School choice advocates rallied on the south steps of the state Capitol Tuesday to celebrate past legislative victories and press the legislature for further expansion.

Both Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves and House Speaker Philip Gunn spoke at the rally, which was attended by school children from around the state.

“This is not about politics, but people,” Reeves said. “It’s about giving parents more options for their kids. I believe that parents know best what’s best for their kid, not some bureaucrat sitting in Jackson.

“It should not matter what a kid’s zip code is or what their mom or dad does for a living. Every kid in our state deserves a chance at success and this is about ensuring that every kid gets that opportunity.”

The Legislature has made key strides in the past seven year in furthering school choice statewide.

Gov. Phil Bryant signed into law a bill in 2012 that created a scholarship for children with dyslexia. The next year, he signed a bill that authorized the creation of charter schools. In 2015, the state’s education scholarship program for children with special needs was signed into law by Bryant.

There are now five charter schools in the state. Only one — Clarksdale Collegiate Public Charter School — is outside the Jackson metro area.

Reeves said he supports expanded funding for the ESA program, which will expire in 2020. This means the Legislature will need to pass a reauthorizing bill in this session or the next to keep it alive.

Due to funding restraints, the ESA program is open to less than 500 students with special needs, and parents can use an allotted $6,637 on tuition, tutors, books and other educational aids. Many sit on a waiting list.

Cleveland mother Leah Ferretti, who has two sons with dyslexia, spoke at the rally and asked attendees if they knew any program like the ESA one that has a 91 percent parent satisfaction rating in the PEER report.

“The door is closing on our babies in 2020 unless the repealer is removed,” Ferretti said. “Our program needs a new funding mechanism so it can meet the growth and the need we are desperately asking for.

“We’re calling on you legislators to allow every student in Mississippi the opportunity to succeed and not be confined to in an environment that is discriminatory or denies their civil rights.”

Also a recent report by the Joint Legislative Committee on Performance Evaluation and Expenditure Review (PEER) spotlighted several issues with the ESA program that could be helped with action by the Legislature.

Right now, the program’s unused funds don’t roll over from one year to the next and instead go back to the general fund. The program uses a lottery system to decide what families receive the money and PEER recommends adding prioritization for families that have been on the wait list.

Also, PEER said that the Mississippi Department of Education hasn’t administered the program as effectively as possible by prioritizing those with active individualized education program as required under law.

According to PEER, as of June 29, there were 197 students on the waiting list. Since most scholarship recipients from the year previous will continue in the program, there are only a few slots that open up for new enrollees each year. As of August, there were only 47 open slots.

In fiscal 2018, taxpayers disbursed $2,057,815 for the ESA program, with 94 percent being spent on tuition, with the rest spent on education aids such as software or textbooks.

A new national survey shows that Americans continue to support school choice.

As National School Choice Week kicks off, polling from the national polling firm Beck Research on behalf of the American Federation for Children, finds that 63 percent of Americans “giving parents the right to use the tax dollars designated for their child’s education to send their child to the public or private school which best serves their needs.”

While school choice is often considered both partisan and controversial, and certainly receives more negative than positive press, it is supported by 72 percent of Hispanic voters, 66 percent of African American voters, and 61 percent of white voters. Ideologically, 75 percent of Republicans back school choice, as do 62 percent of independents and 54 percent of Democrats.

On specific questions, polling finds:

- 67 percent of Americans support a federal tax credit scholarship;

- 77 percent of Americans support school choice options for active military members;

- 75 percent of Americans support education savings accounts;

- 83 percent of Americans support school choice programs for students with special needs; and

- 72 percent of Americans support public charter schools.

This year, some 40,000 National School Choice Week events are planned throughout the country. The goal is to raise public awareness of all types of education options for children, including traditional public schools, public charter schools, magnet schools, online learning, private schools, and homeschooling.

The largest event in Mississippi will be held at the State Capitol on Tuesday, January 22.

New Census data shows income tax free states as the big winners when it comes to adding residents.

Because of our federalist system, we have 50 states competing with one another for talent, opportunity, and economic resources. Each state is largely free to dictate what they believe is the appropriate level of taxation, regulation, and size of government.

The annual Census estimates help answer the questions of what Americans prefer. With the most recently released data, we once again see low-and-no-income tax states growing.

The two hardest-hit states were New York and Illinois, which lost 48,000 and 45,000 residents, respectively. These states, home to the largest and third largest cities in the country, are both known for burdensome regulations and outsized taxes.

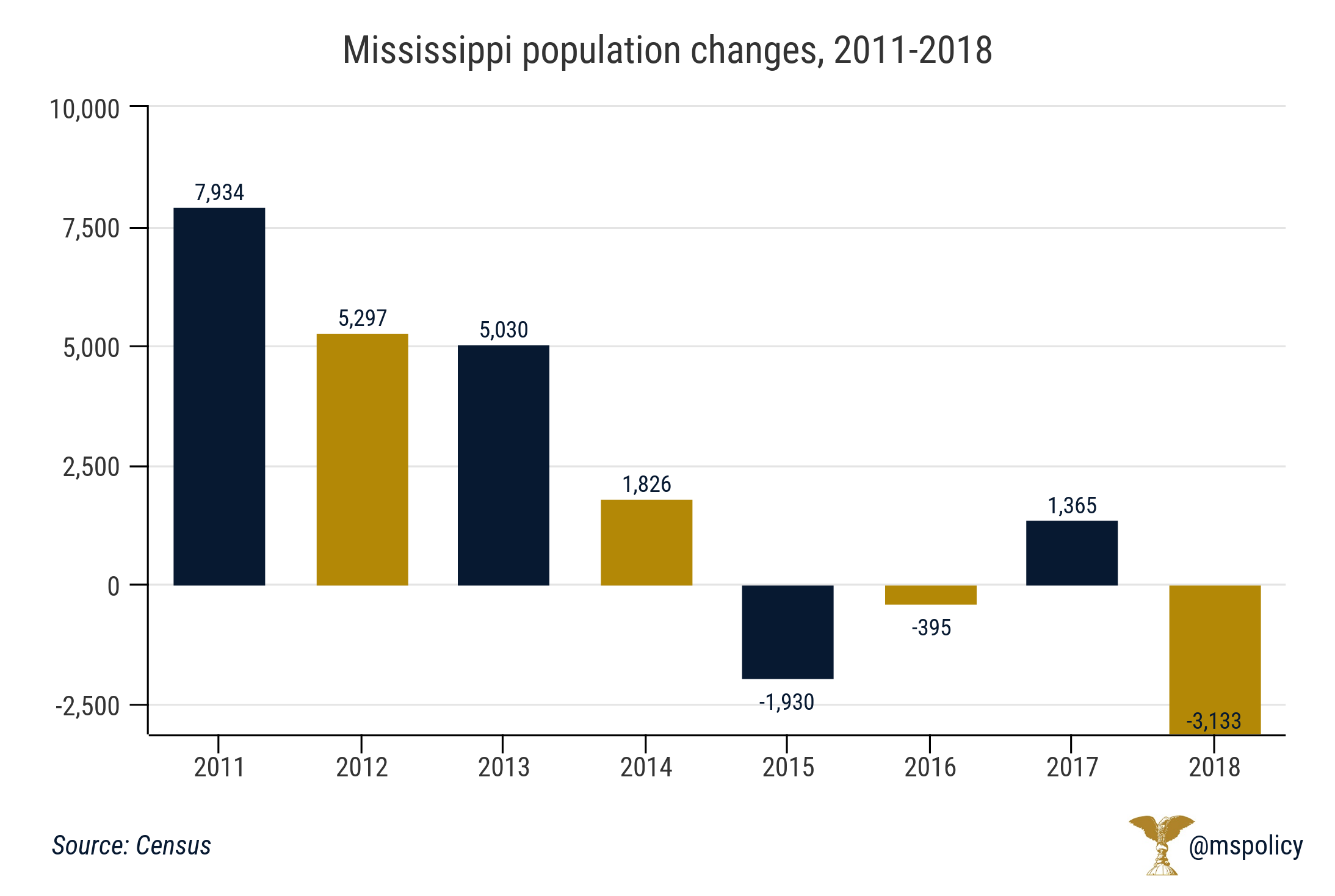

Unfortunately, Mississippi joined New York and Illinois in the group of nine states that lost residents last year. After a small growth last year, Mississippi lost more than 3,000 residents between July 1, 2017 and June 30, 2018. This marks the third time in four years that population has declined.

Nevada, Idaho, Utah, Arizona, Florida, Washington, Colorado, and Texas were the eight fastest growing states, in terms of percentage growth. Each state is known for low taxes and a business-friendly climate. By “business-friendly,” we don’t mean corporate cronyism, monopoly protectionism, and regulatory capture schemes for the companies with the greatest legal and lobbying resources. Instead, we mean states with a predictable and low regulatory and tax hurdle for all shapes and sizes of businesses.

So, do people simply decide they are willing to leave a current high-earning job in a high-tax state to avoid income taxes? Not likely. The truth is taxes aren’t the single driver. Opportunity plays a major role, too. These two factors are incontrovertibly linked.

So, what can Mississippi do to become one of the beneficiaries of American migration? It can focus on fostering a climate that attracts and supports entrepreneurs, whether home-grown or imported, and small business owners. Where entrepreneurs and small businesses thrive, private capital is attracted, in the form of investors, to ideas that improve the lives of citizens.

It has always been true that the pursuit of financial gain, through the private profit and loss system, has been the greatest driver of economic prosperity. When small companies become big companies, the economic benefits to that community are infinitely greater than when government tries to orchestrate them.

Mississippi is a place with gracious people, beautiful surroundings, a temperate climate, and an alluring culture. It’s the kind of place that should thrive when the economy is strong and people are free to flee less hospitable places. Why are we not thriving? Because opportunities have been inadvertently limited by government policies. In short, our preference for federal grants and state-based (public) solutions have thwarted the way a free market economy is designed to work.

We rely on the government for too much. Whether for a grant, a subsidy, an incentive, a contract, or a job, we have far too much public sector involvement in our economy. Indeed, 55 percent of our economy is controlled by the public sector. Such behavior does not lead to sustainable economic growth. In prosperous economies, government plays the important but limited role of protecting liberty, property and enforcing contracts; it does not try to control the allocation of economic resources.

Another significant problem we have, which adversely impacts the opportunities to start and run a small business, is our regulatory environment. Although some progress has been made in the area of new regulatory review, we lack a mechanism to repeal or “sunset” outdated or unnecessary regulations. We need a non-governmental, independent review board with the authority to roll back our excessive regulatory environment, beginning with occupational licensing.

The other driver is our business-related sales and property taxes. In Mississippi, we tax land, buildings, inventory, and equipment at higher rates than all surrounding states. Higher taxes reduce business activity. We make this situation worse when we provide tax exemptions to new companies, shifting even more of the tax burden to existing companies. If we have to offer major tax credits to companies to come here, that proves previous lawmakers created an unfavorable business tax climate. Rather than targeting new companies or industries with tax relief, we should target all companies and industries with a lower business tax climate.

Mississippi can make policy adjustments that maximize our potential to participate more fully in a national economy that is prospering like never before. Every state in the South has benefited from the resulting migration of people escaping high tax states with the exception of Mississippi and Louisiana. If we reduce the cost and burden of government and focus our efforts on creating an economy driven by private entrepreneurs and small business owners, the evidence shows us that economic growth and prosperity will follow.

This column appeared in the Daily Journal on January 20, 2019.

Former Heisman Trophy winning quarterback Tim Tebow was able to play football for his local public school in Florida while being homeschooled.

Tebow, the Heisman winner, two-time national champion, and first round draft pick, made international news most recently when he proposed to Demi-Leigh Nel-Peters, a former Miss Universe.

Florida is one of about three dozen states that allow homeschool students to play sports for their local high school. Some states have enacted this policy through legislation. In other instances, state high school athletic associations have put this policy in place. The Alabama High School Athletic Association recently made such a change.

Though the policies may vary, the intention is similar: just because you are homeschooled does not mean you can’t play sports for your local high school that your taxes are funding.

Every neighboring state permits homeschool students to play high school sports. Mississippi stands out as the only state that does not.

Over the past several years, including this year already, various bills have been introduced in the legislature to make this change. Only once has such a bill made it out of committee and it was killed on the Senate floor thanks in large part to an odd coalition of opponents that included the Home School Legal Defense Association (HSLDA). HSLDA normally take a neutral position on “Tebow bills,” but believed that particular legislation threatened the academic freedom of all homeschoolers.

Homeschoolers in Mississippi enjoy a high level of academic freedom. Something that upsets many people in both parties. In an effort to preserve what homeschoolers have already “won” in Mississippi, it doesn’t look like any changes will be made to the homeschooling code sections any time soon.

At least not until a Tim Tebow comes on the scene in Mississippi.

School district consolidation in Mississippi can offer both efficiency and savings to taxpayers. It is also one of the trickiest, and most sensitive issues, to local residents, and local lawmakers.

Over the past five years, the state legislature has led on the issue with 10 separate consolidation bills impacting 21 different school districts. By 2021, the state will have 13 fewer school districts than in 2014.

The formula behind the consolidation has largely been to merge two, or in some cases three, districts that are in the same county and are both failing, or, at best, struggling. The consolidations have included:

- Consolidating North Bolivar School District and Mound Bayou School District into the North Bolivar Consolidated School District (2014);

- Consolidating Benoit School District, West Bolivar School District, and Shaw School District into the West Bolivar School District (2014);

- Consolidating Sunflower County School District, Drew School District, and Indianola School District into the Sunflower County Consolidated School District (2014);

- Consolidating Oktibbeha County School District and Starkville School District into the Starkville Oktibbeha Consolidated School District (2015);

- Consolidating the Clay County School District and West Point School District into the West Point Consolidated School District (2015);

- Consolidating the Winona School District and the Montgomery County School District into the Winona Montgomery Consolidated School District (2018);

- Consolidating the Durant School District and the Holmes County School District into the Holmes County Consolidated School District (2018);

- Consolidating the Greenwood School District and the Leflore County School District into the Greenwood Leflore School District (2019);

- Dissolving the Lumberton School District into the Lamar County School District (2019);

- Consolidating Chickasaw County School District and Houston School District into the Chickasaw County School District (2021).

Still, school districts in Mississippi serve a lower number of students, on average, than every other state in the Southeast, save for Arkansas. What does that mean? We are spending money on additional salaries, pensions, benefits, buildings, etc. that other states are not. This means less money in the classrooms.

Mississippi’s school districts are inefficient compared to other Southern states

| State | Total enrollment | Total school districts | Students per district |

| Florida | 2,721,459 | 67 | 40,619 |

| North Carolina | 1,443,163 | 115 | 12,549 |

| Virginia | 1,279,544 | 135 | 9,478 |

| Georgia | 1,744,240 | 199 | 8,765 |

| South Carolina | 718,322 | 82 | 8,760 |

| Tennessee | 960,704 | 142 | 6,766 |

| Louisiana | 720,458 | 126 | 5,718 |

| Alabama | 733,951 | 136 | 5,397 |

| West Virginia | 281,439 | 55 | 5,117 |

| Kentucky | 685,176 | 173 | 3,961 |

| Mississippi | 492,279 | 151* | 3,260 |

| Arkansas | 475,782 | 254 | 1,873 |

Source: National Education Association, “Rankings & Estimates 2014-2015”

The average district size among the 12 states was 9,467, almost three times the size of the average district in Mississippi. For Mississippi to be in line with that average, the state would need to see a reduction to 52 school districts, eliminating almost two-thirds of the districts in the state.

Florida is the biggest outlier in this group. Removing the Sunshine State from the mix would drop the average district size to 6,513. Even doing that, Mississippi would still need to drop to 75 districts to be at the average. That is a reduction of almost 50 percent.

Among neighboring states, if school districts in Mississippi were to serve the same number of students as school districts in Alabama, Mississippi would need to experience a reduction to 91 districts. To mirror Louisiana, Mississippi would need a reduction to 86 districts. And to match the same number of students per district as Tennessee, Mississippi would need a reduction to 73 districts. Either of these changes would represent a decrease of 40 to 50 percent of the districts in the state.

Additionally, the districts in Mississippi are largely unbalanced. Half of all public school students in the state attend school in one of just 28 school districts. Yet, 63 districts have less than 2,000 students and educate just 16 percent of students.

There is not a magic size for a district. There are poor performing large districts, starting with Jackson Public Schools, just as there are high-performing small districts. But this inefficient distribution of students, which results in excessive bureaucracy, costs taxpayers money and prevents dollars from making it to the classroom.

While there is overwhelming local pressure to oppose consolidation, the legislature should continue with the process of reducing the number of school districts in Mississippi.

* This data was released before Mississippi began consolidating school districts, but the drop in the number of districts isn’t great enough to change these statistics.

It has often been said that government does not create jobs, it merely creates the environment that encourages, or in some cases, discourages, job growth. When it comes to occupational licensing, the emphasis is on discouraging job growth.

Because of these often burdensome laws, Mississippians are forced to spend time and money to receive permission from the government before they can earn a living.

While licensing was once limited to areas that most believe deserve licensing, such as medical professionals, lawyers, and teachers, this practice has greatly expanded over the past five decades. Today, approximately 19 percent of Mississippians need a license to work. This includes everything from a shampooer, who must receive 1,500 clock hours of education, to a fire alarm installer, who must pay over $1,000 in fees. All totaled, there are 66 low-to-middle income occupations that are licensed in Mississippi.

What is the reasoning behind new licensing? The public argument is generally centered around the belief that we must do this in the name of consumer safety to protect individual citizens. But the reality is often something less altruistic. Mainly, these occupational associations are more interested in building a moat around their industry with the help of government. The harder it is for someone to enter an industry, the less competition and consumer choice the industry incumbents face.

This may artificially raise the wages of industry practitioners by raising the prices of goods and services that require such licenses, but it does so at a cost. Consumer choices are limited and consumer costs are increased. And the added cost is not insignificant. Mississippians pay a hidden tax of more than $800 each year due to onerous occupational licensure requirements, according to a 2016 report from the Heritage Foundation.

In 2018, the Mississippi legislature, with little discussion and few dissenting votes, passed a bill to make it more difficult to become a real estate broker. The proposed law sought to increase the time it would take to become a broker, going from the current one year to three years. Fortunately, Gov. Phil Bryant vetoed the legislation.

Who were the individuals supporting such legislation? Was it the Coalition of Mississippians Against Inexperienced Brokers? A group of citizens negatively impacted by brokers who had just one year of experience? No, it was, naturally, the Realtors Association.

But the bigger problem isn’t just one specific association pushing the legislature to limit competition, it is the cost of all unnecessary and burdensome regulations on Mississippi’s economy.

According to a recent report from the Institute for Justice, Mississippi has lost 13,000 jobs because of occupational licensing and the state has suffered an economic value loss of $37 million. To put that into perspective, just by legislative action to rollback unnecessary licenses, we can create two Nissan plants…without spending a dime of taxpayer dollars.

Instead of relying on government, these are the actions that will encourage and promote economic growth in Mississippi. If that is our goal, we need to trust in the benefits of the free market and a “lighter touch” from government and occupational licensing regimes and we need to return to a belief in individual responsibility.

This can be achieved in a number of ways. For example, voluntary certification offers an avenue for reform. This already occurs in many industries and allows private third-parties to set standards for individuals to voluntary subscribe as one level of quality assurance.

One of the more widely recognized private certifications is the Automotive Service Excellence (ASE) certification for mechanics. You can open a garage tomorrow with – or without – the ASE certification and customers may or may not care.

But that decision is left to the entrepreneur and the customer, not to the government or the industry lobbyist or the board of licensure. We can do this with any number of professions currently licensed by the state. If we really want more jobs and fewer people dependent on government, it starts by creating an environment that encourages work; not one that encourages the creation of hurdles and obstacles.

This column appeared in the Daily Leader on January 4, 2018.

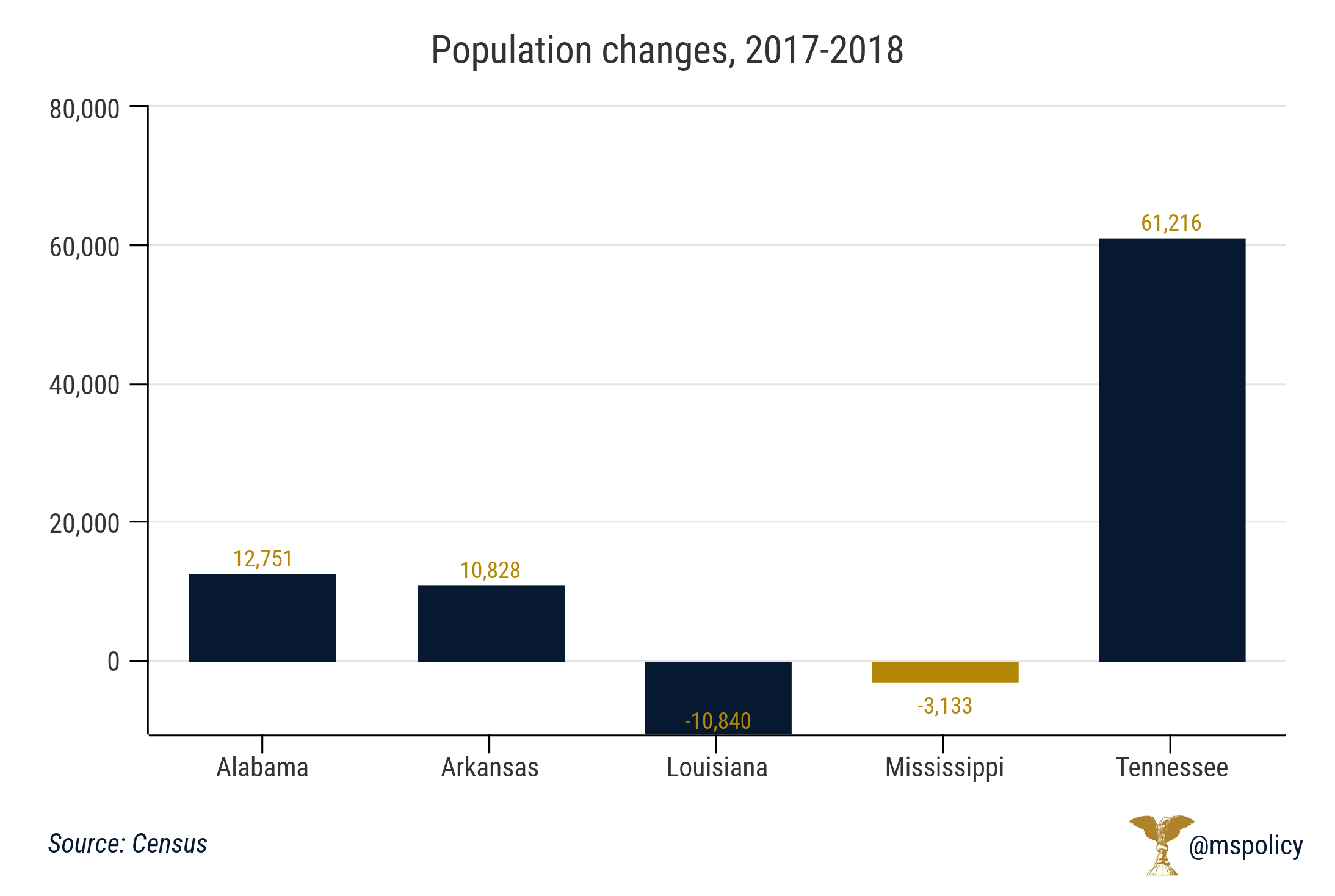

Mississippi and Louisiana both experienced population declines over the previous year, standing out among neighboring states and most of the South.

Louisiana had the fourth highest population loss, in terms of real numbers, at 10,840. Mississippi’s population declined by 3,133. While Mississippi has now seen a population loss in three of the past four years, this was the biggest decline since the official 2010 Census.

The 2018 population estimate is 2,986,530. Mississippi experienced a short population increase of more than 20,000 residents during the first half of the decade, but the population is now down more than 4,000 people since 2014.

Among other neighboring states, over the past year, the population in Alabama increased by 12,751, in Arkansas it increased by 10,828, and it increased by 61,216 in Tennessee.

Tennessee’s population boom isn’t a surprise, or anything new. The state has added more than 400,000 residents since the 2010 Census.

And it’s part of a migration trend. People are leaving progressive income tax states and moving to income tax free states. Over the past year, 339,396 Americans moved to no income tax states, including Tennessee. And 292,947 left progressive income tax states.

Mississippians have among the highest tax burdens

As Census data shows, Mississippi’s tax burden is hurting the state. As a percentage of personal income, Mississippians have a state and local tax revenue rate of 10.57 percent. The national average is 10.08 and the Southeast average is 8.57.

Among neighboring states, Alabama has a rate of 8.23, Arkansas is 9.91, Louisiana is 9.22, and the income-tax free state of Tennessee is 7.76. This means Tennessee runs their government for about 25 percent cheaper than Mississippi. Mississippi is the only state in the Southeast, save for West Virginia, over 10 percent. The Mountaineer state is the highest in the region at 11.23.

Mississippi’s percentage has gone up steadily over the past few years. From 2010-2012, it ranged from 9.84 to 9.88. But this trend has, unfortunately, been going in the wrong direction.

If Mississippi would choose the economic liberty model of limited government and free markets, it would see income growth and poverty reduction.

In simple terms, we’ve advocated for a path to prosperity. That path is built from policies that favor capitalism, free enterprise, robust competition and consumer choice. We do not believe there is another path that leads to durable prosperity, including the path that requires government to involve itself heavily in the orchestration of the economy.

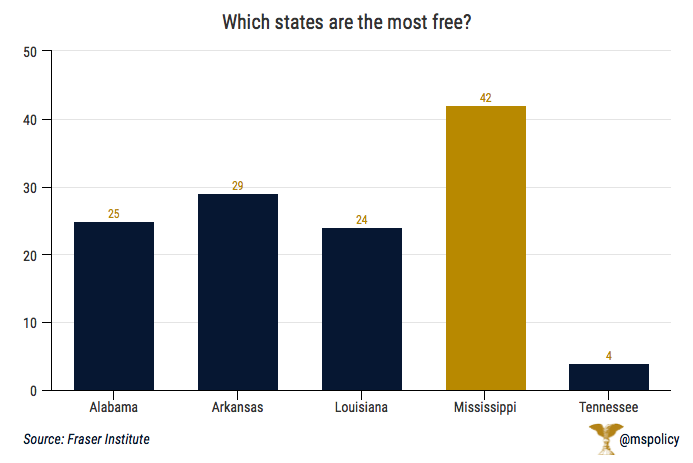

At the end of October, the Fraser Institute, a leading think tank and research institution, published the "Economic Freedom Report for North America." The report measures the degree to which the policies and institutions of states and countries are supportive of economic freedom. The cornerstones of economic freedom are personal choice, voluntary exchange, freedom to enter markets and compete, and security of the person and privately owned property. Forty-two data points are used to construct a summary index and to measure the degree of economic freedom. This report has been published every year since 1986 and is regarded globally as one of the most robust and reliable measurements of economic freedom. Mississippi again ranked in the bottom quartile this year. Among the other states joining Mississippi in that quartile were California, Oregon, Minnesota, New York and Vermont.

Mississippians have very little in common with any of these states. These states are not geographically, politically, historically, or culturally similar to the Magnolia State. In fact, about the only thing Mississippi has in common with these states is its lack of economic freedom.

When we looked at the Fraser Index, which ranked Mississippi at #42 in 2018, we also noted that none of our neighbors were ranked as poorly. In fact, the average ranking for our contiguous neighbor states was #21 and no state ranked higher than #29. If you look to the 11 states making up the Southeast, from Virginia to Texas, the average ranking was 17.

Despite our advocacy for policies based on economic freedom, there remain leaders in Mississippi who seem unconvinced. There remain advocates for more and more reliance on the public sector. Many claim Mississippi is uniquely inoculated from experiencing economic growth and poverty reduction through the free market. Some even claim our lack of economic growth and poverty reduction is irrecoverably tied to our history or our geography. If only there was an example of a state that previously had similar economic freedom scores but embraced economic freedom polices over time and significantly improved the lives of its citizens as a result. If only we had data over the past twenty years than could show us how poverty can be reduced and per capita income can be increased in a state like Mississippi when freedom is the central public policy. Rather than one state, we’ve identified two states than serve as shining examples.

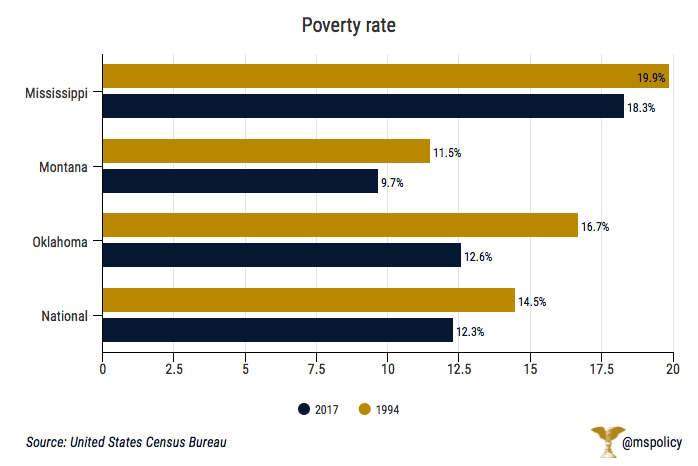

Let’s start by looking at the national poverty rate. In 1994, the rate was 14.5%. Today, the national average is 12.3%, a 15% reduction. In Mississippi in 1994, the poverty rate was 19.9%. Today, the rate is 18.3%, an 8% reduction. In Oklahoma in 1994, the poverty rate was 16.7%. Today, the rate is 12.6%, a 25% reduction. In Montana in 1994, the poverty rate was 11.5%. Today, the rate is 9.7%, a 16% reduction.

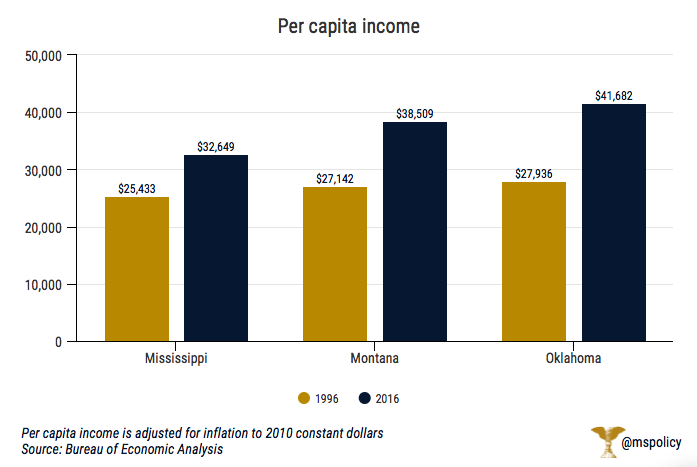

Next, let’s look at per capita income for the three states over a 20-year period. In 1996, the average income in all three states was very similar. In Mississippi, the average income was $25,433 (48thin the nation). Montana had an average income of $27,142 (46th) and Oklahoma $27,936 (45th). Twenty years later, Oklahoma had risen to 28thwith an average income of $41,682. Montana had risen to 38thwith an average income of $38,509. Over that same 20-year period, Mississippi slipped two sports to 50thplace with an average income of $32,649.

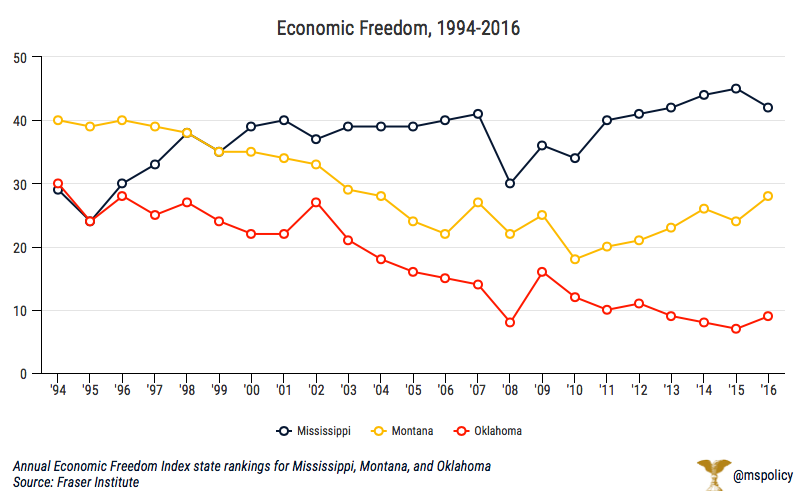

If we go back to the Fraser Institute Economic Freedom Index and plot how each of the three states performed in the same years (1994 to 2016), we see the strong correlation between economic freedom and prosperity. It is stark visual evidence of the power of choosing economic freedom. In 1994, Mississippi was ranked slightly more economically free than Oklahoma and considerably more so than Montana. Over the ensuing 22 years, Mississippi moved steadily away from economic freedom and the results are evident.

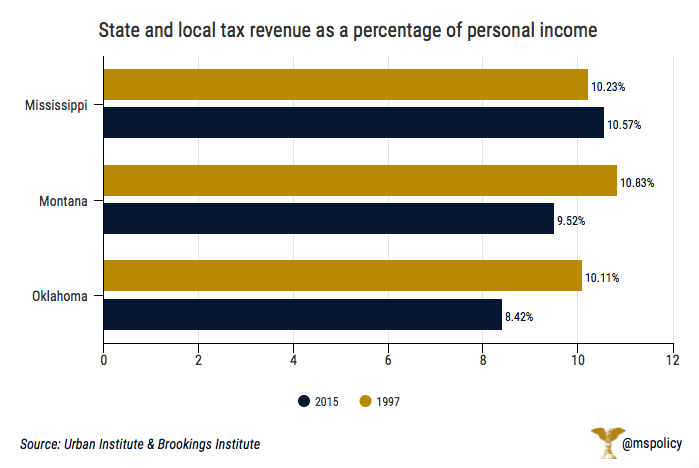

There is another valuable set of data that helps demonstrate the policy point as we compare Mississippi, Oklahoma and Montana. The Tax Policy Center, a joint project of the Urban Center and the Brookings Institute, publishes a report on state and local tax revenue as a percentage of personal income in each state. From 1997 to 2015, the tax burden in Oklahoma fell from 10.11 to 8.42. In Montana, the burden was reduced from 10.83 to 9.52. In Mississippi, the tax burden increased from 10.23 to 10.57. No other state in the Southeast had a burden at or above 10.0. At 10.57, Mississippi finds itself once again in the company of states like California, New York, New Jersey, Minnesota and Illinois.

What is the data and evidence telling us? It is informing us to choose capitalism and free markets. It’s telling us to move away from a “command and control” economic system and start relying more on individual freedom, consumer choice, and private competition. It’s telling us to allocate more resources towards free enterprise and fewer resources towards the political process. If we can start to get Mississippi’s economy growing by adopting policies that prioritize economic liberty, we can experience prosperity.

When states grow, other measures of quality of life are improved. Educational outcomes improve. Crime rates go down. Health measures improve and life expectancy expands. Montana and Oklahoma are real-life examples of how lives can be measurable improved when states make a commitment to economic freedom. They’ve shown us the road map. There is no reason Mississippi can’t take the road to freedom. All it takes is the will and strong leadership to take the first steps.

This column appeared in the Clarion Ledger on December 9, 2018.

Occupational licensing laws force Mississippians to spend time and money to receive permission from the government before they can earn a living.

This is a relatively new phenomenon. In the 1950s, just five percent of the workforce needed a license to legally work. At the time, occupational licensing was largely limited to medical professionals, lawyers, and teachers. However, as we often see when government is involved, license requirements have expanded dramatically.

Today, approximately 19 percent of Mississippians need a license to work. This includes everything from a shampooer, who must receive 1,500 clock hours of education, to a fire alarm installer, who must pay over $1,000 in fees. All totaled, there are 66 low-to-middle income occupations that are licensed in Mississippi.

As new licenses have been added to the books in Mississippi, it is safe to assume that each proponent, usually an occupational licensing board, made the same central argument. We must do this in the name of consumer safety to protect individual citizens. But the reality is often something less altruistic. Mainly, these occupational associations are more interested in building a moat around their industry with the help of government. The harder it is for someone to enter an industry, the less competition and consumer choice the industry incumbents face.

This may artificially raise the wages of industry practitioners by raising the prices of goods and services that require such licenses, but it does so by limiting options and increasing consumer costs. This will often have an outsized impact on low-income Mississippians, who then have to make otherwise unnecessary decisions on what they will or will not purchase.

Just this past year, the Mississippi legislature, with little discussion and few dissenting votes, passed a bill to make it more difficult to become a real estate broker. The proposed law sought to increase the time it would take to become a broker, going from the current one year to three years. Fortunately, Gov. Phil Bryant vetoed the legislation.

Who were the individuals supporting such legislation? Was it the Coalition of Mississippians Against Inexperienced Brokers? A group of citizens negatively impacted by brokers who had just one year of experience? No, it was, naturally, the Realtors Association.

But the bigger problem isn’t just one specific association pushing the legislature to limit competition, it is the cost of all unnecessary and burdensome regulations on Mississippi’s economy.

According to a new report from the Institute for Justice, Mississippi has lost 13,000 jobs because of occupational licensing and the state has suffered an economic value loss of $37 million. To put that into perspective, just by legislative action to rollback unnecessary licenses, we can create two Nissan plants…without spending a dime of taxpayer dollars.

Instead of relying on government, these are the actions that will encourage and promote economic growth in Mississippi. If that is our goal, we need to trust in the benefits of the free market and a “lighter touch” from government and occupational licensing regimes and we need to return to a belief in individual responsibility.

This can be achieved in a number of ways. For example, voluntary certification offers an avenue for reform. This already occurs in many industries and allows private third-parties to set standards for individuals to voluntary subscribe as one level of quality assurance.

One of the more widely recognized private certifications is the Automotive Service Excellence (ASE) certification for mechanics. You can open a garage tomorrow with – or without – the ASE certification and customers may or may not care.

But that decision is left to the entrepreneur and the customer, not to the government or the industry lobbyist or the board of licensure. We can do this with any number of professions currently licensed by the state. If we really want more jobs and fewer people dependent on government, it starts by creating an environment that encourages work; not one that encourages the creation of hurdles and obstacles.

This column appeared in the Madison County Journal on December 6, 2018.