Mississippi has among the most limiting cottage food laws in the country.

Passed just a few years ago, Mississippi’s cottage food operators law allows those who bake or prepare goods at home to sell them to the public without a government inspection or certificate. Because of this law, those who had long been baking without asking government now had permission from the state.

But the law limits gross annual sales to less than $20,000. This is the third lowest sales cap in the county, according to a report from the Institute for Justice.

Among states that have cottage food laws, only South Carolina ($15,000) and Minnesota ($18,000) have lower caps. Seven other states have a similar $20,000 cap, including Alabama and Louisiana.

Our two other neighboring states, Arkansas and Tennessee, however, have no cap. They are two of 28 states that do not place a limitation on what you can earn.

Cottage food limitations by state

| State | Sales cap | Online sales | Restaurant/ retail sales |

| Alabama | $20,000 | No | No |

| Arkansas | None | No | No |

| Louisiana | $20,000 | No | Yes |

| Mississippi | $20,000 | No | No |

| Tennessee | None | No | No |

Among states that have a sales cap, the average is just under $29,000.

Who are cottage food operators?

According to the IJ report, 83 percent of cottage food producers are female while more than half (55 percent) live in rural communities.

Just a few (20 percent) consider this there main occupation. Forty-two percent say it is a supplementary occupation and 35 percent categorize it as a hobby. And the most significant benefit for most operators was the ability to be your own boss and have flexibility and control over the schedule. Indeed, the ability to balance work and family was a top consideration for female business operators, along with the low operational costs.

This year legislation would have lifted the cap to $35,000. While there shouldn’t be a cap, that would have been an improvement. It passed the House, but failed to make it out of the Senate.

While most cottage food operators are micro-enterprises, some do or would like to grow into sizeable operations. And we should support that.

After all, that should be the goal of the state, to encourage growth. Cottage food businesses enhance the financial and personal well-being of their owners. They provide an in-demand product to a willing consumer. And they positively benefit sales tax collections for the state.

There has not been evidence to suggest that lightly regulated states pose a threat to public health as some like to indicate. The limitations really just serve to limit competition for established businesses. By eliminating restrictions in Mississippi, we can give consumers new options, grow the economy, and encourage entrepreneurship.

Mississippi’s economic growth lagged behind most of its neighbors in 2018 even though the state’s economy had its best year since 2008.

The report by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, which is part of the U.S. Department of Commerce, estimated the state’s real gross domestic product grew at a rate of one percent in 2018, a big improvement from 2014, when BEA estimated the state’s GDP shrunk by 1.2 percent.

Since then, the numbers have been small, but steadily improving, with 0.4 percent growth in 2015, 0.3 percent in 2016 and 0.5 percent in 2017.

| Year | GDP growth |

| 2014 | -1.2% |

| 2015 | 0.4% |

| 2016 | 0.3% |

| 2017 | 0.5% |

| 2018 | 1.0% |

Real domestic product is defined as the market value of goods and services produced by the labor and property located in a state.

That ranked the state 42nd nationally, with Alaska in last place with a GDP that shrunk by 0.3 percent. Delaware and Wyoming (0.3 percent) were next worst. Alaska was the only state whose GDP contracted in 2018.

The southeast — which includes Mississippi’s neighboring states plus Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia and West Virginia — averaged 2.6 percent of GDP growth.

In the region, Mississippi was ahead of only Arkansas (0.9 percent GDP growth) and was edged slightly by Louisiana (1.1 percent).

The best growth rates regionally were Florida (3.5 percent) and Tennessee (3 percent). Washington’s economy grew at a rate of 5.7 percent, best in the nation, followed by Utah (4.3 percent), Idaho (4.1 percent) and Arizona (4 percent).

The biggest sectors contributing to Mississippi’s economic improvement were wholesale trade (0.17 percent), retail trade (0.16 percent), hunting and fishing (0.13 percent) and 0.10 percent growth for both durable and non-durable goods manufacturing.

According to the report, wholesale trade increased 9.1 percent nationally and contributed to growth in all 50 states.

In 2018, Mississippi missed the boat on information services, which the BEA says increased 8.9 percent nationally. The industry’s share of the state’s gross domestic product contracted by 0.02 percent.

Finance and insurance was the biggest downward mover in 2018, shrinking its share of Mississippi’s GDP at a rate of 0.18 percent. Construction’s share of GDP withered at a rate of 0.04 percent.

Poor fourth quarter numbers dragged Mississippi downward, according to the BEA estimate.

In the fourth quarter of 2018, Mississippi’s GDP growth was least amongst its neighbors at 0.5 percent and ranked 47th, outpaced by Alabama (2.1 percent), Arkansas (1.5 percent), Louisiana (1.3 percent) and Tennessee (1.6 percent).

Texas, which had its GDP grow at a rate of 3.3 percent in 2018, recorded the nation’s best growth in the fourth quarter of 2018 with 6.6 percent.

More than five years after political dignitaries broke ground in the Biloxi dirt at the corner of Highway 90 and Interstate 110, minor league baseball is not working out quite as well in the Gulf Coast town as some had hoped. Or had been sold by consultants.

In 2013, the city of Biloxi conducted a feasibility study that predicted the stadium would draw 280,000 fans annually, or a little more than 4,000 per game.

The study, a common exercise in such municipal financing plans, provided city leaders with what they needed to move forward. The city borrowed $21 million to help build the stadium. Unfortunately, for the city – and taxpayers – the hopeful projections of that $25,000 study have not panned out.

The Shuckers have never drawn more than 180,000 fans in a year, and last year they were down to just over 160,000 in attendance.

As a result of the lower than predicted numbers, the city is forced to reach into its general fund for about half of the $1.2 million they owe each year on the debt. Many leaders hold out hope that if more development comes to the area, it will increase attendance and revenue.

In another minor league town in Mississippi, there is plenty of development around Trustmark Park in Pearl. An outlet mall, funded in part by the state’s Cultural Retail Attractions Program, Bass Pro Shop, Sam’s Club, and a Holiday Inn all surround the park on land that was mostly swamps not so long ago.

Still, the Mississippi Braves, who play in the Southern League with the Shuckers, drew just over 150,000 last year fans last year. This is down considerably from the 190,000 they averaged in 2016 and 2017, and from 2013 through 2015 when their attendance was over 200,000 each year.

What has this meant for Pearl? The money from this new revenue stream hasn't been enough to cover the debt on the shopping center and ballpark complex. In 2013, the city paid $967,944 to cover the shortfall, though that amount has declined in recent years, shrinking from $911,748 in 2014 to payments of $589,902 in 2015 and 2016 and $619,048 in 2017, the last year records were available.

The city also has to pay $651,852 annually until 2024 to cover a $4,433,165 agreement with the site developers. These outlays are covering underpayments from 2011, 2012 and 2013 on sales tax diversions from the Mississippi Department of Revenue that the city didn't give to the developer.

The Braves have turned the game of pitting city against city into an art form. They moved their Single-A franchise from Macon, Georgia to Rome, Georgia after securing $15 million to build a new stadium. They received $28 million from Pearl when the Double-A team moved from Greenville, South Carolina. And they were able to secure $64 million from Gwinnett county, Georgia when they moved the Triple-A franchise from Richmond, Virginia.

But their biggest win, if you will, was in Cobb County, Georgia. The Braves were able to receive $722 million from the county to move the big league team just north of the city in 2017.

It’s hard to blame the Braves, or any team that receives taxpayer subsidies. Their owner, Liberty Media, is doing what any good owner does; negotiating the best deal for its company and shareholders. And the attraction for mid-sized cities to have a minor league ballpark is understandable. We buy into the glitz or maybe the community pride that comes with having a professional franchise in your hometown. It gives local politicians something to highlight as everyone is convinced that minor league baseball is good for tourism and no matter what the taxpayer cost, the community is better off. Yet, we have mounds of economic data that tell us that simply isn’t true.

As the years pass and as more become aware of just how big of a raw deal sports subsides – minor league or professional – often are for cities, perhaps more local officials will choose not to give in to the economic development game. Or maybe local communities will rise up.

As for Biloxi and Pearl, the best they can do is hope the numbers turn around…and that the Braves and the Brewers don’t go looking for a new ballpark when their leases run out.

This column appeared in the Madison County Journal on May 1, 2019.

The month of May is here. It is getting warmer and summer will be upon us soon. But be warned, you may also see an unregulated, unlicensed lemonade stand along the side of the road.

For generations, a summer tradition for boys and girls has been to make lemonade, set up a stand in front of their house or near a busy road, and earn money for that special toy they have been wanting, or maybe just to save for a future purchase. For a moment in time, children turn into entrepreneurs, even though they probably couldn’t tell you what the word means.

But lemonade stand entrepreneurs have met a force that strikes fear in the hearts of even the most seasoned professionals: the government regulator.

By now you have probably heard the stories, but they bear repeating because of the sheer lunacy of feeling the need to shut down a lemonade stand, and because they highlight the overcriminalization of our society thanks to laws we have adopted to fix every supposed issue or problem.

In California, the family a five-year-old girl received a letter from their city’s Finance Department saying that she needed a business license for her lemonade stand after a neighbor complained to the city. The girl received the letter four months after the sale, after she had already purchased a new bike with her lemonade stand money. The young girl wanted the bike to ride around her new neighborhood as her family had just moved.

In Colorado, three young boys, ages two to six, had their lemonade stand shut down by Denver police for operating without a proper permit. The boys were selling lemonade in hopes of raising money for Compassion International, an international child-advocacy ministry. But local vendors at a nearby festival didn’t like the competition and called the police to complain. When word of this interaction made news, the local Chick-Fil-A stepped up as you would expect from Chick-Fil-A. They allowed the boys to sell lemonade inside their restaurant, plus they donated 10 percent of their own lemonade profits that day to Compassion International.

In New York, the state Health Department shut down a lemonade stand run by a seven-year-old after vendors from a nearby county fair complained. Once again, they were threatened by a little boy undercutting their profits. A state senator in New York has since filed legislation to legalize lemonade stands. That is correct, we need new laws to clarify that a seven-year-old can run a lemonade stand with the government’s blessing.

For those who may read this and believe the world has gone crazy, we do have a story in Missouri that ended on a good note – though there is plenty of crazy in this story. An eight-year-old boy was being heckled by neighbors inquiring about his permit. If those potential customers got sick, they wanted to know “who we should go to.” The neighbors then proceeded to yell at the boy’s mom after the boy went inside. Fortunately for the boy, the local police department heard about the incident and came by the boy’s lemonade stand to show their support, and to provide their stamp of approval.

As parents and as a society, we should be encouraging entrepreneurship. We should celebrate young boys and girls who want to make money, whether it’s for a new bike or to give to a ministry. When children have the right heart and the right ideas and are willing to take actions, we shouldn’t discourage it. The lessons are valuable. They learn that money comes from work, that you have to plan, and then produce a stand, signs, and lemonade. Introducing kids to the concepts of marketing, costs, customer service, and the profit motive is a good thing.

And why it has always been celebrated in our society for a long time.

Until today. But I suppose these interactions also provide these young children with another valuable but unfortunate lesson: beware of government and crony capitalism. Vendors who don’t like competition use the law to eliminate competition. And government, however good the intentions may have been, created the laws that actually work against the development of entrepreneurial values by regulating lemonade stands.

As often happens when government steps in to solve a problem, there are unintended consequences few are willing to acknowledge.

Hopefully, the absurdity of these stories has raised more than a few eyebrows. Perhaps they will cause people to recognize the downside of our regulatory burden and maybe even cause legislators to review more than a few of the laws, rules, and licensing regimes that are stifling growth, innovation, and capitalism. If we want a thriving and growing economy, we’ve got to have more entrepreneurs – including those future ones who sell lemonade in their neighborhoods today.

Hinds county, home to Mississippi’s capital city, saw its population decrease by nearly 3,000 residents last year.

According to new data of population estimates from July 1, 2017 through June 30, 2018 released by the U.S. Census Bureau, Hinds county is down to 237,085 residents. The county’s population was 240,033 last year. This marks the sixth consecutive year of a population decrease in Hinds county after a small gain to 248,643 in 2012. The population is down 3.5 percent during that time.

Hinds county’s population decline was in line with the state’s population decrease of 3,133 during the same time period.

For the second straight year, Desoto county had the largest growth, in terms of number and percentage. The Memphis suburb added 3,087 residents last year for a growth of 1.7 percent. Lamar, George, Lafayette, and Madison counties round out the top five for percentage growth over the past year. They were the only counties to grow by 1 percent or more.

| County | Population growth | Percentage growth |

| Desoto | 3,087 | 1.7% |

| Lamar | 1,021 | 1.7% |

| George | 277 | 1.2% |

| Lafayette | 556 | 1% |

| Madison | 998 | 1% |

Harrison county had the second largest gain in terms of population growth, adding 1,717 residents (or 0.8 percent) last year.

Hancock, Jackson, Pontotoc, Rankin, Stone, and Union counties all posted gains of at least 0.5 percent. No one else did.

Fifty-seven of the state’s 82 counties saw population decreases last year. The biggest losers, in terms of percentage, were Quitman, Washington, Issaquena, Coahoma, and Carroll counties.

| County | Population growth | Percentage growth |

| Quitman | -185 | -2.6% |

| Washington | -1,139 | -2.5% |

| Issaquena | -33 | -2.5% |

| Coahoma | -557 | -2.4% |

| Carroll | -206 | -2% |

Outside of small pockets in the Jackson metro area, on the Coast, near Tupelo, and the Memphis suburbs, population is stagnant at best.

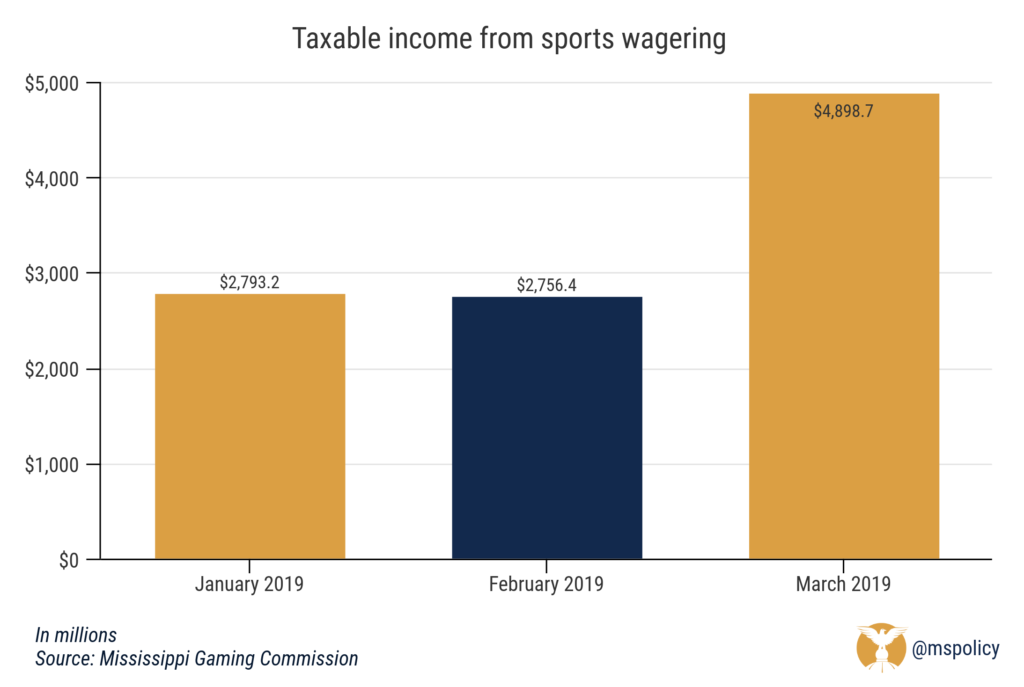

The NCAA Tournament provided a big boost to Mississippi casinos in March as revenues from sports gambling nearly doubled February during an otherwise quiet time of the year.

In March, total taxable revenue was $4.9 million versus $2.8 million in February.

But while Mississippi was the first state in the Southeastern Conference blueprint to have legalized sports gambling after the Supreme Court overturned the federal ban, more players are entering the field and making it easier to wager on sports.

To place a bet on sports in Mississippi, you have to do it at a casino. That may be attractive for a destination event such as the Super Bowl or a major boxing match, but it’s likely not going to happen for an average basketball or baseball wager on a Tuesday night. That person will continue to use an illegal, offshore website, which costs the state revenue it would otherwise receive.

Meanwhile to the north, Tennessee is on the cusp of legalizing online sports gambling. While the Volunteer State does not have casinos, those interested in betting on a sporting event will be able to do so from their smartphone or computer. Obviously making it much easier, and more convenient to place a bet.

This would likely have the biggest impact on the already declining revenue of Tunica casinos. Another casino is closing this summer, leaving the county with just six remaining casinos, a far cry from the boom of the 1990s when those six were the only casino destinations for hundreds of miles. Gaming payrolls peaked at 13,000 in Tunica in 2001, but they are down to less than 5,000 today.

Today, it’s much easier to find a casino near your house, including one in West Memphis, Arkansas.

So while the Mississippi legislature had the vision to approve sports gambling when it was still illegal, pending the Supreme Court decision that gave authority back to the states, the limitations on where the consumer can bet will likely hurt the state as sports gambling becomes more common place across the country.

Gov. Phil Bryant has changed his mind on film incentives after signing into law earlier this month a bill that brought back some subsidies that expired in 2017.

Senate Bill 2603 allows Mississippi-based motion picture production companies to receive up to $5 million for payroll and fringe benefits paid to out of state, non-resident employees. The bill, as originally written, would’ve provided to out-of-state production companies up to $10 million for payroll and fringe benefits for out of state employees.

This was reduced in conference to $5 million and restricted to production companies that have been certified by the Mississippi Development Authority to have filed income taxes in the state in the past three years and filmed at least two motion pictures in the state in the past 10 years.

The law went into effect immediately and there isn’t a repealer, which means there’s no expiration date on the incentives.

The bill signing marked a major shift in Bryant’s opinion on the motion picture production subsidies, which are being curtailed or eliminated in several other states.

The governor urged the legislature in his FY2018 budget recommendation to allow the Motion Picture Incentive Rebate Program to expire, citing a 2015 report by the Joint Legislative Committee on Performance Evaluation and Expenditure (PEER) as one of the reasons.

“While I support the jobs and attention that films bring to Mississippi, taxpayers should no longer subsidize the motion picture industry at a loss,” Bryant said in his budget recommendation. “The motion picture incentive rebate has cost approximately $25 million since 2011.

“Allowing the motion picture incentive rebate to expire could save a similar amount over the next five years.”

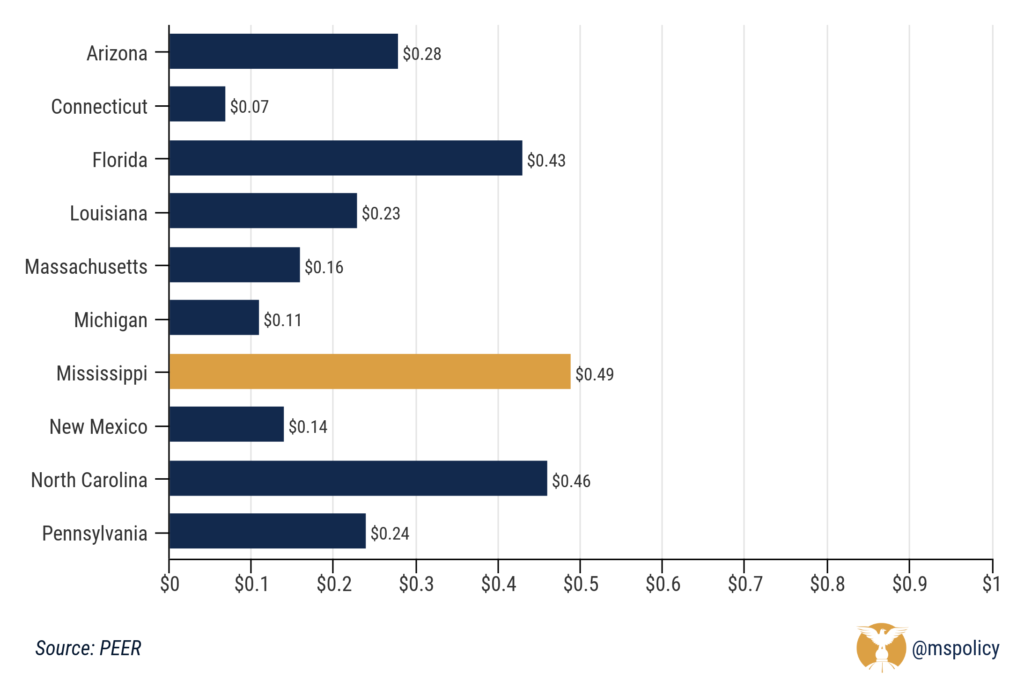

The study showed that the state lost 51 cents on every dollar invested in the program since the program’s enactment in 2004.

Since 2009, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 13 states have ended their incentive programs.

There’s plenty of evidence that’s pointing policymakers toward eliminating these subsidies. Indeed, Mississippi’s failure to make a profit on film incentives isn’t surprising. Nor is it out of the ordinary. It’s in line with every other report on incentives, as shown in the graphic below. Film production companies win and taxpayers lose.

A 2016 study by Michael Thom — an assistant professor at the University of Southern California Price School of Public Policy — found that motion picture incentive programs had little to no effect on the economies of the states with the incentives.

Sales and lodging tax waivers had no effect on four different economic indicators, while transferable tax credits — such as the ones in Louisiana — had a small, sustained effect on industry employment levels but no effect on wages.

Refundable tax credits had no employment effect and only a temporary effect on wages.

Mississippi has cash rebate program on eligible expenditures and payroll and provides sales and use tax reductions on eligible purchases and rentals. Rebates are capped at $10 million and the annual rebates provided are capped at $20 million. At least 20 percent of production crew of an eligible production must be Mississippi residents.

Did you know that Mississippi has a law on the books that allows licensing boards to suspend or revoke your professional license if you default on your student loans?

Well, until June 30 at least. This year, as part of a larger occupational license reform bill that will make it easier for ex-offenders to receive a license, the legislature adopted new language that will prohibit the state from pulling your license just because you couldn’t make a payment on your student loans.

The old law, and others like it, were meant to limit defaults and to keep borrowers from choosing not to pay back their loans. A “tough love” law, if you will. The U.S. Department of Education even previously urged states to “deny professional licenses to defaulters until they take steps to repayment.”

Mississippi certainly wasn’t alone. Prior to the repeal, the Magnolia State was one of 15 states - both red and blue - that had such a law in place. But the repeal movement has been steadily growing, with five other states scrapping their laws in the last two years.

The reasons for the sudden changes of heart are obvious. Some 44 million Americans owe a collective $1.5 trillion in student loan debt nationwide, with 8.5 million federal borrowers in default as of last year. At a time when more and more individuals are saddled with student loan debt, it makes little sense to attack their ability to earn a living in their professional field. The fastest way, and for most people the only way, to pay off debt is to generate monthly income above the basic cost of living.

When young people lose their income, they lose their ability to pay back loans in any meaningful way. At that point, borrowers are stuck in an endless cycle with no way out and few good options. Such individuals are likely to take on credit card debt or other forms of debt just to stay afloat. Continuing this process keeps a debtor spinning like a hamster in a wheel.

As the student loan crisis is growing, more Americans than ever, and more Mississippians, also need a license to obtain employment. We would call it ironic if it wasn’t so dumb and cruel.

Nearly one-in-five Mississippians need a license to work. This is a change from under five percent just a few decades prior. That is because while licensure was once limited to occupations such as medical professionals, lawyers, or teachers, it now extends to everything from an auctioneer to a shampooer. All totaled, Mississippi licenses 66 lower income occupations.

Naturally, those lower income occupations are more likely to default on student loans.

Consider cosmetologists, who are licensed in all 50 states. In Mississippi, you must clock 1,500 hours, which is more-or-less in line with other states. And you need all this for a job that has a median national wage of $25,000 per year. Not surprisingly, cosmetologists had a national default rate of over 17 percent in 2012, significantly higher than the national average. If a cosmetologist defaults, and he/she loses his/her license, what should they then do? The same could be asked of any licensed professional.

In the long run, we need to reform occupational licensing to make it easier for people to earn a living without spending a year or two in the classroom, often accruing debt. Many of the occupational licenses the state requires are onerous and serve little purpose but to protect established interests. Most occupational licenses can be replaced with less restrictive alternatives such as certification, bonding, insurance, inspections, or registration.

In the meantime, preventing licensing boards from attacking licenses because of student loan default is a good first step toward liberty and toward encouraging a defaulter to take the personal responsibility to pay off debts by exercising their right to earn a living in Mississippi.

This column appeared in the Vicksburg Post on April 24, 2019.

Gov. Phil Bryant has signed the Fresh Start Act, protecting the 14th Amendment right of ex-offenders to obtain gainful employment.

Senate Bill 2781, authored by Sen. John Polk (R-Hattiesburg) and Mark Baker (R-Brandon), prohibits occupational licensing boards from using bureaucratic rules to prevent ex-offenders from working. The law requires occupational licensing boards to eliminate blanket bans and “good character” clauses used to block qualified and rehabilitated individuals from working in their chosen profession.

“Both federal and state courts clearly affirm that occupational licensing boards must provide an objective and legitimate reason to deny an ex-offender a license to work,” said Dr. Jameson Taylor, Vice President for Policy at Mississippi Center for Public Policy. “According to the Mississippi Supreme Court, the freedom to engage in a profession is a ‘God-given, constitutional liberty.’ Mississippi licensing boards need to clean up their rules so they don’t run afoul of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. Fresh Start requires them to do so while leaving every licensing board free to set high standards for their specific profession.”

Under the Fresh Start Act, licensing boards must adopt a “clear and convincing standard of proof” in determining whether a criminal conviction is cause to deny a license. This includes the nature and seriousness of the crime, the passage of time since the conviction, the relationship of the crime to the responsibilities of the position and evidence of rehabilitation. The law also creates a preapproval process that allows ex-offenders to determine if they may obtain a particular license before undertaking the time and expense of training, education and testing. In addition, the law protects licensed individuals who fall behind on their student loans from losing their occupational license.

“We have thousands of open positions available in Mississippi,” said Taylor. “We need skilled labor. We also have one of the highest ex-offender populations in the country. We shouldn’t let red tape prevent people from pursuing their dreams and supporting their families.”

According to a study published by Arizona State University, states with heavier occupational licensing burdens have much higher 3-year recidivism rates. More than 10 states have codified the protections contained in Fresh Start, including Tennessee and Georgia.

“Fresh Start leaves every occupational licensing board free to protect consumer health and safety by maintaining rigorous standards for licensure,” concluded Taylor. “But it also directs licensing boards to follow the Constitution by outlining legitimate reasons to deny someone a license. In the past, broad licensing restrictions have been used to keep “certain kinds of people” from working. Thanks to the leadership of Gov. Phil Bryant, Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves and Speaker Philip Gunn, Mississippi is cutting red tape so that people who want to work can obtain good-paying jobs.”