Last week, Americans celebrated Thanksgiving with family, turkey, football, and – more likely than not – shopping. Early reports show that Americans began the official 2019 holiday season with record retail purchases.

And while a great deal of the focus will be the continued shift away from brick-and-mortar to digital, we can also use the time to acknowledge the best news: it is easier than ever to purchase common household goods.

Did you purchase a television on Black Friday? Today, TVs are universal, and if you don’t have one it is likely because you made the conscious decision not to have a TV in your house, not because you can’t afford it.

That’s because TVs, like most commonly owned goods, have declined dramatically in price. A 23” color TV in 1968 cost $2,544 (in 2018 dollars). Based on the average hourly wage in the manufacturing sector, also in today’s dollars, it would take 125 hours of labor to afford that purchase. Last week, 32” smart TVs were available for $99, or less than 5 hours of labor. And this doesn’t take into account the technological advances of TVs in 2019.

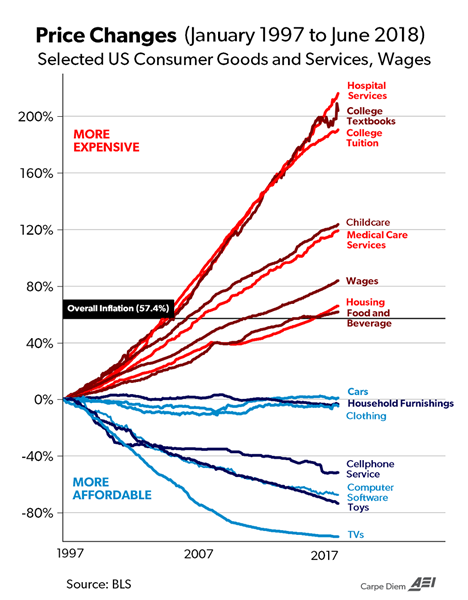

When we see stories about wages being stagnant or new generations being worse off than their parents, we miss one very important item: purchasing power. Yes, government regulated items like education and healthcare have increased much faster than inflation, yet that’s not true of most consumer goods, as shown in the chart below.

We have the ability to purchase more items, and we are likely buying items of greater than quality.

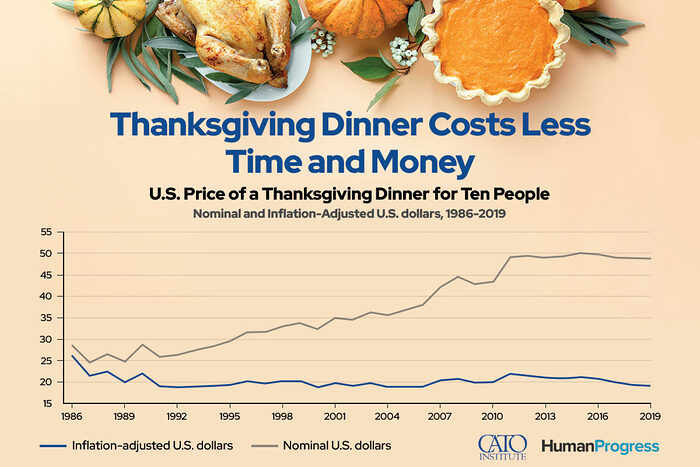

Need something else to be thankful for? The cost of your Thanksgiving dinner slightly declined from the past year, continuing a 30-year trend.

“The main course on many Thanksgiving tables, the turkey, costs slightly less than last year,” a new story from Human Progress found. “In 2019 the average nominal cost of a Thanksgiving turkey stands at $20.80 for a 16-pound bird. That’s roughly $1.30 per pound, a 4 percent decrease from last year. And that’s before adjusting for inflation!”

And if you traveled last week, you’ll also be happy to know that air travel continues to get safer.

Our well-being is improving, and it’s expanding to more and more Americans. Something we rarely hear about, or talk about. Maybe we should.

The Mississippi Hemp Cultivation Task Force voted Wednesday to approve the release of their final report to the legislature on December 2.

The task force says in the executive summary that while there is both positive potential and significant risks for hemp cultivation in the state, there could be additional costs for taxpayers.

Mississippi is one of only three states where hemp cultivation is illegal and the legislature could take up the issue in January, when it returns to Jackson for the annual regular session. The task force’s report was designed to give the legislature information on how to craft legislation on legalizing hemp cultivation.

Hemp is derived from strains of the cannabis sativa plant with low amounts (0.3 percent content or less) of the psychoactive substance in marijuana known as THC. The plant can be cultivated for its fiber, which can be used in insulation, rope, textiles and other products.

The seeds are also a good source of protein and can be eaten by humans or used for animal feed. The flowers of the plant can be used for cannabidiol, or CBD oil production with possible benefits still being studied by scientists nationally and at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

One of the roadblocks for Mississippi hemp cultivation cited by the task force is nearly gone after the U.S. Department of Agriculture presented a draft of regulations on October 31. These new rules govern hemp cultivation nationally after the 2018 U.S. Farm Bill authorized the growing and sale of hemp.

The comment period for the draft rule closes on December 30.

In addition to legislation, Mississippi officials would also have to submit a hemp cultivation plan to the USDA for approval before hemp could be grown in the state.

The problems the task force’s report spotlighted with hemp cultivation include:

- Current oversupply of hemp in the market.

- Lack of infrastructure and supply chain to get the products to market.

Mississippi Agriculture Commissioner Andy Gipson said licensing fees in the 47 other states that legalized it for commercial, research, or pilot programs hasn’t been enough to cover the costs related to regulation, such as hiring new personnel and testing.

He said those type of costs have added up to $500,000 in additional spending in Kentucky, a state Gipson said is the most advanced nationally in its hemp cultivation program.

Mississippi law enforcement agencies lodged the same complaints in the draft report as they have throughout the process. These concerns include:

- Inability to distinguish between hemp and marijuana on the side of the road.

- Law enforcement officers would be unable to conducts arrests and prosecutors would be unable to prosecute marijuana cases.

- A backlog at the Mississippi Crime Laboratory of 400 exhibits per month.

- It would cost $500,000 for the crime lab to perform THC chemical analyses.

According to Gipson, the state’s crime lab meets federal standards for drug testing.

Kentucky could be a model for Mississippi. Since the first pilot program launched in 2014, the number of planted acres has grown from 33 to 6,700 and the number of approved growers have increased from 14 at the program’s inception to 978 in 2019.

State law requires licenses for growers and processers, which include background checks. They also have to consent to inspection by program officials and law enforcement at any location where hemp or related products are grown, handled, stored or processed. Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates have to be provided to the Kentucky Department of Agriculture before hemp is planted.

Lottery tickets will go on sale next week in Mississippi a short 15 months after the legislature legalized a state lottery in the 2018 special session.

Mississippians will be able to purchase scratch-off tickets beginning on November 25 at one of more than 1,200 retailers statewide. Power Ball and Mega Millions tickets, the multi-state games known for big payouts that have at times surpassed $1 billion, will go on sale later in 2020.

But you need to be older in Mississippi than most other states to purchase lottery tickets. The minimum age is 21. Arizona, Iowa, and Louisiana are the only other states that require you to be 21 to buy tickets. You have to be 19 in Nebraska. Every other state sets 18 as the age minimum.

That includes Arkansas and Tennessee. Mississippi’s other neighbor, Alabama, is one five states that do not have a state lottery.

The bulk of lottery profits in Mississippi – the first $80 million – will be directed toward infrastructure projects. Additional money will go toward education, which is traditionally the primary funding recipient from most lotteries.

Mississippi took a long and windy road toward a lottery

In 1992, voters in Mississippi cleared the way for a lottery by amending the state constitution to allow for a lottery, but there was little interest from the legislature over the next two plus decades. Especially with the creation of casinos along the Coast and Mississippi River and the revenue that gaming promised.

But that changed in 2018. For years, stories regularly ran of Mississippians crossing state lines to purchase lottery tickets as jackpots crept up. Popular support appeared to be on the side of a lottery. Many Republicans were outspoken in their support. And Gov. Phil Bryant came out in favor of a lottery and it became a solution for more transportation funding. And in August of last year, the legislature legalized a lottery in Mississippi.

But even that wasn’t easy. The House initially voted against the lottery conference report in a bipartisan vote of 61 opposed and 53 in favor. Legislators got another stab at it and it passed the House 58 to 54 on the second vote. It was an odd-looking board with the speaker and speaker pro tempore voting against it, but in the end the bill was adopted.

And Mississippians will soon be buying lottery tickets. If they’re 21.

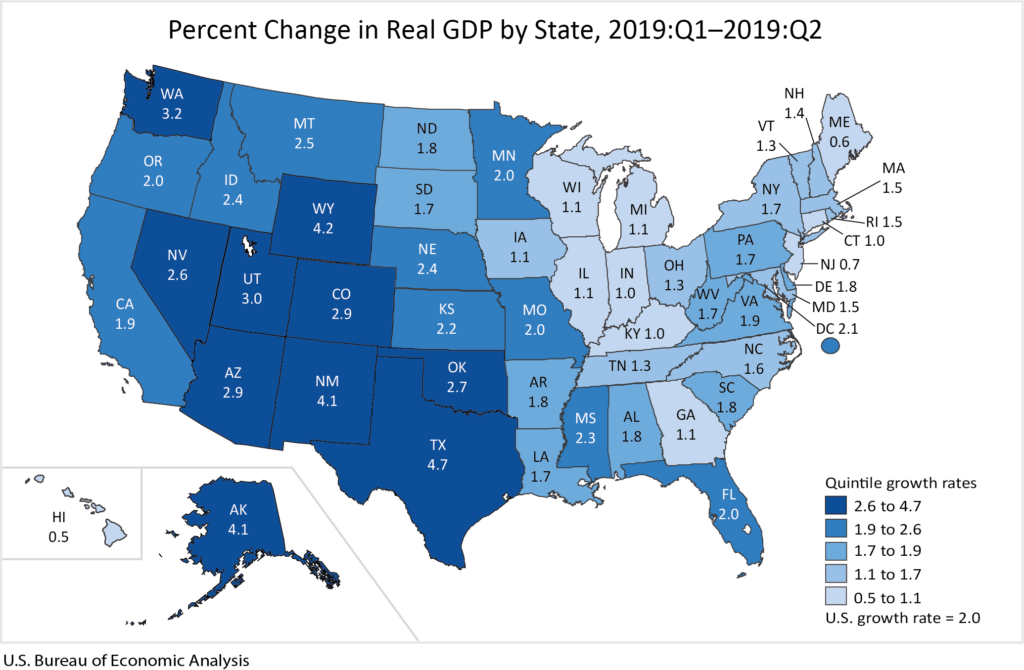

Mississippi’s real gross domestic product outpaced the national and Southeastern average for the second quarter of 2019.

Mississippi’s GDP grew by 2.3 percent compared to the first quarter of the year. This was part of a national trend that saw growth among all 50 states. The national average was 2 percent and the Southeast average, which does not include Texas, was 1.7 percent. Texas posted the strongest numbers in the country at 4.7 percent.

Professional, scientific, and technical services and real estate were two of the leading contributors to the GDP growth. Mississippi’s numbers, however, were below others in both sectors. Mining, which helped many western states see big gains, increased by 23.5 percent nationally.

A look inside Mississippi’s numbers reveals noticeable positives for the state, and areas that need improvement.

- Mississippi outpaced the Southeastern average in agriculture (and related industries), utilities, construction, durable goods manufacturing, retail, and finance.

- Mississippi trailed the Southeastern average in real estate and professional, scientific, and technical services.

- While wholesale trade was down nationally, Mississippi saw smaller loses than Southeastern and national numbers.

- Mississippi had the 3rd highest growth in government, behind only Maryland and New Mexico.

- Mississippi’s percentage of the U.S. GDP has been 0.6 percent for the last six quarters.

Percentage change in GDP, Southeast states

Mississippi led every Southeastern state in change of GDP. Florida was the only other Southeastern state above 2 percent. Kentucky had the lowest change, with a growth rate of 1 percent.

| State | Change | Rank |

| Alabama | 1.8 | 26 |

| Arkansas | 1.8 | 25 |

| Florida | 2.0 | 17 |

| Georgia | 1.1 | 44 |

| Kentucky | 1.0 | 46 |

| Louisiana | 1.7 | 29 |

| Mississippi | 2.3 | 14 |

| North Carolina | 1.6 | 32 |

| South Carolina | 1.8 | 23 |

| Tennessee | 1.3 | 38 |

| Virginia | 1.9 | 21 |

| West Virginia | 1.7 | 27 |

In the first quarter of 2019, Mississippi’s GDP grew by 1 percent compared to the Southeastern average of 2.6 percent.

Today’s technology has helped usher in what is commonly referred to as the sharing economy. This is a broad term we use for an economic system where services are provided in exchange for a fee, via a third-party facilitator.

The most common examples of the sharing economy are ridesharing and homesharing apps, such as Uber, Lyft, Airbnb, or HomeAway. On the surface, escorting people around town in a car or renting out a spare bedroom aren’t exactly technologically advanced ideas.

It is the digital platforms or apps that have centralized the process and provided a certain level of comfort as a virtual middleman that has led to the explosion we are witnessing.

We see this in many other areas of our life as well. Peer-to-peer websites or apps, whether it’s Yelp, Facebook, Google reviews, and others, do a better job of providing feedback to potential customers than any government inspector.

Sure, government grades restaurants, but most people make their decisions on where to eat based on feedback from past customers. If an establishment was dirty, you’d read about it there, rather than from a government grade.

A common example of a profession that depends on positive feedback is home bakers, who are part of the rapidly growing cottage food industry. In deference to the incumbents who have paid a regulatory price, Mississippi limits what you can sell, where you can sell it, and how much you can make before you bow to the government and seek permission.

While many have attempted to warn us of the dangers of cookies or brownies baked at home in a non-government approved kitchen, we can find high-quality food via reviews from happy (or unhappy) customers.

Once again, we’ve always had word of mouth reviews among friends, but technology has helped bring that to the masses, elevated peer reviews, and forced businesses to bring greater attention to customer satisfaction.

In fact, if you suffer from repeated negative reviews, you will no longer be able to rent your house on Airbnb, nor will you be able to drive for Uber.

All of this is occurring naturally, rather than with the help of government. The response from those whose industry has been interrupted is not surprising. But it is unfortunate how government has attempted to intervene in the free market in too many instances.

When Uber first made its way to Mississippi, the reaction from many localities was to enact strict regulations. After all, the taxis had spent years building their industry cartel working alongside government. Now, you had a group doing it without government’s blessing.

One of the most egregious examples of an overzealous government was in Oxford, a college town who has a greater need for this service than most. They coordinated with the local taxi companies on regulations that effectively banned ridesharing options.

Today, Uber and Lyft operate freely in Mississippi thanks to the legislature pre-empting municipalities and opening ridesharing statewide. It is clear that the legislature’s work is not done in supporting consumers and entrepreneurs in the face of local government interference.

A map of current Airbnb rentals is a good indicator of places people want to visit. One might assume those governments would want to welcome visitors, but we have seen Gulfport and Biloxi take adverse actions, with Starkville considering new regulations that would limit the number of nights you could rent your house and enforce a residency requirement.

Meaning, you can’t buy a house and rent it out, something relatively common in a college town with SEC football. The net result would be fewer options for visitors.

The incumbent companies will complain that the playing field isn’t level with the new technologies. If that’s the case, we should regulate down, rather than up. We should make it easier for everyone to do business safely. Yes, it should be easy to rent out your house. Just like it should be easy to open a new hotel.

All of these new technologies are inherently positive. They are positive for the entrepreneur, who may need supplemental income and flexibility with their job so they can pursue an education and/or care for family. Regulating up and making it harder for these services to exist will hurt the people who need jobs the most. And they are a positive for the consumer who now has new options in what they can choose.

This is voluntary exchange and we should be encouraging it.

This column appeared in the Clarion Ledger on November 7, 2019.

Voters in Simpson county on Tuesday approved a referendum that will legalize alcohol sales countywide.

According to unofficial reports, 61 percent of voters supported the referendum, meaning Simpson county will soon become a ‘wet’ county.

Mississippi has a hodge-podge of liquor laws as the 1966 law that repealed prohibition provided for local control over alcohol sales. According to PEER, Mississippi has 31 dry counties, with three additional counties that are partially dry. However, most of those counties have some have localities that have either wet municipalities or resort area status, allowing the legal sale of alcohol.

Throughout Mississippi, there has been a strong move in that direction among dry counties as their numbers continue to dwindle.

Proponents of the referendum in Simpson county submitted the necessary 1,500 certified voter signatures for the referendum this past August. Previous efforts had stalled due to lack of signatures.

Dipa Bhattarai is suing the state so she can have the right to earn a living eyebrow threading without having to take hundreds of hours of irrelevant classes. She's not the only one having to jump through unreasonable hoops. Mississippi is one of the least economically free states according to an annual study by the Fraser Institute.

The Fraser Institute released its Economic Freedom of North America 2019 report Thursday and Mississippi was ranked 42nd with a score of 5.3 out of 10, ahead of only Kentucky, California, New Mexico, Oregon, Vermont, Alaska, West Virginia, and New York.

The study measures economic freedom in terms of three categories: government spending, taxes, and regulations and uses data from 2017, the most recent year data was available for all jurisdictions.

Mississippi ranked 44thin government spending, 36th in taxes and 40thin labor market freedom.

According to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 20.5 percent of those employed in the state in work for a division of government, be it federal, state or local.

This figure outstrips manufacturing, retail, and food services.

The non-partisan Tax Foundation rated Mississippi 31stin its annual Business Tax Climate Index, with the state having the 10thlowest corporate tax rate while having a mid-pack (27th) individual income tax rate. The state’s sales tax was 34th highest in the nation while the property tax rate was 37thworst.

According to the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, the state’s regulations contain 117,558 restrictions and 9.3 million words. It’d take an individual 518 hours (or about 13 weeks) to read the state’s administrative code.

New Hampshire and Florida were the top two states in the Fraser Institutereport, which also uses the same metrics to measure economic freedom in states in Mexico and Canadian provinces.

Mississippi was ranked as one of the “Least Free” among the states by the Fraser Institute’s annual report, a place it has been all but two years since 1998. Mississippi’s 42nd ranking was the same as last year, when Mississippi scored a 5.2 out of 10.

Mississippi’s neighbors are doing much better in the rankings, as Alabama was ranked 35th(5.8 total score out of 10), Arkansas 32nd (6.0), Louisiana was ranked 26th (6.3) and Tennessee was third in the study (7.6).

The study was authored by Southern Methodist University economist Dean Stansel; Caminos de la Libertad head of research Jose Torra and Fred McMahon, who is the resident fellow as the Dr. Michael A. Walker Chair in Economic Freedom at the Fraser Institute.

The Fraser Institute, a Canada-based free market group, has conducted the Economic Freedom of the Worldreport for the last 30 years. The primary conclusion of the reports was that “economic freedom is positively correlated with per-capita income, economic growth, greater life expectancy, lower child mortality, the development of democratic institutions, civil and political freedoms, and other desirable social and economic outcomes.”

In the most-free states and provinces in North America, the average per capita income in 2017 was 9.2 percent above the national average compared to 3.4 percent below the national average in the least-free jurisdictions.

The trend line for economic freedom in the U.S. isn’t positive, according to Fraser Instituteresearch.

From 2003 to 2017, the average score for U.S. states in the all-government index fell from 8.23 to 7.92.

New regulations went into effect today that will allow vegan and vegetarian companies to continue using meat product terms on their labels.

In July, vegan food company Upton’s Naturals and the Plant Based Foods Association (PBFA) filed a First Amendment lawsuit challenging a Mississippi law that would have banned plant-based food companies from using meat product terms like “burger,” “bacon,” and “hot dog” on their packaging. Upton’s Naturals and PBFA were represented by the Institute for Justice and by the Mississippi Justice Institute serving as local counsel.

In August, the parties to the lawsuit advised the court that they were engaging in negotiations that might lead to the adoption of new regulations and the resolution of the case. Those negotiations ultimately led to the withdrawal of proposed regulations that would have implemented the ban, and the adoption of new regulations.

“These new regulations are a victory for free speech in Mississippi,” said Aaron Rice, Director of the Mississippi Justice Institute. “Consumers understand that products labeled with terms like ‘vegetarian burger’ are plant-based foods. Our clients can now continue using labels that are best understood by their customers without risking potential criminal prosecution.”

Under the new regulations, plant-based foods will not be considered to be labeled as a “meat” or “meat food product” if the label also includes “meat-free,” “meatless,” “plant-based,” “vegetarian,” “vegan,” or similar terms.

Because the new regulations adopted in response to the lawsuit will allow companies to continue using meat product terms on their labels, Upton’s Naturals and PBFA have dropped their lawsuit.

The new regulations can be found here.

Mississippi food stamp work requirements have put program participants back in the workforce while reducing the number of residents dependent on government assistance.

A newly recently released report by the Foundation for Government Accountability says that work requirements have also saved taxpayers $93 million since Gov. Phil Bryant restored them in 2015 for able-bodied, childless adults who participated in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, which is also known as food stamps.

Food stamp enrollment, according to the report, began to drop immediately in Mississippi and had fallen by 72 percent by October 2018. The drop isn’t unprecedented, as two states, Arkansas (70 percent reduction) and Florida (94 percent) posted similar numbers after instituting similar work requirements for SNAP.

Also, since 2016, the average amount of time spent in the SNAP program for able-bodied recipients in Mississippi has dropped by 60 percent.

The study shows that work requirements have decreased dependency on taxpayers by able-bodied, childless adults. According to data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, 85 percent of these adults on food stamps weren’t working at all in Mississippi in 2015.

Those former SNAP recipients received jobs in 716 different industries and only 23 percent of them are still working in entry-level jobs such as fast food or retail. Their incomes grew by 64 percent within three months of leaving welfare.

After a year, those incomes increased by 98 percent within a year and 121 percent for those who’d left the food stamp program 18 months before.

“Conservative policies are working, and Mississippi is continuing to reap the benefits of welfare reform,” Bryant said on Twitter. “After implementation of food stamp work requirements we have seen significant improvements.”

Bryant’s administration launched a study to track results of the work requirements, as the Mississippi Department of Human Services worked with the state Department of Employment Security, the National Strategic Planning and Analysis Research Center at Mississippi State University, and FGA to track wages and the industries entered by former welfare recipients.

Up until the mid-1990s, there had been little effort at the national level to end dependence on welfare.

In 1996, then-President Bill Clinton signed into law the Federal Welfare Reform Act. It transitioned a permanent entitlement program known as Aid to Families with Dependent Children to a temporary block grant program known as Temporary Aid to Needy Families or TANF.

The new law also established work requirements for SNAP, which were later watered down as the federal government granted waivers for states to eliminate these rules for some segments of the population.

In 2015, Bryant restored the work requirements by ending the work requirement waiver. Those able-bodied childless adults who met the work requirements could stay on the program, but those who failed the meet the standard were terminated from the program starting in the first quarter of 2016.

More reforms for the state’s welfare system were still to come.

In 2017, Bryant signed into law House Bill 1090, also known as the Act to Restore Hope Opportunity and Prosperity for Everyone. Authored by state Rep. Chris Brown (R-Nettleton), the law required eligibility monitoring for Medicaid, TANF, and SNAP and required the state agencies to share eligibility data. It also enshrined the end of the state’s work requirement for SNAP into state law.

It also mandates that state agencies administering welfare programs verify residency and immigration status and bans the use of the EBT cards at ATMs at liquor stores, strip clubs, casinos, and other questionable businesses.

In 2020, a West Virginia law will rescind the state’s ability to issue SNAP work requirement waivers. Wisconsin also passed a similar law.

Thirty states still have partial time limit waivers for the food stamp program, while Mississippi is one of 17 states that have no waivers.