The education setting for many children in Mississippi shifted this year. Perhaps the numbers weren’t as dramatic as mid-summer polling indicated, but the number of homeschoolers has increased by 35 percent over the previous year.

According to unofficial data collected by the Mississippi Department of Education, 25,376 students are homeschooling this year. These numbers aren’t final and may increase. Families are required to submit a certificate of enrollment form for each child who is homeschooled by September 15. Generally, families don’t submit forms for kindergarteners because compulsory education in Mississippi begins at 6.

For the previous school year, there were 18,904 homeschoolers. Homeschooling now makes up about 5 percent of total student enrollment.

The relative ease of homeschooling has helped many families who had never considered homeschooling get started. For a state that has generally shown little interest in education freedom, the freedom to homeschool is broadly supported and protected by law. The one thing a parent must do is file an annual certificate of enrollment with your local school district’s school attendance officer. All you need on the form is your child’s name, address, phone number, and a simple description of the program such as, “age appropriate curriculum.”

When you do that, your child and you are now exempt from the state’s punitive compulsory education laws. There are no requirements on curriculum or testing or who can teach. Parents, instead, have the freedom to choose the educational system, style, and setting that works best for them and their children.

The Department of Education “recommends” parents review state curriculum guidelines and maintain a portfolio of their child’s work, thought that is not required. As opposed to following a government curriculum that tells your child what he or she must learn at what age, homeschooling allows you to let your child learn at their own pace.

That means a child who is excelling can move forward at a quicker pace, cover additional topics, or take in material at a deeper level. If a child is struggling, you can slow down, switch your teaching style, or bring in new materials. If your child has a unique interest, the world is literally at their fingertips with scores of free, online training materials. Yes, YouTube is filled with funny cat videos. But it also provides a library of instruction on virtually any topic you can think of.

Thanks to today’s technology, a quick Google search can help you get more comfortable with homeschooling. There is an abundance of homeschool Facebook groups with veterans who are willing to share their ideas on getting started, curriculum, extracurricular activities, maintaining your sanity, and much more. Connection to these groups is also a venue to plan an endless variety of outings and field trips. It won’t take long to realize your child will receive as much “socialization” as you would like.

There are also options such as co-ops, where families gather together and share teaching responsibilities among parents. Similarly, we have seen the emergence of microschools this year in which a small group of parents pool their resources together to hire a teacher.

While homeschooling experienced it's biggest one-year jump ever, the number of students attending government schools fell from just under 466,000 last year to 442,000, a drop of over 5 percent. This is the eighth straight year that enrollment has decreased since a peak of almost 493,000 for the 2012-2013 school year.

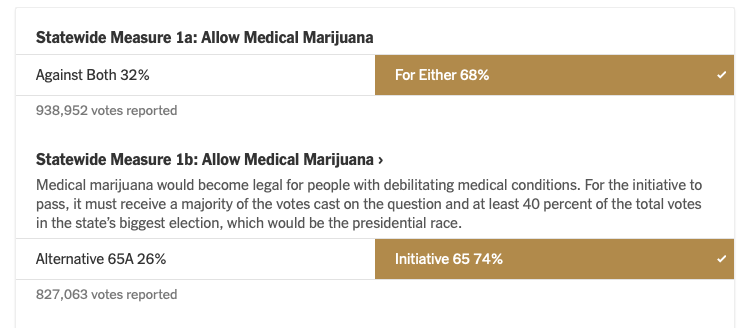

Mississippi voters overwhelmingly approved a medical marijuana ballot initiative on Tuesday while rejecting the more restrictive measure from the legislature. Mississippi will soon become the 35th state with a medical marijuana program.

With over 60 percent of the vote in Wednesday morning, 74 percent of voters chose Initiative 65, the citizen-sponsored ballot initiative. This was the second part of a two-step process because of the legislative alternative. In the first question, 68 percent said “for either.” If a majority had said “against both,” the initiative would have died regardless of the second question.

As written in the initiative, the Mississippi Department of Health will be responsible for developing regulations for the program by July 1, 2021. Medical marijuana patient cards will need to be issued by August 15, 2021.

Here is how the process will work.

Step 1

A person must have a debilitating medical condition. The term “debilitating medical condition” is defined in the proposal as one of 22 named diseases, plus there is a special allowance for a physician to certify medical marijuana for a similar diagnosis.

Some of those conditions include:

- Cancer

- Epilepsy and other seizure-related ailments

- Huntington’s disease

- Multiple sclerosis

- Post-traumatic stress disorder

- HIV

- AIDS

- Chronic pain

- ALS

- Glaucoma

- Chrohn’s disease

- Sickle cell anemia

- Autism with aggressive or self-harming behavior

- Spinal cord injuries

Step 2

A person with a debilitating medical condition is examined in-person and in Mississippi by a physician. The term “physician” is defined in the proposal as a Mississippi-licensed M.D. or D.O.

If the physician concludes that a person suffers from a debilitating medical condition and that the use of medical marijuana may mitigate the symptoms or effects of the condition, the physician may certify the person to use medical marijuana by issuing a form as prescribed by the Mississippi Board of Health.

The issuance of this form is defined in the proposal as a “physician certification” and is valid for 12 months, unless the physician specifies a shorter period of time.

Step 3

A person with a debilitating medical condition who has been issued a physician certification becomes a qualified patient under the proposal.

Step 4

A qualified patient then presents the physician certification to the Mississippi Department of Health and is issued a medical marijuana identification card.

The ID card allows the patient to obtain medical marijuana from a licensed and regulated treatment center and protects the patient from civil and/or criminal sanctions in the event the patient is confronted by law enforcement officers.

“Shopping” among multiple treatment centers is prevented through the use of a real-time database and online access system maintained by the Mississippi Department of Health.

Medical Marijuana Treatment Centers will be registered with, licensed, and regulated by the Mississippi Department of Health. Each medical marijuana business will have to apply to and be approved by MDH. But there will not be a limit on the number of businesses, allowing for a free market based on demand.

Users would not be able to smoke medical marijuana in a public place and home grow would be prohibited, though it is legal is some other states.

We know the world changes around us on a regular basis. We can order anything we want on our phone and have it delivered to our front door. Well, except for alcohol. We can use that same phone to catch a ride, rather than having to rely on a government monopoly for service.

These are just a couple of the more obvious and more recent changes. But it is up to us to adapt and keep up, and for most of human history we’ve done a pretty good job at that.

So, what has been holding us back? Usually the government, and our permission-based society. This became all the more relevant and all the more noticeable at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Think back to two pressing needs at the time: face masks and hand sanitizer. Empty shelves dotted grocery store aisles. Obviously demand increased, but the private sector can adapt. What was the hold up? Government, specifically the Food and Drug Administration.

Distilleries wanted to produce hand sanitizer, something that makes a lot of sense, but they faced a maze of local and federal regulations before they could begin. And if you want to make a face mask, you must first go through the FDA’s approval process, which can take months. In both cases, the regulations were eased, and manufacturers were allowed to ratchet up production.

But should these and many of our regulations exist in the first place? Yes, we need safety, but we can’t be so inflexible that government red tape blocks production on a needed item during a pandemic. That’s obvious, but there are plenty of other areas where government does not allow us to adapt and does not allow entrepreneurs to put their skills to use.

That is why we need to shift from a permission-based society to a default of permissionless innovation. And it is something we can do in Mississippi, a state that has long trailed the rest of the country when it comes to economic growth. Because too often, government creates the framework, a few enter that field, and then “capture” regulators to make it more difficult for new entrants or technology.

The sharing economy is a great example of this. For decades, government approved taxicabs had a monopoly on the service they provided. They encouraged regulations and worked with local governments to create them. Then ridesharing companies were launched and all of a sudden, they had competition. And the outdated model couldn’t compete with prices, availability, and overall service. Naturally, they went back to government to restrict Uber and Lyft. And local governments like Oxford were happy to comply.

After all, these new people didn’t come to us for permission.

So how can we change that and why is this necessary?

COVID-19 impacted more than our ability to purchase face masks or hand sanitizer. Our education systems, restaurants, retail, airlines, and hospitals have all undergone changes to their business model because of the pandemic. We as a state should be encouraging their innovation, rather than placing roadblocks.

An industry neutral regulatory sandbox offers an opportunity for these businesses to navigate around, and temporarily suspend, problematic rules and regulations, allowing businesses to adapt and compete, based on their own ability and market response rather than their ability to win favor from politicians.

And we need to do this before everyone else.

During an election season, you are bound to hear politicians make a lot of promises. One of the most common – largely because it polls very well – is free, or at least cheaper, health insurance. Regardless of the costs and practicality of such claims, there are reforms that would accomplish what we all want: lower costs and greater access.

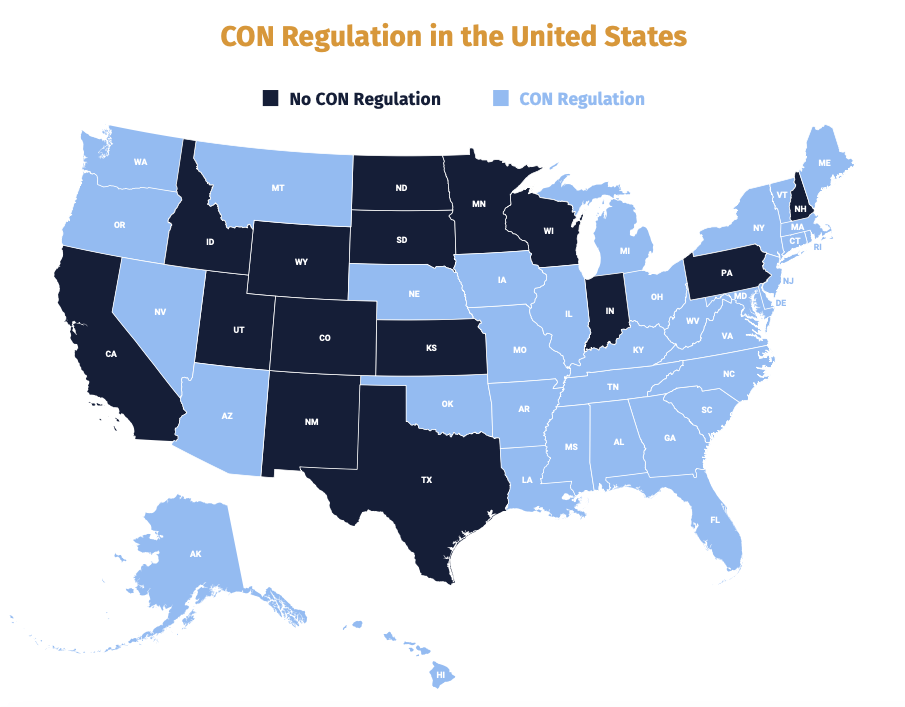

Mississippi is one of 35 states that prohibit entry or expansion of healthcare facilities in the state without permission from the government and your competition through what is known as Certificate of Need laws. Meaning, you can’t just open a new business, or expand your current operation; you need the government’s blessing.

Mississippi requires CONs within five broad categories: hospital beds, beds outside hospitals, equipment, facilities, and services. Mississippi has 80 CON requirements, 41 of which apply to facilities and buildings. And applications range from $500 to $25,000, to start or grow a business.

If this happened in any other area of our economy, you would say that is ridiculous. And you’d be right.

CONs are a product of the 1970s. At the time, the federal government began requiring states to adopt CONs in exchange for federal funds. Some things never change. But the federal government soon learned they didn’t work, and it backtracked, repealing the federal mandate. Thirty-five years later, though, most states are still addicted to this failed government planning.

Which is unfortunate because we have plenty of research showing CONs don’t do what was initially sold. In fact, they actually hurt healthcare outcomes. Let’s look at three claims according to a gathering of research from the Mercatus Center at George Mason University:

- CONs were created to ensure an adequate supply of healthcare resources. That hasn’t happened. Instead, the regulations limit the establishment and expansion of healthcare facilities. CONs are associated with fewer hospitals, ambulatory surgical centers, dialysis clinics, hospice care facilities, and fewer hospital beds.

- CONs were also supposed to ensure access to healthcare in rural communities. We’ve heard plenty of rural hospitals closing in Mississippi, before and after Obamacare. But we know CON programs are associated with fewer rural hospitals, rural hospital substitutes, rural hospice care, and residents in CON states have to drive farther to obtain care than residents in non-CON states.

- And they were supposed to lead to a lower cost for healthcare services. They might reduce overall spending by reducing the quantity of service that patients consume, but the evidence shows that overall CON laws actually increase total healthcare spending.

That is part of the reason we have seen bipartisan opposition from both Republican and Democratic administrations.

In 2004, under President George W. Bush, the Federal Trade Commission and Department of Justice, issued a report saying, “States with Certificate of Need programs should reconsider whether these programs best serve their citizens’ health care needs. The [agencies] believe that, on balance, CON programs are not successful in containing health care costs, and that they pose serious anticompetitive risks that usually outweigh their purported economic benefits. Market incumbents can too easily use CON procedures to forestall competitors from entering an incumbent’s market.”

In 2016, under President Barack Obama, the same two agencies issued a joint opinion, saying, “After considerable experience, it is now apparent that CON laws can prevent the efficient functioning of health care markets in several ways that may undermine those goals.”

Only two states have repealed their CON laws in the past two decades. The proponents of such laws are loud and powerful and are clearly able to garner support from both Republicans and Democrats at the state level.

Then the coronavirus pandemic hit.

Think back to March, and even today in Mississippi. We are worried about hospital beds. We have a new executive order from Gov. Tate Reeves holding hospital bed space. The first reaction from numerous states was to temporarily suspend all or at least parts of CON laws because of the demand caused by COVID-19. This happened in 24 states, but not Mississippi.

So during a health pandemic, what did most states do? Repealed CON laws. Which leads to the next question: why do we have CON laws to begin with? If these regulations, which are promoted as being necessary for our “health and safety,” are not good or helpful during a real emergency, we should agree they are not beneficial for us at any time.

By repealing CON laws, we will help improve healthcare access and help ensure we are ready for the next pandemic. It’s the right policy. It just isn’t as sexy as Medicare for All.

This column appeared in the Yazoo Herald on October 23, 2020.

Mississippi has more than 118,000 regulations on the books that impact virtually every area of our life. The issue isn’t just that we have more regulations per capita than any other state in the South. It is that they aren’t reviewed to ensure they are cost effective and not counterproductive.

Last year, legislation was introduced and cleared the House that would have created a pilot program to reduce regulations. Under the proposal, four agencies would have had to review their regulations and reduce those regs 10 percent a year for three years. In three years, they would have been down 30 percent. This would then provide a starting point for future regulatory reductions among other agencies.

But the legislation didn’t make it through the Senate. And then COVID-19 hit.

Pandemic necessitates to regulatory reduction

As the coronavirus began to spread, two of the immediate healthcare concerns revolved around limited access to medical professionals and a fear of being in the same facility of someone who has the virus. After all, we’re supposed to be social distancing. Thankfully, telemedicine is available to provide you healthcare access in your living room.

To expand access, we began to see states waive the requirement that you can only use an in-state physician in March. Mississippi did that. And then just as quickly walked back that change to only allow this if you have a prior patient-physician relationship, greatly limiting your options as a consumer. Mississippians should be able to access the doctor or nurse practitioner of their choosing, regardless of the state they are licensed and whether or not you have had a previous face-to-face visit.

The same story holds in education. As every school in the state was shut down, an order from Gov. Tate Reeves called for all school districts to adopt distance learning for their students. Six months later this is still a challenge partly because of the rural nature of the state but also because we never had an interest in virtual learning.

Mississippi has a virtual public school, but it’s simply a couple courses a student can take, not a full distance learning program. Every student in the state should have the ability to choose from a plethora of digital options to serve their needs. We are told how hard it is to bring teachers for specific subjects to the most rural or impoverished regions of the state. This could fill that void.

Moreover, virtual charter schools are prohibited in Mississippi’s limited charter law. Some states even have a hybrid mix of homeschool/ charter school facilities where students attend a couple days per week while still doing most of their education at home. Families are able to decide if and what is the best option for their children. Some do a 100 percent virtual program. But not here.

Not only does the data show us that regulations hurt economic growth, but they limited healthcare and education access – two very crucial aspects in the lives of most people – during an international pandemic.

That should tell us something.

Potential next steps?

At the federal level, legislation has been introduced to create a commission that would be tasked with reviewing, and potentially modifying and eliminating regulations. This would serve in many ways like the BRAC commission that was formed at the end of the Cold War to close unneeded military bases. In these instances, politicians are replaced with impartial judges who have a specific mission likely to not be impacted by special interests or electoral concerns.

Mississippi could do something similar. After all, there is general agreement that rules and regulations need to be changed or deleted. The problem is just doing it. Because with every rule is a special interest group or government bureaucracy that likes it.

Mississippi could also move to true sunset provisions on regulations. That is what exists in Idaho and helped the state become the least regulated state in the nation. In 2019, the Idaho legislature essentially repealed their entire state code book when the legislature adjourned without renewing the regulations, something they are required to do each session because the state has an automatic sunset provision. The governor was then tasked with deciding which regulation the state actually needs. With this, the burden on regulations now switches from the governor or legislature needing to justify why a regulation should to be removed to justifying why we need to keep a regulation.

We know regulatory reform is needed. And there are plenty of paths the legislature can follow. It’s just a matter of doing it.

Virtually every year, the regulations and licenses governing many occupations in Mississippi, and throughout the country, only seem to grow.

In the 1950s, about five percent of workers needed a license to work. Today, it is 19 percent of workers in Mississippi.

And as new licenses have been added to the books in Mississippi, it is safe to assume that each proponent, usually an occupational licensing board, made the same central argument: we must do this in the name of consumer safety to protect individual citizens.

The reality is often something less altruistic.

Mainly, these occupational associations are more interested in building a moat around their industry with the help of government. The harder it is for someone to enter an industry, the less competition and consumer choice the industry incumbents face.

This is the story of Dipa Bhattarai, a graduate student at Ole Miss. She had her eyebrow threading business shut down by the state because she lacked the proper license and was forced to lay off four employees.

To re-open her business, she would need to take 600 hours of classes and pass two exams. Yet, not a single hour of classes covers eyebrow threading. Bhattarai and other threaders are required to spend thousands of dollars to learn nothing they want to learn and everything they don't.

But what else can we do?

Source: Institute for Justice

Despite rhetoric from industries on how necessary such regulations are, there are options beyond licensing requirements that do not involve the government. As outlined in a report from the non-profit Institute for Justice, there are voluntary or non-regulatory options that help entrepreneurs start and run businesses while providing the maximum options for consumers.

This begins with market competition, the least restrictive option. Without government imposed restrictions, consumers have the widest assortment of choices, thereby giving businesses the strongest incentives to maintain a reputation for high-quality services. When service providers are free to compete, consumers can decide who provides the best services, thereby weeding out those that do not.

Quality service self-disclosure is a fancy term for customer satisfaction. Think about all the common sites people can leave reviews such as Yelp, Google, Facebook, specific industry sites, etc. Finding out which location is providing a good customer experience is easier than ever, providing users with more complete options.

Voluntary, third-party certification allows the provider to voluntarily receive and maintain certification from a non-government organization. One of the most common examples is the National Institute for Automotive Service Excellence (ASE) designation for auto mechanics. No mechanic is required to receive this certification, just like you may or may not care if a mechanic has it hanging on their wall. But it sends a signal to the consumer that the location with that designation is committed to quality service.

Voluntary bonding and insurance is the final voluntary option. By being bonded and insured, providers are showing their concern for quality to customers at the risk to their own bottom line – whether that’s through the potential for increased premiums or loss of collateral. (If you’re a fan of government, but want a better option than licensure, you can make bonding and insurance mandatory.)

But after reviews or certification, this is essentially another layer of protection for the consumer.

You may or may not care about reviews, certification, bonding, or insurance. Or it may signal to you that this service provider has gone a step beyond to ensure high quality service, but those decisions are driven by market forces, outside of the government.

If you still insist on the government playing a role, there are a number of options that are less restrictive, and therefore better, than government licensure.

Two legal options are private causes of action, which give consumers the right to bring lawsuits against service providers who are at fault, and deceptive trade practice acts, which allows consumers to sue businesses for practices that are deceptive or unfair.

The government can also mandate inspections as they do in a number of fields, most notably the food-service industry. It could be applied in occupations that also require licensing, such as the construction field and barbers and cosmetologists. This allows those who are trained in a field to spot potential hazards, while being less burdensome to licensure. After all, should a contractor be required to have a license if you are going to have an inspection from a trained individual who will tell you if the house the contractor built is about to fall down?

The state may choose to require registration, as they do with hair braiders. Hair braiders previously needed to take hundreds of hours of irrelevant cosmetology classes. Now they register with the state and pay a small fee. This discourages “fly-by-night” providers, while still only creating a small barrier for providers.

All of these options have one theme in common: they are better than government mandated licensure. We do not need to force entrepreneurs to take state mandated classes, pay hundreds (or thousands) of dollars in classes, and take time out of their life to receive permission from the state to earn a living.

Instead, the state can protect consumers, while relying on a small government approach that promotes competition and consumer choice. This is what will encourage economic growth in a state that badly needs it.

It is simply a matter of who you trust more, the government or the individual.

A little more than two years after sports betting came to life in Mississippi, you will soon be able to place a wager on sports in Tennessee. But it comes with one major distinction: All bets will be conveniently placed online.

Sports betting is now expected to begin in November in the Volunteer State. The Tennessee Lottery's Sports Wagering Committee approved the first three operators in the state. There is no cap on the number of sports books in the state.

In Mississippi, the state has seen a bounce back in numbers since sports were shut down earlier this year. Last month, the state saw about $3.7 million in taxable revenue as gamblers and fans welcomed sports back.

Mississippi was at the leading edge of allowing residents to place bets on sports following a 2018 Supreme Court ruling overturning the federal ban on sports betting in every state outside of Nevada. Mississippi had already passed pre-emptive legislation that would legalize sports betting should this ruling occur. As a result, in 2018, Mississippi was the only state in the Southeastern Conference footprint where legal sports betting was available.

But much like casinos, competition has emerged that will continue to limit revenue in Mississippi. Arkansas has had sports betting for more than a year and Tennessee is now coming on board.

The biggest weakness is Mississippi’s requirement that you must be in a casino to place bets, which greatly limits the pool of those who will legally bet. It may be a boom during peak times, such as the Super Bowl or March Madness, but generally speaking a person in Jackson isn’t going to drive to Vicksburg to place a bet on a random baseball game in July. They will continue to bet illegally because bookies are not going to disappear overnight.

While Mississippi made a positive first step in being ahead of the curve, all of the data shows that states need to create an avenue for individuals to bet online to generate the most revenue. In 2019, New Jersey received five times the revenue from online sports betting as they did from retail betting venues.

To continue to see revenue growth for the state from sports betting, Mississippi should follow Tennessee, who doesn’t have casinos, in permitting sports betting online or via an app if you are in the state rather than requiring an individual be in a casino to bet. If we don't, we're limiting the market and leaving money on the table.

A food truck in Tupelo whose work helps fund disaster relief efforts is expanding to a brick-and-mortar restaurant in town.

Jo’s Cafe, a food truck, opened about three years ago. The operation is a faith-based organization principally focused on providing disaster relief to those whose lives have been affected across the United States. Business has been good and they recently made the decision to open a brick-and-mortar restaurant not far from the corner of Gloster and Main Streets.

This is interesting, not in that a food truck is growing and needs to open a restaurant, but in that just two years the Tupelo city council tried to run food trucks out of town. Ironically, at the behest of brick-and-mortar restaurants.

For more than a year, the city of Tupelo debated food truck regulations. In the end, Tupelo did the right thing and never followed through on early regulatory proposals such as what streets you could be located or how far you must be from a brick-and-mortar restaurant.

Why did Tupelo need the proposed regulations? Were people who visited food trucks becoming ill? Did they hate their food? Hardly.

Tupelo Councilman Willie Jennings said, in proposing the regulations at the time, “I just want to make sure the established businesses are protected.” Another councilman, Markel Whittington, said brick-and-mortar restaurants have requested food truck regulations. While he didn’t feel food trucks posed a “threat” to those restaurants, he believed it was appropriate for government to act “on behalf of select business interests.” Hint: It’s not.

Councilman Mike Bryan lobbied for brick-and-mortar restaurant protections, such as a ban on major roads. “I feel like it is not fair to brick-and-mortar businesses to allow food trucks to park in front of their business,” Bryan said. Another councilman, Buddy Palmer, also indicated his support for a ban. “I will always be pro-downtown businesses over food trucks,” Palmer said. “I am for brick-and-mortar businesses much more than I am for food trucks.” Or you could just support new business coming to your city and letting consumers decide?

In Columbus, it wasn’t the government but the proprietor of a local CJ’s Pizza that called the owners of the shopping center where his restaurant is located and had a food truck removed from the parking lot. After all, it was too close to his establishment. “If you think you’re gonna park a food truck right next to my restaurant in the same parking lot and poach my customers then think again,” the rant read on Facebook.

This isn’t how business works. You can’t just run your competition out of town. You provide better food, better service, or a better price, preferably all three. And then the competition closes shop because they can’t survive.

Food trucks are examples of entrepreneurs responding to market signals. In so doing, they are contributing to the local economy by serving a customer niche. Brick-and-mortar restaurant entrepreneurs can do the same, and many have. All of these entrepreneurs, new and old, are creating unique options and working to build a more diverse and appealing food marketplace in Tupelo, Columbus, or wherever they are located. In turn, this attracts more consumers to the downtown – creating a bigger, healthier and more prosperous local economy.

In a properly functioning economy in America, the success of a food company should be based on how good the food and service is; not on how well connected it is to the political class. In a system of capitalism, competitors respond to consumer trends with innovations and improved offerings, not by seeking government help to build a moat around their businesses. We should be encouraging entrepreneurs and risk-takers, not creating hurdles out of a misplaced sense of obligation to protect existing businesses.

It is not the role of government to protect any business, brick-and-mortar or otherwise, from competition. The free enterprise system operates correctly when consumer choice, not political blessing, is the basis of choosing the winners and losers. As we’ve seen during the pandemic, needless regulations only get in the way of consumer choice. That might be healthcare regulations restricting your access to telemedicine. Or your ability to choose what you would like to eat.

Kudos to Tupelo for getting it right and congratulations to Jo’s Café. That should be our goal as a state. To see small businesses grow and get bigger. We would see this more often if only government wasn’t in the way.

Mississippi is the most regulated state in the South.

In 2018, as part of a national review of state regulations, the Mercatus Center at George Mason University found Mississippi has nearly 118,000 regulatory restrictions on the books. All told, the state code book includes 9.3 million words, and it would take about 13 weeks to read if all one did was read regulations as a full-time job.

The biggest regulator in Mississippi, by far, is the Department of Health, with more than 20,000 restrictions. Coming in second is the Department of Human Services, with over 12,000 restrictions. Various state boards, commissions, and examiners have a combined 10,000 restrictions.

But these are simply numbers, what does it look like in real life?

- If you are an eyebrow threader like Dipa Bhattarai who learned how to thread as a young child growing up in Nepal, you must still complete 600 hours of instruction to become an esthetician, even though the classes don’t actually cover eyebrow threading.

- Cosmetologists like Wendy Swart and Dana Presley who were trained and licensed in other states can’t work in Mississippi because we don’t recognize their out-of-state occupational license even though they never had an infraction.

- Entrepreneurs like Donna Harris who want to start businesses to provide weight loss advice, healthy recipes, and grocery list recommendations can be sent to jail for six months and fined $1,000 if they don’t complete 1,200 hours of unnecessary training.

- Cottage food operators who would like to sell food they make at home are limited in what they can sell, how they can sell it, and what they can earn.

- Nurse practitioners who would like full practice authority must enter into a collaborative agreement with a physician if they would like to open their own clinic.

- Liquor stores are required to deal with product shortages because the state controls the distribution of alcohol and can’t keep up with supply. And consumers can’t purchase alcohol online and have it delivered to their front door because we are one of the few states where direct shipment remains illegal.

- If you would like to start a home-based business, many cities in Mississippi prohibit you from hiring employees who don’t live in the house and have vague capacities on how much space in your house you can use for your business. And you’ll have to pay a bookkeeping fee.

- Farmers like the Bailey’s and Beal’s can’t sell raw cow milk to willing consumers. We can sell goat milk, but you can’t have 10 or more goats and you can’t advertise online. And some in the legislature even tried to outlaw that this past session.

- Numerous businesses like the Little Yazoo Sports Bar & Grill were shut down during the pandemic and then only allowed to open at limited capacity.

- Those who want to rent out a room or their house on Airbnb or similar websites are often restricted by local government ordinances.

- We don’t allow small poultry producers to sell to grocery stores, restaurants, hotels, hospitals and other institutions even though the federal government has said it's fine.

- If you would like to start a healthcare business or just expand your current operation, you likely need permission from the state – and your competitors – in what is known as a Certificate of Need before you can proceed.

- We can bet on sports, but only in casinos. We can’t place bets on our phones or computers as most prefer.

While Mississippi is the most regulated state per capita in the South, it is also one of only two states (the other being Louisiana) not seeing population growth in the South.

Mississippi had a negative domestic migration rate of 3.6 last year, meaning for every 100 residents that moved to Mississippi last year, 103.6 left, according to analysis of Census numbers from the Illinois Policy Institute. Louisiana had a negative rate of 5.5. Every other southern state, south of Virginia, had positive numbers. Some smaller like 0.8 in Arkansas, some larger like 10.3 in South Carolina.

So, people aren’t leaving the South, or running for liberal policy (see California, Illinois, and New York), they are just leaving Mississippi. And this trend has been going on for five years.

We can look at Mississippi and say things like, “we don’t have any cool large cities today that people want to move to.” But honestly, were Salt Lake City or Raleigh or Nashville that cool 30 years ago? They certainly looked and performed much differently than they do today.

People moved to those places because of opportunity. And there are policies the state can adopt that would put Mississippi ahead of the curve when it comes to national policy and position the state to be competitive nationwide. And it begins with moving away from a desire to overregulate commerce and embolden government bureaucrats.

Because of federalism, we can look at the templates from other states. And if we’d like to be successful, we can follow the model of our high growth, low regulation neighbors.

But before we can grow, we need opportunity. Not more government.