Lemonade Day 2019 is coming to the Golden Triangle. It’s a celebration that helps today’s youth become tomorrow’s entrepreneurs.

For generations, a summer tradition for boys and girls has been to make lemonade, set up a stand in front of their house or near a busy road, and earn money for that special toy they have been wanting, or maybe just to save for a future purchase. For a moment in time, children turn into entrepreneurs, even though they probably couldn’t tell you what the word means.

But lemonade stand entrepreneurs have met a force that strikes fear in the hearts of even the most seasoned professionals: the government regulator.

By now you have probably heard the stories, but they bear repeating because of the sheer lunacy of feeling the need to shut down a lemonade stand, and because they highlight the overcriminalization of our society thanks to laws we have adopted to fix every supposed issue or problem.

In California, the family a five-year-old girl received a letter from their city’s Finance Department saying that she needed a business license for her lemonade stand after a neighbor complained to the city. The girl received the letter four months after the sale, after she had already purchased a new bike with her lemonade stand money. The young girl wanted the bike to ride around her new neighborhood as her family had just moved.

In Colorado, three young boys, ages two to six, had their lemonade stand shut down by Denver police for operating without a proper permit. The boys were selling lemonade in hopes of raising money for Compassion International, an international child-advocacy ministry. But local vendors at a nearby festival didn’t like the competition and called the police to complain. When word of this interaction made news, the local Chick-Fil-A stepped up as you would expect from Chick-Fil-A. They allowed the boys to sell lemonade inside their restaurant, plus they donated 10 percent of their own lemonade profits that day to Compassion International.

In New York, the state Health Department shut down a lemonade stand run by a seven-year-old after vendors from a nearby county fair complained. Once again, they were threatened by a little boy undercutting their profits.

In response to these stories, the states of Utah and Texas have passed laws that allow children to operate occasional businesses, such as a lemonade stand, without a permit or license. Every other state, including Mississippi, should follow suit whether they have made the news or not.

As parents and as a society, we should be encouraging entrepreneurship. We should celebrate young boys and girls who want to make money, whether it’s for a new bike or to give to a ministry. When children have the right heart and the right ideas and are willing to take actions, we shouldn’t discourage it. The lessons are valuable. They learn that money comes from work, that you have to plan, and then produce a stand, signs, and lemonade. Introducing kids to the concepts of marketing, costs, customer service, and the profit motive is a good thing.

And why it has always been celebrated in our society for a long time.

Until today. But I suppose these interactions also provide these young children with another valuable but unfortunate lesson: beware of government and crony capitalism. Vendors who don’t like competition use the law to eliminate competition. And government, however good the intentions may have been, created the laws that actually work against the development of entrepreneurial values by regulating lemonade stands.

As often happens when government steps in to solve a problem, there are unintended consequences few are willing to acknowledge.

Hopefully, the absurdity of these stories has raised more than a few eyebrows. Perhaps they will cause people to recognize the downside of our regulatory burden and maybe even cause legislators to review more than a few of the laws, rules, and licensing regimes that are stifling growth, innovation, and capitalism. If we want a thriving and growing economy, we’ve got to have more entrepreneurs – including those future ones who sell lemonade in their neighborhoods today.

This column appeared in the Starkville Daily News on May 30, 2019.

New emergency telemedicine regulations are good for healthcare, they are good for competition, and they are good for consumers.

Millionaire country music stars like to pretend they spend their weekdays driving a tractor and their weekends driving pretty girls down dirt roads in their pickup truck. While they can only dream, many Mississippians live the true country life in all its glory. It is a good life, but not as simple as the performers portray it to be. Living far away from population centers can mean reduced access to many essential services, like healthcare. Maintaining access to rural emergency medicine could be the difference between life and death for many Mississippians.

In Mississippi, there are 64.4 primary care physicians for every 100,000 residents, far below the national median of 90.8. Half of the Mississippi’s rural hospitals are in financial risk. Some have closed down completely, or shuttered critical services such as emergency rooms.

Rural emergency rooms are difficult to maintain. They must stay open 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The hospital has to hire several emergency room physicians to take turns covering those shifts. If those staff physicians cannot cover a shift, the hospital has to bring in a temporary physician – often from out of state. Not only is it expensive to staff an emergency room, it can be hard to recruit multiple emergency medicine physicians to live and work in a small town. Moreover, if a rural hospital does succeed in staffing an emergency department, it will see relatively few patients. Rather than bringing additional income to the hospital, it will likely cost the hospital money to operate.

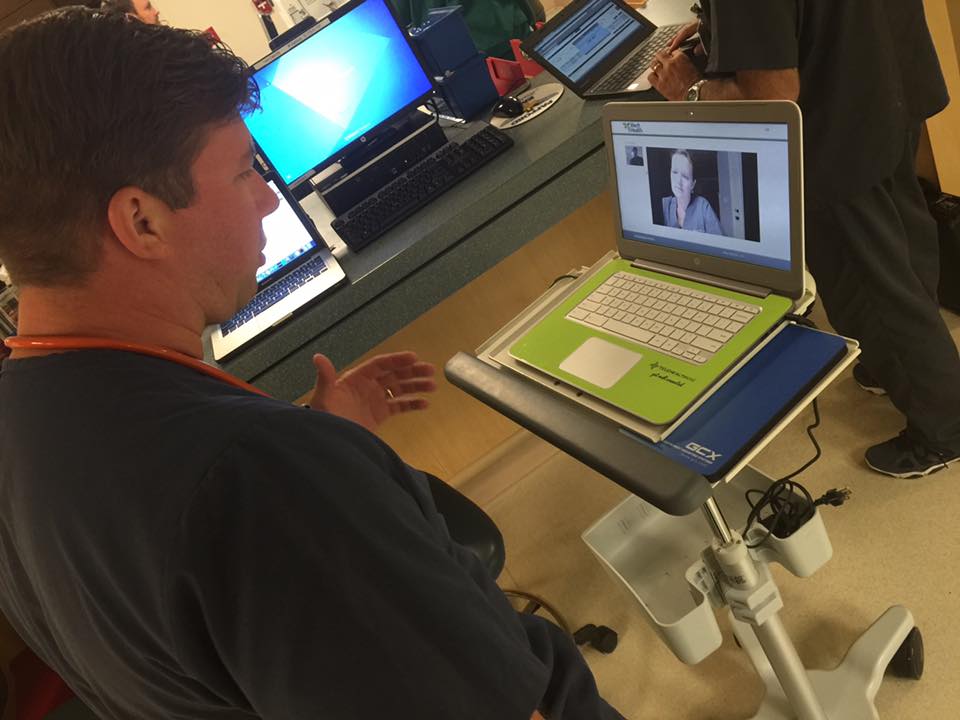

Emergency telemedicine allows some small hospitals to keep their emergency rooms open, by staffing them with physician assistants and advanced practice registered nurses. When a patient arrives, an emergency medicine physician in another location – often a larger hospital – uses audio/visual technology and remote diagnostic tools to see the patient, and to instruct the nurse or physician’s assistant on the care that is needed. Some small hospitals choose to keep a physician in the emergency room, but use emergency telemedicine to provide an additional layer of expertise and consultation for their emergency department patients.

Despite the clear benefits of emergency telemedicine, its use in Mississippi has been limited. Current regulations prohibit physicians from providing emergency telemedicine services to small hospitals unless they worked at a Level One Hospital Trauma Center with helicopter support. Mississippi only has one Level One hospital in the state, so there has been no competition for this service. However, any physician who is board certified in emergency medicine is capable of providing emergency telemedicine services, and is able to transfer a patient by helicopter, regardless of the type of hospital the physician works for.

In short, the current regulations do not make sense, and prevent new providers from offering more options for emergency telemedicine. They are also vulnerable to a legal challenge, as they likely violate the due process and equal protection guarantees of the Mississippi and U.S. constitutions, and may violate federal antitrust laws.

One telemedicine provider that has been locked out of the emergency care market is T1 Telehealth located in Canton, Mississippi. T1 Telehealth was the state’s first private telemedicine company, and it developed a new model for emergency telemedicine that it believed would provide a better service for rural hospitals and patients. But it could not offer that new model due to the regulatory restrictions.

T1 Telehealth retained the Mississippi Justice Institute – a nonprofit constitutional litigation center that I work for – to challenge the emergency telemedicine regulations. After months of input and discussions with T1 Telehealth and other stakeholders, the Mississippi State Board of Medical Licensure has taken the right approach to make the regulations fair and to increase access to healthcare. New proposed regulations have been adopted that will allow any licensed emergency medicine physician to offer emergency telemedicine services in Mississippi.

The new proposed regulations will be reviewed by the Occupational Licensing Review Commission before becoming final. Approval by the commission seems assured, as it is chaired by Gov. Phil Bryant, who has been a tireless champion of expanding telemedicine in Mississippi and a strong supporter of efforts to reform the state’s anticompetitive emergency telemedicine regulations.

The new regulations will be a great development, not just for T1 Telehealth, but for all telemedicine providers, for small rural hospitals that rely on telemedicine, and for patients across Mississippi. Competition encourages innovation, more options, better services, and lower prices. All things that will make rural healthcare and Mississippi country living that much better.

This column appeared in the Clarion Ledger on May 29, 2019.

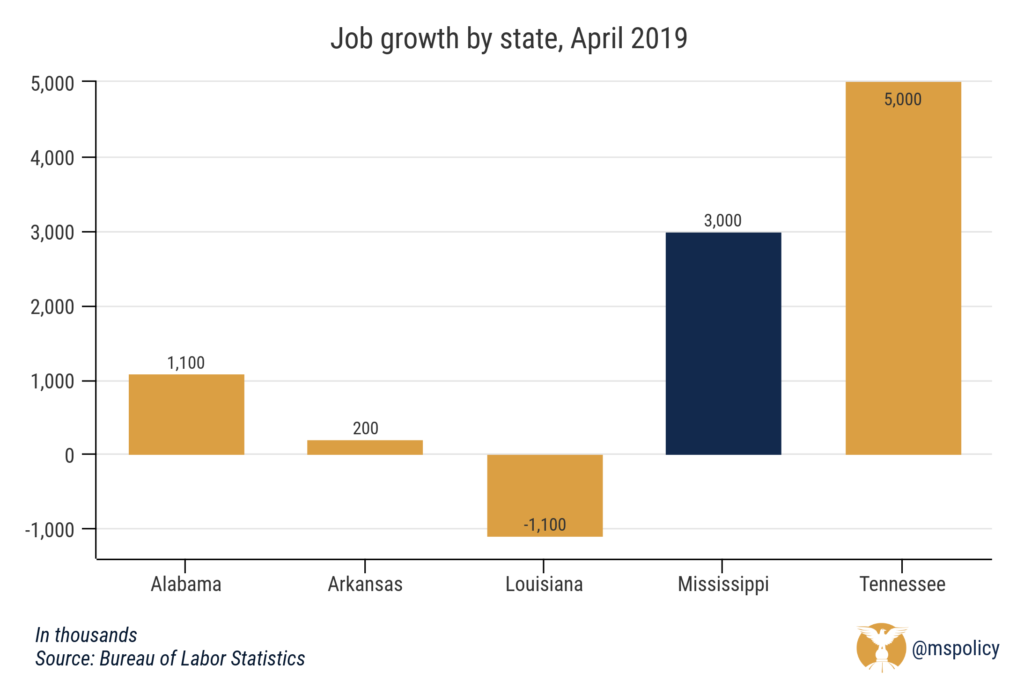

Payrolls in Mississippi jumped by 3,000 in April, erasing the slow start to the year.

The number of employees in Mississippi rose to 1,164,200, according to preliminary estimates from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. And March’s numbers were revised upward from 1,159,700 to 1,161,200.

After posting a decline in the number of jobs over the first three months of the year, Mississippi posted a solid job growth rate of .26 percent last month. And over the past year, Mississippi has added a little more than 11,000 jobs.

Only Tennessee, which added 5,000 jobs last month, had better job gains among neighboring states though there .16 percent growth rate was lower than Mississippi’s. Alabama added 1,100 jobs while Arkansas added 200 jobs. Louisiana lost 1,100 jobs last month.

Construction (+300), manufacturing (+1,000), trade, transportation, and utilities (+1,500), financial activities (+200), education and health services (+100), leisure and hospitality (+100), and government (+600) all added jobs last month. Professional and business services (-600) was the only sector to see job losses last month.

Encouraging numbers, but problems exist

While this is good news on the whole, particularly as it compares to our neighbors, and we should celebrate job growth, there are two areas of concern that should be noted.

We added 600 jobs through government. When our population and in-migration rates stay flat (or decrease) but our government jobs increase, that’s a sign of a dependence on government for economic growth. That’s not a good free-market policy and usually indicates a lack of reliance of the private sector. Mississippi already produces approximately 56% of its economic output from the public sector, putting it fourth worst in the nation for reliance on government.

Professional and Business Services dropped by 600 jobs. This is not a trend we hope to see continue. To grow our economy from the private sector, we need more entrepreneurs, start-ups, and professionals. These jobs tend to focus on creativity and serving customers in innovative ways that create meaningful and long-lasting value. Such businesses also can create more jobs, more companies, and even generate significant wealth for founders, who often turn around and invest in new companies or donate generously through charitable giving and philanthropy.

We applaud the improved job growth numbers, but we want to see improvements in these two areas so that our economy can generate more sustainable, long-term growth.

With the statewide political campaigns gearing up, we are sure to hear often this year from candidates who say they want to stop government overreach from stifling small businesses, innovative startup companies, and job creation in Mississippi. This is a worthy goal.

But some may wonder, exactly what does this kind of government overreach look like? Where do we draw the line between the proper role of government and unnecessary government interference?

To find the answer, we need only look to the travails of an innovative technology startup out of Madison named Vizaline. Two Mississippi businessmen put their experience and ideas together to offer something new. Brent Melton had worked in community banks for 42 years and knew they needed a way to understand the boundary lines of smaller properties they financed. For these smaller loans, surveys were neither required nor financially feasible. Scott Dow had spent two decades working with geospatial remote sensing and 3D computer modeling and he knew how to make this idea a reality.

Together, they created software that could take a properties’ publicly available legal description – which is just cryptic words on paper generated by professionally licensed surveyors – and turn it into something anyone can understand: a drawing of the described property lines on a map.

Vizaline does not conduct surveys. It does not hold itself out as a professional surveyor. It simply takes information already generated by surveyors and puts it into a more user-friendly format. Vizaline only sells its services to small community banks who need and want a more cost-effective and user-friendly way to understand the properties they are financing. These are sophisticated customers. They know exactly what they are getting. And they want it. Nobody is getting duped.

Nevertheless, the government decided it needed to stop these transactions between a willing seller and willing, satisfied customers. The Mississippi Board of Licensure for Professional Engineers and Surveyors sued Vizaline. The government board claimed Vizaline was engaged in “unlicensed surveying.” It asked the court to shut down Vizaline, and to force them to hand over all the money they have ever earned.

Vizaline fought back. It obtained legal representation from the Institute for Justice and filed its own lawsuit, arguing that the government’s actions were unconstitutional. Everyone in America has the right to free speech, including the right to take existing, publicly available information, and create a new representation of that same information. Moreover, the government board – which is composed entirely of licensed surveyors and engineers – is not trying to protect the public. It is trying to protect its own industry from competition. Unfortunately, for the board, that is not a constitutionally valid function of government.

While Vizaline’s lawsuit was still ongoing, the Mississippi legislature had an opportunity to stop this government overreach. A bill introduced last session would have clarified that the Mississippi Board of Licensure for Professional Engineers and Surveyors does not have the authority to stop companies like Vizaline from doing business in our state. The legislature missed that opportunity, which is disappointing, given how many of our elected officials campaigned on stopping exactly this type of government overreach.

Vizaline is currently appealing its case in federal court. The Mississippi Justice Institute joined the Cato Institute and the Pelican Institute to file a legal brief supporting Vizaline’s case, and urging the court to uphold all Mississippians’ right to disseminate public information, and to do business free from unnecessary government interference.

So where is the line between proper exercises of government power and government overreach? While the government tries to stop it from drawing lines on paper, Vizaline has drawn a new line in the sand against government overreach. Broadly enforcing vague laws simply to protect industry insiders from competition with new, innovative competitors is not a valid function of government. The Mississippi Justice Institute is proud to stand with Vizaline, and would be proud to stand with any Mississippian facing similar government overreach.

This column appeared in the Meridian Star on May 17, 2019.

When Rachel Sugg first heard about Airbnb doing well in Jackson, she was skeptical.

She, like many others, associated Airbnb with young people and vacation destinations. However, since she and her husband incorporated Airbnb into their real estate business two years ago along with their long-term rentals, her view of who Airbnb serves has changed.

The Sugg’s placed their first short term rental unit on Airbnb in April of 2017. From then on, it had been booked, and kept booked.

Two years, three units and 500 people later, Airbnb has turned out to be more profitable for the Suggs then their numerous long-term rentals. And Rachel’s view of Airbnb’s main consumer is different than before.

The majority of those staying in the Sugg’s locations, Rachel has noticed, have turned out to be working class, blue-color individuals, who are, for the most part, coming to Jackson for work related reasons, or college students and their parents.

Rachel believes that an important draw to Airbnb is not only the price, but the fact that visitors can have a one-on-one experience with their host. With Airbnb, there is always someone local to call who is familiar enough with the area to give an expert recommendation. Having someone so close at hand to act as a personal ambassador to Jackson, changes the whole experience of coming here, into something personal.

Not only does the personal experience Airbnb hosts provide change negative views of Jackson, but it brings people to the city as well. In her experience, Rachel has had guests change their stays from one night in Jackson, to two days, or more after having a great experience that first evening. Or, in some cases, people who have come to the area for an appointment in Madison have stayed in Jackson at one of the Sugg’s three Airbnbs, because they there was no Airbnb available in Madison.

Airbnb travelers generally have a different idea of traveling than others might, even if they are traveling for work. Rachel says they tend to be more laid back. They want to get a real feel for the area, not just the touristy version. They want to experience the culture. They want to get to know where they are, not just travel through, staying one night at a hotel then leaving the next morning.

Rachel has found that the benefits Airbnb provides to the Jackson community are numerous; it draws people in, changes minds about Jackson and Mississippi, incentivizes the upkeep of property, brings money into Jackson and the surrounding area, and not only exposes visitors to Jackson but exposes Jackson residents and their neighbors to completely new people.

It is an experience. And, according to Rachel, it’s good for Jackson.

According to a recent study, it would take more than 13 weeks to wade through the 9.3 million words and 117,558 restrictions in Mississippi’s regulatory code. Yet we know little about many of those regulations, such as if they are even necessary today.

The Mercatus Center at George Mason University’s James Broughel and Jonathan Nelson wrote a policy snapshot of Mississippi’s regulatory state as part of a national project to analyze regulatory burdens nationwide.

These regulations can impose huge costs as businesses are forced to comply with them and can also become anticompetitive devices, since many of them are written by the industries that are being regulated.

Mississippi is roughly mid-pack in the amount of its regulatory framework. But the one consistent among most states is that the number of regulations are only increasing.

That changed in a big way in one state.

Idaho has a somewhat unique regulatory process. Each year, the state’s regulatory code expires unless reauthorized by the legislature. While this does provide a check that is missing in places like Mississippi, it is normally a formality. But not this year.

Now, Idaho Gov. Brad Little is tasked with implementing an emergency regulation on any rule he would like to keep. The legislature will consider them next year. And there are certainly needed regulations, just as there are unnecessary or outdated regulations that serve little purpose.

But, as Broughel has pointed out, the burden on regulations now switches from the governor or legislature needing to justify why a regulation should to be removed to justifying why we need to keep a regulation.

To reduce red tape, Mississippi could move toward a sunset provision similar to Idaho or introduce a regulatory cap that orders the removal of two old rules each time a new one is added. A thriving economy is one with fewer regulations, a lighter government touch, and more freedom for small and mid-sized businesses.

If a regulation is so important, prove it.

Unnecessary and burdensome regulations make it harder for Mississippians to earn a living.

According to a new report from Pete Blair with Harvard University and Bobby Chung with Clemson University, occupational licensing reduces labor supply by an average of 17-27 percent. An earlier report from the Institute for Justice found that Mississippi has lost 13,000 jobs because of licensing requirements.

While licensing was once limited to areas that most believe deserve licensing, such as medical professionals, lawyers, and teachers, this practice has greatly expanded over the past five decades.

Today, approximately 19 percent of Mississippians need a license to work. This includes everything from a shampooer, who must receive 1,500 clock hours of education, to a fire alarm installer, who must pay over $1,000 in fees. All totaled, there are 66 low-to-middle income occupations that are licensed in Mississippi.

The new report also looks at the varying requirements for occupational licensure, including prohibitions on those with criminal convictions, whether the conviction had anything to do with the occupation or not.

This year, the legislature passed a new law that prohibits occupational licensing boards from using bureaucratic rules to prevent ex-offenders from working. The law requires occupational licensing boards to eliminate blanket bans and “good character” clauses used to block qualified and rehabilitated individuals from working in their chosen profession.

Under the Fresh Start Act, licensing boards must adopt a “clear and convincing standard of proof” in determining whether a criminal conviction is cause to deny a license. This includes the nature and seriousness of the crime, the passage of time since the conviction, the relationship of the crime to the responsibilities of the position, and evidence of rehabilitation. The law also creates a preapproval process that allows ex-offenders to determine if they may obtain a particular license before undertaking the time and expense of training, education and testing. In addition, the law protects licensed individuals who fall behind on their student loans from losing their occupational license.

All too often, occupational licenses only serve to protect certain industries, rather than protecting public health or wellbeing. We should continue to look for ways to help people find gainful employment rather than implementing unnecessary roadblocks. Working provides purpose and the opportunity for families to flourish. We should do everything possible to encourage it.

T1 Telehealth is a Mississippi company that provides innovative telemedicine services, but has been limited in the healthcare it can deliver because of government regulations that hampered competition.

The Mississippi Justice Institute has been representing T1 Telehealth in its efforts to challenge these regulations. On May 9, 2019, after months of negotiations, the Mississippi State Board of Medical Licensure adopted a new proposed rule that will expand telemedicine services in the state by allowing additional providers to offer telemedicine in the emergency room.

“The new regulations will be a great development, not just for T1 Telehealth, but for all telemedicine providers, for small rural hospitals that rely on telemedicine, and for patients across Mississippi,” said Aaron Rice, the Director of the Mississippi Justice Institute. “The Mississippi Board of Medical Licensure took the right approach to make the regulations fair and to increase access to healthcare in Mississippi.”

In Mississippi, there are 64.4 primary care physicians for every 100,000 residents, far below the national median of 90.8. Many rural hospitals struggle to fund and staff their emergency departments, which require multiple emergency room physicians to take turns covering shifts to ensure 24/7 access. Emergency telemedicine allows these small hospitals to keep their emergency rooms open, by staffing them with physician assistants and advanced practice registered nurses. When a patient arrives, an emergency medicine physician in another location uses audio/visual technology and other tools to see the patient, and to instruct the nurse or physician’s assistant on the care that is needed.

The old regulation prohibited physicians from providing emergency room telemedicine services to small hospitals unless they worked at a Level One Hospital Trauma Center with helicopter support. Mississippi only has one Level One hospital in the state, so there was no competition for this service. However, any physician who is board certified in emergency medicine is capable of providing emergency telemedicine services, and is able to transfer a patient by helicopter, regardless of the type of hospital the physician works for. The old regulation locked out companies like T1 Telehealth, which was the first private telehealth company in the state, even though the company saw a need and believed it could provide better emergency telemedicine services. The new regulation will now allow new companies to compete.

“The thing that Americans like better than anything is choice,” said Todd Barrett, CEO of T1 Telehealth. “People want to have the opportunity to say I don’t like that, but there’s this other option I can try and two competitors in a market understand that. They both strive to be the one people are going to call. That makes everything better and cheaper by helping to keep costs down and improve quality. There are two ways to differentiate ourselves and that’s either price or quality. This new regulation allows us to come in and prove ourselves, show how much better it is, what the results are, and how patients benefit.”

For Barrett, innovating in healthcare is all he has ever done. It is what he knows. Since graduating from Pharmacy School in 1988, he has started and sold three pharmacy companies and a technology company, each time sensing and filling a need.

“Can we create something that allows more patients to be treated and made better with less dollars and if it looks like that we’re interested in seeing how we can fit in and make that happen,” Barrett added.

The new proposed regulation will be filed with the Secretary of State to allow time for public comments. It will also be reviewed by the Occupational Licensing Review Commission before becoming final. Once the regulation is finalized, many expect to see a new, vibrant market emerge in the provision of emergency telemedicine services.

A new federal grant program and an emerging technology could be the tools used by the state’s non-profit electric power associations to get high-speed internet to their customers.

On April 12, Federal Communications Commission Chairman Ajit Pai announced a proposal to award $20.4 billion over the next decade toward rural broadband networks in a program called the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund.

This would be repurposed money from the FCC’s Universal Service Fund which already provides money for extending rural broadband service in addition to low-income phone service and low-coast broadband access for schools and libraries.

Thanks to a change in state law, EPAs in mostly-rural Mississippi are well placed to enter the reverse auctions to receive grants from the new federal program. A reverse auction differs from a conventional one since it has one buyer and many potential sellers.

It would increase Mississippi’s reliance on federal funds.

The Mississippi Broadband Enabling Act was signed into law by Gov. Phil Bryant, went into effect immediately and it allows the state’s 26 EPAs, also known as cooperatives, to provide broadband to their primarily rural customer base.

The new law requires EPAs to conduct economic feasibility studies before providing broadband services, maintain the reliability of their electric service, maintain the same pole attachment fees for an EPA-owned broadband affiliate as for private entities wishing to use the EPA’s infrastructure and submit a publicly-available compliance audit annually.

According to data from the latest FCC wireless competition report, there is a digital divide in Mississippi. Ninety-five percent of urban residents in Mississippi have access to high-speed internet service (defined as 25 megabits per second). In rural areas, only half of residents have access to that level of internet service. In 12 of the state’s 82 counties, five percent of the population or less has access to high-speed internet.

In 27 counties, only 25 percent or less of the population has high-speed internet service available.

The technology that might bridge the divide in Mississippi and in other rural states could be 5G (fifth generation) wireless. Signals in 5G operate on three different spectrum bands that include:

- Low band — 600 megahertz, 800 megahertz and 900 megahertz.

- Mid band — Frequency bands of 2.5 gigahertz, 3.5 gigahertz and 3.7 gigahertz to 4.2 gigahertz.

- High band — 28 gigahertz, 24 gigahertz, 37 gigahertz, 39 gigahertz and 47 gigahertz (millimeter wave or high band).

5G can also be supported on unused parts of the spectrum below 4 gigahertz, which is the frequency range used by present 4G LTE coverage.

Right now, the FCC has already started auctioning bandwidths in the low band. A recent report by the watchdog group Citizens Against Government Waste recommends that FCC also conduct spectrum auctions with strong oversight for mid band, with the proceeds going to taxpayers.

According to the report, since 1994, the FCC has conducted 101 spectrum auctions that have generated $121,672,180,000 for taxpayers with the awards of 44,499 licenses. The report also says the mid band auction could generate an additional $11 billion to $60 billion for taxpayers, depending on how much of the spectrum is put on the market.

5G will be much faster, capable in urban areas of speeds of 100 gigabits per second for the high band, which is 100 times faster than 4G. Also, 5G has the advantage of low latency, which is the time that passes between when information is received and when it can be used by the device on the network. This means it could be used to replace conventional WiFi.

Since 5G uses shorter wavelengths, the antennas can be much smaller, which means a tower can support more antennas. This allows 1,000 more devices per meter than what’s supported by the existing 4G network.

The problem with high band is these wavelength have a much shorter effective range. They require a clear line of sight between the mobile device and the antenna. These signals can easily be blocked by solid objects, rain and even humidity, which would be a problem in sweltering Mississippi summers.

Also, 5G download speeds in rural areas would be only fractionally as quick as those in urban areas with large numbers of antennas, which would be supported by trunk lines made of fiber-optic cable.

These issues would provide complications for using 5G as the means to extend high-speed internet service to rural areas of Mississippi.

The marketplace is already working on solutions.

AT&T has been testing a way to use power lines (Project AirGig) to deliver 5G service. The technology has already been successfully tested in Georgia and internationally. The company says it could be used to bring high-speed internet to customers in suburban and rural neighborhoods.