Between a pandemic, murder hornets, and so much more, it is perhaps little surprise that studies have consistently found that Americans are drinking more alcohol during quarantine. In states around the country liquor stores and small businesses that deliver alcohol have seen an uptick in sales.

Mississippi, thanks to the infinite wisdom of our legislative class, has decided that we do not want to see the same economic gains and tax revenue brought forth from an increase in demand like in other parts of the country. An antiquated operations model that places a distribution monopoly within the hands of a single government entity and a series of laws that bar delivery and shipment of alcohol have handicapped the liquor industry in the state and desperately need to be reconsidered.

Liquor store owners in and around Jackson are saying that their deliveries are two weeks behind schedule.

Customers have long complained about the inability to get common alcohol selections due to the cutting of products from the Alcoholic Beverage Control (ABC) warehouse.

Responding to the present issues, Sen. Josh Harkins (R-Flowood) recently stated, “[W]e’ve got some incredible employees out there right now they’re limited in what they have the ability to properly distribute the product so we’re just trying to make it more efficient.”

While having employees is nice, a government program should not exist solely to offer jobs. Just because government can make money performing an operation does not mean that operation becomes a legitimate scope of government.

A few months ago, ABC officials said that orders had risen 29 percent and that they were considering suspending new orders. They ultimately announced a suspension of all orders from July 10 through July 20 before giving in to allow for more placements. Such drastic measures showcase the current inability of ABC to respond to changing market demand. While some suggest that the department simply needs more taxpayer resources, and a larger warehouse, a more dramatic solution is necessary.

ABC is perfectly making the case against its own existence and for privatization of their work. Government consistently proves itself to be an inefficient allocator of resources, and its departments are woefully unable to respond to rapid changes in the market context in order to adapt. Private distributors have greater flexibility to expand and contract depending on the performance of the market and thus should be empowered to do so.

One need only look to the most extreme example of late to see how the market ultimately reacts to changes in demand. When toilet paper sales spiked and aisles ran empty, stores kicked up their orders, and private distributors delivered, and yet months on, our government is still failing to respond effectively to a demand uptick that pales in comparison to the one for toilet paper over this year.

What purpose does Mississippi government have in the alcohol distribution business anyway? Government should no sooner step in to start distributing fried chicken and biscuits. Either way, it is a ridiculous misutilization of our tax dollars.

However, our legislators not only continue to invest in an antiquated system that is unable to fulfill the requests of both businesses and consumers, they also go so far as to block private entrepreneurs from delivering alcohol.

In states around the country apps such as Postmates, Drizzly, and others have helped make shopping easier by reducing the number of people in physical store locations at any given time. They have done so through vast delivery networks which allow one to get alcohol products delivered to one’s door just as food, groceries, and other commodities are readily delivered.

Unfortunately, due to a lack of foresight on behalf of our government, our legislators chose to continue restricting this freedom, eliminating potential new jobs, and necessitating people go into physical liquor stores during a pandemic.

Altogether, Mississippi alcohol policy continues to be defined by our unique history with prohibition. As the first state to enact it and the last to officially end it, the ramifications of this remnant of a bygone era continue to make themselves known. The new strains placed on ABC by changes in market demand call for a reevaluation of government control over alcohol distribution.

And, while we’re at it, let’s go ahead and let people use 21st century technology to order alcohol too.

Mississippians will cast their votes for president, a United States Senate race, each Congressional seat, medical marijuana, a new state flag, and more on November 3.

Here’s a breakdown to make it easier to vote.

Who can vote in Mississippi?

Every U.S. citizen who possesses the following qualifications is eligible to register to vote in Mississippi:

- A resident of Mississippi and the county, city, or town for 30 days prior to the election;

- At least 18 years old (or will be 18 by the date of the next General Election);

- Not declared mentally incompetent by a court; and

- Not convicted of a disenfranchising crime as defined by Section 241 of the Mississippi Constitution or by Attorney General Opinion, unless pardoned, rights of citizenship restored by the Governor or suffrage rights restored by the Legislature.

How do I register to vote?

You can register to vote in person or by mail in Mississippi. Regardless of the option you select, you must register by Monday, October 5. If you are registering by mail, it must be postmarked by that date.

To register by mail, you must complete a mail-in voter registration application. Provide the information requested, including your driver’s license number and/or the last four digits of your Social Security number. Then, send your Mail-In Voter Registration Application to the Circuit Clerk’s Office located in the county of your residence.

Want a mail-in voter registration form? Click here.

You can register in person at the Circuit Clerk’s Office, Municipal Clerk’s Office, Department of Public Safety, or any state or federal agency offering government services, such as the Department of Human Services.

What forms of photo ID are required to vote?

All voters must show photo identification when voting in person. Any of the following photo IDs may be used:

- A driver’s license

- A photo ID issued by a branch, department or entity of the State of Mississippi

- A United States passport

- A government employee ID card

- A firearms license

- A student photo ID issued by an accredited Mississippi university, college or community/junior college

- A United States military ID

- A tribal photo ID

- Any other photo ID issued by any branch, department, agency or entity of the United States government or any State government

- A Mississippi Voter Identification Card

Expired identification cards are acceptable as long as they have not been expired for more than 10 years.

How do I find my precinct?

Every address is located within a specific precinct and polling place. Not sure how to find your precinct? Click here to enter your address and find your polling place.

How do I vote absentee?

Some registered voters are eligible to vote by an absentee ballot because of age, health, work demands, temporary relocation for educational purposes, or their affiliation with the U.S. Armed Forces. Please check with your Circuit or Municipal Clerk to determine if you are entitled to vote by an absentee ballot and to learn the procedures for doing so.

And this year the legislature added COVID-19 patients under physician-imposed quarantine, or anyone caring for a dependent who is such a patient, as eligible to vote absentee.

If you know you will vote by an absentee ballot, you may contact your Circuit or Municipal Clerk’s Office at any time within 45 days of the election.

“Our farm is Heaven’s Blessings Family Farm.

“We raise sheep, goats, and our food. We have started raising mini Jersey and Dexters over the last six years. We bought standard Jersey again this year and also added Lowline Aberdeen. We also have chickens and Hereford hogs and Duroc. We sell calves from our cows once they are weaned, halter trained, and will lead. We have sold eggs and hatched eggs to sell chicks, but we no longer do at this time.

“We have had several people ask us to purchase raw milk, but we aren’t allowed to do that in Mississippi.

“We put a lot of money into our animals for feed, hay, vets, minerals, vitamins, plus meds when needed. If we could sell our milk, butter and other things we grow or make it could help with these costs.

“Our farm would actually support itself and we wouldn’t have to take our earned money off our jobs if our farm could supplement our income.”

Johnny and Carrie Beal

Heaven’s Blessings Family Farm

Richton, Mississippi

Mississippi lawmakers have been rebuilding the state’s rainy day fund since it was nearly depleted last decade. And today the state is doing better than many others when it comes to saving.

This is something that always been relevant, but became exceedingly important from the COVID-19 related recession.

The balance of the rainy day fund has been steadily growing to around $460 million today. This represents a healthy eight percent, which is comparable with the national average of general fund expenditures. In 2013, it stood at just $32 million, about 0.7 percent of all expenses.

Mississippi’s rainy-day fund

| Year | Rainy-day balance | % of expenses |

| 2013 | $32,000,000 | .7% |

| 2014 | $110,000,000 | 2% |

| 2015 | $395,000,000 | 7.1% |

| 2016 | $350,000,000 | 6.1% |

| 2017 | $269,000,000 | 4.7% |

| 2018 | $295,000,000 | 5.3% |

| 2019 | $350,000,000 | 6.3% |

| 2020 | $465,000,000 | 8.1% |

| 2021 | $464,000,000 | 7.9% |

As for neighboring states, Mississippi is doing better than most. Alabama is the only state where the rainy day fund makes up a larger chunk of their budget, at 10.9 percent. Tennessee, Louisiana, and Arkansas have rainy day funds of 6.8 percent, 5.8 percent, and 2.7 percent, respectively.

Rainy day fund, neighboring states

| State | % of expenses |

| Alabama | 10.9% |

| Arkansas | 2.7% |

| Louisiana | 5.8% |

| Mississippi | 7.9% |

| Tennessee | 6.8% |

“Rainy day funds are a reflection of deliberate state policy choices by elected officials. In recent years, governors and state lawmakers have focused on rebuilding their states’ rainy day funds. Rainy day fund balances, in the aggregate, have grown substantially since the Great Recession, reaching $75.5 billion in fiscal 2019 (with a median balance of 7.3 percent as a share of general fund spending). Before the COVID crisis, states were expecting to end fiscal 2020 with a median rainy day fund balance of 7.8 percent, a new all-time high. By comparison, going into the last recession, the median rainy day fund balance in fiscal 2007 was 4.6 percent,” the report notes.

Mississippi’s rainy day fund, while smart fiscal policy, has been a bit of a political football with some lawmakers criticizing the state for saving while they push for more government spending during better economic days. But this prudence paid off when the coronavirus pandemic and the associated economic collapse hit earlier this year. Yes, the federal government has dumped boats of cash in Mississippi and every other state, but that can’t and shouldn’t be what any state turns to during bad times.

Especially in Mississippi, a state that relies on the federal government more than most states.

We’ve learned from the Great Recession to be prepared. And that is what will help the state be prepared fiscally for the future. It is about making smart fiscal decisions, particularly during good times, resisting the temptation to spend every dollar you have, and living within your means. It’s something households do every day.

It’s something all states could and should do.

When legislators return in January, they will have a full slate of issues to tackle.

What would you like to see members work on? Select the issues below you would like to see the legislature work on, or add your own.

“I started this business when I was 16 years old. We specialize in self-defense. But I did not realize when I opened that I would need self-defense not only from a virus, but also from our government.

“I got started with martial arts when I was five years old. I had the opportunity when we moved back to Mississippi to get introduced to Gracie Jiu-Jitsu. Through training for several years, I learned about the instructor certification process and program. I was given the opportunity to get certified when I was 16 years old and opened the school here that same year.

“I was homeschooled from fifth grade on and I was never really held back by age. My parents were super supportive in my endeavors as far as opening the school. No doubt it was absolutely terrifying and super scary initially because you’d have a 16-year-old teaching people two or three times his age. And having to make big decisions that affect the business.

“Ultimately, it’s been my passion, my love, and I wouldn’t trade it for the world.

“When we first started, we started with absolutely nothing, we had zero students, zero anything. We had a beautiful school, beautiful facility, with nobody. Shortly after that we started building up our clientele base through word of mouth, social networking, things like that. Built a solid clientele base, got to over 200 students, and then March 4 everything kind of went sideways.

“The roof from the building across the street from us flew into our building with the storm. We got hit with that, completely wrecked the school, broke out front doors, destroyed our women’s locker room, destroyed our mats. The following week all of the COVID restrictions came down the pipeline. To say that hurt would be a very big understatement.

“Our clientele base started slowly dropping off and then we dropped off like crazy. We lost over 50 percent of our students, that’s kids and adults. One, because of fear of getting out, and the government restrictions, not wanting to do a class where they can’t get the full impact and full potential of the program.

“With that being said, insurance is still wanting their money. Our bills haven’t gone down by 50 percent just because we lost 50 percent of our clientele base. We’re still plugging away. We’re still trying to make everything happen. We have employees who we’re trying to keep food on the table and unfortunately the regular costs have not gone down just the clientele base all because of COVD.

"Small businesses are absolutely essential. A community cannot survive without the small business in it."

Houston Cottrell

Gracie Jiu-Jitsu

Madison, Mississippi

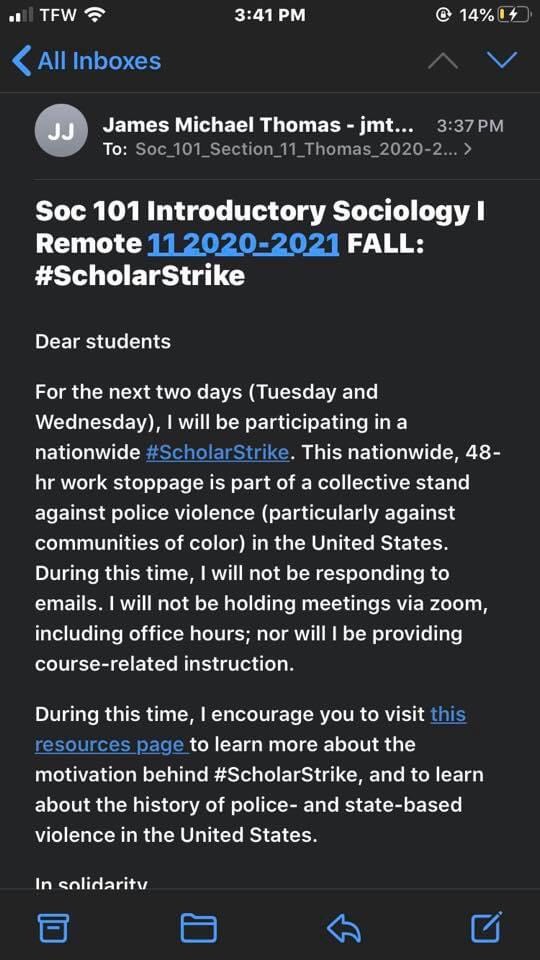

Ladies and gentlemen, Ole Miss professor James Thomas has left the building. Don’t get too excited, he’s just taking a five-day weekend.

In an email correspondence late Monday afternoon the self-described “Insurgent Prof” informed his pupils he will not be holding any meetings, office hours, or instruction through Zoom or otherwise the Tuesday and Wednesday of this week; leaving students hanging as they enter what is traditionally the kick off for major graded assignments.

Thomas isn’t the only academic taking it easy this week. This corresponds with what has become known as the #ScholarStrike, a movement started by self-described intellectuals to protest police brutality toward communities of color by skipping work.

One must wonder if students would be afforded the same privilege when it comes to project deadlines or absences.

Perhaps not.

Concluding the email, the newly tenured professor of sociology referred his pupils to a “facts sheet” provided by the striking organization that covered instances of police brutality alongside the organization’s political beliefs; signing off with “In Solidarity.”

This shouldn’t come as a surprise as solidarity with his fellow radical liberal academics has become a bit of a calling card by the most notorious professor at Ole Miss.

While students are forced to pay full price this semester for a hodgepodge of sub-par virtual instruction via Zoom, Thomas and his close allies in department administration are all too comfortable exploiting students complacency by taking long weekends, sending out political speech in official emails, and falling short in their obligations as educators; just so long as it fits the woke agenda of 2020.

Ole Miss has been struggling with the “Get Woke, Go Broke” reality of higher education for years, and while there have been many recent improvements to the cohesiveness of our state and its flagship institution, bias from liberal academics still remain a serious threat to the next generation of Mississippians.

Ole Miss shouldn’t have to cave into the politically correct mob or to indifferent academics that choose to be outraged enough to skip work when they already get a long weekend. It’s time Ole Miss rediscover it’s values as a scholarly hub where the free market of ideas flourish, where student-professor relationships based on mutual respect not uniformity of thought are primary.

If we are to restore these values Ole Miss would be a beacon to all across the nation of governance in higher education.

Mississippi’s State Fair will continue as scheduled next month. It will just look a little different.

To date, at least 35 fairs, including the famous Texas State Fair, have been cancelled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. But not Mississippi.

Andy Gipson, Commissioner of Agriculture and Commerce, recently announced the 161st State Fair will run from October 7 through October 18 as planned.

“If you need to stay home, I encourage you to stay home,” Gipson said. “But for those who are getting out and want to get out and make family memories, I invite you to come October 7-18.”

Here are some of the new safety protocols this year:

- All staff (Midway employees, MDAC employees, contractors, and vendors) will be required to wear masks. All participants will be required to wear face coverings upon entry. If someone shows up without a face covering, the Fairgrounds will provide a mask. Adult and children’s sizes will be available.

- All gates into the Fairgrounds will be equipped with one or more people with digital devices to account for visitors as they come and go to ensure the 200-people-per acre capacity is not violated. Entrance will be denied if capacity is met.

- The Midway will be expanded and lines will have six-foot markers to demonstrate social distancing.

- Multitudes of hand sanitation stations will be provided throughout the Fairgrounds.

- High touch areas and surfaces will be routinely sanitized.

- The Senior American Day program and the School Field Day will not be held this year.

“By using common sense and looking out for each other, we will have a great Mississippi State Fair, we will continue to make family memories while being safe and healthy,” Gipson added.

“I run Bailey Farms and would like to see food freedom expanded in Mississippi.

“We have a small farm. Ten or so beef cows, three jersey dairy cows, a few pigs, and a yard full of chickens.

“We just recently sold out our commercial rabbitry. We had around 100 breeding doe rabbits. So with all the kits and fryers we usually had around 500 rabbits at one time. Now we are slowly growing a small calf cow operation with the intent of selling some grass-fed beef in the future. I am currently clearing more land for pasture.

“If I were milking 10 cows, I could sell every drop of raw milk. There are studies that show the benefits of raw milk. I encourage everyone to do their research.

“I know people question raw milk but do your own research and make an informed decision. If you think it’s dangerous, don’t buy it. We use belly style milkers that are cleaned and sanitized after every use. I literally see every ounce of milk we pour into glass jars.

“I would encourage people considering raw milk to visit their local dairy farm and decide for themselves. We have healthy happy cows that live in pastures and eat grass. Mississippi State’s dairy cows spend 3/4 of the year living on concrete.

“If you buy a bad gallon of milk at the store, you pour it out and go back to the same store and buy another.

“If I sell bad milk (which is hypothetical of course because selling raw milk is illegal), people won’t come back. So, I have an increased sense of awareness to making sure everything is clean and sanitized.”

Heath Bailey

Bailey Farms

Eupora, Mississippi