Criminal justice reform and another bill that would bring clarification to constitutional questions raised regarding actions by cities and counties passed Tuesday out of the Senate Judiciary A Committee.

Tuesday was the deadline for general bills passed by the other chamber to be reported on by committees.

House Bill 1352— also known as the Criminal Justice Reform Act — passed out of the committee with considerable discussion about possible impacts to the state highway funding and other issues.

Mississippi Department of Transportation Executive Director Melinda McGrath and her legal team told the committee that two components of the reform package could put the state in jeopardy of being in non-compliance with federal law. One of those involves the suspension of driver’s licenses for controlled substance violations that were non-moving ones. Another was the expunging of controlled substance violations after a few years in order to allow ex-offenders to obtain commercial driver’s licenses.

McGrath said doing so would put the state at risk for losing millions in federal funding.

Federal law requires at least a six month suspension for any controlled substance violation and changing these requirements could cost the state $36.5 million a year in highway funds for regular driver’s licenses. The part in the bill about CDLs could result in a $14 million funding decrease the first year and $28 million each succeeding year.

State Sen. David Parker (R-Olive Branch) had problems with the legislation over whether it would create loopholes for habitual offenders. He gave the example of an eight-time DUI offender as someone who could use some of the bill’s language as a way to escape prison time. Parker was the lone no vote against the bill.

The Criminal Justice Reform Act is sponsored by state Rep. Jason White (R-West) and would clear obstacles for the formerly incarcerated to find work, prevents driver’s license suspensions for not only non-moving controlled substance violations, but also unpaid legal fees and fines.

The bill would also update drug court laws to allow for additional types of what are known as problem solving courts.

HB 1352 is now headed to the full Senate for a vote. If the bill is amended in the Senate before passage, the differences will have to be settled between the House and Senate in a conference committee.

One bill that didn’t receive a lot of controversy was HB 1268, which would clarify state law regarding constitutional challenges to local ordinances. The bill passed the committee without a single vote against.

With local circuit courts acting as both the appellate body for appeals on specific decisions (such as bid disputes) and the court of original jurisdiction, there’s been a lot of confusion among judges regarding the law that governs challenges of local decisions, which are required within 10 days.

For years, city and county attorneys have used this 10-day requirement on decisions to get new constitutional challenges — which are new lawsuits and not appeals — thrown out of circuit courts.

This law would add language that would prevent application of the 10-day requirement to constitutional challenges, which are new lawsuits and not challenges to decisions.

March 13 is the next deadline for floor action on general bills that originated in the other chamber.

A bill passed by the Mississippi House could impact the rights of the accused in campus sexual assault cases.

The Sexual Assault Response Act requires all of the state’s universities and community colleges to adopt a comprehensive policy on sexual assault that a critic says could hurt the rights of the accused in sexual assault cases.

Joe Cohn, the Legislative and Policy Director for FIRE, said this year’s bill, House Bill 1300— authored by state Rep. Angela Cockerham (D-Magnolia) — is better than the previous two iterations, but still not ideal.

“HB 1300 is not the worst bill we’ve seen on sexual assault, but it’s far from good,” Cohn said. “They’re (the bills) incrementally improving, but they’re still problematic.”

One of those problems was the language in the bill, which labels anyone who brings an accusation as a survivor. He said this signals to people in charge that impartiality isn’t important in the proceedings.

He also had problems with the definition of consent in the bill, which he said means the institution which doesn’t make clear that it has to prove that the sexual activity was non-consensual.

Cohn also said that the bill doesn’t recognize some of the jurisdictional limits of Title IX. He cited a 1999 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education as setting these boundaries.

This decision says that institutions have a duty under Title IX to respond to known acts of sexual harassment or violence either on the institutional grounds or in the programs and activities of the institution.

Cohn said that those who oppose replacing Obama administration era regulations want the jurisdiction of institutions extended off-campus if both people involved are students. This would go far beyond the guidance given by the Davis decision.

He said HB 1300 takes that approach.

There is a provision in the bill that would have any federal guidance or regulation supersede it. Cohn said it’d make more sense to wait for the final regulations, due this summer, before passing a bill.

There have been two previous bills — all authored by Cockerham — which would’ve codified now-superseded guidance provided by a problematic “dear colleague” letter sent to federally-funded universities and colleges by the Obama administration in 2011 concerning Title IX and sexual harassment and assault.

The U.S. Department of Education and its Office for Civil Rights instructed higher education institutions in the letter to use a lower evidence standard to determine guilt and also mandated that accusers would also have the right to appeal a verdict, which meant even baseless allegations could result in a retrial.

Universities and colleges that receive federal funding are required to obey all Title IX regulations or risk having their funding pulled.

For three consecutive years, Cockerham has gotten a bill on campus sexual assault out of the House, but it hasn’t fared as well in the Senate.

In 2017, Cockerham’s first sexual assault bill died in the Senate Judiciary A Committee.

In 2018, a similar bill by Cockerham was doubled-referred (usually a death sentence for a bill) to a pair of Senate committees, Universities and Colleges and Judiciary A, where it also died.

This year, HB 1300 passed by a 115-3 margin on February 13 and has yet to be referred to a committee in the Senate for consideration.

For a third straight session, the Mississippi legislature won’t be addressing a technological gap in the privacy rights of its citizens.

The House Judiciary B Committee — chaired by state Rep. Angela Cockerham (D-Magnolia) — let a bill die on deadline on February 5 that would’ve required a warrant for cell site simulator devices that can represent an invasion of privacy by law enforcement.

House Bill 85 was authored by Rep. Steve Hopkins (R-Southaven) and would’ve provided an exception for the warrant requirement if it was necessary for law enforcement officials to use the cell site simulator device to prevent loss of life or injury.

These devices, also known as IMSI (international mobile subscriber identity) catchers, are used by law enforcement to spoof cell phone towers and trick any cell phone within range of connecting with them.

They were originally developed for use by the military and intelligence agencies such as the NSA, but have now migrated to federal law enforcement agencies such as the FBI and U.S. Department of Homeland Security and now to local law enforcement agencies.

“It goes against all the principles of a free society and the intent of the Founders when the Constitution was written,” Hopkins said. “We have a right to privacy and that’s why there should be laws protecting us from any warrantless wiretap.”

The way these devices work is simple.

Each cell phone has a 15-digit identifier known as an IMSI that they use to communicate with the cellular network. Phones are designed to connect to the strongest tower within range. The IMSI catcher, which is usually mounted in a surveillance vehicle, is designed to crowd out the other towers within range and force the mobile devices within its range (usually about a mile) to connect to it.

Law enforcement can sort through the troves of phones that connect to the cell site simulator and find a particular IMSI that they obtained from a service provider, either voluntarily or by a court order. When law enforcement finds the particular IMSI they are searching for, they can use the device to triangulate its location.

According to a report by the libertarian Cato Institute, these devices can detect where a live mobile phone is within six feet in some cases.

In addition to being able to locate and track the person in possession of a specific phone, these devices are also capable of obtaining their communications content including text messages and calls.

“It was brought to my attention by a resident and I had no idea that law enforcement had the ability to eavesdrop, more or less, without a warrant,” Hopkins said. “Human beings will give into temptation and who’s to say that someone has access to this that they’re not listening in to someone that they may have a vendetta against and use it incorrectly.”

Law enforcement isn’t the only user of the IMSI catchers, as the U.S. Department of Homeland Security admitted last April that it’s aware of unauthorized cell site simulators being used in various parts of Washington, D.C.

These are likely being used by foreign intelligence agencies to eavesdrop on government cellular traffic.

A similar bill last year also authored by Hopkins died in committee.

Here’s what we learned from enacting and defending a modest reform.

A national movement to reform “civil forfeiture” is underway. In many states, current policy allows the government to confiscate property on the grounds that it is connected to a crime — without ever convicting anyone of the crime. In court, a lower burden of proof applies in these civil cases than in criminal cases, even when valuable property such as a vehicle is at stake.

Twenty-nine states have reformed their civil-forfeiture laws since 2014. Fifteen states now require a criminal conviction for most or all forfeiture cases. And the recent skirmish over forfeiture laws here in Mississippi — a “law and order” state by any measure — illustrated that the voting public does not believe there is a contradiction between upholding due process and enforcing the law.

In 2018, the Mississippi legislature allowed the law authorizing one especially troubling type of civil forfeiture, known as “administrative forfeiture,” to sunset. With administrative forfeiture, law-enforcement agencies in Mississippi could take and keep property worth $20,000 or less, so long as they believed it was connected to drug crime, simply by obtaining a warrant and providing a notice to the owner. If the owner did not file suit within 30 days, the property was automatically forfeited to the agency. And given that almost half of all administrative-forfeiture cases involved property worth less than $1,000, it was unrealistic and outrageous to expect property owners to incur court costs and attorney’s fees to bring those cases to court on their own.

In 2019 there was a concerted campaign to bring back the old regime — but it met with pushback led by liberty-minded conservative legislators and my colleagues at the Mississippi Justice Institute, the legal arm of the conservative Mississippi Center for Public Policy.

Keeping administrative forfeiture off the books was a modest reform. It simply ensured that all forfeiture cases go to court for a final adjudication. It did not affect criminal forfeiture, which is when authorities keep property after a criminal conviction. It did not even affect ordinary civil forfeiture, in which agencies keep property after filing suit and proving in a civil court that the property was connected to a drug crime. When asked, most citizens seem to believe that is the least the government should do before it gets to keep your iPhone, your cash, or your truck.

But that did not keep the law’s advocates from painting a doomsday picture of life in Mississippi after the demise of administrative forfeiture. One elected leader declared that drug dealers would move into Mississippi to “get a better deal.” An official for a state police agency took to the airwaves to warn, inaccurately, that drug money would have to be returned to convicted drug dealers after they got out of prison. Officials bluntly advised the public that opponents of changing the law back were “anti–law enforcement” and “pro–drug dealer.” Dozens of police chiefs and sheriffs canvassed the state capitol in full uniform to warn against ending the practice.

The message to legislators was clear: Oppose administrative forfeiture and you oppose law enforcement as a whole. The message to citizens was even more ominous: Choose between your rights and your safety.

Despite all of this, Mississippians made it clear they were overwhelmingly opposed to reinstating administrative forfeiture. Legislators were inundated with calls and emails from concerned citizens. Social media was awash in opposition to reauthorizing the practice. Callers flooded radio stations asking how this could ever have even been the law in the first place. Ultimately, Mississippi legislators listened to the voices of these ordinary citizens. The effort to reauthorize administrative forfeiture did not even receive enough votes to move out of committee.

The lesson for elected leaders in states still weighing forfeiture reforms is this: Don’t fall for false dichotomies. Trust your citizens. They understand that you can support strengthening constitutional rights and also support law enforcement. If you are brave enough to start the conversation, and to stand your ground, you may be surprised how many will stand with you.

This column appeared in National Review on February 13, 2019.

The House and Senate have advanced legislation today that will make it easier for ex-offenders to receive occupational licenses and earn a living.

Introduced by Rep. Mark Baker (R-Brandon), House Bill 1284 would prohibit occupational licensing boards from using rules and policies to create blanket bans that prevent ex-offenders from obtaining employment.

Rep. Baker added an amendment on the floor that will require licensing boards to provide information to PEER on how they are going to change statutory requirements.

A companion bill, Senate Bill 2781, introduced by Sen. John Polk (R-Hattiesburg), has also cleared the Senate.

Under the proposed legislation, licensing authorities would no longer be able to use vague terms like “moral turpitude” or “good character” to deny a license.

Rather, they must use a “clear and convincing standard of proof” in determining whether a criminal conviction is cause to be denied a license. This includes nature and seriousness of the crime, passage of time since the conviction, relationship of the crime to the responsibilities of the occupation, and evidence of rehabilitation on the part of the individual.

An individual may request a determination from the licensing authority on whether their criminal record will be disqualifying. If an individual is denied, the board must state the grounds and reasons for the denial. The individual would then have the right to a hearing to challenge the decision, with the burden of proof on the licensing authority.

If this legislation passes, it would provide hope for ex-offenders who want to turn their lives around and learn a trade so that they can better support themselves and their families.

One of the key bills for criminal justice reform in this session might have a poison pill lurking near the bottom of its text.

Senate Bill 2791, also known as the Reentry and Employability Act, was passed out of the Senate Judiciary A Committee Tuesday, just ahead of the deadline for general bills to pass out of committee.

The Senate Judiciary A Committee — chaired by state Sen. Briggs Hopson (R-Vicksburg) — inserted substitute text that would give those convicted of felony drug offenses the ability to receive public assistance.

On section 27 of the bill, the text says that the state would opt out of 21 U.S. Code Section 862a(a) for all state residents.

This provision in federal law says that any individual convicted of a felony involving the possession, use or distribution of a controlled substance under state or federal law would be ineligible for:

- Temporary aid to needy families (TANF) program which is a monthly cash assistance program for families with children less than 18 years old. Adults participating in the program must be in a work program.

- The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance program, formerly known as the food stamp program, administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The original bill text lacked any mention of 21 USC Section 862a(a) in its original form, which was sponsored by state Sen. Juan Barnett (D-Heidelberg).

States do have the ability to opt out of 21 USC Section 862a(a), which was part of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act passed on August 22, 1996.

SB 2791 would change the way offenders are sanctioned on supervised release for what are known as technical violations that don’t result in an arrest. These violations include failing to show up for an office visit, missing a curfew, lack of employment or testing positive for drug or alcohol. The Department of Corrections would have to impose graduated sanctions before requesting judicial modification or revocation of the offender’s parole.

These sanctions include verbal warnings, increased reporting, increased drug and alcohol testing, mandatory substance abuse treatment and incarceration in a county jail for no more than two days.

The bill would also allow misdemeanor offenders to be released on their own recognizance unless they’re on probation or parole, have other charges pending or the release of the offender would present a danger to the community.

It would also give courts the ability to reduce post-incarceration supervision, which can last up to five years under present law. This would allow probation officers to give more supervision to violent and habitual offenders.

The Mississippi Justice Institute has filed an amicus brief in a case that questions whether courts are required to defer to executive agencies’ legal interpretations of their own regulations.

The brief was filed along with four other constitutional litigation centers from across the country in the case Kisorv. Wilkie. It questions the validity of a legal doctrine known as Auer deference. Under this doctrine, courts are required to defer to agencies’ interpretations of these often ambiguous regulations.

This, despite the fact that interpreting the law is the duty of the courts, not the executive branch.

As a result, federal agencies are incentivized to use vague language when writing their regulations, allowing them to be interpreted on an “as needed” basis. Once challenged in court, the interpretation of the language favors the agency, and receives minimal inquiry.

In the amicus brief, MJI maintains that the legal doctrine of Auer deference gives executive agencies both judicial and legislative powers that the Constitution does not grant them, and argues that any deference afforded to a federal agency must be consistent with the Constitution.

Click here to read the full brief.

President Donald Trump made the recently-passed criminal justice reform one of the big components of his State of the Union speech Tuesday night.

Two of his guests in the Capitol gallery for the speech were Alice Johnson and Matthew Charles, both former offenders helped by his signature of the FIRST Step Act into law in December, one of the biggest bipartisan criminal justice reform initiatives passed in decades.

“This legislation reformed sentencing laws that have wrongly and disproportionately harmed the African American community,” Trump said in his speech. “The FIRST STEP Act gives non-violent offenders the chance to reenter society as productive, law-abiding citizens. Now states across the country are following our lead.

“America is a nation that believes in redemption.”

Thanks to Gov. Phil Bryant and the legislature, Mississippi has been a national leader on the issue since the passage of House Bill 585 in 2014 and has a chance to continue this movement in the right direction with legislation that’s still active in the state legislature.

Senate Bill 2791 and HB 1352 were both approved by the respective judicial committees in their originating chambers before Tuesday’s deadline.

SB 2791 would mandate evidence-based solutions to reduce incarceration and eliminate obstacles for ex-offenders to find work. It would also give courts the ability to reduce post-incarceration supervision, which can last up to five years under present law. This would allow probation officers to give more supervision to violent and habitual offenders.

The Reentry and Employability Act is sponsored by state Sen. Juan Barnett (D-Heidelberg).

State Rep. Jason White (R-West) sponsored the Criminal Justice Reform Act, which would clear obstacles for the formerly incarcerated to find work such as preventing occupational licensing boards from barring licenses to ex-offenders who’ve served their debt to society.

These “good faith clauses” have resulted in two former ex-offenders being denied licenses.

HB 1352 would also end the requirement that an offender’s driver’s license be suspended for a controlled substance violation that wasn’t related to the operation of a motor vehicle.

It would also change the name of drug courts to “intervention” courts and create a fund to help finance programs that would reduce recidivism.

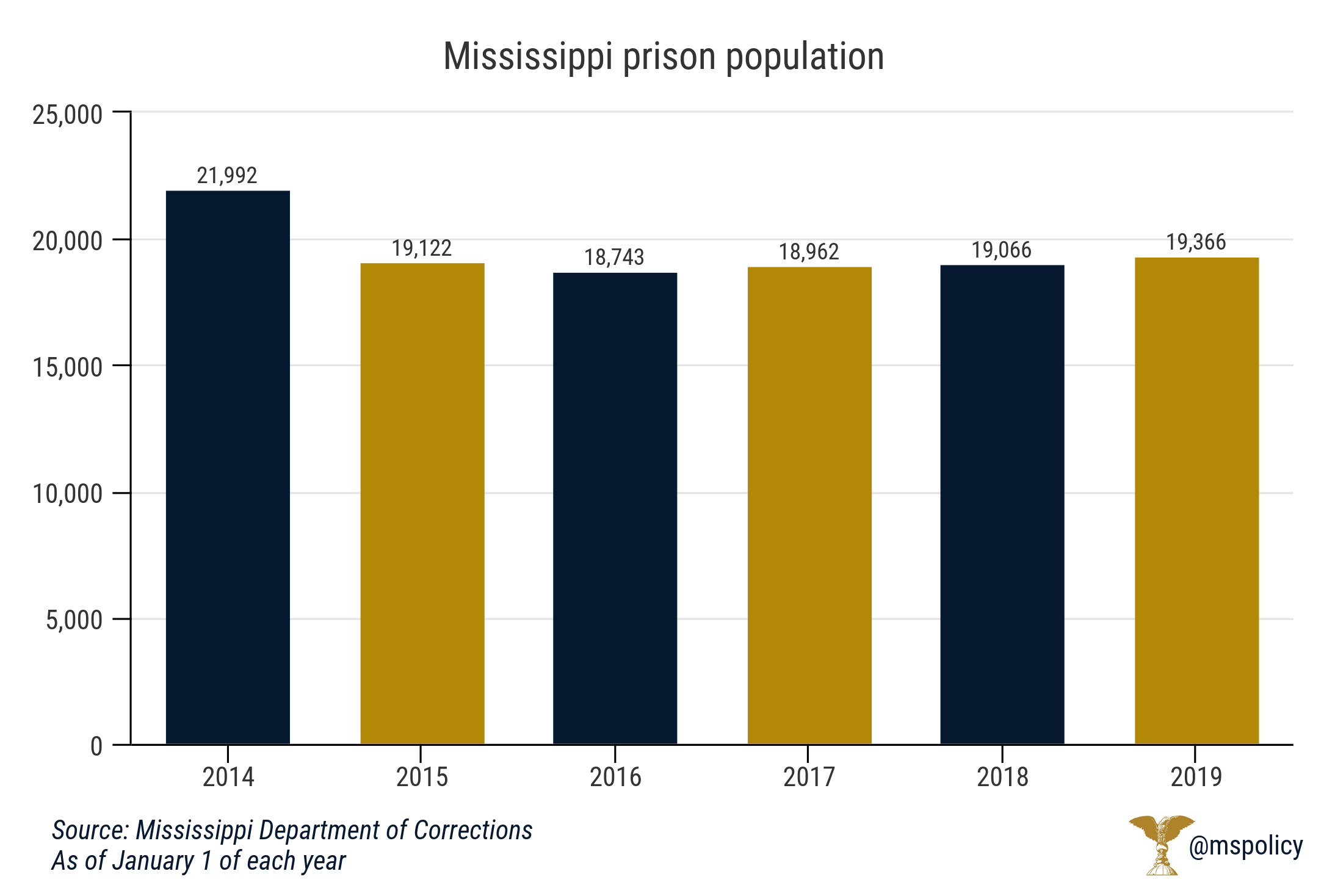

Since the passage of HB 585 in 2014, Mississippi’s prison population has declined from 21,992 inmates on January 1, 2014 to 19,366 on January 1, 2019. That’s a decrease of 11.94 percent.

After bottoming out in 2016, the number of state prisoners has been a slow uptick (3.23 percent) and further reforms could help. Those numbers are still lower (20,988 inmates) than the Pew Trusts predicted for the state’s prison population.

Last year, Gov. Bryant signed another round of criminal justice reforms, HB 387, into law that created a “safety valve” option that allows judges discretion in applying mandatory minimum sentences for repeat offenders and prohibited incarceration due to the inability to pay a fine or fee among other reforms.

These reforms have reduced the number of non-violent offenders in state prisons and given judges more leeway in sentencing when it comes to mandatory minimum sentences for repeat offenders.

Also, the state has outlawed jailing those due to an inability to pay a fine or fee.

A bill that would have reauthorized administrative forfeiture in Mississippi appears to have died on the calendar.

House Bill 1104, which was authored by Rep. Mark Baker (R-Brandon), did not come up in a Judiciary A committee meeting this morning as lawmakers were busy moving legislation before the deadline for committees to report on legislation.

Baker told WLBT’s Courtney Ann Jackson that there wasn’t support for the bill in the Republican caucus.

All bills that do not make it out of committee today are dead for 2019, unless the governor calls a special session or supporters find a way to amend a bill that is still alive.

Last session, the legislature let administrative forfeiture die when the law authorizing the program was not renewed. Previously, administrative forfeiture allowed agents of the state to take property valued under $20,000 and forfeit it by merely obtaining a warrant and providing the individual with a notice. In order to get the property back, an individual was required to file a petition in court within 30 days and incur legal fees in order to contest the forfeiture and recover such assets.

For these reasons, administrative forfeiture was viewed as a particularly pernicious policy that placed lower-income property owners in the difficult situation of deciding whether to pay a legal bill that could exceed the value of the forfeited assets in order to get their property back if they were not involved in a drug-related crime.

The state is still allowed to seize and keep property through civil forfeiture, a process that requires the state to go before a judge for an adjudication of whether the property should be forfeited, even if the owner does not file suit. Additionally, this has no impact on the state’s ability to seize property through criminal forfeiture.