New York made headlines recently for passing legislation that will legalize abortion to the moment of birth.

The New York state Senate voted 38-24 in favor of the “Reproductive Health Act” last week. This bill has passed the state Senate before but has failed to pass the Assembly in past years. This time, the Assembly passed RHA 92-47.

Press and social media have been in outraged battles over the passage of this state legislation. The implications of this law have shaken up the entire nation.

In Mississippi, it has triggered an influx of volunteer applications and donations to pregnancy help centers from appalled Mississippians across the state.

The cleverly named “Reproductive Health Care Act” is horrific and unconscionable.

This law has five major consequences that should incite fear and disgust in us all:

- It legalizes abortion past 24 weeks until the moment of birth;

- It decriminalizes the death of any preborn child, meaning the murder of a pregnant woman cannot be ruled a double homicide;

- RHA legally makes abortion a “fundamental right” according to state law;

- It oddly allows licensed health practitioners who are not abortion doctors to commit abortions; and

- By declaring abortion a “right,” it follows the extreme left’s trend of implementing state laws that will uphold the abortion industry in the event that the Supreme Court overturns Roe vs. Wade.

Most level-headed Americans are appalled at these changes to the New York penal code. Sadly, abortion has only been limited in the third trimester in 43 of our 50 states prior to this legislative session.

What took America over the edge was New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo calling for the entire state to celebrate following his signing of the bill into law. He called for One World Trade Center and other landmarks to be lit in pink, exalting the decision.

Cuomo, who is Catholic, maintains his support of the law despite pending talks of his excommunication from the Catholic Church for violating fundamental beliefs of his own faith. In defense of his unjustifiable actions, he stated, “I’m not here to represent a religion.”

Any decent human can understand the humanity of a child in the third trimester no matter race, religion, or creed.

In an attempt to one-up Cuomo, Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam advocated that post-birth abortions ought to be allowed in his state. He voiced support of a bill in his state allowing abortion up to the moment of birth even if the baby was born alive by accident.

A baby born alive would be “kept comfortable” and only “resuscitated if that’s what the mother and the family desired.” If a mother did not want the child born alive, that baby would be left to die a slow and painful death at a medical facility with medical professionals present.

Fortunately, that bill was defeated in committee.

In our state, Mississippi Center for Public Policy advocated a bill last year that banned abortion after 15 weeks gestation. It was halted 30 minutes after Gov. Phil Bryant signed it into legislation by a temporary block. In November, activist District Judge Carlton Reeves blocked the law. Mississippi has not given up Bryant’s dream of making Mississippi the “safest place for an unborn child in America.” The 5th U.S Circuit Court of Appeals will be next to hear the case.

As the law stands, abortion is legal up to 20 weeks gestation in Mississippi.

Mississippi is listed as one of four “trigger law states” that will almost immediately ban abortion if the 1973 decision of Roe vs. Wade is reversed. The abortion lobby is working creatively to prevent states from limiting or banning abortion at any level.

Mississippi may be in far better shape than states like New York or Virginia, but we must remain vigilant in defending our state’s right to rule in defense of preborn children.

Someone has to stand for the life of the preborn while the left crowns the “right to choose” as more valuable than life itself.

There are many things we can do to lift up all children. And we don't need to sacrifice our own children to make that happen.

In a recent NBC Think article, author Noah Berlatsky reflected on Mississippi State University (MSU) Assistant Professor Margaret Hagerman’s new book “White Kids: Growing Up with Privilege in a Racially Divided America.” Berlatsky opens with the conflicting pride he felt when his child lobbied his private secondary school to recognize Columbus Day as Native People’s Day because the school should not celebrate “white imperialism.” (His son’s effort was successful.)

Ignore for a moment that Columbus Day is a celebration of human achievement, global trade, and multiculturalism that has been celebrated for more than a century, including in multiple Latin American, non-white countries. Ignore also that instead of educating the student on the rich tradition of this holiday, the school wasted time accommodating an uninformed child’s protest about a holiday he clearly doesn’t understand.

Held up to any scrutiny, this situation is absurd, but not more absurd than Berlatsky’s reflections on it. Berlatsky is conflicted because, while he is proud of his child’s “anti-racist activism,” he feels shame for his white privilege affording his child an education at an expensive private school where school administrators take such activism seriously. In his view, this exemplifies the much larger problem of structural racism. He then explores the MSU professor’s book.

How About Help the Needy Instead of Hurting Children?

One of the many lazy assertions in this book is that even anti-racist white parents “actively reproduce inequality” by not spending enough time discussing racism with their children and by giving their children books whose characters happen to be white. There is no end to the left’s shaming of people who have done nothing more than teach their kids to be good people to the best of their ability.

Berlatsky has done nothing wrong, and unlike Hagerman suggests, Noah has not actively reproduced racism. On the contrary, his son obviously demonstrated his awareness and opposition of racism at a young age. In an attempt to appease his ideological possession, Noah brainstorms over possible lifestyles choices that might mitigate his child’s privilege footprint.

He pulls from Hagerman’s book: “Everyone is trying to do the best for their kid,” she says. “But I actually think that there are times when maybe the best interest of your own kid isn’t actually the best choice. Ultimately, being a good citizen sometimes conflicts with being good parents. And sometimes maybe parents should decide to be good citizens over being good parents.”

Berlatsky mulls over a few examples of this. “That could mean voting to raise taxes so to better fund public schools. Maybe in our case it should have meant choosing a public school rather than a private one.”

This Isn’t Only Stupid, But Evil

It’s incoherent, at best, to imply that worse parents make better citizens. While white liberals ponder the various ways they should have neglected their kids to appease “oppressed groups,” I and many other millennials reject this ideological disease.

I am a young, half-white mother and wife who has seen the expansion of the radical left politically correct culture since I was in elementary school. When Gillette is lecturing you about how to behave, you know things have gone too far. The only result of this decades-long Marxist campaign is more outrage at good people.

According to many on the left, I am supposed to teach my son of the repressive nature of his existence as he develops. I am to tell him at every turn to sacrifice himself to others for the transgression of being himself. This thinking is not only intellectually pitiful, but also profoundly evil.

How About Some More Constructive Responses

The smallest minority is the individual. I reject the notion that my son’s value is determined by his skin color, sex, or life circumstance. I look forward to teaching my son about self-discovery. I want to see him develop his talents and learn to appreciate the talents of his peers. I want him to feel the joy of hard work and achievement, and to admire the qualities of others in a society that appreciates individuals.

If we raise our children to appreciate individualism, then we will end all the various flavors of collectivism, from racism to white privilege. Teaching our children about the horrors of imperialism, slavery, and racism is critical. However, there is no greater good to be gained by sacrificing the quality of my child’s education or economic circumstance.

To maximize the quality of each child’s path to quality education, economic prosperity, and social well-being, I propose a few different policy points. School choice, not mandated-by-ZIP code education, will give children the propensity to thrive. Rather than blame individuals who move to a highly rated school district or make them feel guilty for choosing to send their child to a private school, open the door to more students to do the same.

Eliminating barriers to economic progress, such as excessive licensing, will create a world of jobs for entrepreneurs, especially low-income entrepreneurs. While licensing was once limited to areas that most believe deserve licensing, such as medical professionals, lawyers, and teachers, this practice has greatly expanded over the past five decades.

In my home state of Mississippi, approximately 19 percent of workers need a license to earn a living. This includes everything from a shampooer, who must receive 1,500 clock hours of education, to a fire alarm installer, who must pay more than $1,000 in fees to become licensed. In total, there are 66 low- to middle-income occupations that are licensed in Mississippi. Similar stories exist is every state, yet the outcomes are the same: higher cost for consumers and less opportunity for entrepreneurs.

Finally, promoting, or at the very least not discouraging, marriage will lead to more intact families and the benefits that surround it. The success sequence––graduate from high school, obtain employment, and get married before having children––has long been debated, but it is undeniable from numerous points of view that following these (not so simple) steps will put an individual, and a family, on the path to prosperity.

This, of course, will require a cultural response, similar to anti-smoking campaigns, as much as a government response. Unfortunately, too few people seem interested in taking up the cause of marriage, despite it being the leading cause of inequality in American children’s lives.

I want what is best for my son, and I will do what it takes to make that happen, no matter the political trends. And that is the best thing we can do for a better society.

This column appeared in The Federalist on January 30, 2019.

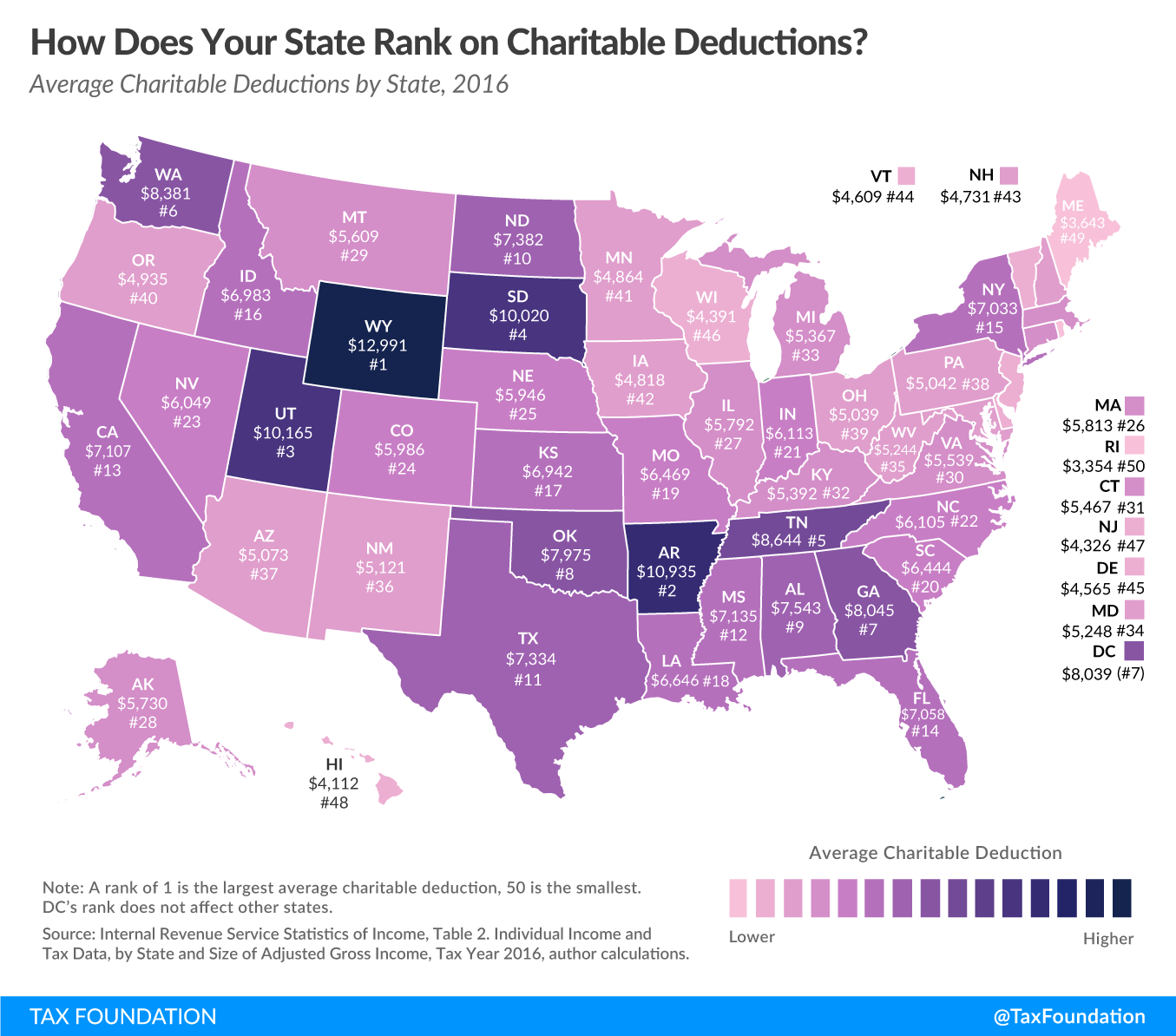

As many prepare for end-of-year charitable contributions, data from the Internal Revenue Service continues to show Mississippi as one of the most charitable states in the country.

According to the IRS, some 250,000 Mississippians took an itemized deduction for charitable giving last year. The average deduction in the Magnolia State was $7,135. This is the 12th highest average in the country.

The top five charitable states were Wyoming ($12,991), Arkansas ($10,935), Utah ($10,165), South Dakota ($10,020), and Tennessee ($8,644).

Along with two of Mississippi’s neighbors coming in the top five nationally, Alabama placed ninth at $7,543 per contribution and Louisiana was 18th at $6,646 per contribution.

The five least charitable states were Rhode Island ($3,354), Maine ($3,643), Hawaii ($4,112), New Jersey ($4,326), and Wisconsin ($4,391).

As a note, this isn’t necessarily total amount of giving, but the total amount that eligible taxpayers deducted on their income taxes in 2016. A donation that was made but not reported on tax filings would not be counted in this report.

And as the standard deduction will be increased because of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act that passed last year, it is assumed that far fewer individuals and families will itemize their deductions this year. That will impact tax filings, but what effect it has on actual charitable giving remains to be seen.

Today, abortions are occurring less often in America than they have at any time since the Supreme Court legalized abortion in all 50 states in 1973.

Laws on legal abortion vary from state to state, with Mississippi setting the limit to abortion at 20 weeks gestation. The state’s ban on abortions after 15 weeks has come to a pause as it fights its battle in the courts.

Despite the temporary setback, recent Center for Disease Control reports on abortion rates have brought good news to those on the pro-life side of this issue.

The CDC’s 2015 report indicates a downward trend in abortions since their climax in the 1980s. In 2015, the United States experienced 638,169 abortions. This is a two percent drop from 2014 data. In Mississippi, abortion percentages reflect this trend.

Hinds County, home to the only abortion clinic in the state, ranked first in abortion rates. But, it saw a drop from 23.2 percent to 20.7 percent of pregnancies ending in abortion. Still, one in seven pregnancies ending in abortion in Hinds, Rankin, and Madison counties is nothing to celebrate.

However, it is worth investigating what is causing this downward trend—especially if we want it to continue. One correlation is the rising number of pregnancy centers.

Charlotte Lozier Institute’s 2018 Pregnancy Center Report showed that an estimated two million people received free services at pregnancy centers this year. These pregnancy centers operate as private nonprofits and ministries with an estimated 67,400 volunteers including 7,500 licensed medical professionals. And they have saved American taxpayers an estimated $161 million.

Nationally, the National Institute of Family and Life Advocates had a huge 2018 Supreme Court victory that saved the longevity of these centers from state legislatures who would rather see them shut down. In Mississippi, we can claim over 40 pregnancy centers and clinics. The largest pregnancy medical clinic in the state is The Center for Pregnancy Choices-Metro Area, with two locations in Jackson. These pregnancy centers offer pregnancy tests, sonograms, supplies, referrals for adoption and medical needs, counseling, and parenting classes as some of their services.

The pro-abortion lobby frequently targets pregnancy centers that save taxpayers millions and offer compassionate, free services to women facing unplanned pregnancies. “Fake Clinic” is the branded name given to pregnancy centers by the pro-abortion community. In our state’s capitol, “Fake Clinic” signs and fliers have littered our streets with the hope of swaying women against attending their appointments with The CPC. Instead, patient numbers have increased at metro area clinics. And ninety-four percent of patients leave reporting full satisfaction from their visit. Not one patient has reported a poor experience on exiting surveys.

One wonders if a government agency ever received such phenomenal reviews.

The numbers speak volumes. The free market is handling the subject of unplanned pregnancies far better than any government agency. The private donors, volunteers, and pregnancy center employees of Mississippi are driving solutions to end abortion in our state.

Anja Baker is a Contributing Fellow for Mississippi Center for Public Policy.

We can learn many wonderful lessons from Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. But more than that, it is something families with young children have enjoyed for generations.

On the Day after Thanksgiving, my wife, my three boys, and I sat down to watch the classic holiday movie, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. Since that time, the boys have asked me to read the original book each night before bedtime. And I’m pretty sure they’ve asked their mamma to read it a time or two during the day.

Unbeknownst to me, I was apparently subjecting my children to levels of sexism, racism, homophobia, and bullying that may never be repaired. And you can go ahead and add any other phobias or “isms” that diligent, gender studies majors busy themselves discovering and warning the rest of us about.

Yes, Rudolph is the latest subject of our outrage culture. It seems there are more and more people who live their lives to be outraged. But this outrage seems quite the stretch.

As you probably know by now, this is not a joke, but an actual argument from Huffington Post. While most of America is laughing at the outrage, there are some who literally wake up each morning, scour the latest news, and then find something about which to be offended by. And then they write about it. And outlets like Huffington Post publish it

What is the goal? To bring down what you and I love? To shame the traditions people grew up with or the pastimes that make us feel good? If someone wants to be outraged by something, anything, they can be. They simply pick something, add an “ism” to it, and the story is written. However, in this case the story is really an attack on something families have enjoyed together for generations – a classic holiday tale. Personally, I don’t think it’s by accident.

These attacks are not isolated to Rudolph, and this won’t be the last time. When this passes, there will be something else in our culture to petition.

In this case, as is becoming the norm with the social outrage crowd, the attack doesn’t even make sense. Spoiler alert, the previously outcast misfit toys end the reign of terror brought on by the Abominable Snow Monster. Rudolph, the formerly shunned kid with unique qualities, saves Christmas and becomes the hero. The minority characters who were previously neglected and unfairly treated, are welcomed into the community and the lonely misfit toys are given loving homes.

Social justice is delivered by the acts of individuals seeking their place in the world and discovering the usefulness of their own individual blessings and others coming to recognize those gifts. No, there were no transgendered reindeer. Mrs. Donner doesn’t attend feminists book studies with Mrs. Claus. And the elves didn’t create a union and force members to pay mandatory dues. But the classic movie does teach a wonderfully “woke” story about the value of life and how we all have purpose in this world, even if it takes us, or our neighbors, a while to understand it.

Some people will never be happy. But whether it is something serious or a movie about a reindeer with a red nose, we should never give in to this authoritarian mob seeking to find offense with every tradition some may hold dear. With this mob, no concession will ever be enough.

I’m reminded of another classic children’s story in which the author warns, “if you give a mouse a cookie, he’ll just ask for a glass of milk.”

There is income inequality in America, but it is dictated by individual choices. Just three life choices can define if one will be trapped in a life of poverty or if they will be on a path to prosperity.

For years conservatives, and some liberals, have been advocating for what has been labeled the success sequence. On the surface it’s relatively simple, and there are some variations, but it generally looks like this: Graduate from high school, obtain employment, get married, and then have children only after you are married.

More people than ever are graduating from high school, though that may also be due to a decreasing of standards. Job prospects vary depending on the economy of the day, and where you live, but right now jobs are plentiful. But as we know, it is the second half of the equation – getting married and waiting until you are married to have children – that appears to be a little more difficult. And with dire results.

In the 1960s, as our country embarked on the Great Society and implemented social welfare programs in the name of combating poverty, out-of-wedlock births stood at less than 5 percent nationwide. That percentage had remained stagnant going back to the 1920s. But since the 1960s, it has spiked to over 40 percent.

In Mississippi, the latest numbers show 53.2 percent of children born in the state are to unwed mothers. Though that is slightly better than the 54 percent mark in 2014.

Why does this matter?

Well, here is what the data shows.

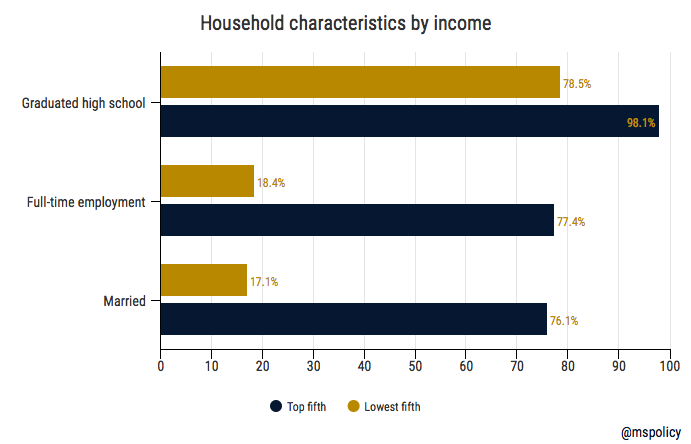

Of the lowest fifth earners in our country, those with an income range of up to $24,638:

- 21.5 percent did not receive a high school diploma.

- 18.4 percent of householders worked full-time. 68.5 percent did not work.

- 17.1 percent are married couple families compared to 82.9 percent who are either single-parent families or single.

Of the top fifth, those who earn more than $126,855:

- 1.9 percent did not receive a high school diploma.

- 77.4 percent of householders worked full-time.

- 76.1 percent are married couples compared to 23.9 percent who are either single-parent families or single.

Many things in life can dictate one’s income. Fortunately, when it comes to graduating high school, working, and getting married before children, each individual can control what path he or she takes.

Graduating from high school, obtaining employment, and getting married before having children is still the best path out of poverty.

A recent essay in the New York Times tells the story of a life in poverty. This same story could be told of countless individuals in Mississippi.

Unfortunately, something that could be productive for a larger discussion misses that mark. Under the headline, “Americans want to believe jobs are the solution to poverty. They’re not,” we learn about the struggles of Vanessa Solivan, a home health aide in New Jersey.

Vanessa is a single-mom with three children. As a home health aide, she makes between $10 and $14 per hour. She works part-time, between 20 and 30 hours a week. If we took the average of both those numbers, 25 hours a week at $12 an hour, Vanessa would make a little more than $15,000 a year. Even with the Earned Income Tax Credit, before other welfare programs, she would only be bringing in about $20,000 per year.

No one would argue that is not enough to live on, particularly with three kids. Though, Vanessa’s story isn’t quite aligned with the headline.

Full-time jobs, and a two-parent household, are the solution to poverty; not single-parents with part-time jobs

Why is Vanessa only working part-time? She wants to work more hours but can’t. Several years ago, during the Obamacare debate, Republicans rightly were arguing that these new requirements will only encourage employers to prefer part-time workers. We often talk about the law of unintended consequences when it comes to government policy, but this was a consequence you didn’t need a public policy degree in order to predict. But policy makers just chose to ignore it. Or they blamed business owners for the terrible sin of “worrying about their bottom line.”

If Vanessa were working full-time, her income would be closer to $30,000, roughly a third more income to make her household budget a little more manageable.

While there is certainly nobility in working in healthcare, if Vanessa had a better K-12 education than most who grow up in poverty, could she have been better prepared for a more sustainable career path? Perhaps if she had had access to a voucher, tax credit scholarship, or a charter school, her career would have gone in a different direction and she would have a higher income today. But alas, to most on the left, the path to better public education outcomes will only come from spending more money, despite decades of evidence to the contrary

And what about the fathers of Vanessa’s three children? One is dead from a gunshot wound after spending time in prison. The others provide occasional support, but nothing of substance. Unfortunately, this is a story that is very common in America today. Since the 1960s, when our country adopted most welfare programs in the name of a “Great Society,” out-of-wedlock birth rates have gone from about 5 percent to over 40 percent. In Mississippi, it’s 53 percent.

And disastrous results have followed

According to newly released Census data, only 17 percent of the lowest fifth income earners, those who make less than $25,000, are married. Conversely, 76 percent of the highest fifth, those with an income above $125,000, are married.

Now, if Vanessa had followed what conservatives refer to as the “success sequence,” and obtained employment and got married before having children, the New York Times writer would have had quite a different story. Even if we assume she is working the same job, and her husband enjoyed a comparable salary, the couple would be making about $48,000 per year working full-time.

The underlying message in a story like this from the New York Times is that the economy does not work for everyone. Jobs aren’t the answer. No one is dismissing the plight of those who struggle. But simply providing more welfare benefits will not move Vanessa, or others like her, off this generational cycle of poverty.

Rather, it starts with smart policy, like the Hope Act that Mississippi adopted in 2017, modeled after 1990s era “welfare-to-work” reforms. The new law requires able-bodied individuals without dependents to obtain employment or job training to continue receiving food stamps. And the path up the economic ladder includes the work of churches, non-profits, and the private sector reaching out and providing a helping hand in ways that only they can.

Those who start out in poverty certainly start out further behind. But we know there are paths to a better future. The problem is that the government, unfortunately, is usually more of a barricade than a guiding light on that path to more prosperity and opportunity.

This column appeared in the Madison County Journal on September 20, 2018.

The Family First Initiative Summit, hosted by Governor Phil Bryant, First Lady Deborah Bryant and Mississippi Supreme Court Justice Dawn Beam, was recently held to bring together leaders across the state to work together to address the problems created by multigenerational family breakdown. In welcoming attendees, Gov. Bryant affirmed that Mississippi is already being recognized as a leader among states in reunifying families and helping children in crisis.

Part of the solution is an innovative public-private partnership between the Mississippi Department of Human Services and Families First for Mississippi, a Mississippi-based nonprofit. The aim of the partnership is to provide wraparound services – whether it be job training or family counseling – that helps families get back on their feet. The goal of the summit was to create a network to expand these services and help Mississippi families. As Dr. John Damon, CEO of the Mississippi-based nonprofit Canopy Children’s Solutions put it, “If families get just a little bit of help, they can make it.”

Longtime supporters will know that MCPP has played a significant policy role in helping strengthen Mississippi families, overseeing passage of a gold-standard welfare-to-work reform and, this past session, helping pass a tax credit for donations to nonprofits who work with children in crisis, children with special needs, and low-income families. We are proud to continue to partner with the Governor and the First Lady in creating a Better Mississippi.

Pregnancy centers in Mississippi are providing free support and services for women that will eliminate the demand for abortion, regardless of any new rulings from the Supreme Court.

It is a wonderful time to be a pro-life Mississippian. It’s an even greater time to be a pro-life Mississippian with passion for free markets. The Center for Pregnancy Choices- Metro Area, with two Jackson locations, is a force to be reckoned with for our state’s abortion industry.

In fact, the Fondren and Frontage Road centers may just be the thing that makes Mississippi the first abortion-free state in the nation.

Supreme Court’s latest decision on pregnancy centers brought us closer to that reality than ever

If it were not for the Supreme Court rulings of Roe vs. Wade and Doe vs. Bolton, Mississippi would likely already be free from the requirement of legal abortion. Time and time again, abortion laws have passed our state legislature, often with the tireless work of the Mississippi Center for Public Policy, only to be halted by activist judges, and ruled as “undue burden” in the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals. The “undue burden” that halts the courts from ruling in favor of our state’s wishes refers to women needing to leave the state to find doctors who will commit abortions. It takes time to overturn court decisions, pass legislation, and see court seat changes.

The Center for Pregnancy Choices- Metro Area isn’t willing to wait for court processes to end abortion in our state. Private donors, churches, and local community groups fund free services that wipe out the demand for abortion far before the courts catch up to the conscious of Mississippi residents. With one lone abortion facility in our state, Jackson Women’s Health is standing on one leg.

The death of over 2,500 Mississippi babies annually takes place in the famous “pink house” in Fondren. Nearly half of the women obtaining abortions are from Hinds, Madison, and Rankin Counties. To put that in perspective, 1 in 7 pregnancies end in abortion in the tri-county area. Despite being a pro-life state, despite our overwhelmingly pro-life legislature, and despite our Bible belt reputation, abortion remains a reality for thousands of women in our state.

This is where The Center for Pregnancy Choices- Metro Area penetrates the market—with compassion and practical care

The CPC Metro Area offers medical-quality pregnancy tests, high-quality sonograms, counseling, literature, parenting classes, referrals to community services, infant supplies, and prenatal vitamins for free. Conversely, the JWHO abortion facility charges hundreds of dollars for consultations, sonograms, and counseling all pointed towards their highest profit product: abortion. They do not offer support for women desiring to carry their pregnancies to term. Under the banner of “choice,” women often enter and leave JWHO feeling as though abortion is their only choice.

The nurses and staff of The Center for Pregnancy Choices- Metro Area journey alongside pregnant women of all ages, races, and backgrounds to ensure they are informed of all resources available to them. A woman who enters the CPC Metro Area is counseled by a trained professional to hear her story and educate according to her needs. She will then receive a free sonogram, where she will be able to see her baby. She will leave with prenatal vitamins and literature to help make her decision. This woman can return or call back for help at any time she needs to be heard. Following her decision to carry to term, she can enroll in free parenting classes to prepare for her unplanned parenting experience and receive supplies such as diapers and clothes as incentive for participating. Following her decision to abort, she may still return for post abortive healing sessions with a group Bible study.

When a woman learns that there are ways to meet the needs of her unplanned pregnancy, she often feels the relief of not having to go to the pink house across the street. Instead, the entire staff celebrates her, her pregnancy, and her child.

Heavy, burdensome regulations threatened the freedom of pregnancy centers like The CPC Metro Area around the nation

The narrow 5-4 NIFLA vs. Becerra decision to protect the rights of charitable pregnancy centers is monumental. The law in question placed burdens on pregnancy centers that would force their staffs to betray their own conscience and offer confusing, conflicting information. Pregnancy resource clinics would have been mandated to include information on how to obtain abortions and, if not medically licensed, required to display a lengthy disclaimer in several languages that they do not employ medical professionals.

These charitable organizations, that save states millions of dollars with their non-governmental services, were to be treated as “fake clinics” with ulterior motives. Imagine visiting a salad bar and noticing mandated advertising of the burger joint next door. This is the world the “pro-choice” community wanted for pregnancy options. Instead, the court ruled that it was indeed the right of the pregnancy centers to offer their free services without the burden of intrusive advertisement regulation.

With Justice Kennedy’s seat pending for confirmation, many Americans are hopeful that the courts will catch up to the desires of states to determine their own conscious on abortion legality. In the meantime, the Center for Pregnancy Choices- Metro Area will be here, in Jackson, meeting the real needs of Mississippi women.

English statesman William Wilberforce and his Clapham Sect that started the movement to end the slave trade believed that culture is upstream from politics. Mississippi, the Hospitality State, the most philanthropic state in the nation, and arguably the most pro-life state in the nation, is that culture shift. We will rise up and meet the needs of women beyond the date that politics catches wind of our success.