House Bill 1068, sponsored by Rep. Dana Criswell, would require a criminal conviction for property to be forfeited to the state in the case of violations of the state’s Nongame and Endangered Species Conservation Act of 1974.

This law governs the management of endangered species, such as several species of sturgeon, black bears, gopher tortoises, indigo snakes and Mississippi sandhill cranes, among others.

The bill would also require that any proceeds from the sale of any forfeited property be put in the state’s Game and Fish Fund.

It would be the first change to the state’s civil asset forfeiture laws since the sunset of administrative forfeiture in 2018. Administrative forfeiture allowed law enforcement agencies to only have to go to civil court to earn title to seized property if the property owner filed a challenge.

Eighteen states require a criminal conviction (which requires proof beyond a reasonable doubt) to forfeit property to government. North Carolina, New Mexico, and Nebraska have abolished civil forfeiture entirely.

In Mississippi, a law enforcement agency can seize property without an arrest if they can convince a judge that there is probable cause to believe that the property has been used in the commission of a crime or is the product of crime.

The property then goes through a civil procedure with a lower standard of proof than those in criminal courts. If the property owner doesn’t file paperwork with the court to contest the forfeiture, the court almost always rules in favor of the seizing agency. Then the agency receives 80 percent of the proceeds with the prosecuting attorney, either a local district attorney or the Mississippi Bureau of Narcotics, receiving 20 percent.

Going to a system with only criminal forfeiture ensures that both individual and property have the same due process rights and puts the burden on the proof on prosecutors to prove that property is involved with a crime.

MCPP has reviewed this legislation and finds that it is aligned with our principles and therefore should be supported.

Read the bill here.

Track the status of this bill and all bills in our legislative tracker.

While Mississippi has been a leader since 2014 in its efforts to reform the criminal justice system and reduce the state’s prison population, a spate of recent deaths in the state’s prisons have led to calls for more reforms and more spending on corrections.

The Senate Judiciary B Committee held a hearing Tuesday to talk about issues with criminal justice reform and address issues with the state’s prison system, where 15 inmates have died since December 29.

“We didn’t get here overnight and it’s not going to be fixed in one session,” said Sen. Brice Wiggins (R-Pascagoula), the chairman of the Senate Judiciary B Committee.

Wiggins cited a report from the Joint Legislative Committee on Performance Evaluation and Expenditure Review or PEER committee released last fall that detailed how revocations (those on parole being sent back to prison for violations of the conditions of their release) have increased the inmate population after the enactment of the reforms.

According to the same PEER report, an increase in offenders sentenced for drug possession also added to the inmate population.

In January 2014, before the passage of House Bill 585, the state’s inmate population was 22,008. Violent offenders made up 34.7 percent (7,632 inmates) of the prison population.

As of January 2020, the state’s prison population is 19,057 and violent offenders (9,410) represent 49.38 percent of it.

While that’s a big improvement, the numbers have rebounded from 2015, when the prison population dropped 11 percent. Still, Chief Justice Mike Randolph told the Joint Legislative Budget Committee that criminal justice reform has saved taxpayers an estimated $452 million in incarceration costs, primarily due to the drug intervention courts created by HB 585. This bill also created mental health and veteran courts as well.

The passage of HB 387 in 2018 clarified the use of technical violation centers to deal with parolees and the supervised population dealt with by TVCs increased from a low of 190 parolees in January 2018 to nearly 500 by November 2018, according to state data.

Circuit Judge Prentiss Harrell of Hattiesburg is the chairman of the Corrections and Criminal Justice Oversight Task Force. He briefed the Senate Judiciary B Committee on possible problems with the reforms.

One of the main reforms with HB 585 were revisions to the monetary thresholds for certain property crimes that changed many from felonies to misdemeanors and reduced the applicable penalties.

Harrell told the committee that has resulted in the burden for incarceration on these offenders being passed to local communities. He also said the legislature needs to enact new re-entry courts to supervise and help ex-offenders adjust to life outside bars. He said this would reduce the amount of workloads for the state’s probation officers, who often are forced to supervise 300 former offenders.

He’d also like more vocational and technical education opportunities for ex-offenders to reduce recidivism.

State Sen. Angela Hill has sponsored a bill, Senate Bill 2080, that would reduce the workload for probation officers to 100 cases or fewer.

Mississippi Association of Gang Investigators Northern Region vice president and Panola County Sheriff’s Department investigator Jimmy Anthony told the committee that there are unconfirmed rumors of gangs not only infiltrating the state’s prisons, but bribing guards and even having gang members or sympathizers outside the walls hired by the DOC.

He said 41 gangs have been identified operating in the state, including eight outlaw motorcycle clubs.

Anthony told the committee that several national gangs have had thousands of confirmed members behind bars in Mississippi since 2011 (when MAGI data began began), including the Vice Lords (5,542 members in DOC custody), Simon City Royals (2,896), Latin Kings (1,029), Aryan Brotherhood (1,026).

Wiggins authored Senate Bill 2728 last session that would’ve expanded the definition of a gang member and prescribed stiffer penalties for related crimes. It died in committee, as did a similar bill in the House.

He said he wants to bring back similar legislation.

Mississippi already has legislation on the books concerning gangs. The Mississippi Street Gang Act was passed in 1997 and allows the attorney general, district attorneys, or a county attorney to bring a civil case against any gang (defined as three or more persons with an established hierarchy that engages in felonious criminal activity).

Civil forfeiture cases in Mississippi were up in 2019, but the average dollar value of each forfeiture was down.

There were 353 seizures in 2019, according to an analysis of records by the Mississippi Center for Public Policy. That is up from 315 in 2018. The average value in 2019 was $6,073.63, down from last year’s average of $8,708.37.

One reason was the lack of large busts. Only one seizure, $100,715 on April 17 by the Rankin County Sheriff’s Department, was more than $75,000.

In 2018, there were six seizures of more than $100,000, with the biggest being a bust of vape shops by the Mississippi Bureau of Narcotics that netted $644,421.

Only three seizures were $60,000 or more in 2019 after such busts in 2018. The majority of the seizures, 177 were $10,000 or less. In 2018, there were 224 seizures of that amount in the database.

Breaking down the numbers, 118 forfeitures were $2,500 or less in 2019, down from 2018, when 158 met that threshold. Going even lower, 21 were for $500 or less in 2019. That’s down from 2018, when 54 were $500 or less.

As for the property seized, the majority was currency (186), with the average seizure amounting to $5,422. Also seized were 86 weapons (average value of $363.91) and 41 vehicles (average value of $5,091).

Among the unusual items seized included an Xbox One video game console, 16 televisions, an auger (a drilling device), two watches, an Ozark Trail cooler, and 30 ounces of silver bullion bars.

The way the system works is law enforcement officers can seize property if they believe it is connected with a crime. Since the property’s fate is adjudicated in civil rather than criminal court, there is a lower burden of proof for the prosecution.

One part of the law that surprises those unaware is that a property owner doesn’t have to be charged with a crime for his property to be forfeited.

For the property owner to prevent their property being forfeited to law enforcement, which can use 80 percent of the proceeds to bolster their budgets, they must file a lawsuit. That happens precious little, as only 39 property owners contested the forfeiture in court (11.04 percent) in 2019.

In 2018, 30 property owners filed suit to recover their property, or 9.52 percent.

Mississippi legislators are contemplating bringing back an anti-gang bill from last year, but most people don’t realize that Mississippi already has an anti-gang law.

The Mississippi Street Gang Act was passed in 1997 and allows the state Attorney General, district attorneys or a county attorney to bring a civil case against any gang (defined as three or more persons with an established hierarchy that engages in felonious criminal activity).

The existing law also proscribes that anyone convicted a felony committed for, directed by or in association with a criminal street gang would be imprisoned for no less than one year and no more than one half of the maximum imprisonment term for that offense.

Those selling or buying goods or performing services for a gang could face the same punishment as above and an a possible fine of up to $10,000.

Both the House and Senate versions of the gang bill would’ve expanded the definition of a gang to include:

- A common name, slogan, symbol, tattoo or other physical marking.

- Style or color of clothing or hairstyle

- Hand sign or gesture

- Graffiti

Some critics have said this would lead to profiling. State Rep. Bill Kinkade (R-Byhalia) told WLBT that a new bill would need to have the language cleaned up to narrow the definition of a gang.

Both bills would’ve increased the prison term in the original law to five years or less and a fine of no more than $15,000 and no less than $10,000. Both would’ve authorized injunctive relief for people seeking the eviction of gang members on their property and provided for the forfeiture of gang member property.

Senate Bill 2728, authored by state Sen. Brice Wiggins (R-Pascagoula) and it died in committee. The Senate bill differed from its House counterpart in that it would’ve prohibited convicted gang members from parole or any early release program.

State Rep. Fred Shanks (R-Brandon) authored the House version, HB 685 and it also died in committee.

City of Jackson officials are hoping the state will provide $3 million to purchase additional crime prevention surveillance cameras in the city.

The city council passed a motion to request the bond money from the state on Tuesday, according to WLBT.

The city currently has 30 cameras in operation. These were purchased through a $200,000 grant. The Real Time Crime Center allows the city to monitor activity on the streets.

If the city receives the new funding, they would have four to six people monitor cameras around the clock throughout the city. Currently, the cameras are located in south Jackson.

Two drive-by shootings in the final twenty-four hours of 2019 in Jackson. A one and thirteen year old shot in the first drive-by in broad daylight at 10 a.m., no less. Multiple other shootings that occurred throughout New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day. Too many to even count or map rationally on a timeline.

Eighty-three murders in 2019. Eighty-four in 2018.

Something has to give. Law abiding citizens are beyond tired. They are exhausted. Utterly, completely, and totally exhausted. And it feels as if their exhaustion, their desperation, is completely unheard and unappreciated by the powers that be.

When the city addresses this ongoing crisis – if it even bothers to address it, and that is a big question for many – I suspect its comments will primarily focus on lack of economic opportunity. Lack of economic opportunity is one of many factors in the crime equation but, importantly, one over which a local government has very little control, and certainly very little control in the short-term (its importance can also be debated because there are numerous areas around the world with similar poverty rates and access to guns that do not have similar crime rates). It may also deflect towards the nature of domestic disturbances and disturbances among acquaintances and how, in those instances, it is impossible for law enforcement to foresee the dispute and prevent the crime (even though all of these murders and all of our other crimes are not of the domestic or acquaintance disturbance variety).

But I also predict the city will continue to entirely neglect to confront the factors over which the city and county have complete control: the declining numbers of law enforcement to patrol and - perhaps most importantly - the timely prosecution of cases. Patrol staffing levels appear to be at historic lows. Patrols matter. Police presence matters. The problem of timely prosecution is well-known and affects not only law enforcement efforts to control crime, but also, and very importantly, the civil rights of the accused who often sit in jail for unacceptably long periods of time before being brought to trial.

It seems that every lay person in the street knows of these issues and how we are entirely lacking in these areas, yet it is the elephant in the room that is not touched by the powers that be. Why is that?

We can wax philosophically all we want about larger economic issues and their impact on crime – and those can be very real. We can deflect to how law enforcement cannot time-transport itself into the middle of every domestic disturbance to prevent its occurrence, and that is true. But until we control what we can control (such as the numbers of police patrolling and timely prosecuting of cases), economic philosophical musings and deflections to the inability to prevent domestic and acquaintance disturbances ring hollow.

A tripartite approach of swiftness, certainty, and an appropriate degree of severity is a well-known framework for approaching criminal justice issues. Swiftness of prosecution and, if found guilty, punishment; certainty that if found guilty, punishment will follow; and an appropriate degree of severity to fit the crime. We could use more of this here. Currently we have none of it. It is not a panacea, but it is a start.

I am an adamant supporter of criminal justice reform. America’s criminal justice system collectively was indiscriminately and excessively punitive through at least the 1980s and 1990s, and we are now paying high societal and economic costs for decades of irresponsibility and callousness in how we approached criminal justice.

But there is a balance to everything. Our city and county have approached criminal justice from a place so far off the spectrum that it defies categorization. Suburbanites often term it “left” or “liberal,” but that is not accurate. It is not operating from a philosophical perspective; it’s just not functioning. We need to redirect the ship. We can start with the basics: enforcement, and the prosecution of cases.

We are about to have a new district attorney, and that brings great promise for positive change. His predecessor has left him an enormous job of clean-up. Law abiding citizens are literally begging for help.

This column appeared in the Clarion Ledger on January 7, 2020.

The recent rise in violence from Parchman and other prisons has become a leading issue of the day in Mississippi, and even received national attention. Right in time for the start of the 2020 legislative session.

Naturally, one of the first questions you will hear is who, or what, is responsible? Is it the governor; is it the Department of Corrections; is it the low pay of prison guards; or the prisoners themselves? Or, is it something else?

Mississippi has begun to address this question.

In 2014, Mississippi policymakers began to study the issue of criminal justice and explore policy options that would help decrease both crime and incarceration while providing better outcomes for people who encounter the criminal justice system. The passage of House Bill 585 began this process by establishing certainty in sentencing and prioritizing prison bed space for people facing serious offenses.

This helped reduce the state’s prison population by 10 percent and generated nearly $40 million in taxpayer savings. Policymakers have also passed several pieces of legislation since then aimed at removing barriers to re-entry for those leaving the prison system.

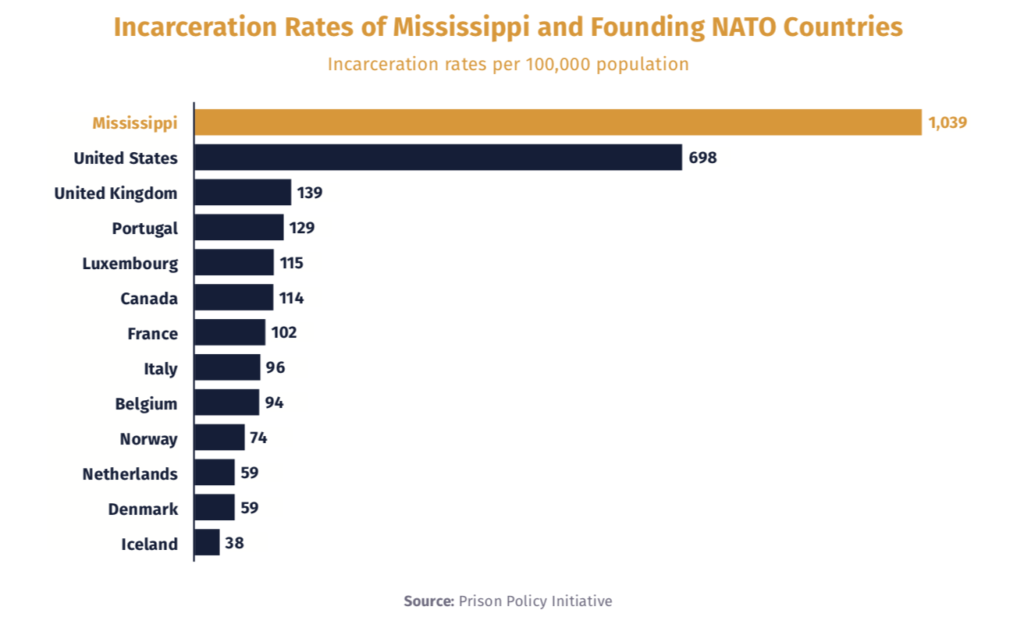

But this isn’t the end of the story. When adjusted for population, Mississippi still incarcerates nearly 50 percent more people than the average of other states and over 10 times as many people as other founding NATO countries like the United Kingdom, Canada, France, and Italy.

From a budgetary perspective, maintaining the state’s prison system accounts for a large portion of Mississippi’s budget — one of the largest discretionary spending items. In 2019, the state sent over $340 million to the Mississippi Department of Corrections. This does not even account for the additional state, local, and county tax dollars spent on police and jails.

Maintaining one of the world’s largest prison systems for a population our size consumes a large portion of the state’s budget. This should lead conservatives to ask, “Are we getting what we pay for?”

It doesn't appear to look that way.

According to the most recent numbers published by the Mississippi Department of Corrections in 2015, over a third of the people released from state prison end up re-incarcerated within three years. This does not even account for people who might be re-arrested. The U.S. Department of Justice estimates that another third of those released will end up being arrested again within three years.

It also appears that our notoriously high incarceration rate has not provided a commensurate decrease in crime. While crime rates in Mississippi are considerably lower than their peak two decades ago, Mississippians are still more likely to be the victim of property crimes than those in other areas of the country.

And the economic impact of the state’s reliance on incarceration is not limited to tax expenditures. Mississippi has the fourth lowest workforce participation rates in the country. This means fewer people are working or looking for work than in most other states. Research shows that one of the main drivers of this lower economic participation is previous involvement with the criminal justice system.

While the state has been lauded for the reforms to this point, the prison population remains stubbornly high, as Mississippi continues to incarcerate more people per capita than all but two other states. The latest numbers show that the state is falling further behind economically, as our workforce participation is growing at a slower pace than most other states. While other states are moving to reform their criminal justice systems to reduce reliance on prison, Mississippi cannot rest on its laurels.

The state can work to significantly reduce the incarcerated population by prioritizing alternatives like drug treatment for crimes driven by addiction, treating drug possession offenses at the local level as a misdemeanor, eliminating the state’s mandatory minimum habitual sentencing structure that imposes long prison sentences on petty offenses, and ending the practice of automatically sending people back to prison for minor violations while on probation or parole.

The state can also fund alternatives to incarceration like intervention courts, community diversions, and community drug treatment that produce system-wide cost savings. We can also paint the full picture by providing the overall cost of each prison sentence to judges before they impose sentences, like in the federal system.

Parchman houses some of the most dangerous criminals in the state (and potentially the world) who have committed heinous crimes and they should not be on the streets. Most can agree with that. However, we have a much larger prison population than the examples we initially think of. And simply having a larger prison population that most hasn’t made us safer. Rather, as the latest news shows, we need to continue to reform our criminal justice system, and reprioritize and refocus its purpose. Simply giving a raise of a few thousand dollars to prison guards won’t do that.

In 2015, the Drug Enforcement Agency raided Miladis Salgado’s home on a false tip that her estranged husband was dealing drugs. In the end, the federal government used civil forfeiture to take $15,000 from Salgado, a large portion of her life savings.

Salgado knew she had done nothing wrong. So she fought back. And won.

But Salgado needed an attorney. She hired an attorney on contingency, and after two long years, the court was about to rule in her favor. That’s when the federal government folded. They admitted there was no evidence of a crime and agreed to return her money.

But in doing so, they refused to pay her attorneys’ fee. Salgado petitioned the judge for the fees, but that request was denied because the government returned her money before a ruling, which would have triggered the government to pay those fees.

That would leave Salgado with about $10,000 of her $15,000 the government took. The other $5,000 would go toward her attorney. Meaning, even though Salgado did nothing wrong and the government illegally took her property, she will still lose $5,000 just for fighting for her property that was rightly hers.

The Institute for Justice brought Salgado’s petition for attorney fees to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Mississippi Justice Institute, along with other public interest law firms, filed an amici curiae (friends of the court) brief in support of Salgado.

“The government spent years trying to take Salgado’s cash,” the amici firms wrote. “It embarked on the all-too-common attrition-by-litigation strategy. Salgado was forced to bear the literal expense of defending against the government’s actions. Even though the government eventually dismissed its case and returned the cash, Salgado wound up with less money than she had before the DEA’s raid.”

The petition revolves around a profound question: When the government dismisses a forfeiture case it has spent years litigating, did the property owner from whom the property was taken ‘substantially prevail’ under federal law?

The idea that the state can keep your property through forfeiture when you have not been convicted of a crime does not sit well with many people. And it doesn’t even do what its supporters like to promote.

The basis of civil asset forfeiture is formed around the idea that your property can be connected to a crime and forfeited to the state, whether you have been convicted of that crime or not. Supporters will often talk about the need to use civil asset forfeiture to deter large drug operations that may cross Interstates 10 or 20. But is that really happening in large numbers?

According to our analysis at Mississippi Center for Public Policy of the civil asset forfeiture database, only 12 percent of seizures have occurred along an interstate route over the past two years and the average seizure is valued at a little over $7,900.

While that is a relatively low number to begin with, there are several outliers that skew the numbers up. Ten of the seizures are of $100,000 or more and the sum of those adds up to a little over $2 million or 47 percent of all seizures. Those 10 seizures have an average value of $204,220, but only represent 2.1 percent of all seizures.

Removing the seizures of $100,000 or more lowers the average to $4,837. The average of the seizures with a total value of less than $50,000 is $4,274 and represents 97 percent of all seizures.

The vast majority of seizures are valued at less than $10,000, representing 84 percent of all seizures. Even smaller were 161 seizures for less than $1,000 or 34 percent of the total.

Cars and weapons remain the most popular items to be seized, but we also had video game consoles, televisions, and a collectible $5 bill.

The state has begun to slowly move in the right direction when it comes to civil asset forfeiture. A few years ago, the state mandated that all forfeitures be posted on a central database. This is the only reason we have a view into Mississippi’s civil asset forfeiture world.

And then in 2018, the legislature let administrative forfeiture die when the law authorizing the program was not renewed. Previously, administrative forfeiture allowed agents of the state to take property valued under $20,000 and forfeit it by merely obtaining a warrant and providing the individual with a notice.

A massive offensive was launched earlier this year to reinstate administrative forfeiture. Fortunately, those efforts were unsuccessful in the legislature.

Still, the bar remains low for forfeiting property. The state is still allowed to seize and keep property through civil forfeiture, a process that requires the state to go before a judge for an adjudication of whether the property should be forfeited, even if the owner does not file suit.

In reality, the cost to recover property, meaning attorney fees and court fees, is often higher than the value of the property forfeited, leaving little incentive to attempt to get your property back.

Seeing the unfairness in such a system, many states have begun to go further in protecting fundamental property and due-process rights. To date, 18 states require a criminal conviction to forfeit most or all types of property. And three states – Nebraska, New Mexico, and North Carolina – have abolished civil forfeiture entirely.

That is the direction in which Mississippi should continue to move. Criminals should not be allowed to keep their ill-gotten gains, but it should require a criminal conviction before the state can keep that property.

Because, save for a few outliers, rather than busting drug kingpins, law enforcement is more likely seizing iPhones, guns, or small amounts of cash.

The truth is that we don’t have to choose between supporting law enforcement or safeguarding civil liberties. We can protect our communities and our Constitutional rights.

This column appeared in the Meridian Star on December 12, 2019.