At Tuesday’s Republican gubernatorial debate, all three Republican candidates for the top office in the state said they oppose the medical marijuana initiative that is ongoing and may be in front of voters in a little over a year.

For various reasons ranging from federal prohibitions to the belief that this is a gateway, Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves, former Supreme Court Justice Bill Waller, Jr., and state Rep. Robert Foster all agreed they were opposed to the initiative.

Waller referenced his time on the court saying, “The last thing we need is another substance that could provide issues.”

He added, “Even in medical use, reports show an increased aggressiveness with the use of it as a gate to other drugs. I am not interested in introducing another drug unless it can be shown there is a void that couldn’t be filled in any other way.”

Reeves is also a no.

“The reason I am is because I have three daughters and see this as a potential gateway drug,” Reeves remarked. “In many areas of our society, drugs are killing people, drugs are ruining people’s lives. They lead to a life of criminal activity. I will personally vote no.”

Foster said he couldn’t support it at this time “because it has not been unscheduled by the federal government.”

While that is true, the U.S. Congress passed a law five years ago that prohibits federal agents from raiding medical marijuana growers in states where medical marijuana is legal, effectively allowing states to legalize medical marijuana as they have done since 1996.

“I don’t want what they have in California and Colorado where they have pot shops on every street corner. If the federal government were to allow it to be sold through pharmacies after a doctor has written a prescription for certain things, then that would be a totally different scenario.”

Medical marijuana is now legal in 33 states and Washington, D.C. And much of the movement has been in the past decade. Just eight states legalized medical marijuana by 2000. But 21 states have acted since 2010. The most recent states to legalize medical marijuana were Missouri, Oklahoma, and Utah, each doing so last fall.

To make Mississippi the 34th state, proponents of a ballot initiative, Medical Marijuana 2020, are hoping to collect enough signatures to have the question on the ballot in November, 2020.

The petition faces a September 6 deadline to submit 86,000 signatures to the Secretary of State. Jamie Grantham, a spokesman for the campaign, said they have collected more than two-thirds of the necessary signatures.

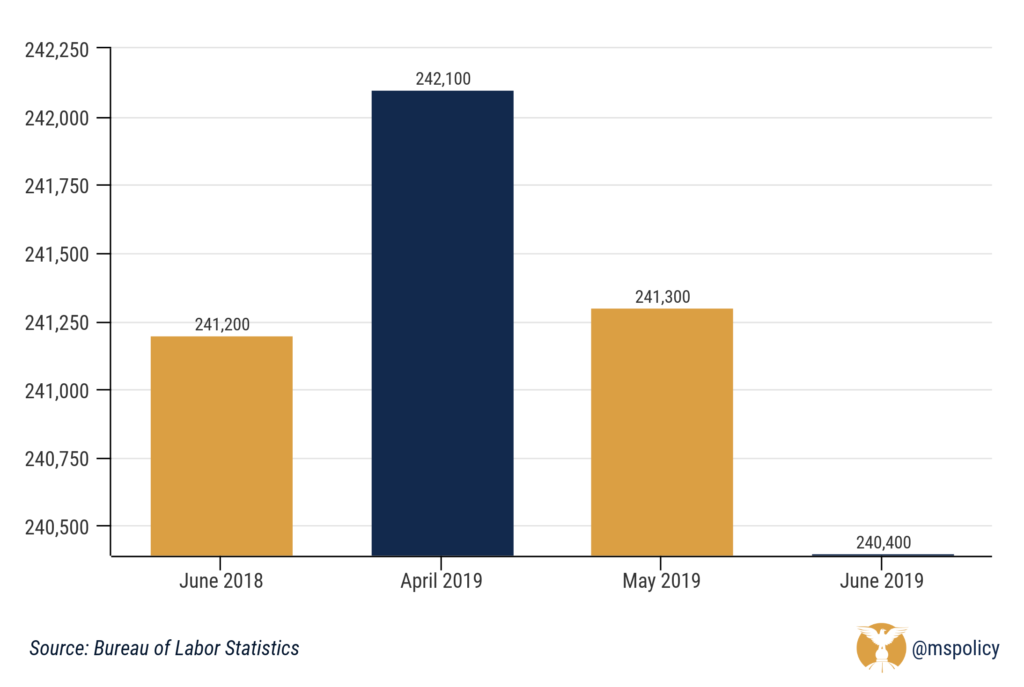

Mississippi has seen a drop in government jobs over the past two months and the government workforce in the state is now smaller than it was one year ago.

In June 2018, Mississippi had 241,200 government employees according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and that number had increased to 242,100 this past April. But after declines the past two months, preliminary numbers show Mississippi has 240,400 government employees as of June 2019. This includes federal, state, and local government employees.

Government jobs in Mississippi, June 2018 through June 2019

At the same time of the loss in government jobs, the private sector has grown. Employment rolls grew by 2,500 in May and another 2,000 in June. Mississippi employers have added 14,000 jobs over the past year. Payrolls in Mississippi now sit at 1,168,100.

When looking just at the state workforce, this continues a trend over the past 15 years even though numbers may fluctuate month-over-month.

According to a 2018 report from the Office of the State Auditor, the number of state government employees has decreased by more than 5,200 dating back to 2004, largely through attrition and voluntary separations. The bulk of the reduction, about 4,500 employees, occurred in the past seven years.

Even with the declines, approximately 56 percent of Mississippi’s economy is controlled by the public sector, putting its reliance on government fourth worse in the nation. To continue to generate sustainable, long-term growth, we need to continue to grow the private sector through lower taxes and a lighter regulatory burden.

Few things could be better on a hot Mississippi summer day than a refreshing glass of ice, cold lemonade. And, if you’re lucky, you might just find a smiling face selling lemonade during your travels.

Lemonade stands are one of the great American traditions. For generations, boys and girls turn into aspiring entrepreneurs making and selling lemonade. The young children are able to earn money, whether it’s for a special toy they have been wanting or to save for a future purchase.

Without even realizing it, the children simultaneously learn valuable lessons. They learn that money comes from work. That you have to plan, and then produce a stand, signs, and lemonade. Introducing kids to the valuable concepts of marketing, costs, customer service, and profit motive.

That’s why the lemonade stand has always been celebrated in our society.

But lemonade stand entrepreneurs began to meet a force that strikes fear in the hearts of even the most seasoned professionals: the government regulator.

By now, you have probably heard the stories, but they bear repeating because of the sheer lunacy of feeling the need to shut down a lemonade stand operated by kids. And because these stories highlight the over criminalization of our society - thanks to laws we have adopted to fix every supposed issue or problem.

In Colorado, three young boys, ages two to six, had their lemonade stand shut down by Denver police for operating without a proper permit. The boys were selling lemonade in hopes of raising money for Compassion International, an international child-advocacy ministry. But local vendors at a nearby festival didn’t like the competition and called the police to complain. When word of this interaction made news, the local Chick-Fil-A stepped up as you would expect from Chick-Fil-A. They allowed the boys to sell lemonade inside their restaurant, plus they donated 10 percent of their own lemonade profits that day to Compassion International.

In Texas, two sisters, seven and eight years-old, had their lemonade stand shut down by the local police, also for lacking the proper permit. The city, kindly, for lack of a better word, agreed to waive the $150 “Peddler’s Permit,” but the young girls would still need an inspection from the health department before they could proceed. The girls were hoping to raise money so they could go to a local water park with their dad, who is often away from home because he works in the oil field, for Father’s Day. The water park and a local radio station donated tickets after hearing the story.

Since these stories, and others like it, we have seen a shift away from the ludicrous. The lemonade stands are fighting back. Common sense seems to have prevailed.

Texas and Colorado have now become two of the first three states to legalize lemonade stands for children. Utah became the first state to pass such a law in 2017. These laws, which have passed with overwhelming, bi-partisan support, allow minors to run “occasional” businesses, such as a lemonade stand, without needing a permit.

If you run into a regulator in a state that doesn’t enjoy such lemonade friendly laws, Country Time Lemonade has launched “Legal-Aide.” For those who receive a fine for operating an unlicensed stand, they will cover your fine up to $300. They also have a handy website that will help you contact lawmakers and get engaged in the fight to legalize lemonade stands in all 50 states.

At the same time, Lemonade Day is national program that has grown considerably in the past several years. Participating cities, including Jackson and cities in the Golden Triangle, give children in the area the opportunity to run a business during a community-wide Lemonade Day.

What these stories have shown is that when the government has overreacted, the private sector has stepped up and provided opportunities for children.

Hopefully, these stories raise more than a few eyebrows. Perhaps they will cause people to recognize the downside of our regulatory burden and maybe even cause legislators to review more than a few of the laws, rules, and licensing regimes that are stifling growth, innovation, and capitalism.

If we want a thriving and growing economy, we’ve got to have more entrepreneurs – including those future ones who sell lemonade in their neighborhoods today.

Tucked quietly in a non-descript beige building in Flowood is one of Mississippi’s best-kept secrets.

Zavation is a company that specializes in design, engineering and manufacturing of spinal hardware and other medical equipment that allows for minimally invasive surgery.

The company was started in 2010 by a pair of University of Mississippi graduates and made its first sale in 2012 despite not receiving any state or local tax incentives. The company released 10 new products in 2018 and recorded its first international sale this year.

Now, Zavation has moved to its third building as its business continues to expand and it employs 60 in its 30,000 square foot facility. Its products are being distributed in 40 states by more than 150 distributors.

Zavation is vertically integrated, meaning that design and manufacturing are all in house. Zavation is also in the process of adding a clean room to its Flowood facility, which will enable it to expand its business to new areas.

Dee Hillhouse, the company’s national sales manager, says vertical integration allows the company to have full quality control and not have to wait on suppliers to ship needed components.

Many of Zavation’s engineers once worked in the aerospace industry, which gives them a unique perspective. The company is able to prototype their new designs in house, as they have their own milling machine reserved solely for prototypes. Using computer-assisted design software, they can feed the specifications to the milling machine so they can start testing and quickly deal with any problems.

The approval process by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration can vary on new products, but a simple product can take up to a year, with a couple of years needed for more complex devices. In June, Zavation received approval to market its new pedicle screw system to immobilize and stabilize spines in patients as part of fusion surgery.

Once the FDA allows Zavation to sell new products, the company uses highly automated milling machines to produce both plastic and metal components for the new product. The Flowood facility has a costly laser etching machine to put serial and lot numbers on every component for quality control purposes and the in-house anodizing machine ensures that the metal is more wear and corrosion resistant.

After automated quality control checks, the components are assembled by workers and boxed for shipping to surgeons nationwide.

Zavation recently acquired a Tampa-based company, Pan Medical U.S. The new combined company will be able to bring a larger range of surgical products to market. The most important of these is the Curveplus kyphoplasty system for spinal procedures.

In a kyphoplasty, a surgeon injects bone cement into fractured vertebra to relieve back pain. Pan Medical has developed the Curveplus that allows both the balloon and cement to be sent through a curved needle, which decreases the number of steps and the overall procedure time.

Never heard of Zavation? That’s because no political photo ops, ribbon-cutting, or silver shovel events were held to celebrate the company’s start-up. Instead, the founders, investors, and early employees went to work to create unique and valuable products to serve a market of need. Rather than rely on government subsidies, contracts, or tax incentives in the name of job creation, Zavation created jobs as a result of creative disruption, innovation, marketing, and sales.

After touring the impressive facility, it’s clear the company is well-run with a strong focus on process management. In short, Zavation is a great example of the kind of economic growth that can come from small, private companies and entrepreneurs.

This is what happens in healthy economies. Entrepreneurs and capital find each other and a small company grows into a big one, without the direct aid of government. We need more examples like Zavation in Mississippi.

If we want long term, sustainable economic growth in Mississippi, we need the private sector to blossom and government’s role should be to create an environment that allows the free market to function at maximum capacity. We don’t need our government to pick our winners and losers for us. They are not equipped to outperform the market, no matter how noble their intentions.

Mississippi Center for Public Policy has joined a diverse coalition in publishing a set of seven principles to guide conversation about amending Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996.

The coalition includes civil society organizations, academics, and other Internet law experts.

In its current form, the law holds those who create content online responsible for the content they create, while protecting online intermediaries from liability for content generated by third parties, except in specific circumstances.

Maintaining that fundamental arrangement is vital. As the principles statement declares: “We value the balance between freely exchanging ideas, fostering innovation, and limiting harmful speech. Because this is an exceptionally delicate balance, Section 230 reform poses a substantial risk of failing to address policymakers’ concerns and harming the Internet overall.”

As civil society organizations, academics, and other experts who study the regulation of user- generated content, we value the balance between freely exchanging ideas, fostering innovation, and limiting harmful speech.

The seven principles are:

- Content creators bear primary responsibility for their speech and actions.

- Any new intermediary liability law must not target constitutionally protected speech.

- The law shouldn’t discourage Internet services from moderating content.

- Section 230 does not, and should not, require “neutrality.”

- We need a uniform national legal standard.

- We must continue to promote innovation on the Internet.

- Section 230 should apply equally across a broad spectrum of online services.

Read the full letter here.

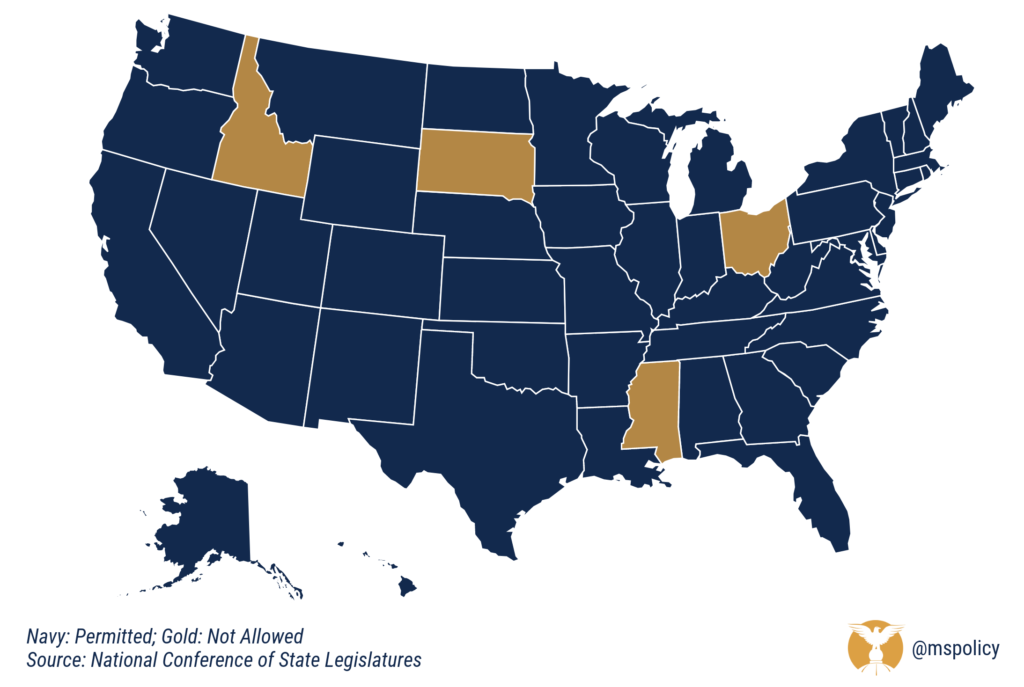

As the Hemp Cultivation Task Force kicks off their work, Mississippi now finds itself on an island as the only state in the Southeast where the cultivation of hemp is illegal.

This year, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas joined the ranks of states legalizing industrial hemp. As states continue to move in that direction, Mississippi is sitting with just Idaho, Ohio, and South Dakota among the only states in the nation where hemp remains illegal.

The South Dakota legislature Ok’d hemp legalization earlier this year, but it was vetoed by Gov. Kristi Noem.

Cultivation of hemp for commercial, research, or pilot programs

We have seen a massive move toward hemp legalization at the state level after the 2018 Farm Bill expanded the cultivation of hemp. Previously, federal law did not differentiate hemp from other cannabis plants, even though you can’t get high from hemp. Because of this, it was essentially made illegal. But we did have pilot programs or limited purpose small-scale program for hemp, largely for research.

Now, hemp cultivation is much broader, with the Farm Bill allowing the transfer of hemp across state lines, with no restrictions on the sale, transport, or possession of hemp-derived products. There are still limitations, but most states have taken the opportunity to find new markets for those who would like to cultivate hemp.

The message from Marshall Fisher, the commissioner of the Department of Public Safety, at yesterday’s first meeting of the task force was that we can’t do this. It’s not regulated enough, there is a link between hemp and fentanyl, and we will see more people being buried if we move in this direction. And law enforcement can’t tell the difference between hemp and cannabis.

We don’t know what the task force will recommend. It includes both supporters and opponents. And of course, the legislature – who will be tasked with acting on any recommendations – will be different next year.

But, if we have questions on whether or not hemp leads to chaos in the streets, we can just look to 46 other states.

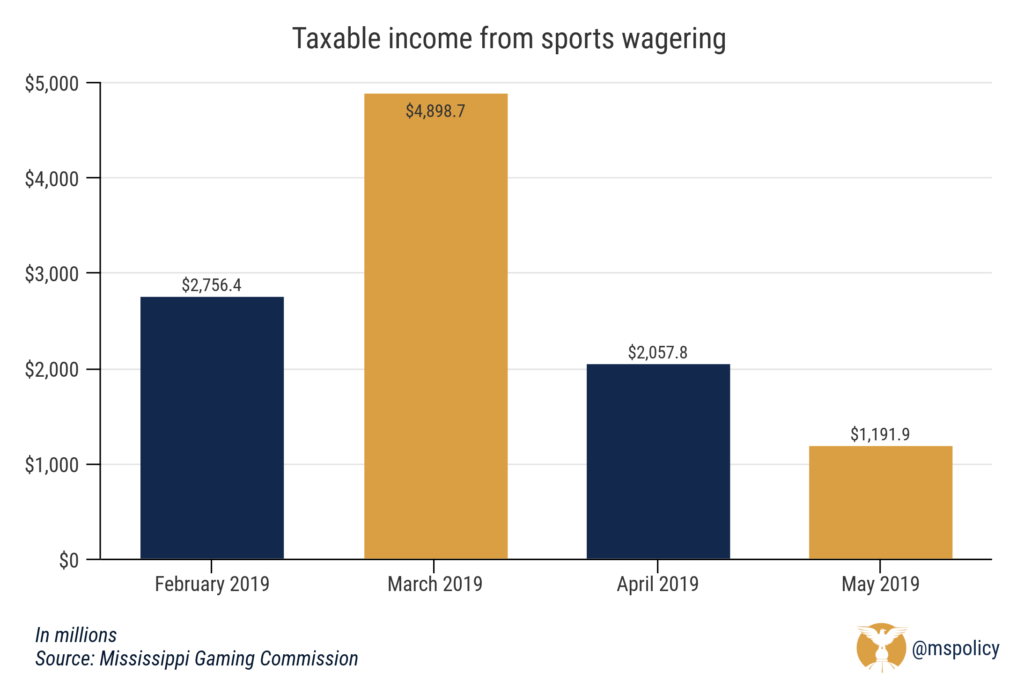

Revenue from sports betting continues to decline in Mississippi as the slow season for betting continues a couple months before football resumes.

Taxable revenue for the month of May totaled just under $1.2 million, down from around $2 million in April. In March, revenues were just under $4.9 million, a far outlier from recent trends, thanks to the college basketball tournament. January and February hovered between $2.7 and $2.8 million.

The biggest win for Mississippi’s casino-only sports betting industry, however, was Louisiana’s inability to pass their own legislation which would have legalized sports betting in Pelican State casinos and race tracks. The proposed legislation would have required local referendums in each parish, but it died on the last day of the session.

Lawmakers will not meet again until next March.

Other neighboring states

In Arkansas, sports betting became legal last week. Last November, voters approved a ballot initiative legalizing sports betting and the Oaklawn Racing Casino Resort in Hot Springs, is the first to welcome betters. While the timeline is still to be determined, a casino closer to home, Southland Gaming & Racing in West Memphis, is expected to begin collecting wagers soon. Competition has swallowed a lot of the revenue Mississippi once experienced, and this would likely add further pains to Tunica area sports betting operations.

Tennessee could also add to those pains, but they have some work to do. The state passed an online-only sports betting bill earlier this year, but it has many issues – requiring sportsbooks to buy official league data to settle in-play wagers, a very expensive entry point and high taxes, and a ban on prop bets in NCAA games. Much work remains before the Volunteer State is taking bids.

Legislation was introduced in Alabama this year, but it did not move and most consider sports betting a long-shot with our neighbors to the east.

Mississippi won’t have to repay a $570 million Community Development Block grant given to the state after Hurricane Katrina, but most of the jobs created at the Port of Gulfport were low income and employment actually shrunk at the port itself compared with pre-Katrina levels.

Gov. Phil Bryant’s office recently announced that the U.S. Department Housing and Urban Development had closed its review of the Mississippi Development Authority and jobs created at the Port of Gulfport after Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

HUD provided a $570 million Community Development Block grant to the MDA for the port for repairs and upgrades such as wharf crane rail upgrades, ship channel dredging and delivery and installation of three ship to shore rail mounted container cranes, a project that wasn’t completed until 2018.

Under the conditions of the grant, the port was supposed to maintain 1,300 jobs and add 1,300 more workers once renovations were complete in 2016, 11 years after the storm. Fifty one percent were to be made available for those with low or moderate incomes.

Of those jobs, 1,167 came from a casino hotel that leases land from the port authority. HUD allowed the MDA to count jobs added at the Island View as part of its requirements under the CDBG grant. The agency also assisted the MDA in recalculating hours worked by the employees so they could be counted as full time under the conditions of the grant.

The state said that the port had 2,085 maritime employees prior to Hurricane Katrina and that number shrank to 1,286 by 2007. A study by the Stennis Institute that was attached to the governor’s news release said that the port and its tenants directly employed 1,121 personnel and generated $425 million for the local economy.

“HUD’s $570-million investment after Hurricane Katrina was invaluable to Mississippi,” Bryant said in a news release. “I’m proud to say that we’ve met the low and moderate income national objective for CDBG funds. This would not be possible without the effort from our federal and local partners.”

The Stennis study also blamed the Great Recession from 2007 to 2009 and the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill for the downturn in economic activity for having an effect on the Port of Gulfport’s operations after Katrina.

In August 2013, HUD issued a finding on the port reconstruction that criticized the state for inadequate recordkeeping in complying with the low- and moderate-income job requirements.

A report issued in September 2013 by the Joint Legislative Committee on Performance Evaluation and Expenditure Review (PEER Committee) predicted that the port would be unable to meet its job creation requirements by the deadline.

In 2017, the MDA told HUD officials that additional jobs had been created in the expansion of the Island View Resort. HUD examined records and found that 18 percent of the 112 new hires sampled were duplicative or employees had been rehired and counted twice and 25 percent of them never worked full time.

HUD met with MDA and port officials in August 2018 to discuss progress with complying with the job creation requirements. HUD found that only 588 jobs had been created, far short of the 1,200 jobs that were supposed to be added according to the state’s plan.

MDA also used a new methodology for counting full-time jobs at Island View toward the goal, converting part-time positions using hours worked into full-time equivalent positions.

The port has added some new tenants, such as McDermott International, Sea One and Chemours, and brought back fruit company Chiquita in 2016, which relocated in 2014 to New Orleans.

Edison Chouest subsidiary Top Ship was supposed to receive $36 million in state funds to open a shipyard on property on the Industrial Canal owned by the port and employ 1,000 workers that would count toward the HUD total. The deal was scuttled in December after Top Ship wasn’t able to meet the investment or job creation requirements.

New innovations continue to make our lives easier. If only the government would get out of our way and let consumers decide for themselves.

Because of new technology, getting around town can feel incredibly easy with companies like Uber and Lyft transforming the way we get from point A to point B. Users now have a choice in what was once controlled by a government-backed monopoly.

The new option is and was largely cheaper, easier, and more convenient. Though government tried, the city of Oxford in particular, ride sharing became so popular that there was little government could do to stop it.

But while ride sharing has changed how we travel, massive progress has also been made in the field of micromobility where customers can use electric scooters and bikes to travel to their desired destinations. This has helped to solve the first-mile and last-mile gaps for many.

In the past year dozens of scooter and bike companies have sprung up to meet the needs of consumers expanding to many major and midsized communities, along with college towns.

Yet at the same time, scooters have hit some roadblocks with city governments opting to ban the service, often describing it as a nuisance. Essentially, the same treatment ridesharing services received from Mississippi governments not too long ago.

Though scooters are generally designed for urban areas, of which Mississippi has few, residents of midsized communities, particularly college towns, could stand to benefit greatly from local deregulation.

Oxford and Starkville stand out as the most logical destination for scooters.

Students would no longer have to worry about parking or missing a bus to class as scooters or electric bikes could supplement their transportation needs. While scooters have never made it to Oxford, they lasted less than a month in Starkville.

The city brought scooters in on a trial basis, while Mississippi State had a ban in place. Naturally, the confusing laws led many students, the biggest user of scooters, to bring the scooters on to campus, drawing the ire of university officials. Lime, the scooter operator, decided to leave the city as a result. And students were again left without this option.

In larger cities like Jackson or tourist towns along the Coast, the introduction of scooters could radically transform how transportation is thought about.

The dangers of scooters are not different than the dangers of any other mode of transportation. There are people who are reckless, whether it's on a scooter or behind the wheel. We can control bad behavior without punishing everyone else. The government just needs to err on the side of individual liberty and personal responsibility.