Few people would argue with the beauty of a California sunset. The bright lights of Times Square are tough to compete with. But there is one thing that can top the allure of California or Manhattan: your pocketbook.

While many on the left may argue that a certain class of Americans enjoy the high-tax, high-regulation burdens of our most liberal cities and states, and the perceived protections that go with it, the numbers paint a different picture.

Americans are moving to lower tax states where they are able to keep more of the money they earn. This isn’t a talking point, but a statistical reality based on migration data. Unfortunately, Mississippi is on the wrong side of both taxes and, as a result, in-migration.

Sales, property, and individual income taxes, as a percentage of personal income in Mississippi, are 9.9 percent, according to Cato Institute. That’s pretty high. In fact, only 14 states, including traditional high tax states like California, Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York, fared worse. All neighboring states had lower tax burdens than Mississippi. What effect does this have?

Mississippi had a net migration loss of over 3,500 in 2016. On a per capita basis, this means Mississippi lost 100 residents for every 88 the state gained. This is parallel with migration loses in Louisiana. Alabama and Arkansas were essentially flat in terms of migration while Tennessee added over 13,000 residents. For every 100 residents that Tennessee lost, they added 119.

Tennessee, a state without an individual income tax, is home to one of the lowest tax rates in the country with a tax burden of 6.5 percent. And they are reaping the benefits of smart fiscal policy. The Wall Street Journal reported in May: “Alliance-Bernstein Holding LP plans to relocate its headquarters, chief executive and most of its New York staff to Nashville, Tenn., in an attempt to cut costs…In a memo to employees, Alliance-Bernstein cited lower state, city and property taxes compared with the New York metropolitan area among the reasons for the relocation. Nashville’s affordable cost of living, shorter commutes and ability to draw talent were other factors.”

Twenty-six states had a tax burden of 8.5 percent or greater. Of those 26, 25 had a net out-migration. Only Maine was able to buck the trend. And not surprisingly, of the 17 states that had net migration gains in 2016, all but one has a tax burden of less than 8.5 percent. All totaled, more than 500,000 individuals moved from the top 25 highest-tax states to the 25 lowest-tax states in 2016. Those high tax states lost an aggregate income of $33 billion.

Along with the relatively high individual tax burden, our business tax climate sits at 31st best, according to the Tax Foundation. Not terrible, and actually better than Alabama, Arkansas, and Louisiana, but not great either. The same report had Tennessee at 16.

So what can we do in Mississippi? We can follow the lead of high-growth, low-tax states in the Southeast that have lower taxes, lighter licensure and regulatory burdens, and a smaller government.

This past session, the legislature debated a bill known as the “Brain Drain” Tax Credit. It would have provided a three-year income-tax exemption to recent college graduates who are Mississippi residents. And there was an additional two-year exemption for those who start a business. It passed the House unanimously but died in the Senate without a vote.

States are in competition with one another. We know this because we routinely offer incentives for select companies in the form of subsidies or tax breaks, or we propose eliminating the individual income tax for three to five years for recent college graduates.

While we are always in favor of lower taxes, these moves are just an acknowledgement that our tax burden hurts individual opportunity and the state’s economic growth. We have succeeded in phasing out the lowest income tax bracket. Instead of eliminating the income tax for just a few, we should work on eliminating the income tax for all taxpayers. And instead of offering incentives to just a few, our goal should be to create the most business-friendly climate in the country – for all types, sizes, and industries.

A public policy based on freedom is the recipe high-growth states have adopted. It’s how we’ll grow our economy in Mississippi, too.

This column appeared in the Daily Leader on October 31, 2018.

Mississippi’s freedom ranking moved up a couple spots from the previous year while our overall score actually declined slightly.

Fraser Institute’s “Economic Freedom of North America 2018” again paints a relatively bleak picture for economic freedom in Mississippi. Mississippi has been included among the “Least Free” states, those in the bottom quartile, for all but two years going back to 1998.

“The freest economies operate with minimal government interference, relying upon personal choice and markets to answer basic economic questions such as what is to be produced, how it is to be produced, how much is produced, and for whom production is intended. As government imposes restrictions on these choices, there is less economic freedom,” the report writes.

The data is reviewed among three categories: government spending, taxes, and regulations.

What are these categories important? As the size of government expands, the private sector becomes smaller and is slowly pushed out with government choosing to undertake activities beyond the traditional function of a limited government. As our tax burden and regulations grow, restrictions on private choice increase and economic freedom declines. Mississippi continues to have serious issues in both categories.

And we know what the analysis shows: The freer the state, the more prosperous it is. And the more it is growing in terms of in-migration. The least free, the more people are likely to be leaving in searching of better prospects.

...

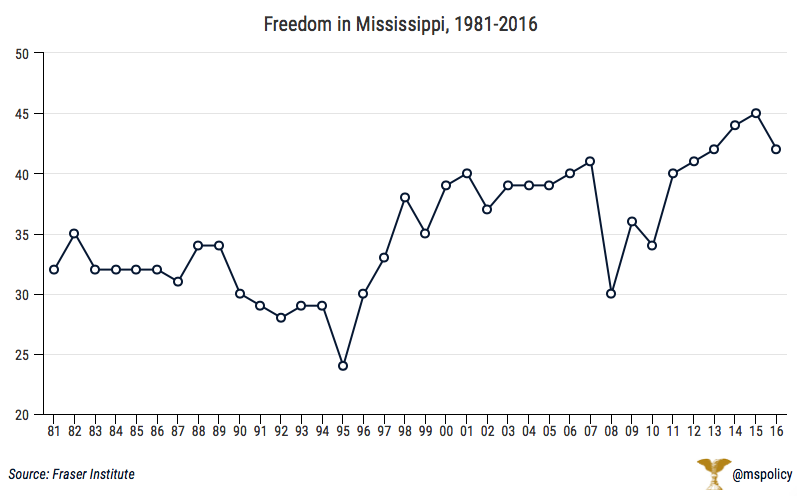

Though Mississippi saw a slight improvement this year in overall rankings, the state has been on the wrong path over the life of the report. When it began in 1981, Mississippi was ranked 32nd. There have been some ups-and-downs along the way, including a peak at 24th in 1995. But overall, the numbers aren’t positive. The ranking of 45th that was released last year was the lowest the state has ever been.

Going back to 1981 and for many years after that, Mississippi did much better in the government spending and taxes categories than the numbers show today. That year, Mississippi had a government spending score of 7.01 and a taxes score of 6.75. This year those scores are 4.25 and 5.85, respectively. Regulations have shown the most positive movement, from 2.27 to 5.23, though still lower than all but seven states.

In 1981, Mississippi earned a score of 5.34. This year it’s 5.11. Only two other states, Kentucky and New Mexico, have experienced decreases from 1981.

….

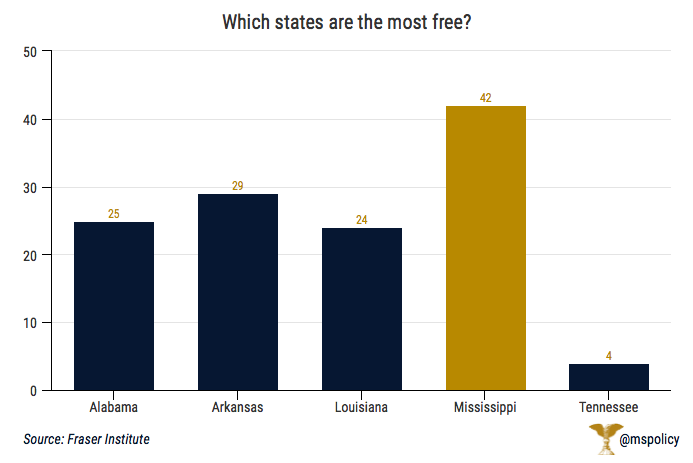

Mississippi performed poorly compared to all neighboring states, and much of the Southeast. Alabama had an overall score of 6.22 (25th), Arkansas had a score of 6.09 (29th), Louisiana had a score of 6.26 (24th), and Tennessee had a score of 7.43 (4th). Those numbers put Tennessee among the most free, placed Alabama and Louisiana in the second quartile, with Arkansas in the third quartile.

When it comes to promoting policies that restrict freedom, Mississippi is sitting on an island. And, unfortunately, paying the price.

….

Overall, this data isn’t far off from a recent report from Cato Institute. Their report, “Freedom in the Fifty States,” put Mississippi 40th overall. A five-spot jump from 2014, but still in the bottom 20 percent.

Some positive trends, but still a long way to go.

As children in Mississippi and around the country prepare for a night of trick-or-treating, they may unknowingly run afoul with local laws.

These aren’t laws restricting criminal actions often associated with Halloween mischief, such as egging a house or smashing pumpkins that belong to someone else. Rather, these are restrictions on who can trick-or-treat, how late they can be out, and what they can or can’t wear.

A story on Roanoke, Virginia’s trick-or-treating laws went viral earlier this month. In Roanoke, no one over 12 is allowed to trick-or-treat. Not only is it illegal, it is a misdemeanor punishable by up to six months in jail.

While the potential jail time might not apply, the city of Meridian also prohibits those over 12 from asking for candy. “It shall be unlawful for any person to appear on the streets, highways, public homes, private homes, or public places in the city to make trick or treat visitations; except, that this section shall not apply to children 12 years old and under on Halloween night,” the ordinance reads. And you have to be inside by 8 p.m.

Throughout the country, towns like Belville, Illinois, Bishopville, South Carolina, and Boonsboro, Maryland have similar age limits.

Meridian also restricts anyone over 12 from wearing a mask or any other disguise, unless they get a permission slip from the mayor or chief of police. Dublin, Georgia and Walnut Creek, California have similar mask restrictions.

The rest of your costume may also be illegal in some locales. In Alabama, it’s illegal to dress up as a minister, priest, nun, or any other member of clergy. Violators can be slapped with a $500 fine and a year in jail.

In a recent move that received national attention, the Kemper County Board of Supervisors approved a measure in 2016 that made it illegal for anyone to appear in public in a clown costume or clown makeup for Halloween that year. The ordinance expired the day after Halloween. That ordinance carried a fine of $150 for outlaws who wore clown costumes.

The conventional wisdom is that these ordinances aren’t enforced. Police aren’t asking boys who are starting to show signs of facial hair for identification to check their age. Chances are no one is spending 365 days in a county jail in Alabama for impersonating a priest or rabbi.

Which, of course, leads to the next question: Why have such laws? We already have laws on the books to restrict actual criminal activity. We don’t need additional laws that are confusing and do little but potentially ruin a fun night for millions of children.

We simply have too many laws in this country. It should not be government’s responsibility to regulate the behavior of children on a Halloween night running through the neighborhood in pursuit of treats. That responsibility belongs to the parents, just like it should on every other night of the year.

Mississippi Center for Public Policy recently added their name in support of the First Step Act.

The First Step Act will provide meaningful reform to our criminal justice system at the federal level, similar to what we have experienced in Mississippi. We know from a long history of being one of the nation’s top incarcerators that the blunt instrument of a long sentence does little to improve the conditions of our state’s communities.

The research shows that locking up low-level offenders does not produce better public safety outcomes than effective probation tools and workforce partnerships. We also know that time in prison breaks family bonds and makes it next to impossible for a person to hold down a job. That’s a bad outcome for all of us. Instead, we should be using what we know works to move people out of the system and toward productive, law-abiding lives.

Over the past three years, Mississippi has enacted a number of key reforms. During this time, the prison population has declined by more than 10 percent, driven by a reduction in prison use for non-violent offenses. At the same time, our state’s prisons are more focused on violent offenders, who now occupy 63 percent of prison beds, as opposed to 56 percent prior to reform. Today, the property crime rate has decreased by 5 percent, while violent crime has remained at a historic low.

Mississippi, like many other states, has seen the benefits of smart criminal justice reform policies. We are confident similar results can be found at the federal level.

Read the full letter to Senator Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) here.

Food truck regulations around the country continue to be challenged in court because they are indefensible from a legal perspective.

If Tupelo leaders continue to try to regulate these businesses in an effort to protect the brick and mortar restaurants, it is very likely the same scenario will play out in the city that gave us Elvis. The constitution specifically prohibits such economic protectionism. Our legal arm, the Mississippi Justice Institute, has already cautioned the City Council against such actions.

Rather than making the case by leveraging the consequences of a legal challenge, I would like to appeal to the leaders of Tupelo to consider the practical reasons why being on the side of economic liberty is the prudent choice. This is not a partisan issue. It is an issue of free enterprise, consumer choice, and the proper role of government in a system of capitalism.

It is not the role of government to protect any business, brick and mortar or otherwise, from competition. The free enterprise system operates correctly when consumer choice, not political blessing, is the basis of choosing the winners and losers.

From a practical standpoint, it is also a mistake to thwart a powerful economic trend like food trucks. These businesses are examples of entrepreneurs responding to market signals. In so doing, they are contributing to the local economy by serving a customer niche. Brick and mortar restaurant entrepreneurs can do the same, and many have. All of these entrepreneurs, new and old, are creating unique options and that work to build a more diverse and appealing food marketplace in Tupelo. In turn, this attracts more consumers to the downtown – creating a bigger, healthier and more prosperous local economy.

In a properly functioning economy in America, the success of a food company should be based on how good the food and service is; not on how well connected it is to the political class. In a system of capitalism, competitors respond to consumer trends with innovations and improved offerings, not by seeking government help to build a moat around their businesses. We should be encouraging entrepreneurs and risk-takers, not creating hurdles out of a misplaced sense of obligation to protect existing businesses.

In many ways, the food truck controversy is similar to those disputes we’ve seen around the country where local governments are determining how to regulate Airbnb and Uber. Rather than government looking to create new and restrictive regulations for these emerging businesses, they should be thinking about how to reduce the existing regulatory burdens on brick and mortar restaurants and hotels. The local economy would be the beneficiary of such actions and no one would argue against a policy that spurs economic growth – especially not in a state where we have struggled to experience sustainable growth in our private sector.

On behalf of customers, competition, and consumer choice, I hope this appeal to the political leaders of Tupelo does not land on deaf ears. Cites across the country are realizing these kinds of cases are very hard to defend. However, the City Council should not vote to keep the regulatory burden for food trucks low out of a fear of the legal consequences; they should do it because it’s in the best economic interests of Tupelo.

This column appeared in the Daily Journal on October 28, 2018.

The EPA and the Department of Transportation have been working together for the past year to create a new set of standards for the automotive industry. The goal is to use a lighter regulatory hand and a more consumer-friendly approach to address the burdensome and wildly expensive standards mandated during the Obama administration.

The 2012 CAFÉ (Corporate Average Fuel Economy) standard went well beyond a rational approach in the name of the environment.

Americans should have the freedom to decide what kind of car they drive, not bureaucrats in Washington or California. Choosing that car and producing cars that meet those needs does not mean that Americans, or the companies that produce their cars, are not concerned about the environment. We can do both. We can balance social, environmental, and economic impacts.

The proposed new standards, called SAFE (Safe Affordable Fuel Efficient Autos) are a smart and reasonable approach to keeping cars affordable while also ensuring increased fuel efficiency and improved emissions. The CAFÉ standard went beyond boundaries allowed by the Clean Air Act and basically doubled the fuel efficiency standards for American vehicles - mandating new cars have an average fuel efficiency of 54.5 MPG by 2025.

For many citizens, car ownership isn’t a luxury; it’s a lifeline. Creating reasonable and balanced automotive standards will have a positive impact on millions of Americans and thousands of Mississippians who rely on their cars every single day. It’s time we let consumers decide what kind of car to drive, not unelected bureaucrats in Sacramento.

At the Mississippi Center for Public Policy, we support the SAFE standards for four main reasons:

- We believe automakers should design vehicles to meet the choices of consumers, not to meet the preferences of bureaucrats.

- We believe no state should get to dictate the kinds of cars another state’s citizens can or should drive. To California, we say, “You sweep your porch and we’ll sweep ours.”

- We believe the CAFÉ mandates were based on a world of energy scarcity, not the world of energy abundance in which we live today.

- We believe if left unchanged, the current standards would significantly increase the average cost of a vehicle and provide an unnecessary burden on many Mississippians – even pricing some consumers entirely out of the new car market. This would increase safety risks for some and could also prove to be a drag on the automotive industry – an important part of the Mississippi economy.

For additional reading on the proposed reforms, check out this article: https://thehill.com/opinion/energy-environment/409512-unreasonable-demands-stifle-real-environmental-progress

Over the past 20 years, the price of a college education has increased nearly 200 percent.

These numbers, adjusted for inflation, trail only the cost of hospital services when it comes to changes in the prices of consumer goods and services. During the same period, inflation stands at 55 percent.

What about other items? The price of housing has increased at about the rate of inflation. But consumer goods such as cars, household furnishings, clothing, cellphone service, software, toys, and TVs are all cheaper today than they were in 1997. In some instances, the prices have decreased significantly.

So why have the prices of some items decreased? And why have some, college education in particular, become more expensive? As with most items that have become more expensive, we can largely thank the government.

It’s the law of unintended consequences that we often see with federal legislation. A prime example is the “Great Society” of the 1960s. As we grew the welfare state as a nation, out-of-wedlock birth rates increased from about 5 percent fifty-years-ago to over 40 percent today. In Mississippi, it’s 53 percent. As a result, we have generations of children who grew up without Dad, leading to numerous negative societal effects.

The Americans with Disabilities Act, or ADA, is another example of unintended consequences. Designed to lower barriers to employment for disabled persons, research shows that the law has actually harmed employment opportunities for those who are disabled. Prior to the law, 60 out of every 100 disabled men were able to find jobs. Thanks to the bad incentives created by the law, the number fell to 50 per 100 disabled men after the ADA went into effect.

In an effort to make college more affordable, government involvement has only made college more expensive. Because of readily available financial aid, there are no market mechanisms to control for costs. While those in the private sector have incentives to constantly innovate and maintain competitive costs, there is no such need in higher education. After all, when tuition goes up at Ole Miss, it also goes up at Mississippi State. The schools see no benefit to lower costs. If a school wants to raise tuition, the money to attend will be there - courtesy of Washington, D.C.

Unfortunately, that money isn’t just going toward educational purposes. The ballooning costs of a four-year education are funding new administrators and non-teaching sprawl on campus. Indeed, universities now employ more administrators than faculty members. And as part of an education arms race on non-education services, we constantly see new and improved cafeterias, student unions, recreation centers, climbing walls, and other things today’s students apparently need in today’s university experience.

As prices climb, students, and their families, don’t really notice it. At least, not at the time. Because most students are just taking out loans and money is going directly from the federal government to the office at a university that handles student account payments, the student never feels the pain of writing a large check.

And as the federal money flowed, we watched a dramatic change. The missions of colleges and universities shifted from teaching and preparing students to use critical thinking and particular skills to start a successful career to preparing students for a future in political correctness, being constantly offended, and progressive indoctrination.

We’ve seen campuses shift from a place where rigorous intellectual debate, along with civility and decorum, is the norm to one in which conservative speakers are routinely shouted down and even shut down, simply because some students don’t like their message or feel offended by speech with which they disagree. Sadly, administrators are often complicit in this censoring, if not supportive of the protesting actions.

Most recently, a sociology professor at Ole Miss, James Thomas, made national news when he encouraged protestors to “put your whole fingers in their salads” and to “bring boxes and take their food home.” Because, as Thomas put it, “They (Republicans) don’t deserve your civility.” This came on the heels of liberal activists confronting and harassing Republican Senators while they were dining out.

If we want to make college affordable and return higher education to the respected and noble status it once held, we must end federal subsidies to colleges and universities. For more than a century, the American university system was considered the best in the world for providing a classical liberal undergraduate education. Our federal government has jeopardized that.

For the sake of our future generations, we’ve got to reclaim our public colleges.

This column appeared in the Madison County Journal on September 25, 2018.

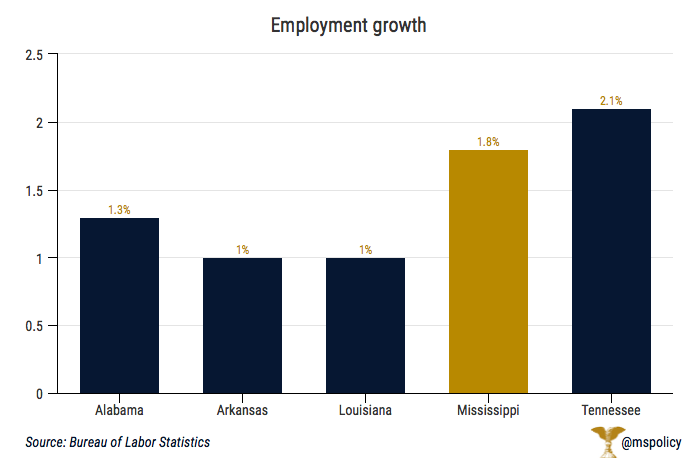

Mississippi payrolls have added more than 20,000 jobs over the past year with employment numbers setting a new record.

According to the most recent data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are now 1.17 million people in the state working. That’s a boost from a little less than 1.15 million a year ago. This is a statistically significant employment change of 1.8 percent. Only Tennessee, who saw a 2.1 percent growth, posted better numbers among neighboring states.

Alabama’s employment grew by 1.3 percent, while employment grew by 1 percent in Arkansas and Louisiana.

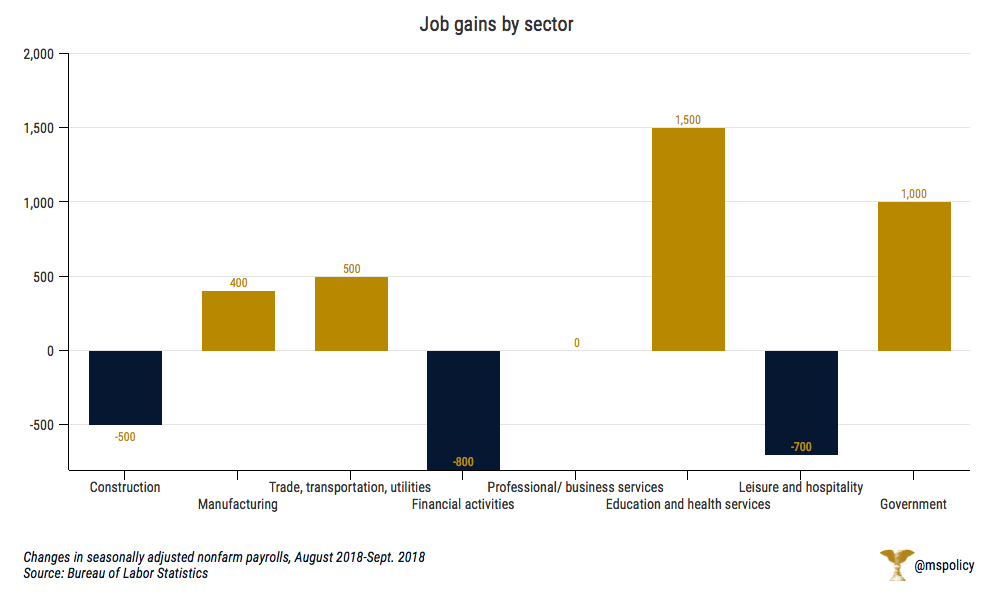

Mississippi added jobs in four sectors over the past month. The largest gains were in education and health services (+1,500 jobs) and government (+1,000 jobs). Manufacturing and trade, transportation, and utilities posted slight gains, while professional and business services growth was flat. Construction, financial activities, and leisure and hospitality showed loses over the past month.

Over the past year, construction (-200) is the only sector to post a decrease in employment. The largest gainer over the past year was professional and business services (+6,400).

Mississippi has also seen a large gain in the public sector, particularly over the past three months. Government has added 2,800 jobs over the past year with 1,600 jobs added alone in the past quarter. Government jobs account for 14 percent of the jobs created in Mississippi over the past year. This is significant because a growing public sector can often stifle the growth of the private sector.

In this measurement, Mississippi far outpaced our neighbors. Louisiana’s government was down 200 jobs last month. Arkansas’s government did not change and Tennessee added 100 government jobs between August and September. Alabama’s government added 300 jobs last month.

Mississippi’s unemployment rate remained steady at 4.8 percent. That is a near record low for the state, but is still the fourth highest in the nation. Only Louisiana, at 5 percent, has a higher rate in the Southeast.

The city of Tupelo appears to have backed away from controversial regulations that would have prohibited food trucks from most high-traffic areas in the city.

But some city leaders continue their push for protections for brick-and-mortar restaurants at the expense of food truck operators.

During Monday’s work session, the city released the proposed regulations. According to the Daily Journal, this includes additional licensure and some limitations on parking but lacks the restrictions on setting up on Main and Gloster Streets, the two most prominent retails areas in the city, as originally discussed.

“We have not been protectionist and made any distance requirements between competing business,” Ben Logan, city attorney said.

Mayor Jason Shelton, a Democrat, added, “I want to be pro-business,” Shelton said. “I don’t think we need more restrictions on businesses. I think we need to look at restrictions to take away.”

New regulations have been in the works for some time now, with support for restrictions from both Democrats and Republicans.

Earlier this year, Councilman Willie Jennings said, in proposing the regulations, “I just want to make sure the established businesses are protected.” Another councilman, Markel Whittington, said brick-and-mortar restaurants have requested food truck regulations. While he didn’t feel food trucks posed a ‘threat’ to those restaurants, he believed it was appropriate for government to act ‘on behalf of select business interests.’

“I think we have to protect some of our taxpayers and high employers,” he said.

And even yesterday, Councilman Mike Bryan lobbied for brick-and-mortar restaurant protections, such as a ban on major roads. Another councilman, Buddy Palmer, also indicated his support for a ban.

“I feel like it is not fair to brick-and-mortar businesses to allow food trucks to park in front of their business,” Bryan said.

“I will always be pro-downtown businesses over food trucks,” Palmer said. “I am for brick-and-mortar businesses much more than I am for food trucks.”

When Tupelo leaders began discussing food truck regulations, Mississippi Justice Institute, the legal arm of Mississippi Center for Public Policy, sent a letter to the city warning of litigation if these regulations passed.

“The very regulation Tupelo is discussing—a regulation about how close a food truck should be to a restaurant—was found to be unenforceable just this past December in Baltimore. Food truck regulations around the country have been challenged over and over in court, from Louisville, to San Antonio, to Chicago, and many places in between. Cities ultimately realize that these kinds of cases are very hard to defend,” the letter said.

More recently, the city of Carolina Beach, North Carolina repealed its prohibition on out-of-town food trucks from serving the city after a lawsuit was filed by the Institute of Justice. Under the law that has since been scrapped, only brick-and-mortar restaurants that have been in business for more than one year could run a food truck.

“It is a shame that it took a lawsuit to convince the town to repeal such an obviously unconstitutional law,” Justin Pearson, senior attorney at IJ said. “I’m hopeful that this vote will signal the end to the town’s attempt to use the power of government to favor a handful of established businesses over the region’s entrepreneurs.”