The legislature is very close to reinstating a provision in the film incentives program that died two years ago. And, in doing so, continuing and expanding a program that we know is losing taxpayer dollars.

Senate Bill 2603 has passed the Senate, and, last week, the House, with only minor changes that will need to be resolved before a bill is sent to Gov. Phil Bryant for his signature.

Mississippi currently has two incentives on the books. One is the Mississippi Investment Rebate, which offers a 25 percent rebate on purchases from state vendors and companies. The other is the Resident Payroll Rebate, which offers a 30 percent cash rebate on payroll paid to resident cast and crew members.

Previously, Mississippi had a non-resident payroll portion of the incentives program. This allows for a 25 percent rebate on payroll paid to cast and crew members who are not Mississippi residents. It expired two years ago, and the Senate has refused to consider it after passing the House twice.

It’s a different story this year.

A terrible return on investment of taxpayer dollars

A 2015 PEER report shows taxpayers receive just 49 cents for every dollar invested in the program. That means that for every dollar the state gives to production companies, we see just 49 cents in return. If you or I were receiving that return on our personal investments, we would fire our financial advisor. Of course, no one spends his or her own money as carefully as the person to whom that money belongs.

For those looking at a bright side, we are actually “doing better” than many other states. This includes our neighbors in Louisiana, who recover only 14 cents on the dollar. They also have one of the most generous programs in the country; it was unlimited until lawmakers capped it a couple years ago. (Other reports show the Pelican State recovering 23 cents on the dollar, but either way it’s a terrible investment.)

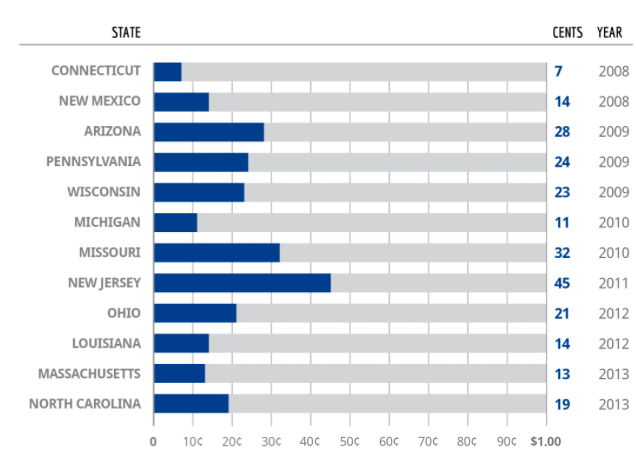

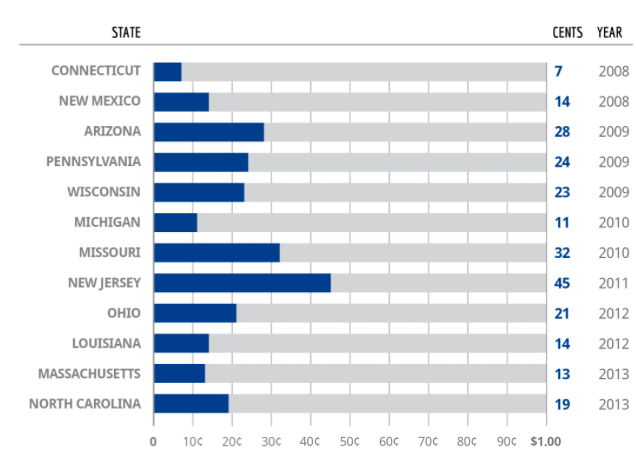

Beyond Mississippi and Louisiana, film incentives are a poor investment throughout the country. Numerous studies have been conducted on film incentives. All sobering for those worried about taxpayer protection. Here is a review of the return per tax dollar given, from 2008 through 2013. In these third-party studies, covering 12 different states, there was not a program that returned even 50 cents on the dollar.

Source: John Locke Foundation

Since this chart was published, studies on similar programs in Florida, Virginia, and West Virginia have shown similar results. No program had a positive ROI.

We have to do it if other people are

One of the commonly prescribed reasons for why need film incentives is it’s “good” for the state to have movies filmed here. As is often the case in government, we focus on the inputs. How many films are made here? What movie star was in Mississippi? That is nice, but the focus should be on outcomes.

The other common argument is that other states are doing it. Throughout the country, producers hold states hostage and threaten to move without incentives. Producers in Mississippi have raised the same point. Again, that is not good reason to essentially throw taxpayer money away.

Simply because another state is wasting money does not mean Mississippi should join them, or continue this practice.

In a comprehensive list of state film production incentives compiled by the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL), we see states that do not have incentives for producers but offer tax breaks to everyone, without partiality. For example:

Alaska: No film incentive program. Effective July 1, 2015, the film production incentive program was repealed. Alaska has no state sales or income tax.

Delaware: No film incentive program. However, the state does not levy a sales tax.

Florida: This program sunset on June 30, 2016. It has not been renewed. The state does not levy a state income tax.

New Hampshire: No film incentive program. The state has no sales and use, or broad base personal income taxes.

South Dakota: No film incentive program. There is no corporate or personal income tax in South Dakota.

Our goal should be for Mississippi to have the most competitive business climate in the country. The tax breaks that a few chosen industries or companies receive should be made available to all. When we do that we will remove the need for taxpayer funded incentives.

Few items are more popular or numerous in the legislature than income or sales tax exemptions.

This year is no different. Numerous bills, introduced by both Democrats and Republicans, have been offered to exempt the sales tax on the retail sales of school supplies sometime between the last week of July and the first week of August. This will go along with the current sales tax holiday for clothing and footwear purchased in the last week of July.

There have been proposals for tax credits for child care expenses, for companies that hire ex-offenders, for grocers who purchase locally grown food or open supermarkets in “food deserts,” for certain hotel renovations, for businesses to open in certain corridors, for people who purchase certain homes in certain areas, for being a volunteer firefighter, for alternative fuel infrastructure, for being a “small town teacher,” for storm shelters, for ports and airport facilities, for locating a headquarters to this state, and the list goes on and on.

Notably, the House has already passed what is known as the “Mississippi Education Talent Recruitment Act,” the legislature’s response to “brain drain.” If enacted, recent graduates will be able to receive up to the full amount of their individual state income tax liability after they work in the state for five years.

At Mississippi Center for Public Policy, we want taxes to be as low as possible. But rather than limiting the Mississippi Education Talent Recruitment Act to someone who has graduated in the past two years, it should be available to everyone in the state and maybe we call it the “Mirror the Tennessee Income Tax Rate Act.”

Tennessee, of course, doesn’t charge an income tax. And they certainly don’t require you to own property, or complete additional hurdles, to receive a full credit as this proposal would. If you don’t own property, don’t own your own business, or you aren’t a teacher, you would only be eligible for a 50 percent rebate. Nor do you have to wait five years to receive the rebate in Tennessee. You just never pay income taxes.

It works well for the Volunteer State.

The intention of this tax exemption proposal is noble. The other examples range from good to silly, but the need for all these exemptions tells us one thing: Our current tax policies are not competitive. Therefore, we have to do something about it to attract (insert whatever you think the state should try to attract).

We have taken the approach that the only way to attract people is through individual incentives. Which, unfortunately, requires entrepreneurs to focus on favor-seeking in the legislature rather than on improving products and services and growing their business through market-based competition. Playing the game in such a manner gives the state more power and the ability to play favorites, essentially picking winners and losers, thus giving the consumers less power.

By following the lead of high-growth, low-tax states in the Southeast that have lower taxes, lighter licensure and regulatory burdens, and a smaller government, we will be able to offer opportunities for people regardless of their age or their industry.

Mississippi is one of the numerous states that offer taxpayer funded film incentives to Hollywood producers in an attempt to have movies shot in the Magnolia State.

And, the prospect of a movie star eating at a local restaurant or a movie being filmed in your home town is appealing to most people. Yet it shouldn’t be funded by taxpayers.

There are two programs on the books. One is the Mississippi Investment Rebate, which offers a 25 percent rebate on purchases from state vendors and companies. The other is the Resident Payroll Rebate, which offers a 30 percent cash rebate on payroll paid to resident cast and crew members.

A third rebate, a 25 percent rebate on payroll paid to cast and crew members who are not Mississippi residents, expired two years ago. But lawmakers seem very interested in reviving it this year.

So, who could be against this? For one, taxpayers ought to be. Film incentives are a losing proposition. And that is according to the state’s own data.

A 2015 PEER Report shows taxpayers receive just 49 cents for every dollar invested in the program. That means that for every dollar the state gives to production companies, we see just 49 cents in return. If you or I were receiving that return on our personal investments, we would fire our financial advisor. Of course, no one spends his or her own money as carefully as the person to whom that money belongs.

An ironic, or perhaps sad, side note is that we are actually “doing better” than other states when it comes to film incentives. This includes our neighbors in Louisiana, who recover only 14 cents on the dollar. They also have one of the most generous programs in the country; it was unlimited until lawmakers capped it a couple years ago. Other reports show the Pelican State recovering 23 cents on the dollar, but either way it’s a terrible investment.

Beyond Mississippi and Louisiana, film incentives are a poor investment throughout the country. Numerous studies have been conducted, all providing sobering statistics for those worried about spending tax dollars wisely.

For every dollar spent, Connecticut receives just 7 cents in return, Michigan receives 11 cents, Massachusetts receives 13 cents, New Mexico receives 14 cents, North Carolina receives 19 cents, Ohio receives 21 cents, and Wisconsin receives 23 cents. We could go on.

Studies from numerous other states over the past decade show taxpayers losing wherever film incentives have been tried. That is the reason many of those states have scaled back or eliminated their programs. In 2009, all but six states offered some type of incentives for movie producers. Today, just 31 states still have programs on the books. So, while other states are cutting back, Mississippi lawmakers appear interested in pressing forward.

How do these states, which no longer offer incentives, try to attract movie producers?

Alaska, for example, repealed their program in 2015. But they advertise their lack of state sales or income tax. Similar story in Florida, who let their program expire in 2016. They do not levy a state income tax.

There are many reasons Mississippi is attractive for filming. It is the quintessential Southern state with historic squares along with beautiful antebellum mansions. There is the vast farmland of the Delta, the beaches of the Coast, and the numerous forests throughout the state. Mississippi has the lowest cost-of-living in the country and it is a right-to-work state with very competitive wages. We have plenty to sell.

One lawmaker recently called it “criminal” that the movie Free State of Jones, a movie about Mississippi, was not filmed in Mississippi. We lost out in the race-to-the-bottom bidding war with Louisiana. We should consider it criminal that lawmakers are so willing to part with our tax dollars in a losing endeavor.

Rather, our goal should be for Mississippi to have the most competitive business climate in the country. The tax breaks that a few chosen industries or companies receive should be made available to all.

When we do that we will remove the need for taxpayer funded incentives.

This column appeared in the Daily Leader on February 14, 2019.

At a time when most states are cutting back or eliminating film incentives, Mississippi is pressing forward.

Yesterday, both the House and Senate adopted separate legislation that would reinstate the nonresident payroll portion of the incentives program. This would allow for a 25 percent rebate on payroll paid to cast and crew members who are not Mississippi residents.

It was repealed in 2017, when the Senate did not consider renewing it. It is a different story this year.

If the expired incentive is brought back, it would put Mississippi in the position of expanding film incentives program while other states are putting on the breaks. In the past decade, the number of states with such a program has declined from a peak of 44 to 31 (as of last year).

Why are states moving away from film incentives? The answer is simple; the math doesn’t add up.

A 2015 PEER report shows taxpayers receive just 49 cents for every dollar invested in the program. That means that for every dollar the state gives to production companies, we see just 49 cents in return.

If you’re a proponent of these incentives and you’re looking for a bright side, we are actually “doing better” than many other states. This includes our neighbors in Louisiana, who recover only 14 cents on the dollar. They also have one of the most generous programs in the country; it was unlimited until lawmakers capped it a couple years ago. (Other reports show the Pelican State recovering 23 cents on the dollar, but either way it’s a terrible investment.)

Beyond Mississippi and Louisiana, film incentives are proving to be a poor investment throughout the country. Numerous studies have been conducted on film incentives. Each of them has produced sobering results for those worried about taxpayer protection. Here is a review of the return per tax dollar given, from 2008 through 2013. In these third-party studies, covering 12 different states, there was no program that returned even 50 cents on the dollar.

Source: John Locke Foundation

Since this chart was published, studies on similar programs in Florida, Virginia, and West Virginia have shown similar results. No program had a positive ROI.

Having a movie filmed in your state is a nice trophy, as is having a movie star dining at a local restaurant. But when it comes to our tax dollars, the burden on the state should be to demonstrate how those dollars are being wisely invested.

Other states appear to be focused on results of film incentives. Mississippi, however, appears to be ignoring the data and heading in the opposite direction.

Right now in Mississippi, the sale of raw cow’s milk for human consumption is prohibited, but a bill in the Mississippi legislature could change that.

The Mississippi On-Farm Sales and Food Freedom Act, authored by state Rep. Dan Eubanks (R-Walls) would allow intrastate sales of agricultural products directly from the producer to consumers and would prevent local governments from restricting those sales.

The bill would also mandate a “buyers beware” label for these goods that would warn of health risks from consuming raw, unprocessed agricultural products.

The bill is up against a deadline, as Tuesday is the deadline for bills to pass out of committee.

According to Eubanks, Mississippians are spending $8.5 billion a year on food and most of that is imported from out of state.

“Ninety percent of our food we import and we’re an ag state,” Eubanks said. “The irony is we’ll commit billions in taxpayer money on incentives and bond issues to bring in economic development and you might get 500, 1,000 jobs.

“All we’ve got to do is make a little change to our law, wouldn’t cost us a dime. If we started buying five percent more locally grown, you’re talking $400 million plus that would stay in our state. If it stays in our state, it would create jobs.”

He says that passage of this bill would allow the birth of a cottage farm industry in the state and help small farms grow into larger operations.

He also says that it’s absurd that the state sells cigarettes with a disclaimer on each box about their health effects, but won’t allow its citizens to buy raw milk. Also, it’s legal in the state for consumers to buy raw goat’s milk.

“We put such an impediment in the way of people trying to live healthier,” Eubanks said. “We’re the unhealthiest state in the country. We consume so much processed, artificial foods and we need to eat more whole, natural foods and yet we want to put a road block in the way to helping further that for some communities.”

As for neighboring states, Alabama and Louisiana prohibit all sales of raw milk for human consumption while Arkansas allows the on-farm sale of up to 500 gallons of raw milk. Tennessee only allows raw milk to be obtained through what is known as a “cow share agreement” where an individual or a group pay a farmer for boarding and milking a cow that they own.

Nationally, 13 states allow sale of raw milk in stores while 17 states allow sales only on the farm where it was produced.

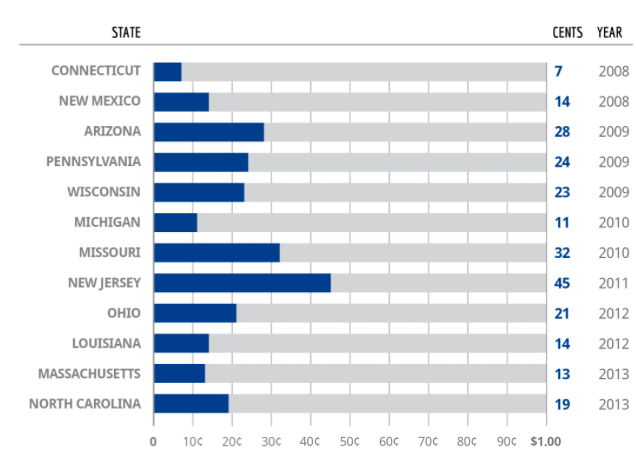

Mississippi had a job growth of 1 percent last year.

According to preliminary data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Mississippi added about 11,000 jobs last year. But while Mississippi did experience an increase in job growth, the state lagged behind every neighboring state.

Of the four neighboring states, Alabama had the strongest job growth at 2.13. Tennessee was next at 2 percent, followed by 1.37 percent in Arkansas, and 1.1 percent in Louisiana.

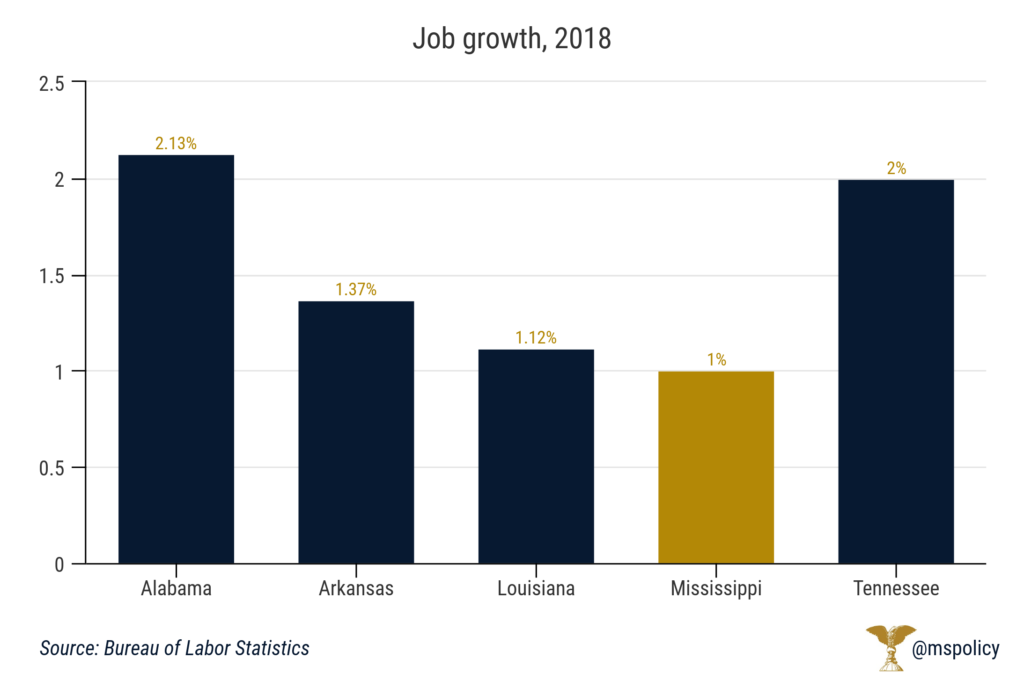

Of the 11,000 jobs Mississippi added last year, about 1,400 were in government. Professional and business services had the strongest growth (5,300), followed by leisure and hospitality (3,600), and manufacturing (2,000).

Education and health services added a modest 300 jobs and construction did not any jobs. Financial activities had a loss of jobs (-100) as did trade, transportation, and utilities (-1,900).

Mississippi’s unemployment rate, which is historically among the highest in the country, sits at 4.7 percent. It’s down slightly from 4.8 percent last December, but still higher than the national average of 3.9.

What can Mississippi do better?

Mississippi has the fifth largest government share of state economic activity, and that is due to state and local spending, not federal funds. While there is a large contingent who would want to see the government spend more, it would actually be pretty difficult.

When the government grows, the state has increased ownership and the private sector shrinks. And economic freedom, which is based on free markets and voluntary exchange, individual liberty, and personal responsibility, wanes.

According to the most recent Fraser Institute Economic Freedom of North America report, which measures government spending, taxes, and labor market freedom, Mississippi was ranked 45th among the 50 states. Similarly, Cato Institute’s Freedom in the Fifty States, which measures economic and personal freedom, placed Mississippi 40th in their most recent rankings.

What is the correlation between economic freedom and prosperity? The freer states are more prosperous, have higher per capita incomes, more entrepreneurial activity, and lower poverty rates. We have the model. We need to just look at what similar states have done for economic growth. And it is important to know the difference between the reality of economic growth and the practice of economic development; those can be very different things.

Government incentives, often in the name of economic development and being ‘business-friendly,’ attempt to lure businesses to the state through financial benefits, such as site preparation, infrastructure, job training, or special tax breaks. The only reason these incentives are necessary is because of higher taxes or policies that burden businesses.

Instead of special incentives for a few, Mississippi should work to provide a favorable climate for every business. And let the market decide where a business locates or expands. An economic development officer can sell low taxes and low regulatory burdens to a company looking for a great location like Mississippi. What’s more, the data shows us that such policies allow existing businesses already in our state to expand and grow from a small employer to a large employer without getting any incentives from the taxpayers. That’s economic growth.

Being business friendly isn’t based on who can seek the most favors, it is based on how free your state is.

To their credit, state leaders have attempted to improve the economic climate of Mississippi, most notably through tax and regulatory reform. In 2017, the legislature adopted a new law that will require all new licensing regulations to be approved before they take effect, ensuring new attempts to stifle competition will be reviewed before they are finalized.

And the Taxpayer Pay Raise Act in 2016 will eliminate the 3 percent income tax bracket, allow self-employed individuals to deduct half of their federal self-employment taxes, and remove the franchise tax on property and capital when fully implemented. Even though Mississippi’s overall tax burden is still above the national average, this will move Mississippi closer to a flatter income tax and make our business climate more competitive.

These reforms weren’t easy, but showed forward thinking to align us closer with neighboring states. Making the case for spending more money on your favorite government program is not what is needed to prosper. We need to think much bigger than that. If we want to do better than the bottom ten in categories like per capita income, it starts with doing better in categories like business friendliness, regulatory practices, and tax rates.

Thanks to a recent change in federal regulations for short-term health insurance policies, Mississippians could have a chance to purchase cheaper policies.

In August, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services issued a rule that extended the duration of short-term plans from three months to 12, with renewals that could stretch them out for up to three years. The policy went into effect in October.

According to HHS data, the monthly premium for a short-term policy in the fourth quarter of 2016 was $124, compared with $393 for an unsubsidized individual market plan.

Mississippi Insurance Commissioner Mike Chaney said these policies fill what he called a “doughnut hole” in the market place, where they are between jobs and do not have the ability to pay the high cost of temporary health insurance, known as COBRA (Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985).

He said a few thousand Mississippians at the most would be buying these policies, but having their availability means they have a chance to buy affordable health insurance that was previously unavailable. He also said several insurance companies are already offering the policies in the Magnolia State.

“It fills a very needy void in the market,” Chaney said. “It gives the consumer another choice. You need to be certain your doctor will accept the policies and they need to be certain to what will and won’t be paid. We’ve not had any complaints on them.”

These policies also could be utilized by seniors not eligible for Medicare and young adults who have aged out from their parents’ plans.

According to a report by the Foundation for Government Accountability, yearly premiums for health insurance have skyrocketed from an average of $2,800 in 2013 to $6,000 in 2017 and more than 30 million remain uninsured. The report also says that 56 percent of counties in the U.S. had only one insurer to choose from in the individual market.

The rule change will help 2.5 million gain health insurance, according to the FGA.

Mississippi is one of 17 states with no restrictions in state law that would limit the plans.

These short-term plans are much cheaper for consumers, but lack some of the mandated coverages that are part of the policies sold under the exchanges set up by the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare. This means these plans can be better tailor-fit to a consumer’s need than the several sizes fit-all types offered by the exchanges.

Film incentives are one of the few programs that are largely popular among legislators regardless of party, while they universally provide a poor return on investment for taxpayers.

There was a time when most states had some kind of incentives for the film industry, but that trend has quickly changed. While 44 states had incentives a decade ago, today just 31 do. Others, like Mississippi, have quietly scaled back their program.

For the past two sessions, the Senate has killed attempts from lawmakers in the House to extend the non-resident payroll portion of the incentives program. This previously allowed for a 25 percent rebate on payroll paid to cast and crew members who are not Mississippi residents.

Two incentives remain on the books. One is the Mississippi Investment Rebate, which offers a 25 percent rebate on purchases from state vendors and companies. The other is the Resident Payroll Rebate, which offers a 30 percent cash rebate on payroll paid to resident cast and crew members.

House Bill 1128 would bring back the non-resident rebate. Lawmakers should proceed with caution.

A terrible return on investment of taxpayer dollars

A 2015 PEER report shows taxpayers receive just 49 cents for every dollar invested in the program. That means that for every dollar the state gives to production companies, we see just 49 cents in return. If you or I were receiving that return on our personal investments, we would fire our financial advisor. Of course, no one spends his or her own money as carefully as the person to whom that money belongs.

For those looking at a bright side, we are actually “doing better” than many other states. This includes our neighbors in Louisiana, who recover only 14 cents on the dollar. They also have one of the most generous programs in the country; it was unlimited until lawmakers capped it a couple years ago. (Other reports show the Pelican State recovering 23 cents on the dollar, but either way it’s a terrible investment.)

Beyond Mississippi and Louisiana, film incentives are a poor investment throughout the country. Numerous studies have been conducted on film incentives. All sobering for those worried about taxpayer protection. Here is a review of the return per tax dollar given, from 2008 through 2013. In these third-party studies, covering 12 different states, there was not a program that returned even 50 cents on the dollar.

Source: John Locke Foundation

Since this chart was published, studies on similar programs in Florida, Virginia, and West Virginia have shown similar results. No program had a positive ROI.

We have to do it if other people are

One of the commonly prescribed reasons for why need film incentives is it’s “good” for the state to have movies filmed here. As is often the case in government, we focus on the inputs. How many films are made here? What movie star was in Mississippi? That is nice, but the focus should be on outcomes.

The other common argument is that other states are doing it. Throughout the country, producers hold states hostage and threaten to move without incentives. Producers in Mississippi have raised the same point. Again, that is not good reason to essentially throw taxpayer money away.

Simply because another state is wasting money does not mean Mississippi should join them, or continue this practice.

In a comprehensive list of state film production incentives compiled by the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL), we see states that do not have incentives for producers but offer tax breaks to everyone, without partiality. For example:

Alaska: No film incentive program. Effective July 1, 2015, the film production incentive program was repealed. Alaska has no state sales or income tax.

Delaware: No film incentive program. However, the state does not levy a sales tax.

Florida: This program sunset on June 30, 2016. It has not been renewed. The state does not levy a state income tax.

New Hampshire: No film incentive program. The state has no sales and use, or broad base personal income taxes.

South Dakota: No film incentive program. There is no corporate or personal income tax in South Dakota.

Our goal should be for Mississippi to have the most competitive business climate in the country. The tax breaks that a few chosen industries or companies receive should be made available to all.

When we do that we will remove the need for taxpayer funded incentives.

The Mississippi House has passed legislation that will allow cottage food operations to expand in the state.

House Bill 702 would help cottage food operators by increasing the maximum annual gross sales to $35,000 and authorize them to advertise online. Both are now headed to the Senate for committee assignment, likely the Senate Agriculture Committee.

Cottage food operators are defined by the Mississippi Department of Health as those who sell non-perishable foods made in their home kitchens such as candy, cookies, pies, cakes, dried fruit, trail mix, jams and jellies and popcorn.

Right now, cottage food operators are limited to $20,000 in gross annual sales. They were removed from state regulations by Senate Bill 2553 in 2013.

HB 702 was authored by state Rep. Casey Eure (R-Saucier) and passed 116-0, with one present vote.

According to a 2018 report by the Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation at Harvard University Law School, Mississippi ranks in the middle tier among states when it comes to cottage food sales.

Mississippi allows direct sales to consumers, but not indirect sales (to restaurants, retail and wholesale).

Twelve states allow both indirect and direct sales to consumers.

Mississippi is in the lower tier at present for annual sales limits and would move up to the next tier (annual sales of $30,001 to $50,000) if Gov. Phil Bryant signs HB 702 into law.

Arizona, Arkansas, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Massachusetts, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia and Wyoming don’t have any annual restrictions on cottage food sales.

The bill would also remove the prohibition on advertising their products online, allowing operators to run a website or post pictures on social media.

The other food-related bill of the day, HB 793, would prohibit producers from labelling any food produced or cultured from animal tissue and plant- or insect-based food products as meat.

State Rep. Bill Pigott (R-Tylertown) wrote HB 793 and it also passed 116-0.

Meat grown in a laboratory, according to a July report by the Associated Press, could be on the market by 2021. A Dutch company, Mosa Meat, said it had the funds to get the product — which is made from a small sample of cells taken from a live animal and fed nutrients so they grow into strands of muscle tissue — into stores.

According to the story, the company claims it could make up to 80,000 quarter pounders from a single sample.