted, not including the dozens of other letters of intent for potential charters. Of those 56 applications, only 8 were authorized for operation. That’s a 14% acceptance rate.

While some applications may have contained credible evidence for denial, the majority of flaws found in these applications were minor. It’s nearly impossible for any piece of writing to be perfect, let alone a 400-page document.

The stated mission of the Mississippi Charter School Authorizer Board is to authorize high-quality charter schools that will expand opportunities for underserved students in our state. Its job should be to work with applicants to ensure they are acceptable, not block applications that aren’t 100% perfect.

According to Magnolia Tribune, charter school students in Mississippi perform at the same level or even better than traditional public school students. Considering the fact that Mississippi’s charter school law requires charter schools to only operate in failing school districts, this shows charters are making a difference in many children’s educational journeys.

Mississippi First conducted a survey a few years ago, with results showing that over 75% of parents in charter school communities support charter schools and almost 100% of parents are satisfied with the academic progress of their children.

The data shows that charter schools are helping Mississippi children. No one is requiring students to attend charter schools, but those who want to should be able to do so. But with the board’s continuous disapproval rate, fewer children have that option.

It’s time the Authorizer Board began seeing the bigger picture, rather than the insignificant details that won’t necessarily affect a school’s performance, operation or sustainability.

It’s time the board stood by its declared mission – to authorize charter schools in order to expand opportunities for Mississippi children, not deny them.

I recently came across an old McDonald’s menu from the early 2000s. A Quarter Pounder cost $2.29. A regular shake $1.69. Large fries $1.59.

Today, you would need to pay about twice that. Two decades of inflation – particularly in the past three years - means that a dollar buys much less than it did back then.

We are all familiar with the idea that prices rise over time. Ever since the US Federal Reserve broke the link between the US dollar and gold in August 1971, inflation has become a permanent part of life.

If, however, we measure price changes in constant dollar amounts (what economists call “real terms”), or if you consider how long it might take someone on the median income to earn enough to buy something, we can get a much more accurate picture of how prices have changed.

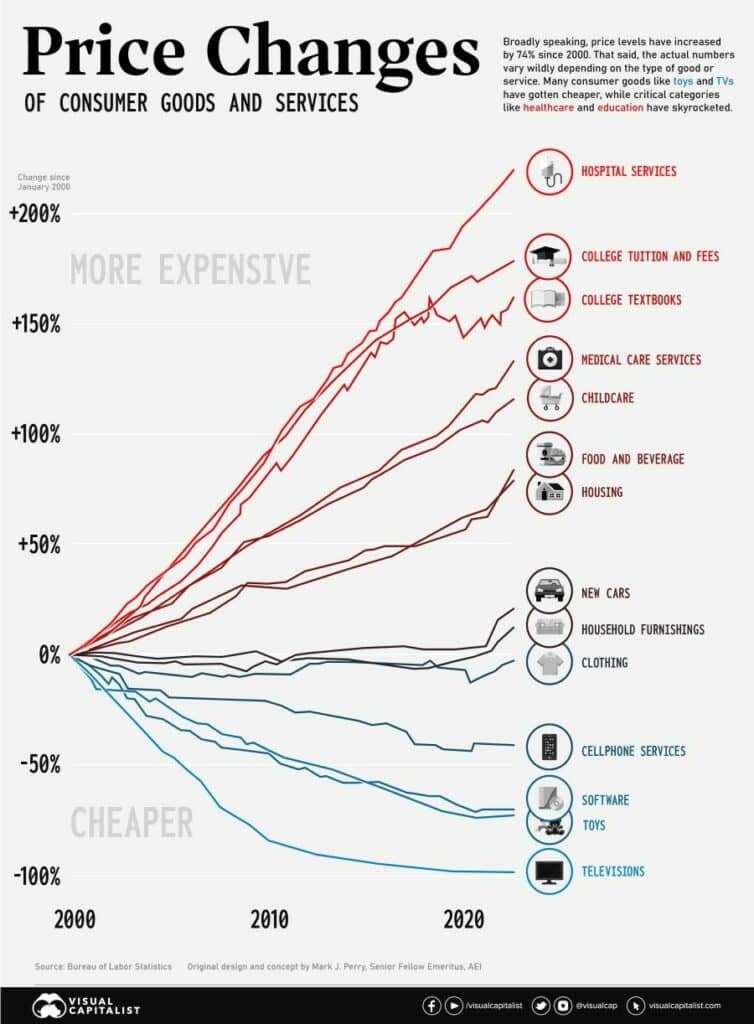

The chart above from Visual Capitalist shows how the price of various consumer items has changed since the start of the century.

US households get a far better deal when they buy toys, televisions or cellular services than was the case twenty years ago. The price of TVs in real terms has plummeted. A large flat-screen TV in 2000, according to VisualCapitalist, cost about 17 percent of median income. Today? Less than 1 percent of (a much higher) median income.

That’s the good news, but the bad news is that the price of other items has skyrocketed whichever way you measure it. Over the past two decades, the price of hospital services has risen over 200 percent. College tuition is up almost 170 percent.

Why have the costs of some things fallen so dramatically, but the costs of others risen?

Anyone wanting to sell you cellular services, or a TV, or toys in America today is operating in a fiercely competitive market. They are under constant pressure to give customers a good deal.

At the same time, companies in those sectors often operate globally, meaning that they benefit from the advantages of international trade, and can then pass those gains on to their customers.

What about the healthcare economy or higher education? There simply aren’t the incentives for providers in those sectors to give customers a better deal.

Not only is there less competition in these sectors, but they are protected by government regulation and barriers to entry that intentionally keep out the competition.

Here in Mississippi, for example, in order to provide a new healthcare facility, a provider will usually have to get a permit – called a Certificate of Need. Since these permits usually require the approval of existing healthcare providers, they are notoriously difficult to obtain.

Prices are determined via costly negotiations with insurance companies, rather than by pressure to keep giving customers a better deal.

A good rule of thumb is that prices have fallen whenever there is choice and competition, and government regulation is limited. Where there is lots of government regulation, prices have soared.

No one in Washington, as far as I know, has yet come up with a plan to make televisions or toys more affordable. Yet that is what the current administration is proposing to do for healthcare and higher education when they propose more Medicaid and student loan cancellation.

Ironic, isn’t it? Having made healthcare and higher education insanely expensive through regulation, government then comes along with an offer to make them more affordable to some.

What we ought to do instead is to abolish Certificate of Need laws and incentivize providers to offer customers, not just insurance companies, a better deal.

Rules on university tenure need to go, so that instead of running colleges for the convenience of those on the payroll, they are run in the best interests of those that save desperately in order to be able to afford to graduate. We also need to change the law on university accreditation so that there is less box ticking about diversity and inclusion, and more emphasis on how a degree actually adds value for students.

If there was a free market in healthcare and higher education, the cost of both would come down. If we don’t deregulate either sector, prices will continue to rise.

Talking of excessive regulation keeping out the competition, I was dismayed to hear that this week the Mississippi Charter School Authorizer Board only approved a single new Charter School in 2023.

This means that a decade since Charter Schools were allowed under Mississippi law, we have a grand total of eight. Our Authorizer Board has been cheerfully rejecting more applications than it has approved to the point that I think it is a minor miracle that anyone bothers to apply at all.

If Mississippi had an Authorizer Board for fast food outlets, McDonald’s Quarter Pounders would be an expensive luxury. The only way our state will see a significant increase in Charter Schools is if we actually appoint people to run the Authorizer Board that believe in school choice.

Douglas Carswell is the President & CEO of the Mississippi Center for Public Policy.

For decades, many US universities were solid bastions of academic excellence, producing well-rounded citizens. Then suddenly, wham! They’re embroiled in a row about white privilege and the need to make reparations for the past.

What we once called “political correctness” has been a thing on certain progressive university campuses since the 1980s. But until relatively recently, extreme ideas more or less stayed there. Now it feels as if these radical ideas are moving mainstream.

Last week, as millions of Americans celebrated July 4th, Ben & Jerry’s ice cream (owned by the international corporation, Unilever) put out a tweet claiming that the United States "exists on stolen land," which should be "returned."

Not long before that, one of Bud Light’s marketing executives talked about the need to distance the brand from "frat guys," and embrace "inclusivity." Their campaign certainly seems to have cost them the "frat guys," without perhaps including as many new transgender customers. Reports suggest they lost about a third of their sales. Not long before that, there was Disney, a leading family entertainment business in America, which decided to take a radical stance on social issues in Florida that many families might object to.

Espousing “woke” ideas might enable a certain sort of not-very-bright academic to appear cleverer than they actually are. But why indulge these ideas in the world of business? What possesses an established company to suddenly embrace an ideological stance almost designed to offend millions of potential customers?

Initially, I assumed that it was all part of a cunning marketing plan. Now I wonder if it is arrogance coupled with a blind adherence to ideology.

To understand why some people go woke, perhaps we should try to understand something about the nature of the “woke” belief system in the first place.

Those that are “woke” are called “woke” because they see themselves as having woken up to the way that the world actually works – hence the name. According to their self-image, they have a heightened awareness of social injustice. So much so, in fact, that they have an understanding of the world around them that others do not have.

A defining characteristic of being “woke” is to have a sense of moral superiority over those that are unwoke. It is this sense of moral superiority, I believe, rather than any carefully thought-through marketing campaign, which explains why some marketing executives run such gratuitous campaigns.

“Woke” ideology is really a belief system, rather like a religion. Indeed, for many of its adherents, “woke” ideology has become a kind of post-religious religion. "When a man stops believing in God," wrote GK Chesterton, "he doesn’t then believe in nothing, he believes anything." For the past half-century, there has been a decline in traditional religious observance throughout the Western world. The cult of woke has come along as the belief system for those who no longer believe.

“Woke” ideas give people a way of making sense of the world - however absurd it might seem to the rest of us. “Woke” ideology places everyone into a hierarchy of victimhood. Those with certain immutable characteristics are deemed "oppressors," and those with others are deemed the "oppressed." It is your so-called “intersectional identity” that determines where you sit in the hierarchy of victimhood – and fundamentally, your moral worth.

Once you see the world this way, politics ceases to be a matter of personal preference or opinion. Instead, it becomes a choice between absolute right Vs absolute wrong. Marketing ceases to be a matter of trying to maximize sales and revenue. It becomes a chance to demonstrate your absolute righteousness, even at the expense of telling your customers they are bad.

Saddest of all, those that join the cult of woke all too often stop seeing friends and family as an assortment of people, with mixed tastes and opinions, bound by love. Instead, those that are not part of the cult of inclusivity and tolerance must be cut off.

If the “woke” creed resembles a religion, it is one that does not seem to offer much hope of redemption. Those that fall short get canceled.

According to the cult of woke, socioeconomic outcomes in America are not explained by differences in individual aptitude or behavior. They are explained by the unfairness of "the system," which the “woke” believe is inherently immoral and wrong.

Once you start to see the world that way, you don’t just start to believe that America is always in the wrong. Like every bloody revolutionary from the Jacobins to the Leninists, you start to believe that you need to tear down what exists and start again.

“Woke” ideas are not merely an annoyance or an irritation. They are a profoundly malevolent belief system that unless tackled, risk tearing the American Republic apart.

It is encouraging that we are starting to see consumer boycotts against “woke” corporations, but we need to see much more of it. I have been impressed with Vivek Ramaswamy’s campaign against “woke” investment managers on Wall Street. This could be the start of something big.

Here at the Mississippi Center for Public Policy, we run a Leadership Academy designed as an antidote to "woke." We introduce young Mississippians to the idea that the free market and America are a force for moral good. We teach classes on why the United States is a profoundly moral achievement, and why Americans should take pride in their country and its (imperfect) past.

If we are to develop an effective antidote to the “woke” delusion, perhaps we must also recognize that human beings need to believe in something bigger and better than themselves. If we do not offer them a good and true belief system, they will latch on to one that is malevolent and false.

Douglas Carswell is the President & CEO of the Mississippi Center for Public Policy.

What was the most significant thing Donald Trump did as President?

Love him or loathe him, Trump’s Supreme Court appointments look like they might have been the most consequential thing he did in office. Of the nine Justices on the Court, one third of them - Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett - are Trump appointees.

Trump’s trio have decisively changed the balance of opinion on the Court – and the implications of this only seem to grow.

The Supreme Court recently ruled that ‘affirmative action’ cannot be used as part of a university admissions process. Or to be more precise, it ruled that the system used by Harvard University and the University of North Carolina, does not comply with the principles of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment or the protections of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act.

For decades, universities have used race-based preferencing to rig their selection systems in favor of some racial groups, and at the expense of others. Often this has meant universities admitting more African American students, with lower grades, than they otherwise might have, and at the expense of Asian American students with higher grades.

In the words of Justice Clarence Thomas, “all forms of discrimination based on race — including so-called affirmative action — are prohibited under the Constitution”.

Progressive academics, hooked on ‘woke’ ideology as an addict is to meth, may deviously look to circumvent the ruling. Regardless, an important victory has been won by those who believe that the way to end racial discrimination is to stop racially discriminating.

So-called ‘affirmative action’ can now be challenged in the knowledge that the Supreme Court will likely rule against it should ‘woke’ bureaucrats be daft enough to let things go far. Let the litigation begin …. Perhaps we will now see a flurry of cases aimed at overturning ‘affirmative action’ when it comes to awarding public procurement contracts and practices within local government?

A day later, the Supreme Court made another momentous decision, when it ruled that President Biden’s plan to cancel over $400 billion of student loan debt was also contrary to the Constitution. A few hours after that, the Court ruled that a Christian website designer could not be compelled by state law in Colorado to articulate views that they did not themselves endorse.

A year before, the Court famously overturned Roe Vs Wade, ruling that decisions about abortion should be left to each individual state.

Maybe the Court’s most consequential ruling of all is one that has received the least attention. Last summer, the Court ruled that the Environment Protection Agency did not have the power it presumed to have. For the first time since the New Deal, the legal assumptions that have allowed for the aggrandizement of the administrative state are being challenged.

Responding to the Court’s recent ruling on affirmative action, President Biden declared that ‘this is not a normal court’. He’s right.

The norm, since the Warren court of the 1950s, has been to have the Supreme Court adjudicate on the basis of what the judges would like the law to say. Today, we have a Supreme Court ruling on the basis of what the law actually says. So accustomed have we become after decades of judicial activism that might not feel normal, but it is what the Founders intended.

Back in the 1980s, Ronald Reagan attempted to change things, selecting the brilliant Robert Bork to sit on the Court - only to have him rejected by Congress after a bruising battle. Something similar almost happened when Bush the elder appointed Clarence Thomas. He had to endure a smear campaign similar to what Brett Kavanaugh experienced more recently.

Some characterize the change in the composition of the Court as a tilt towards conservatism after years of leaning liberal. I am not sure that is quite right. Recent Court rulings on election law in Alabama and Louisiana certainly weren’t welcomed by many conservatives in those states.

What the Supreme Court seems to have done is move away from judicial activism in favor of originalism – the idea that they should stay true to the original intentions of the Founders when they drafted the Constitution.

Perhaps that’s one bias the Supreme Court should always have.

Mississippi was hit by epic thunderstorms the other week. Like thousands of other people across the state, perhaps you were left without electricity?

For me, no electricity meant trying to work without air-conditioning. Not having any AC was not a productive experience. As I sweltered in the heat, I was left wondering how people in Mississippi managed before the advent of AC?

Invented in 1902 by Willis Carrier, within living memory, there were plenty of homes and offices in Mississippi that did not have any AC. For a start, it was once very expensive. According to the website HumanProgress.org, the cost of AC units has fallen by 97 percent since the early 1950s. AC only became ubiquitous in cars and shops within the past two or three decades.

Imagine what life would be like in Mississippi without refrigeration? As late as the 1950s, that was how a significant number of people in our state lived.

When the first self-contained refrigerator, the Frigidaire, went on sale in 1919 it cost $775 – or about $12,000 in today’s money. Today, you can buy a vastly better refrigerator for only a fraction of the cost.

It’s not only the costs of keeping cool that have come down.

In 1979, to buy a 14-inch television, the average American earning the average wage would have needed to work 70 hours to earn enough. Today, a vastly better TV can be purchased for the equivalent of 4 hours of work.

The other day I re-watched Wall Street, that classic 1980s movie starring Michael Douglas as Gordon Gekko. In the movie, Gekko uses one of the first commercial cell phones, a DynaTec. Apparently, Gekko’s phone retailed for almost $4,000 at the time, or over $10,000 in today’s prices. It needed re-charging after 30 minutes.

Today, even someone on the minimum wage in Mississippi could afford a vastly better cell phone than anything available to Wall Street billionaires a generation ago.

Among those officially classified as ‘poor’ in America, 99 percent live in homes that have a fridge, 95 percent have a television, 88 percent have a phone and over 70 percent own a car.

1996, the real cost of household appliances has fallen by over 40 percent. The cost of footwear and clothes by 60 percent. Indeed, the average American home is full of gadgets, entertainment systems and labor-saving devices many of which had not even been invented when Ronald Reagan was in the White House.

As my friend the author, Matt Ridley puts it, “Our generation has access to more calories, watts, horsepower, gigabytes, megahertz, square feet, air miles, food per acre, miles per gallon, and, of course, money than any who lived before us”.

And here’s another remarkable thing. We get all this extra stuff without having to work as hard. In 1913, the average American worker put in 1,036 hours that year, compared to less than 750 hours a year now.

Often, I hear people talking about there being ‘too much technology’. It is fashionable to say that we should turn away from technology and get back to a pure and simple past. Really? I’ve heard anyone express that sort of opinion in the poor places, such as Uganda or Kenya, that I’ve lived in. If anyone ever tells you that we have too much technology, you might want to suggest that they switch off the air-conditioning for a few hours and think about it.

Thank goodness for modern technology – and the free market that makes it available at an affordable price for everyone.

Douglas Carswell is the President & CEO of the Mississippi Center for Public Policy.