It goes without saying that the post-pandemic world will (at least initially) operate differently than how we are used to. We are essentially in this state of limbo in which many aspects of society have returned to normal, and yet we still see the effects of the pandemic in effect in areas like schools, cities, and public spaces. Economically, the world is placed in a precarious position as stocks continue to fluctuate as fear of the rise of different Covid variants comes into play.

However, this precarious situation has had several impacts on society beyond just the stock market. Due to the fear of some variant rising or more government restrictions being instituted, the percentage of people leaving the workforce for retirement has significantly increased in recent years, and the average retirement age is now 55. The Peterson Institute for International Economics demonstrates numbers that suggest that even those people that are not old enough to retire are less likely to return to in-person employment because doing so may negatively affect their kids' ability to go to school. The net result of this is exactly what America is experiencing at the moment: slow labor-force recovery.

Yet, as Niall Ferguson notes, the U.S. labor market is facing an inflation surge that cannot simply be attributed to fear of Covid exposure. For one, the Biden Administration erred in providing a $1.9 trillion stimulus package earlier in the year when support had already been provided in 2020. The effect of this policy is that people now have excess savings that have provided that extra cushion needed for retirement to become a reality.

However, Ferguson also errs in his assessment that tax credits and cuts in marginal personal income tax rates negatively affect the incentive for people to return to the workforce. The assumption is that those with more money in their pockets will have less of an incentive to work. While this may be true within the context of giving people “free” paychecks in the form of stimulus packages, the effect of tax cuts helps (or at the very least contributes to) economic recovery.

When people receive tax cuts, it does not mean that they can now live with excess money. They still must pay taxes and still have additional expenditures in which to pay. However, the difference is that they now have an incentive to engage in the economy in a much freer manner and that in turn requires them to have jobs to maintain that same level of engagement.

In other words, tax cuts are effectually different from providing stimulus packages. Unfortunately, Ferguson treats them as if they are synonymous. The reality is that the fewer taxes person has to pay, the healthier the economy gets. The labor force is included in that equation. In fact, when Trump cut taxes during the pandemic, it greatly helped the economy. It is when those cuts are removed that recovery becomes stagnate.

Moving forward for the nation and for Mississippi, public policy must be crafted in such a way that encourages people to work and engage in the economy rather than enable them to remain at home, reliant on government money. Ironically, both government interference and an excessive fear of Covid originate from taxpayers giving into a narrative that does not necessarily reflect reality. Relying on the government to return everything to normal is not the answer. Only when people get their hands dirty again and get back to work will the economy eventually return to normal.

In the quest to expand broadband, some have suggested the implementation of government-owned broadband networks as a way to expand internet access. However, before such proposals are adopted, it is important to consider the key problems with government-owned networks.

In the first place, it is important to define what a government-owned network is (GON). GONs are broadband networks that are owned by a state or local government entity. The government entity usually also handles the operation of the network. Advocates of such networks claim that they help fill in the gaps in private sector service, but it is important to test such claims against the actual track record of the networks.

Mississippi has not seen a widespread implementation of GONs. But the effect of potential future implementation should be considered in light of the experiences of other states. According to a study conducted by the Taxpayers’ Protection Alliance, GONs have a consistent track record of costing more than expected to build and maintain.

Such networks consistently do not reach their targeted populations effectively, with many of them only reaching as little as 40 percent of the targeted households. On top of this, many municipalities have incurred millions of dollars in debt that the broadband networks themselves have not been able to pay for. This has led to higher taxes in some places as municipalities try to recoup their losses.

These facts point back to the principle that government entities interfering in the market by shifting taxpayer funds is an ineffective strategy for broadband. Not only are such programs prone to the problems mentioned above, but there is also the systemic issue with the fact that such government intrusion disincentivizes private sector broadband investment.

While a government network pulls from the flow of taxpayer dollars and lacks real competition, private sector companies have to deal with real challenges in a competitive market. In this way, government broadband has an unfair advantage over private-sector broadband companies. This stagnates private sector broadband investment in these areas and makes the broadband infrastructure expansion the exclusive domain of central government planners. Such centralized planning has a consistent track record of faulty projections and an inability to meet the demands of the market.

In order to prevent such failures, Mississippi should do as other states have done and restrict the formation of government-owned networks. Particularly in the wake of new broadband funding coming into the state, leaders should ensure that government entities do not use the funding to create such networks that will put them into debt and crowd out the private sector.

Mississippi needs real solutions to broadband expansion. While municipal broadband advocates often insist that government-owned networks are a pathway to expansion, empirical evidence and free market principles suggest otherwise. Rather than bring false “solutions” to the broadband gap, Mississippi should pursue free-market models that reject the poor track record of government-owned networks.

Mississippi currently stands as one of the cheapest areas to buy a house. In fact, the state ranks 2nd in the United States in cheap housing at a median value of $144,074 per a typical single-family home. However, that home value only increases at a rate of 9.8%, one of the lowest in the nation.

The state government has instituted policies to make the price higher than it should be while keeping the increase in value at a lower rate. One such policy that has affected the prices of housing is the policy towards lumber. Currently, lumber costs are up, and the demand is high. Mississippi currently has plenty of it to make newer houses. The problem is that production cannot keep up with the demand, and it certainly does not help when the Mississippi government places too much of a burden through regulations and bureaucratic control. Mississippi has, in the past, relaxed these regulations in order to ease the burden. It should do so again.

Perhaps the biggest factor in housing costs, however, is the need to build the Mississippi economy. The housing market is often seen as the indicator of a thriving state economy. This is because people are more willing to move into the state in which business is booming. Due to competition, if the economy is thriving and more people want to live in Mississippi, the prices will find its way to an appropriate level. In other words, if Mississippi wants cheap, quality housing, building the economy and letting the market fluctuate naturally is the best way to go.

When considering policy in this context, thinking about the big picture is often the most effective. Edmund Burke often asserts that policy change needs have a specific justification. Simply throwing things at the wall to see what sticks will bring about unforeseen consequences, ones that are often not welcome. If Mississippi sees a thriving market such as the one it sees currently in real estate, it is best to step back and let the natural benefits of the free market take hold. Increasing taxes or implementing regulations will only stifle the process and either plateau or decrease the market's progress.

You know you’ve seriously annoyed progressives when you get singled out for a hit piece in the UK’s Guardian newspaper by one of their New York-based columnists. According to Arwa Mahdawi writing in today’s Guardian, I am a “toxic politician” whom the UK was able to "successfully export."

What was it that prompted Miss Mahdawi, whom I don’t believe I have had the pleasure of meeting, to launch such a highly personal attack on a private citizen in a national newspaper? (Besides Brexit, of course).

Her tirade seems to have been prompted by the fact that I had the temerity to point out that the United States is more prosperous and innovative that Europe.

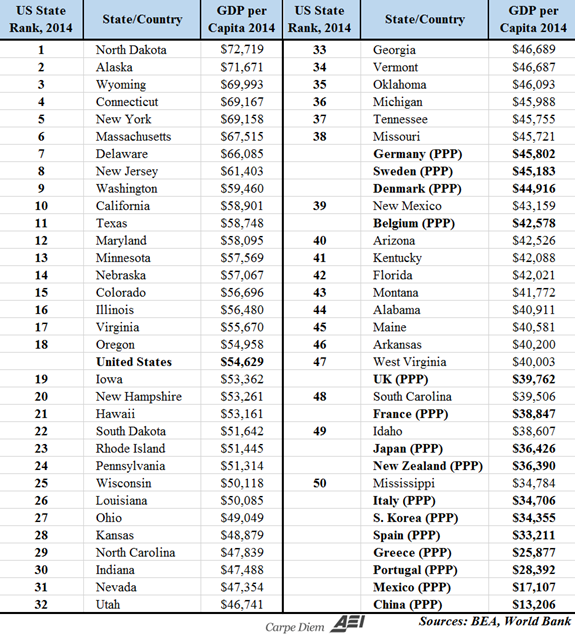

Well let’s consider the facts, for a moment. Here is a table showing how the richest countries in Europe compare the US states in terms of GDP per capita. Germany, Europe’s richest country, ranks below Oklahoma, the 38th richest state in America.

The UK is poorer that Arkansas and West Virginia. Even my own state, Mississippi, ranks above Italy and Spain. If you break the UK down by regions, Mississippi is more prosperous than much of the UK outside of London and the south east.

According to Miss Mahdawi, the US can’t be more successful because she lives in New York, where she “pays way more” for her “mobile phone plan and internet than she would for comparable services in the UK or anywhere in Europe.

Apparently the relative cost of her New York phone bill proves the Europe is better than America. Or something.

Perhaps if Guardian columnists made a little more effort to try to understand what those they write hit pieces on actually thought, they might recognize that free marketers favor more free markets.

But if they did that, then they might be forced to acknowledge that one of the reasons why certain sectors of the US economy have become cartels, without enough consumer choice and competition, is precisely because America is currently led by an administration that seeks to expand the role of government and make America more European. Much easier to make childish insults.

The interesting question to ask is why so many of Europe’s elite feel the need to lash out at anyone that suggests that the American model works better that the European.

In the UK, it is constantly implied the America’s health care system is vastly inferior. Really? Five years after diagnosis, only 56% of English cancer patients survive, compared to 65% of American patients. Poorer Americans in poor states often have healthier outcomes that many in Britain.

But again, these facts are overlooked. Anyone with the temerity to mention them gets vilified (“toxic”). And the many shortcomings in the US system are cited as evidence that nothing good ever happens stateside.

When Europe’s elites talk about America, often what they say – or won’t say – tells us more about them, than anything happening over here. The reality is that by most measures the United States gives ordinary citizens far better life chances than the European Union is able to provide for her people.

Deep down Europe’s elites know this. And they fear that their own citizens know it, too. So they constantly put America down in order to maintain their own status across the pond.

Mississippi’s regulatory code is a massive body of laws with thousands of pages and about 8.9 million words. Unsurprisingly, such a large amount of rules has immense potential to burden Mississippians, inhibit economic growth, and continually increase the size of the government.

While it can be easy to get lost in the specifics of potential reforms, one basic proposal could help to simplify the deregulation process and put the state on a path to better and better reforms. This proposal would require that for every new regulation implemented by the state government, there would have to be two regulations removed.

While this is a seemingly simple proposal, the federal government applied this rule to federal regulations in the Trump Administration starting January of 2017. In turn, the federal government saw a relatively low amount of new regulations in the Trump administration. In January of 2021, President Biden repealed the rule. Thus, although the rule is no longer in effect on the federal level, states still have the opportunity to apply the rule in a state context.

Such prior success on the federal level suggests that an effective approach to deregulation is to recognize that business regulations do not occur in a vacuum. If a company does not have to deal with one specific regulation but faces burdens and obstacles from other regulations, the company may be in just as bad a position as it was before. Thus, while incremental deregulation is effective in some circumstances, the true way to see economic prosperity from deregulation is to implement broader reforms that do not just apply to a specific line of legal code.

Furthermore, while regulatory burdens can substantially affect businesses of all sizes, it is also important to note the particular burden that a strong regulatory environment can have in the Mississippi context. With a large percentage of small businesses, the weight of even one or two additional regulations could be just enough to tip the scales against many such businesses in the state. At the same time, having a regulatory model that proactively removes burdensome regulations could spell the difference between stagnation and growth for businesses across the state.

Using a one-in-two-out model, Mississippi could see a reduction in the total amount of regulatory burdens imposed on Mississippians. While the state has been effective at repealing many of the burdensome regulations, such a policy would help place a statutory cap on the amount of regulations. This is significant so that the state does not find itself incrementally growing the regulatory burden with every passing year of lawmaking.

The legislature should continue to take the lead on removing the regulatory burden in the state. While specific repeals of certain regulations can be an effective method of cutting down red tape, broader deregulation policies could make a real difference in the Magnolia State.

Last September, Toyota, one of the nation’s largest manufacturers of cars with respect to magnitude, announced that the company was going to take a three-week production break. This was due to the company’s slowdown in auto manufacturing across the globe. Workers were allowed to take unpaid leave, work at the plant at various jobs, or take paid time off. This was part of a larger issue that the company is facing as it is cutting global production by 40 percent due to a worldwide shortage of computer chips and vehicle supply parts.

Situations like this often arise when supply chains are not properly handled. California, for example, has become a very weak center for business in this respect. Meanwhile, states such as Texas and Florida have open ports and have invited shipping companies to bring their cargo.

What is the difference? One of the possible reasons is that California policies creates unnecessary barriers to efficiency. For example, California has adopted a law called AB5. This law recategorized truck drivers so that they could not operate as independent contractors working for several companies. In addition, environmental regulations have inhibited the expansion of storage facilities, leading to even more logistical challenges.

It is these kinds of environmental and labor policies that lead to deficiencies in the supply chain. While supplies in Toyota have rebounded and the company plans to make up for lost time, it goes to show how much of an impact a shortage of supplies can have on a given company.

Covid has certainly been a factor in these issues; however, the government cannot use Covid as an excuse for bad policy. On the federal level especially, government has taken prescriptive action for things that do not ultimately help the problem. Anti-contractor legislation, EPA truck emission regulations, and even Biden’s vaccine mandate have all contributed to the nation’s supply chain issues.

Mississippi should seek to counteract these policies as it builds an economy of free-market principles. While they seem justified, government regulations all too often stifle the growth necessary to have a self-sustaining economy. The state legislature should commit to examining the apparent deficiencies in the supply chain system and explore ways to alleviate the burden on private companies that aid the state economy. Giving up government control is the most effective way to manage supply chains.

Agriculture continues to be a token flagship of the Mississippi economy. However, a specific kind of farming continues to grow within the state that has cause for attention. This area of farming is aquaculture, the process of producing farm-raised fish in a water environment.

Over the last couple of years, Mississippi’s aquaculture has grown greatly. According to the most recent data from 2017, the Mississippi aquaculture industry hosts 205 catfish farms, valued at $219.7 million. Mississippi has risen to one of the top producers of aquacultural farming products, so much so that the rest of the country consumes much of what Mississippi produces, bringing in $230.7 million in sales.

This growth is very timely as global demand for seafood and aquacultural products is expected to grow by 70% over the next thirty years thus increasing demand and providing business and jobs. Not only that, but an increase in productivity in aquaculture means an increase in general agricultural business as well. According to a study by the Food and Water Watch, this additional economic benefit comes from the broader agricultural sector producing the food and materials necessary to sustain aquaculture enterprises.

The aquaculture industry is clearly a vital element of the rising Mississippi economy and the state should look to competitive growth as other states expand aquaculture as well. For instance, the New England states have taken advantage of this opportunity and are now generating $150 million annually. The state of Washington also benefits from this, generating $270 million annually.

Expanding this opportunity and taking advantage of this growth would be an excellent area for legislative attention in Mississippi. This is especially true considering that American aquaculture farms have barely scratched the surface of what total demand is necessary to exhaust the industry (America only meets 5 to 7 percent of the current demand for seafood).

Furthermore, when farmers see that one can succeed in aquaculture, new technologies like computer-controlled oxygen monitoring systems have emerged. This enables farmers to monitor and control the oxygen levels in farming ponds. People find something they want to pursue. They find solutions to making that pursuit easier through innovation. That innovation in turn, inspires others to participate. The cycle goes on and on.

This is another perfect opportunity for legislators to make positive changes in Mississippi communities. Fewer regulations and more motivations to participate in markets like these provide opportunities for innovation and growth in the economy. It is a faulty assumption to presume that government needs to compel or even incentivize individuals for growth to occur. The reality is that neither of those things are needed. For growth to occur, as it has in aquaculture, individuals should be able to pursue their interests without fear of undue government interference. If interference is apparent, growth may actually take a downturn. State leaders would do well to further recognize the growth of the aquaculture industry and encourage its free market expansion.

As the world continues to grow in innovation and technology, it continues to shrink in scale. What would be accomplished in weeks or even months a couple of decades ago can sometimes be achieved in a matter of hours. Trade is no exception to this.

Due to innovation in the transportation industry, it is becoming easier and easier for states to benefit from producing and consuming goods from across the globe. Mississippi would do well to continue this trend as it engages in issues of international relevance.

Mississippi has historically benefitted significantly from international trade and investments. For example, in 2013, Mississippi exported $13.2 billion in goods and $2.2 billion in services across 193 countries. As a direct result of this growth, the Mississippi trade sector saw a 154 percent increase in jobs (from 8.6 percent to 21.8 percent). One of the essential elements for this growth came from the existence of free trade agreements which promoted an increase in growth in trade by 469 percent in just ten years (from 2003 to 2013).

Today, while trade is still part of the economy, Mississippi’s export value has slightly dropped. While explaining the reasons behind this decrease are beyond the scope of this article, Mississippi can certainly do more in promoting its engagement in international trade. Today, it ranks 30th in the United States in exports and 28th in the United States in imports.

The Mississippi legislature should keep in mind several key exports that play a role in Mississippi’s international trade scheme: oil & mineral fuels, precision instruments, motor vehicles & parts, industrial machinery, and electrical machinery. These five goods total approximately $8 billion in exported capital and creates and sustains vital parts of the economy.

One way this can be achieved is by promoting Mississippi’s goods across the globe by educating businesses on how to engage in international trade. This can be a daunting task, especially in a small to medium business context. However, the Mississippi Department of Agriculture and Commerce has found success in this area as it has brought $16.7 billion into the state economy by providing support for exporters engaging in international trade. Agriculture is one of the state’s top industries, but imagine if that same engagement occurred on every other major export in the state. Economic growth would certainly be in the future.

Another area that can promote international trade growth is simply decreasing regulation and trade barriers. As mentioned previously, the existence of free trade agreements, minimizing or eliminating the existence of such barriers, played a substantial role in promoting significant growth.

International trade agreements are a little more complicated than a simple “no regulation” principle (it should often operate on a standard of mutual advantage as well). Yet, the idea still stands that governments should encourage companies to engage in trade without penalizing them at same time through high tariffs and regulatory duties.

The greatest element of these free trade agreements is that they encourage competition and innovation -the very things that have placed America in such a strong international trade position to begin with. Mississippi should proactively seek to engage in more international trade and replicate the success the state has seen in the past.

Tesla is now worth over $1 trillion. Not only is Tesla the first car company in the world valued at over $1 trillion, but Tesla is now worth more than twice the combined total of Toyota and Volkswagen.

Not bad for a car company that was only founded in 2003.

Tesla joins a string of companies, including Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, and Alphabet, worth over a $ trillion (Facebook is not far behind, valued at a mere $914bn.).

What is so striking about these firms isn’t just their astronomical value. It’s the fact that they are all relatively new companies. Microsoft and Apple were founded in the mid 1970s. Amazon and Alphabet in the 1990s.

What also stands out is that they are all American.

The largest companies in Europe today – Volkswagen, BP, Shell – were big companies a generation ago. Many of the largest firms in America hardly existed a few decades ago. New, too, is the underlying technology and economic activity on which they are built.

Perhaps any European reflecting on this should ask themselves where their Teslas and Apples are? Or perhaps, more important, ponder what their versions of Bill Gates or Elon Musk are up to? Working in local government, no doubt.

It seems extraordinary that any American politician should want to make their country more European.

What about Japan? I cannot think of a single significant consumer innovation to have come out of Japan since the Sony Walkman. Japan, which in the 1970s and 80s seemed so promising as a center of innovation and technological advance, has stagnated. Perhaps having an economy dominated by zombie companies, weighed down by debt but sustained by cheap credit, isn’t a recipe for success after all.

America has been the epicenter of innovation precisely because Microsoft, then Apple, were able to compete with IBM. Tesla with General Motors. Dozens of start-ups against AT&T. In Japan and Europe, the equivalents of IBM, GMs and AT&T were able to keep out the competition.

For America the lesson is clear; avoid becoming more European or more Japanese. Keep taxes and regulation low. Make sure that however economically important they might be, no big business is able to rig the market through the rule book.