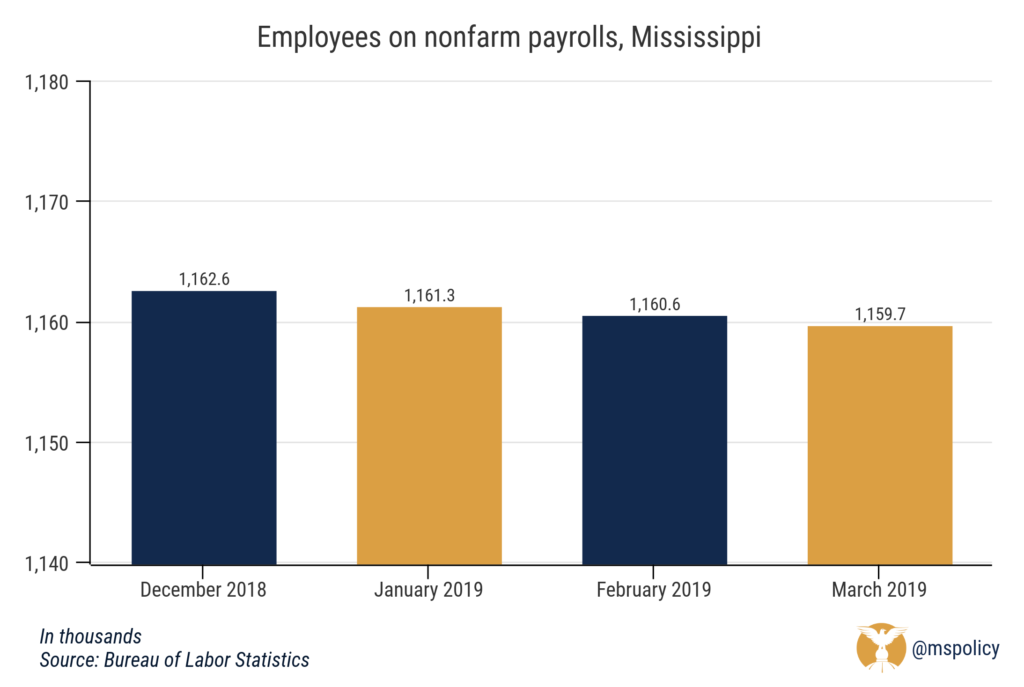

Payrolls in Mississippi dipped in the first quarter of 2019 as the state lost 2,900 jobs from December 2018 through March 2019.

In December, nonfarm payrolls in Mississippi reached 1,162,600. But after three months of decreases, payrolls were down to 1,159,700 in March. Preliminary estimates from February initially showed a slight increase to 1,161,900, but those numbers were revised down to 1,160,600.

This is a reversal of 2018 when Mississippi added about 11,000 jobs for a modest job growth rate of one percent.

Over the past month, Mississippi saw employment gains in construction (+500), financial activities (+100), and leisure and hospitality (+100). However, the state experienced reductions in manufacturing (-500), trade, transportation, and utilities (-400), professional and business services (-400), education and health services (-100), and government (-100).

What is happening nationwide?

Nationally, the country has added around 540,000 jobs over the first three months of the year. Mississippi’s job growth rate of -0.25 percent came in 44th among the 50 states. Among Mississippi’s neighbors, Alabama was the top performer, growing at a rate of 0.47 percent.

| State | Job growth rate | National ranking |

| Alabama | .47% | 17 |

| Arkansas | .28% | 26 |

| Louisiana | .12% | 35 |

| Mississippi | -.25% | 44 |

| Tennessee | .22% | 30 |

For Mississippi’s neighbor to the east, this is a continuing trend of strong numbers. In 2018, Alabama had a job growth rate of 2.13 percent.

Idaho had the greatest percentage change in employment during the first quarter at 1.19 percent, followed by West Virginia (1.05%), North Carolina (.91%), Oregon (.90%), and Maine (.78%).

What can Mississippi do better?

Mississippi has the fourth largest government share of state economic activity, and that is due to state and local spending, not federal funds. While there is a large contingent who would want to see the government spend more, it would actually be pretty difficult.

When the government grows, the state has increased ownership and the private sector shrinks. And economic freedom, which is based on free markets and voluntary exchange, individual liberty, and personal responsibility, wanes.

According to the most recent Fraser Institute Economic Freedom of North America report, which measures government spending, taxes, and labor market freedom, Mississippi was ranked 45th among the 50 states. Similarly, Cato Institute’s Freedom in the Fifty States, which measures economic and personal freedom, placed Mississippi 40th in their most recent rankings.

What is the correlation between economic freedom and prosperity? The freer states are more prosperous, have higher per capita incomes, more entrepreneurial activity, and lower poverty rates. We have the model. Similar states have experienced economic growth by adopting freedom-based policies. And it is important to know the difference between the reality of economic growth and the practice of economic development; those can be very different things. There is a role for corporate recruitment and economic development, but that can’t be the main driver of sustainable economic growth.

Government incentives, often in the name of economic development and being ‘business-friendly,’ attempt to recruit businesses to the state through financial benefits, such as site preparation, infrastructure, job training, or special tax breaks. In most cases, the reason incentives are necessary is because of higher taxes or policies that burden businesses. In some cases, incentives are necessary because corporations take advantage of a highly competitive economic development and play the states against one another. There is a better way for us to play this game.

Instead of special incentives for a few, Mississippi should work to provide a favorable climate for every business. Let the market decide where a business locates or expands. An economic development officer can sell low taxes and low regulatory burdens to a company looking for a great location like Mississippi. What’s more, the data shows us that such policies allow existing businesses, already in our state, to expand and grow from a small employer to a large employer without getting any incentives from the taxpayers. Those are the best jobs. That’s sustainable economic growth.

To their credit, state leaders have attempted to improve the economic climate of Mississippi, most notably through tax and regulatory reform. In 2017, the legislature adopted a new law that will require all new licensing regulations to be approved before they take effect, ensuring new attempts to stifle competition will be reviewed before they are finalized.

And the Taxpayer Pay Raise Act in 2016 will eliminate the three percent income tax bracket, allow self-employed individuals to deduct half of their federal self-employment taxes, and remove the franchise tax on property and capital when fully implemented. Even though Mississippi’s overall tax burden is still above the national average, this will move Mississippi closer to a flatter income tax and make our business climate more competitive.

These reforms weren’t easy, but showed forward thinking to align us closer with neighboring states. Making the case for spending more money on your favorite government program is not a path to prosperity. We need to think much bigger and much smarter. If we want to do better than the bottom ten in categories like per capita income, it starts with doing better in categories like business friendliness, regulatory practices, entrepreneurial environment, private capital encouragement, and tax rates.

It’s common knowledge that Mississippi receives plenty of negative coverage in the news. Whether it's fair or not, Janelle Hederman and her brother, Will, are working to change that.

They view their Airbnb property as a place that provides a positive, engaging, Southern experience for those visiting; a counter to the less than favorable image some have of the state. That’s a good thing.

Janelle and Will have been hosting for five years now. They split the work of the Airbnb half and half. Will, who resides in Texas, handles the online element and bookings, while Janelle restocks the property with necessities and takes care of the things that can’t be done via computer.

The property sits up against the reservoir in Rankin county. Wood paneling lines the walls of the house of this house with a very 60s feel about it. The Hedermans bought the property, which had been in the family, from their cousins six years ago. They knew that such a peaceful location shouldn’t be wasted, but at the time, neither lived in the state. The Hedermans did not want a long-term renter and the property was already furnished so it seemed more economical and efficient to sign on with the then-up and coming Airbnb.

The big question was who would vacation in Rankin county. Over 150 bookings, 600 people, and five years later, that question has been answered.

Guests have ranged from in-state, California, Nebraska, Minnesota, and Kansas, to the United Kingdom and France. They even come from minutes away as in the case of two medical students who initially came for a month to study. They ended up staying for two. The Hedermans have also hosted students and their parents, bass fishermen, softball and soccer teams, family reunions, and wedding rehearsal dinners. They’ve even had people come film music videos and documentaries on the property.

When asked what the draw is about Airbnb, Janelle thinks that it comes down to how economical it is. The Hedermans property has bedding for 12 people, however, it can accommodate more. The sports teams have brought the most in, consisting of 15 or 16 people. In addition to the economy of Airbnb, entertainment is provided. The Hedermans have fishing poles, john boats, and canoes all ready to be taken out on the reservoir, along with plenty of space for kids to run around the yard. It’s all part of the welcoming experience.

While the city of Jackson considers regulations that would drive most Airbnb operators out of town, the Hedermans have already had to fight for theirs. Two years ago, Pearl River Valley Water Supply tried to put an end to Airbnb in the area. In the end, PRV did not succeed in eliminating Airbnb properties, but the issue did bring up concern regarding property rights. Janelle says many neighborhoods already have covenants that address whether residents can rent their property out or not and thinks it should be left that way.

There’s no need for any overhead government or government agency to come in and tell neighborhood residents what they can or can’t do.

According to Janelle, Airbnb is in the middle of a Southern clash; on one hand, Mississippians are friendly and want the comfort of knowing everyone in their neighborhood without strangers coming and going. On the other hand, companies like Airbnb can have a significant impact on economies, which Mississippi needs.

As a resident of Belhaven, Janelle believes Jackson’s economy itself could use a facelift. As to concerns about strangers coming and going, Janelle says Airbnb is based on the premise of the Golden Rule. The company has a system in place to hold everyone accountable. Just like guests have the ability to rate a property and leave a review, hosts can do the same for guests. Once you have a bad review as a renter, there’s little chance a host will be willing to take you on again.

In Janelle’s experience, the majority of Airbnb users are good, honest, hardworking people looking to have a good time and a good experience in a quiet place. Ultimately, Janelle is convinced that the concern of not knowing one’s neighbors should give way to the economic factor.

Janelle is confident that having Airbnb makes people more comfortable in coming to the state, and once they are here, an opportunity to show them all the good happening throughout the state, opens up.

Possibly changing negative minds about Mississippi.

Gov. Phil Bryant has signed legislation that creates a first-in-the-nation tax credit for targeted investments in Mississippi’s foster care system.

Sponsored by Rep. Mark Baker (R-Brandon), The Children’s Promise Act (HB 1613) will provide concrete assistance to nonprofit organizations working on diverse problems around the state, including human trafficking, opioid addiction, and autism.

Dr. Jameson Taylor, Vice President for Policy with the Mississippi Center for Public Policy explains why this legislation is so important: “No one person or entity has all the answers when it comes to foster care. This tax credit will crowdsource the solutions by inviting new donors to support the development of much-needed services to children and families in crisis.”

According to the National Council of Nonprofits, tax incentives for charitable giving generate as much as a 5 to 1 return. Some of the Mississippi nonprofits eligible for this credit receive no government money, meaning that every child they divert from foster care saves money for the state.

One of these is Baptist Children’s Village. Others, like Canopy Children’s Solutions, are leveraging modest grants into multimillion dollar savings for the state. In addition, these nonprofits are generating significant long-term savings by helping to break cycles of abuse, poverty and welfare dependency.

“Due to changes in federal funding, foster care providers are being forced to reorient their services,” said Taylor. “Some of them are closing certain facilities, others are facing closure altogether. The Children’s Promise Act creates an innovative funding model that will help foster care nonprofits proactively work with the Department of Child Protection Services (CPS) to continue to address the challenges raised by the Olivia Y lawsuit.”

In 2018, the legislature passed a $1 million tax credit for individual donations made to nonprofits working with foster care kids, disabled children, and low-income families. This program was based on a successful model in Arizona. HB 1613 expands this individual credit to $3 million. The Children’s Promise Act also creates a $5 million business tax credit targeted toward nonprofits working directly with CPS. Mississippi is the first state in the country to enact a business tax credit for donations to foster care providers.

“This new law will encourage game-changing investments in foster care,” concluded Taylor. “Mississippi is continuing to lead the way in transforming lives and communities by passing best-in-the-nation welfare reform and, then, empowering the private sector to work alongside government in addressing generational poverty.”

The Children’s Promise Act is endorsed by the Mississippi Center for Public Policy, the Mississippi Association of Child Care Agencies, and the Governor’s Faith Advisory Council.

Low unemployment rates, high labor force participation rates, positive employment and labor force changes, and increasing wages define the strong small metro areas in this country.

There are a total of 324 metro areas with less than 1 million people. There are three in Mississippi: Gulfport, Hattiesburg, and Jackson. The Wall Street Journal recently ranked those areas to determine the hottest and coldest markets in the country.

The top markets were as varied and diverse as the country, though it certainly helps to be in the Southeast or the interior West.

Some may roll their eyes at three of the top seven small markets benefiting from today’s oil boom. Odessa, Texas, of Friday Night Lights fame, came in at number five with Lake Charles, Louisiana at number seven. And the number one small metro area? Midland, Texas. Midland has an unemployment rate of 2.3 percent, labor force participation rate of 77.1 percent, a 9 percent employment change, and a 7.4 percent labor force change. Barbers can even make $180,000 a year in the oil boom town. Certainty times are good.

But, the hottest markets extend far beyond oil. The top five markets also include locales such as Greeley, Colorado, Provo, Utah, and Columbus, Indiana. Other growing markets in the Southeast include College Station, Texas, Gainesville, Georgia, and Huntsville, Alabama.

We are in what may be the hottest job market of our lives. The economy has added jobs for 100 consecutive months (though the 20,000 jobs created in February came in low). Unemployment is at its lowest level in 49 years. Both low-skill and high-skill jobs are in-demand and, as a result, salaries are growing.

Yet that isn’t everywhere. Including a large segment of Mississippi.

Mississippi’s three metro areas are, unfortunately, more likely to be on the back half of this list.

Hattiesburg, home to the University of Southern Mississippi and William & Carey University, had the best showing at 154. The unemployment rate is 4.1 percent with a 59.8 percent labor force participation rate. The employment change is 1.5 percent and the labor force change is 0.9 percent.

The state’s capitol city wasn’t far behind at 173. The Jackson metropolitan area has an unemployment rate of 4 percent, with a 61.9 percent labor force participation rate. Employment grew by 1.3 percent and the labor force grew by 0.7 percent.

While Hattiesburg and Jackson were slightly better than stagnant, the Gulfport metro area fared much worse. Among the 324 metro areas, it came in at 282. The unemployment rate is around the state average at 4.8 percent, while the labor force participation rate is 54.1 percent. Employment grew by just 0.2 percent and the labor force contracted, decreasing by 0.4 percent. This made Gulfport one of 93 markets to see their labor force get smaller over the past year.

In Mississippi, growth is largely relegated to pockets, not metro areas.

Oxford and Lafayette county have a booming economy and a low unemployment rate thanks in large part to Ole Miss, but it generally doesn’t extend beyond the county line.

There’s a similar story in officially designated metro areas. In the three-country Hattiesburg metro area, Forrest county has an unemployment rate of 4.7 percent, which is in line with the state average. Lamar county, it’s western neighbor, has one of the lowest unemployment rates in the state at 3.9 percent. Meanwhile, Perry county, which is east of Hattiesburg, has a 6.5 percent unemployment rate.

In the Jackson metro area, unemployment rates range from 3.7 percent in Rankin county to 6.5 percent in Copiah county.

This, of course, isn’t that different than what much of the smaller markets in America are experiencing.

While the Jackson City Council considers an ordinance which could drastically limit Airbnb and other short-term rental properties in the area, Jan Serpente continues to maintain and prepare her cottage in anticipation of her next guests.

She first learned of Airbnb about two years ago, when her youngest son, Sam, suggested she and her husband rent out their recently fixed-up wash house in their backyard. “One year he said, ‘mom, why don’t you rent this out?’” Within the first 24 hours that the space was listed on the Airbnb site, she had her first visitor scheduled. Two years later, she has welcomed and hosted over 200 guests in the Jackson area.

“I think people want to experience their travel, and this gives them an experience,” Jan says.

Jan and her husband moved to Jackson from the Coast after Katrina. Most of the guests she and her husband have hosted are either traveling from Memphis to New Orleans or from Dallas to the beach. A drive, Jan says, that is too long to cover in one day. However, she has also hosted visitors from Cambridge, England; New York; and locals looking for a weekend retreat.

For those visiting the area, Jan leaves out a list of places of interest, restaurant suggestions, and places to explore. Jan and her husband themselves have traveled a bit, though not extensively. Their last stay in a hotel ended when a lawnmower smashed into their room causing them to swear off hotels completely. She says that when someone visits a town, they generally want the local experience of that town. Which is what they get with an Airbnb. With Airbnb, we can give our customers that local town experience.

In Jan’s opinion, Airbnb’s growing popularity comes from a few factors; the comfort level an Airbnb space provides can offer an alternative to a national hotel chain, it generally costs less than a hotel, and an Airbnb can add to a traveler’s experience in ways most hotels just can’t.

Especially important to Jan is the comfort of her guests. She bakes fresh bread every day and makes sure to leave some in the cottage to welcome the guests when they arrive. She also leaves snacks like fruit and instant grits.

“It just makes me happy,” Jan added. “I’ve always liked visitors. I like to make them cozy beds, I like to make good food. So, it’s kind of a spiritual experience that you’re taking care of strangers. You want them to be comfortable, safe, happy. You want it to be a good experience for them.”

By adding to guests’ traveling experience, Jan gets an experience of her own. She describes Airbnb hosting as a way of seeing the world from the comfort of her own home. An experience she loves to share with her granddaughter, who often accompanies her in welcoming guests.

How does a potential renter know if they will be staying in a nice house? Airbnb uses a peer-to-peer review system. If an Airbnb is not up to standards, guests can complain or leave a bad rating. When customers rate a host poorly, that host is likely taken off the Airbnb site completely and kicked out of the system. If a host wants his or her location to stay up on the site, they must provide the best experience possible. This puts the power in the hands of the users and guests who stay at these Airbnb locations, rather than in the hands of government.

We want to keep this power in the hands of the costumers rather than forcing local restrictions on hosts, as various cities in Mississippi, including Jackson, are either attempting to do or have already done.

In Jan’s opinion, the city of Jackson should be doing things to promote Airbnb in Jackson.

“I think we’re doing the city of Jackson a favor,” Jan said. “We’re fabulous ambassadors. Visitors come here for a stay and I want it to be nice for them.”

Considering Jan’s level of constant guests, she is sure that this is what people want. And she enjoys putting on a good face for Jackson. Since moving here over a decade ago, Jan and her husband have considered if they wanted to stay in Jackson on several occasions. Ultimately, there is a lot about Jackson they are both proud of and they want to share that pride with others. Airbnb has given them a way to use their property to do exactly that.

“You kinda want to share that with other people, it’s easy to be here.”

The House and Senate have adopted the conference report to expand Mississippi’s film incentives program despite evidence that the program loses taxpayers money. It is on its way to Gov. Phil Bryant.

Those concerns were largely swept aside by proponents who either argued that the report from PEER was incomplete, inaccurate, or that there are other benefits that we can’t necessarily measure.

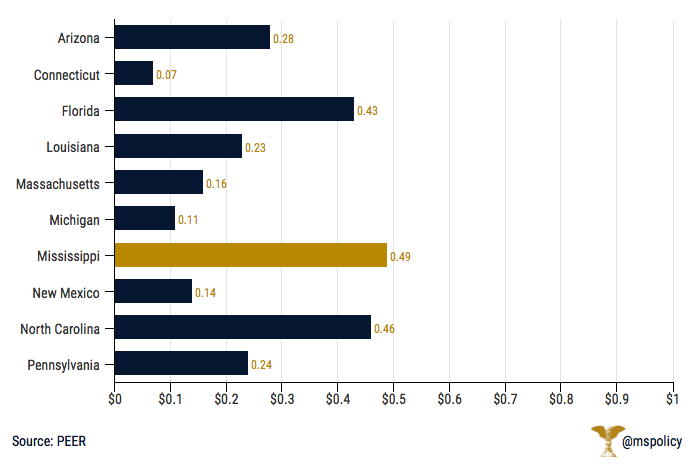

The 2015 report from PEER shows taxpayers receive just 49 cents for every dollar invested in the program. That means that for every dollar the state gives to production companies, we see just 49 cents in return for the general fund.

But Senate Bill 2603, which passed with few dissenting votes, will bring back the non-resident payroll portion of the incentives program. This allows for a 25 percent rebate on payroll paid to cast and crew members who are not Mississippi residents. It expired in 2017 and the Senate had refused to consider it. Until this year. Though the companies now have to be Mississippi-based production companies.

Two other incentive programs remained on the books. One is the Mississippi Investment Rebate, which offers a 25 percent rebate on purchases from state vendors and companies. The other is the Resident Payroll Rebate, which offers a 30 percent cash rebate on payroll paid to resident cast and crew members.

For those who question the PEER report, they are missing one key data point. All the studies on film incentives, and the body of research is significant, have painted a similar picture. We are not sitting on an island with some crazy, unsubstantiated report. As the PEER report outlined, no one is receiving more than 50 cents on every dollar put in the program.

This is why many of those states have scaled back or eliminated their programs. In 2009, all but six states offered some type of incentives for movie producers. As of 2018, just 31 states still have programs on the books. So, while other states are cutting back, Mississippi lawmakers appear interested in pressing forward.

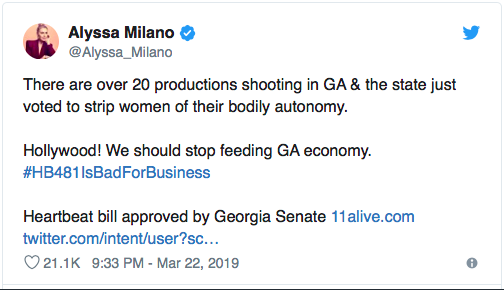

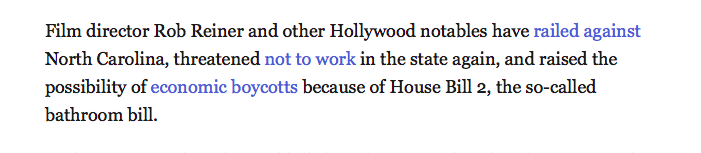

And there is another point to be considered. Do we want Hollywood to think they control our state? That is certainly the emerging situation in Georgia, a state that has a massive film incentives program. Consider this recent tweet from actress Alyssa Milano:

Just last week, Gov. Phil Bryant signed a heartbeat bill into law. Or this commentary from director Rob Reiner concerning North Carolina’s bathroom bill a number of years ago:

When you incentive Hollywood to come to your state, they believe they can and should set policy for your state. If you dare to disagree with their value system, the script they follow is to economically boycott the hand that feeds them. We’ve seen this movie before. It’s not worth the price of admission.

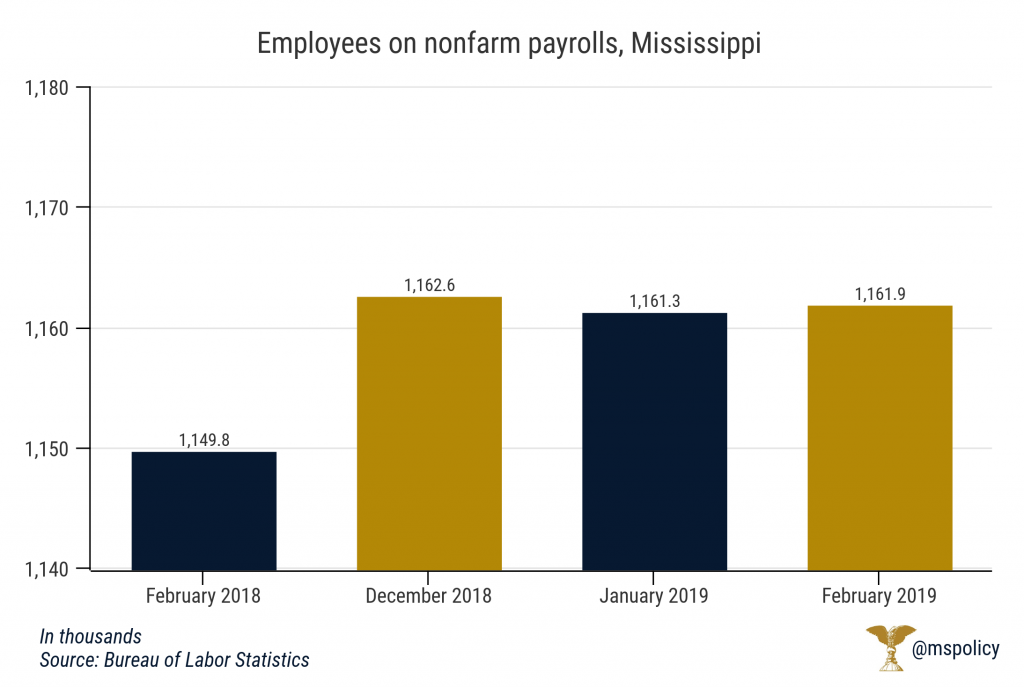

Mississippi saw a slight uptick in the number of jobs last month according to the most recent data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Preliminary estimates show nonfarm payrolls grew from 1,161,300 in January to 1,161,900 in February. This is an increase of over 12,000 from this period one year ago, but down about 700 jobs from two months ago.

The unemployment rate saw a slight increase from 4.7 to 4.8 percent. It is down from 4.9 percent a year ago.

Manufacturing, trade, transportation, and utilities, leisure and hospitality, and government all saw increases in number of jobs over the past month. Construction, professional and business services, and education and health services all posted decreases in number of jobs over the same time period.

Government has now grown by 1,100 jobs year-over-year. Yet, the most recent Census estimates show population in the state was down 3,100 between 2017 and 2018 meaning the state now has more employees to serve less people.

Among neighboring states, Alabama, Arkansas, and Tennessee also had growths in government employment ranging from 200-500 new employees. But they each also had increases in population over the prior year. Louisiana, which loss population last year as well, saw a decrease of 100 jobs in the government sector last month.

Louisiana is also the only neighboring state to have a loss of jobs from December, with a net loss of about 2,000 jobs.

A few years ago, the Mississippi legislature adopted a cottage food operators law, bringing the industry, those who bake goods at home and then sell to the public, into the light.

Cottage food operators, who have annual gross sales of less than $20,000, are given the freedom to sell goodies they bake in their own home, without the government inspecting their kitchen or providing a certificate.

Because of this law, those who had long been baking without asking government now had permission from the state. However, the law is limited. Many states don’t have limits on sales. Mississippi does and such limits are artificially low. Additionally, cottage food operators aren’t allowed to post images of their products for sale on Facebook, Instagram, or anywhere else on the web. These are just two of the many restrictions.

As a result of the internet exclusion, the Department of Health has sent cease and desist letters to the rogue operators who posted pictures of their creations online. The legislature attempted to mend this peculiar prohibition this year.

A bill sailed through the House that would have permitted online postings of food you bake at home. It also slightly raised the cap for gross sales to $35,000. It quietly died in the Senate without a vote.

Who could be against these entrepreneurs trying to earn a living or perhaps making extra money at home? Naturally, the established food industry. The Mississippi Restaurant Association, on their own website, has called the cottage food industry “problematic,” citing “widespread abuse creating an uneven playing field.”

They like to point to the fact that cottage food operators aren’t regulated by the government. That is true. But it that a bad thing? Instead of the cookie police, bakers are best regulated by the free market. An individual who sells an awful-tasting cookie or cake won’t be in business long.

This isn’t much different than the fight to limit food truck freedom. During much of 2018, the city of Tupelo debated restrictions on food trucks that were operating, and thriving, in the city. Were consumers unhappy with the food they were receiving? No, it was the brick-and-mortar restaurants who were unhappy.

The Tupelo city councilmen who were pushing for restrictions acknowledged they were interested in protecting established restaurants. Never mind the fact that any thriving downtown should welcome and encourage food trucks, it is simply not the business of government to prefer one industry, or one sector of an industry, or one participant, over another.

If the residents in Tupelo didn’t want food trucks, there would be no food trucks. All food trucks are doing is responding to market demands. In doing so, they are serving a consumer niche the way any prospering entrepreneur will. Fortunately, the city council relented and didn’t adopt burdensome regulations that would have driven food trucks out of business.

The legislature could have adopted statewide regulations that would have pre-empted local ordinances limiting food trucks, but they, again, decided it was not something they wanted to do.

The legislature also, once again, passed on a bill that would have allowed intrastate sales of agricultural products directly from the producer to consumers and would have prevented local governments from restricting those sales. This would have also opened the door for the legal sale of raw milk for human consumption.

Again, there was a much larger segment of the industry that didn’t want to see small farmers providing competitive pressure. And they won.

Whenever new entrepreneurs enter the arena, whatever that arena might be, the response from the established interests are generally the same. It doesn’t matter whether it’s restaurants not liking food trucks or cottage food operators, the fight waged against Uber and Lyft by the taxi monopolies, or the fight against Airbnb by the hotel lobby, incumbents will always seek government partners to protect their positions. We should recognize it when we see it.

Every incumbent industry will portray their request for protection as merely seeking fairness or consumer safety. But taxpayers are not simpletons; they are on to this game. They understand that much of these regulatory hurdles are about defending the insider’s market.

Unfortunately for consumers, too often the response by lawmakers is to agree to protect the established interests rather than letting the market choose the winners and losers. That was certainly the case this year.

This column appeared in the Commercial Dispatch on March 20, 2019.

The recent scandal regarding celebrities and the elite class and the college admissions of their children has riled up many as we wonder about the deserving child who was left out in favor of an undeserving child.

But even before this scandal, we knew Americans believed the primary consideration for college admissions should be high school grades.

This common belief runs directly against the narrative of Ivy League institutions, and many others, where the trap of identity-based admissions has affected both the highest and lower margins of applicants. However, this belief has reached the point where one ethnic group is being discriminated against simply for being exceptionally talented at achieving high grades.

Affirmative action was designed to provide a remedy to long-standing discrimination allowing schools “considerable deference” in how they select students. This concept of considerations to race and identity in education has been debated extensively in the courts.

These court battles began in 1978 with University of California v. Bakke to Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, which may soon make it to the U.S. Supreme Court. The latter case is redefining the generational debate about affirmative action. Unlike other cases, which have questioned if students on the margins can be rejected so that diversity may be preserved at universities, Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard asks if minority students that excel, can be discriminated against because of their race, specifically Asian students.

Harvard contends that the lawsuit is frivolous as Asians make up roughly six percent of the national population while making up more than 17 percent of Harvard students. Yet Harvard’s own argument is used against it by Students for Fair Admissions, who contend that Harvard’s knowledge of this led the university to discriminate against highly qualified Asian applicants in favor of non-Asian students. Essentially, Harvard’s case is that they have too many Asians.

While schools are granted privilege to foster “equality” in admissions, courts have consistently denied any effort to employ quotas or “racial-balancing” in admission considerations. If the accusations against Harvard are true, it is likely the U.S. Supreme Court will find the university went beyond the law. Regardless, the ruling here will likely have a big impact on future cases involving race-based, university admission policies.

Harvard does make a very good point in its lawsuit; they suffer from an over-representation of exceptionally talented applicants for admission. How awful it must be for them.

Suggesting that some people are just “too good” to be Harvard students could be seen as a symptom of the current times, yet it is more likely this sort of discrimination is a byproduct of the current structure of affirmative action. Diversity in education has proven to be beneficial, but not when the definition of diversity is narrowly confined to the color of skin or the country of origin. When diversity is programmatically enforced by an intentionally vague policy, you can bet actual diversity is not the goal; alterations to student populations based on emotional appeals are.

Such admission policies can be incredibly dangerous to colleges and Harvard has emerged as the face of it. Asian students often outperform white students (and every other race and ethnicity) on academic and extracurricular metrics. This is no secret in the Ivy League community, yet they lag far behind on personal appeals. The mysterious conglomeration of factors, which qualifies some to be Ivy League material and others not, is curiously subjective. And the plaintiffs, Students for Fair Admissions, have made the argument that such policy is inherently discriminatory.

Students, regardless of who they are and where they come from, should be judged by their academic records, their extracurricular accomplishments, and their personal references from school officials/teachers/coaches who know them best, not by arbitrary factors. The result of Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard will likely impact admissions policy significantly. Let’s hope it rewards students who apply for admission based on the quality of their records and not the color of their skin or the country of their origin.