Moody’s Investors Services has revised the outlook for the state of Mississippi from negative to stable.

They also affirmed the Aa2 ratings on outstanding GO bonds and the Aa3 ratings on debt issued from the Mississippi Development Bank.

“The state's stable outlook, which applies to its GO as well as its appropriation debt, is supported by stabilization of revenue and economic trends and a resumption of deposits to the rainy day fund,” Moody’s wrote. “The outlook also incorporates the expected continuance of conservative fiscal management, which will help manage elevated debt levels and potential future revenue weakness.”

To see a future upgrade, Moody’s said Mississippi needs:

- Growth in state wealth levels reflecting a sustained progress trending to national average

- Sustained increase in fund balance

- Substantial decrease in debt and pension liabilities

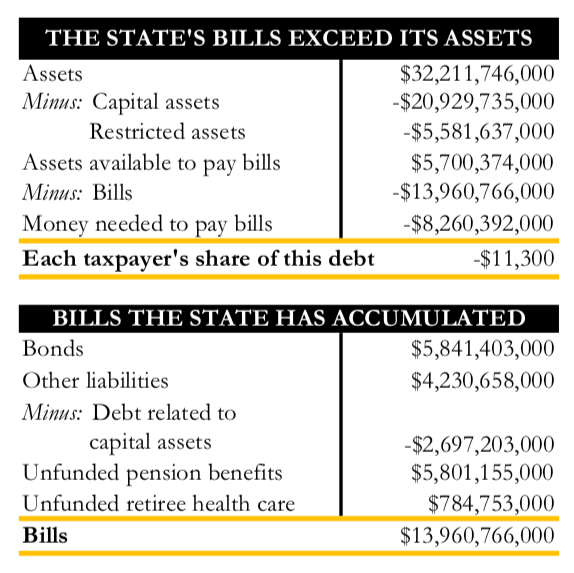

Pension liabilities are a major issue for the state, as they are for most states. A recent report from Truth In Accounting noted Mississippi’s unfunded retirement obligations. And because of the state’s debt burden of $8.3 billion, each taxpayer has a burden of $11,300.

In September, S&P Global Ratings similarly revised the state’s general obligation debt outlook from negative to stable.

“Now, all three of Mississippi’s credit ratings are strong and positive,” said Treasurer Lynn Fitch. “Taxpayers will benefit from recent efforts to meet economic challenges head-on, such as putting money back into the Rainy Day Fund and strengthening PERS’ funding policy. Better ratings mean the bond issuances currently in the works for capital and transportation improvements across the State will yield better deals for taxpayers.”

A depletion of financial reserves, economic underperformances, and persistent growth in retiree benefit liabilities could lead to a future downgrade.

A new analysis of financial reports gives Mississippi a “D” for the state’s fiscal health.

According to the report from Truth In Accounting, Mississippi’s finances were ranked 33rd among the 50 states. Based on money available, each taxpayer would have to pay $11,300 to cover the state’s bill.

A large part of that problem is due to retirement obligations for state workers.

“Mississippi's elected officials have made repeated financial decisions that have left the state with a debt burden of $8.3 billion, according to the analysis. That burden equates to $11,300 for every state taxpayer. Mississippi's financial problems stem mostly from unfunded retirement obligations that have accumulated over many years. Of the $16 billion in retirement benefits promised, the state has not funded $5.8 billion in pension and $784.8 million in retiree health care benefits,” the report notes.

The report shows:

- Mississippi has $5.7 billion available in assets to pay $14 billion worth of bills.

- The outcome is a $8.3 billion shortfall and a $11,300 Taxpayer Burden.

- Despite reporting all of its pension debt, the state continues to hide $596.4 million of its retiree health care debt.

- Mississippi's reported net position is inflated by $1.4 billion, largely because the state defers recognizing losses incurred when the net pension liability increases.

A specific breakdown of assets and bills.

“Mississippi's financial condition is not only alarming but also misleading as government officials have failed to disclose significant amounts of retirement debt on the state’s balance sheet,” the report continues. “Residents and taxpayers have been presented with an unreliable and inaccurate accounting of the state government’s finances.”

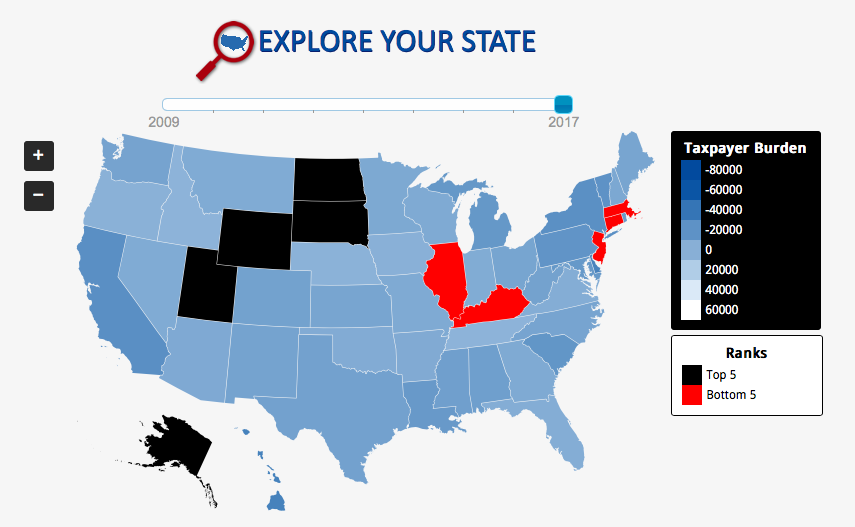

The taxpayer burden in Mississippi is down slightly from the past two years when it was $11,800 (2015) and $11,900 (2016). However, just nine years ago the burden was only $4,900 per resident.

Louisiana had the worst taxpayer burden among Mississippi’s neighbors at $15,500 per resident. Alabama was similar to Mississippi at $11,800 while Arkansas had a burden of $3,600 per resident.

Tennessee was in the best position, earning a B from Truth in Accounting, with a $2,500 taxpayer surplus. Nine years ago, Tennessee had a $600 taxpayer burden. But they have been steadily moving in the right direction and have been in the black for the past six years.

New Jersey had the greatest burden at more than $61,000 per resident. Alaska had the strongest surplus, $56,500 per resident.

The Mississippi Bureau of Narcotics has begun to return property that the agency seized after the administrative forfeiture law was repealed.

This past session, the Mississippi legislature allowed the administrative forfeiture provision to sunset, meaning the previous law ceased to be in effect at the end of June. Administrative forfeiture allows agents of the state to take property valued under $20,000 and forfeit it by merely providing the individual with a notice. An individual would then have to file a petition in court to appeal.

On September 19, 2018, MBN sent notices allowing retrieval of seized property, totaling more than $100,000, to eight individuals. This includes:

- $3,757 of seized currency to Courtney Walker of Biloxi

- $3,000 of seized currency and two rifles to Michael Willis of Cyrstal Springs

- $88,737 of sized currency to Luis Medeles and Christopher Zavala, both of Brownsville, Texas

- $1,860 of seized currency to Dewayne Spearman of Pontotoc

- $11,938 of seized currency to Tejinder Kaur of Brandon

- $2,300 of seized currency and a pistol to Dexter Danzel Conner of Tuscaloosa, Ala.

- A seized handgun and a holster to Jessica Meredith of Florence

On September 10, the Mississippi Justice Institute sent a letter to MBN advising the agency of the change in the law after it became apparent that they were continuing to seize property after the July 1 repeal date.

“We are glad to see that the Mississippi Bureau of Narcotics is not only following the law, but is taking corrective action in cases where administrative forfeiture procedures were incorrectly used,” said Aaron Rice, Director of the Mississippi Justice Institute. “As a public interest law firm dedicated to ensuring that our laws are carried out in a way that protects liberty and honors constitutional rights, we are happy to have been able to assist MBN in carrying out its duties while remaining in compliance with new changes in Mississippi law.”

Until 2017, Mississippi was the wild west of sorts when it came to civil asset forfeiture. In 2015, the Mississippi Bureau of Narcotics, along with local police departments, seized nearly $4 million in cash.

They seized amounts as low as $75. They seized trucks, cars, ATVs, riding lawnmowers, utility trailers, and 18-wheelers; an arsenal of assorted handguns, shotguns, and rifles; cell phones, cameras, laptops, tablets, turntables, and flat screen TVs; boat motors, weed eaters, and power drills; and one comic book collection, according to a report from Reason.

And that does not include numbers from police departments that work independently of the Bureau of Narcotics. Until 2017, they didn’t track or publish asset forfeiture data.

Moreover, family members, especially parents, often had their cars or other property seized for the alleged crimes of their children. This happened even though the parents are not connected to the illegal activity. For example, in 2015, the Desoto County Sheriff’s Department agreed to return a 2006 Chevy Trailblazer owned by the mother of the petitioner, Jesse Smith, in exchange for $1,650.

In 2017, the legislature provided needed reforms. Now, seizing agencies must obtain a search warrant issued by a judge within 72 hours of seizing property. And all forfeitures are posted on a publicly accessible website.

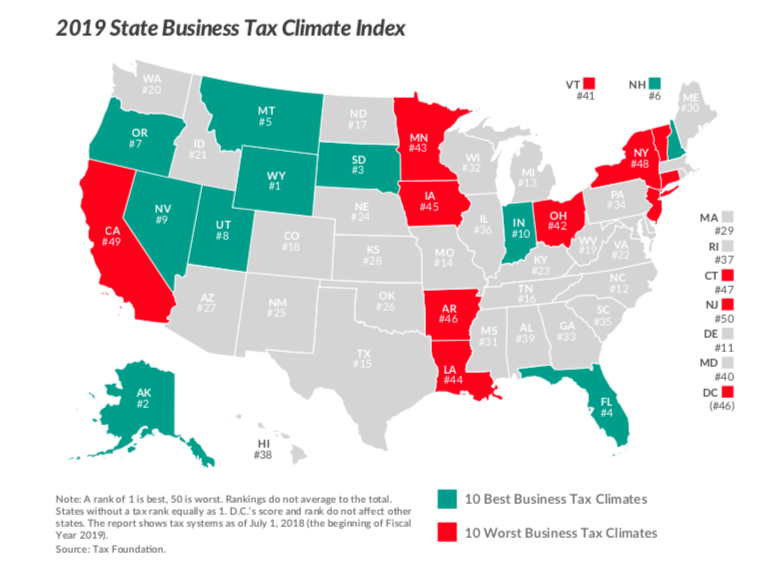

Mississippi’s business tax climate rating dropped slightly over the past year.

The Tax Foundation’s “State Business Tax Climate Index” grades each state on the burden of their corporate taxes, individual income taxes, sales taxes, property taxes, and unemployment insurance taxes. Fewer policy areas are as important as tax policy when it comes to economic growth.

The five highest rated states were Wyoming, Alaska, South Dakota, Florida, and Montana, while the five worst states in terms of business tax climate were New Jersey, California, New York, Connecticut, and Arkansas.

Mississippi’s ranking isn’t that much different from where it has been the past four years, ranging from a high of 29 (in 2016 and last year) to a low of 31 (this year). In 2017, the state ranked 30th. Still, Mississippi did drop slightly from the previous year.

This change, however, isn’t due to negative action taken by the state but simply because other states had passed Mississippi. One of those was Kentucky, the biggest gainer nationwide. They moved up 16 spots from 39th to 23rd after a series of tax reforms in the Bluegrass State.

Compared to our neighbors, Tennessee is doing the best by far. The income-tax-free state was rated 16th. Mississippi, however, bested our three other border states: Alabama (39), Louisiana (44), and Arkansas (46). That is good, but not anything to necessarily celebrate as it says more about their poor-performance.

Looking within the different tax categories, Mississippi did best with respect to unemployment insurance taxes (5) and corporate taxes (15). In fact, the corporate taxes topped all neighboring states, including Tennessee. However, Mississippi’s rankings for individual taxes (27), sales taxes (35), and property taxes (36) held the state back.

Generally speaking, the states with the best business tax climate are also the states that having a growing economy and a growing population.

A school district in Mississippi appears to have backtracked from comments that appeared in a recent article detailing the district’s new proposed policy for homeschool students.

According to the Delta Democrat Times, Greenville Public School District Deputy Superintendent Glenn Dedeaux said the district is “legally responsible to ensure every child of educating age receives an adequate education” and he warned that not all homeschool curricula “are approved by the Mississippi Department of Education to meet the necessary standards.”

Dedeaux also implied that homeschoolers must take subject matter tests to graduate.

Regardless of what you may or may not think about homeschooling, these comments run counter to Mississippi law. Indeed, Mississippi has one of the most parent-friendly homeschool laws in the country.

Mississippi code specifically says:

[I]t is not the intention of this section to impair the primary right and the obligation of the parent . . . to choose the proper education and training” for their child, “and nothing in this section shall ever be construed to grant, by implication or otherwise, to the State of Mississippi . . . any right or authority to control, manage, supervise or make any suggestion as to the control, management or supervision” of the private education of children. Further, “this section shall never be construed so as to grant, by implication or otherwise, any right or authority to any state agency or other entity to control, manage, supervise, provide for or affect the operation, management, program, curriculum, admissions policy or discipline of any such school or home instruction program.

To homeschool in Mississippi, a family must file a certificate of enrollment with the school attendance officer where the family resides. They must do this by September 15. Beyond that, parents have the freedom to make their own education decisions for their children.

While there is not official data on the number of homeschoolers in Mississippi, estimates put it at around 17,000 students statewide. If homeschoolers were a single district, they would be the fourth largest district in the state.

Dan Beasley, an attorney with the Home School Legal Defense Association, reached out to Dedeaux. Dedeaux said he was misquoted in the original article. And, to his credit, he understands he has no authority over which program a homeschool family selects.

Mississippi families who choose to homeschool their children should not be susceptible to illegal attempts by school districts to regulate their education.

A government boycott of a company for an exercise of free speech would be a flagrant violation of the First Amendment.

Chick-fil-A has been heavily criticized for its reputation as a supporter of traditional marriage. The company’s CEO has made public comments in support of traditional marriage, and the company has donated money to organizations that opposed same-sex marriage before the Supreme Court ruled on the issue.

While it is Chick-Fil-A’s constitutional right to engage in free speech, liberal government officials around the country could not stand it. When Chick-Fil-A attempted to re-open a franchise at the Denver International Airport, the city council saw its opportunity for retribution.

Councilman Paul Lopez called his opposition to allowing the chain at the airport “really, truly a moral issue on the city.” “We can do better than this brand in Denver at our airport, in my estimation,” another member Jolon Clark said.

The problem was that Chick-Fil-A’s speech was protected by the First Amendment, which meant the government could not punish the company in retaliation for its speech. The Denver officials had made it abundantly clear that their opposition to allowing Chick-Fil-A into the airport was due to their personal objection to Chick-Fil-A’s speech. Because of this, the city was ultimately forced to allow the chain into the airport.

You don’t have to be a constitutional scholar to understand that this exclusion would have been a violation of the First Amendment. It doesn’t even pass the smell test. If something like this happened in Mississippi, many citizens would be outraged. Rightfully so.

But this is happening in Mississippi right now, just not to Chick-Fil-A. Instead, Nike has drawn the ire of the Mississippi Department of Public Safety (MDPS) for its new ad campaign featuring former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick, who is widely known for sparking a protest movement in professional sports where players kneel during the national anthem.

The MDPS commissioner recently announced to the Associated Press that MDPS will no longer purchase training equipment from Nike.

Like the Denver officials, the MDPS commissioner made clear that his decision to initiate a government boycott was based on his personal objection to the speech made by Nike, saying: “As commissioner of the Department of Public Safety, I will not support vendors who do not support law enforcement and our military.”

The commissioner’s views are understandable and well-intentioned. He is a Navy veteran and a long serving law enforcement officer. He appears to feel strongly about this issue.

As a proud American myself, and as a fellow military veteran who lost a leg in Iraq, I would not personally choose the national anthem as a venue for protest as Kaepernick has, or to highlight this act as Nike has. However, I fought to protect their right to do just that without fear of government retribution, and I am always heartened to see citizens actually exercising that right.

Moreover, the Mississippi Center for Public Policy, of which the Mississippi Justice Institute is a division, has clearly communicated, on several occasions, its opposition to using the national anthem as a venue to protest at sporting events.

But this issue is not about the commissioner’s views or my views on Nike’s speech, or the identity politics which would elevate our views above those of others based on our status as veterans. It is about the Constitution that we have both sworn to protect.

A government boycott of Nike is simply unconstitutional.

Here is the tricky thing about the Constitution: it works both ways. If you stand by and watch its protections erode while your adversaries’ rights are under assault, you can’t be shocked when its protections are not there for you when the tables are turned. If you don’t want a government boycott of Tim Tebow’s kneeling, you can’t defend a government boycott of Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling.

A government boycott in retaliation for corporate speech also ignores Mississippi law establishing bidding requirements for most public purchases. We have those laws for a reason.

Lastly, conducting a government boycott is simply not the proper role of government. A public official boycotting vendors with certain views implies that taxpayer money is their money, to reward or punish whom they see fit based on their own personal beliefs. Many Mississippians may agree strongly with the vendor’s message, and other Mississippians may oppose it. The government should not use public funds to attempt to speak for all taxpaying Mississippians on matters of public discourse.

If a public official wants to personally boycott a company in response to its speech, they are free to do that and the First Amendment protects that right for them. But when acting in their official capacity using taxpayer money, neither the Constitution, nor Mississippi law, nor a healthy respect for the opinions of their fellow Mississippians allow for such personal indulgences.

The Mississippi Justice Institute has requested the commissioner to rescind his government boycott. We trust he will uphold our Constitution.

This column appeared in the Clarion Ledger on September 28, 2018.

In this edition of Freedom Minute, we talk about why a government boycott based upon a personal objection to speech made by a company is unconstitutional.

The Mississippi Justice Institute, the legal arm of the Mississippi Center for Public Policy, sent a letter today to the Mississippi Department of Public Safety concerning the Department’s proposed boycott of Nike.

MJI outlined that a government boycott based upon a personal objection to speech made by a company is unconstitutional. This is the case whether it is the government boycott of Chick-Fil-A in Denver or Nike in Mississippi.

“A government boycott of a company for an exercise of free speech would be a flagrant violation of the First Amendment,” Aaron Rice, Director of the Mississippi Justice Institute, said. “For example, in Bd. of Cty. Comm'rs, Wabaunsee Cty., Kan. v. Umbehr, 518 U.S. 668 (1996), the U.S. Supreme Court held that the First Amendment protects independent contractors from the termination of at-will government contracts in retaliation for their exercise of the freedom of speech. In a similar case, the Court in Rutan v. Republican Party of Illinois, 497 U.S. 62 (1990) held that politically based refusals to hire are just as unconstitutional as politically based dismissals of employees. What is clear from these cases is that the government cannot use taxpayer money to punish speech, either by canceling existing financial arrangements or by refusing to enter into future business relationships.”

In the past, MCPP has clearly communicated its view that using the national anthem as a venue for protest at sporting events is not appropriate and the NFL has clearly suffered from the consumer backlash. However, there is a difference between consumers exercising rights based on personally-held views and the government attempting to do it on behalf of all citizens.

“As a proud American, and as a fellow military veteran who lost a leg in Iraq, I would not personally choose the national anthem as a venue for protest as Colin Kaepernick has, or to highlight this act as Nike has,” Rice added. “However, I fought to protect their right to do just that without fear of government retribution, and I am always heartened to see citizens actually exercising that right - even when I may disagree with their viewpoint.

“MCPP and MJI are private organizations with the objective, among other things, of holding government accountable to its proper role as defined by the Constitution. To look the other way simply because we may disagree with the speech in question would be to fail in fulfilling this objective.”

Read the letter here: https://mspolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Open-Letter-to-MDPS-Commissioner-9.27.18.pdf

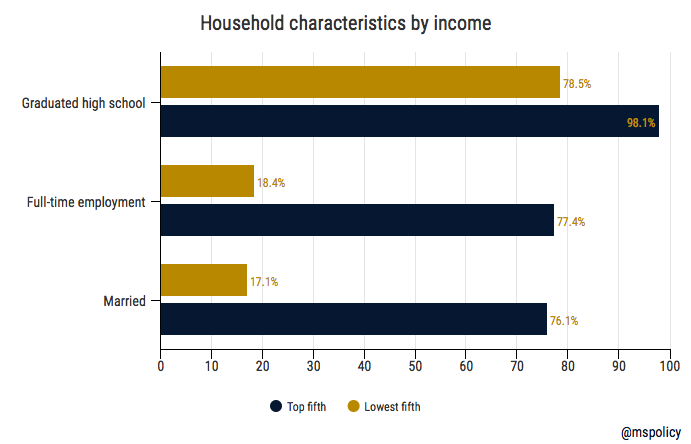

There is income inequality in America, but it is dictated by individual choices. Just three life choices can define if one will be trapped in a life of poverty or if they will be on a path to prosperity.

For years conservatives, and some liberals, have been advocating for what has been labeled the success sequence. On the surface it’s relatively simple, and there are some variations, but it generally looks like this: Graduate from high school, obtain employment, get married, and then have children only after you are married.

More people than ever are graduating from high school, though that may also be due to a decreasing of standards. Job prospects vary depending on the economy of the day, and where you live, but right now jobs are plentiful. But as we know, it is the second half of the equation – getting married and waiting until you are married to have children – that appears to be a little more difficult. And with dire results.

In the 1960s, as our country embarked on the Great Society and implemented social welfare programs in the name of combating poverty, out-of-wedlock births stood at less than 5 percent nationwide. That percentage had remained stagnant going back to the 1920s. But since the 1960s, it has spiked to over 40 percent.

In Mississippi, the latest numbers show 53.2 percent of children born in the state are to unwed mothers. Though that is slightly better than the 54 percent mark in 2014.

Why does this matter?

Well, here is what the data shows.

Of the lowest fifth earners in our country, those with an income range of up to $24,638:

- 21.5 percent did not receive a high school diploma.

- 18.4 percent of householders worked full-time. 68.5 percent did not work.

- 17.1 percent are married couple families compared to 82.9 percent who are either single-parent families or single.

Of the top fifth, those who earn more than $126,855:

- 1.9 percent did not receive a high school diploma.

- 77.4 percent of householders worked full-time.

- 76.1 percent are married couples compared to 23.9 percent who are either single-parent families or single.

Many things in life can dictate one’s income. Fortunately, when it comes to graduating high school, working, and getting married before children, each individual can control what path he or she takes.