It would take the average person more than 13 weeks to wade through the 9.3 million words and 117,558 restrictions in Mississippi’s regulatory code.

This is according to an analysis from James Broughel and Jonathan Nelson at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. They have taken a deep dive into the regulatory burdens of each state, including Mississippi.

What do regulations look like in Mississippi? In terms of government subdivisions, the biggest regulator, by far, is the Department of Health, with more than 20,000 regulations. That is followed by the Department of Human Services with over 12,000 regulations, and 10,000 plus regulations for state boards, commissions, and examiners. The most regulated industries were ambulatory healthcare services, administrative and support services, and mining (except oil and gas).

Overall, Mississippi was middle of the pack when it came to administrative regulations. It would take 31 weeks to read all 22.5 million words in the New York Codes, Rules and Regulations, which has 307,636 restrictions. But regardless of the state, there is generally one consistent – the number of regulations are only increasing.

Regulatory growth has a detrimental effect on economic growth. We now have a history of empirical data on the relationship between regulations and economic growth. A 2013 study in the Journal of Economic Growth estimates that federal regulations have slowed the U.S. growth rate by 2 percentage points a year, going back to 1949. A recent study by the Mercatus Center estimates that federal regulations have slowed growth by 0.8 percent since 1980. If we had imposed a cap on regulations in 1980, the economy would be $4 trillion larger, or about $13,000 per person. Real numbers, and real money, indeed.

On the international side, researchers at the World Bank have estimated that countries with a lighter regulatory touch grow 2.3 percentage points faster than countries with the most burdensome regulations. And yet another study, this published by the Quarterly Journal of Economics, found that heavy regulation leads to more corruption, larger unofficial economies, and less competition, with no improvement in public or private goods.

A prescription for lowering the regulatory burden on a state is the one-in-two-out rule, or a regulatory cap. In 2017, one of President Donald Trump’s first executive orders was to require at least two prior regulations to be identified for elimination for every new regulation issued. This is badly needed. We have gone from 400,000 federal regulations in 1970 to over 1.1 million today.

Many years ago, British Columbia took on a similar mission. And in less than two decades, their regulatory requirements have decreased by 48 percent. The result has been an economic revival for the Canadian province.

And one state has the unique ability to rewrite their book on regulations. This year, the state of Idaho essentially repealed their entire state code book when the legislature adjourned without renewing the regulations, something they are required to do each session because the state has an automatic sunset provision.

Now, the governor of Idaho is tasked with implementing an emergency regulation on any rule that should remain. The legislature will consider them next year. There are certainly needed regulations, just as there are unnecessary or outdated regulations that serve little purpose. But, the difference is, the burden on regulations now switches from the governor or legislature needing to justify why a regulation should to be removed to justifying why we need to keep a regulation.

Whether it’s a sunset provision or one-in-two-out policy, Mississippi should move in the direction toward a smaller regulatory state with more freedom. And if a regulation is truly important to our well-being, let the regulators prove why. In a state in need of economic growth, let’s find a way to remove unnecessary barriers and inhibitors.

This column appeared in the Starkville Daily News on June 6, 2019.

Mississippi is the nation’s most dependent state on federal funds and, if Louisiana is any guide, the addiction to federal money would only worsen if Medicaid was expanded.

Federal funds for Louisiana increased 41.63 percent between 2016, before Medicaid was expanded, and 2019.

In Mississippi’s newest $21 billion budget which goes into effect on July 1, 44.5 percent of revenue comes from federal sources. Only 27.26 percent came from the state general fund (state taxes such as income and sales) and 25.32 percent sourced from other funds, such as user fees.

Medicaid ($4.94 billion in federal matching funds) represented 52.63 percent of all federal funds appropriated for Mississippi.

Medicaid covers 674,544 enrollees in Mississippi or about 22.6 percent of the state’s population.

Adding other social welfare programs, such as Temporary Aid to Needy Families (TANF) and Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP), bring that social welfare’s share to 68.57 percent of federal outlays for the state.

The percentage has changed little in the past four years, with an average of 44.37 percent of the state’s revenues coming from federal sources. Also not budging was the percentage represented by social welfare spending, which averaged 67.72 percent of federal money appropriated for Mississippi.

The Tax Foundation ranked Mississippi as the state most dependent on federal funds as a percentage of its revenues, with Louisiana second.

Expanding Medicaid as Louisiana did in 2016 would only worsen this dependence compared with the rest of the nation.

So far, 36 states have expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, which is more commonly known as Obamacare. The ACA dictates that the federal government cover 90 percent of the costs for expanding eligibility to all individuals earning less than 138 percent of the federal poverty level.

In Republican Gov. Bobby Jindal’s final $28.2 billion budget in fiscal 2016, the Pelican State received 34.98 percent of its budget from federal funds. More than 62 percent of that was for Medicaid ($5.87 billion in federal funds alone).

By 2019, the state’s budget ballooned to $33.99 billion under Democrat Gov. John Bel Edwards, with 41.53 percent of all revenue coming from federal sources.

Medicaid spending ($9.81 billion in federal match) accounted for 69.51 percent of all federal revenue appropriated for Louisiana.

According to the Louisiana Department of Health, 465,871 adults had enrolled in Medicaid expansion as of May 8, 2019, which was a decrease from 505,503 as of April. The state could have as many as 1.7 million people or 37 percent of the state’s population enrolled in Medicaid.

According to a report by the Louisiana-based Pelican Institute, state officials expected 306,000 new enrollees when it expanded Medicaid eligibility.

A non-profit organization that deals with healthcare and education programs in the Delta is in the process of paying back $1 million from a federal grant to taxpayers for spending disallowed by federal rules.

According to a 2015 decision by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Delta Health Alliance — a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization that receives most of its money from taxpayers in the form of federal and state grants — had to pay back $1 million out of more than $34 million in grants for healthcare and educational programs in the impoverished Delta region.

According to the organization’s 2017 audit, the organization will pay back the $1 million over a period of 10 years, interest free, with payments of $100,000 paid annually in a deal it reached with the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration in 2017.

Some of these costs disallowed in the HHS decision included new furniture for the DHA’s offices in Ridgeland and costs related to a gala at the B.B. King Museum to celebrate the one-year anniversary of one of the programs covered under the grant.

The Health Resources and Services Administration, which is an agency of the HHS, determined that the alliance spent more than $1 million on disallowable items in 2014. The DHA appealed the determination before the Departmental Appeals Board, which issued the final decision on March 12, 2015.

When a federal agency supplies a grant, the money comes with restrictions on how it could be spent. The U.S. HHS disallowed some of the spending by the DHA from 2009 to 2011 under the grant. Some of these included:

- $152,474 in payments made for an information technology consulting contract with the Coker Group that included $31,000 and $33,900 for a chief information officer consultant, travel costs plus the costs of renting an apartment along with furniture and utility costs.

- $79,584 for payments to the Keplere Institute for a summer program that provided workforce training in pharmacy technology unrelated to the grant’s purpose.

- $77,998 for direct and indirect costs for charges made for travel and other expenses to the DHA credit card.

- $69,965 for a contract with the Compass Group, which was hired to develop fundraising strategies for the organization for when the grants expired.

- $48,785 in direct and indirect costs for travel and telephone allowances by DHA employees.

- $45,727 in direct and indirect costs for furniture for DHA’s Ridgeland office.

- $42,182 for DCG Inc. for policy development, statistical analysis and consulting services that benefitted other work by the DHA unrelated to the grant.

- $27,575 for payments to external reviewers hired by DHA to assist in evaluating proposals for projects funded by the grant.

- $17,768 for promotional items, sponsorships and other costs.

- $11,232 in direct and indirect costs for event costs that included the rental of space and refreshments for a celebration at the B.B. King Museum to celebrate the one-year anniversary of the Indianola Promise Community, one of the programs covered by the grant.

According to the audit, 70.84 of the DHA’s 33.12 percent of the DHA’s funding in 2017 came from the U.S. Department of Education and 37.72 percent came from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The organization has received $10.6 million over the past four years from state taxpayers for a technology-based program to help providers reduce preterm births and conditions that can lead to type II diabetes among the Medicaid population in a 10-county area in the Delta.

The legislature appropriated $4,161,095 in the recent session for the project in Medicaid Division’s appropriation bill that was signed into law by Gov. Phil Bryant and goes into effect on July 1.

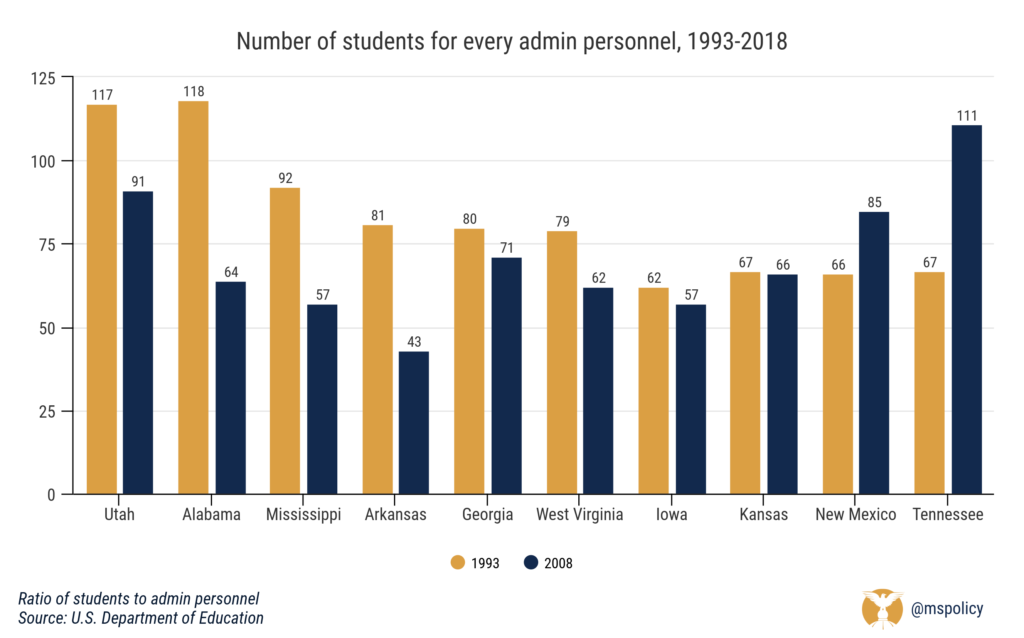

Mississippi was once better than the national average when it comes to students per each administrative employee in public K-12 schools, but now lags behind the national average.

According to an analysis of data from the National Center for Educational Statistics, the state had more students per administrative staffer (92:1) than the national average, 75:1, in 1993.

By 2018, the U.S. average was down to 63 students per administrative employee and Mississippi had fallen below that number at 57:1.

Administrative personnel are defined as school administrators (principals and assistant principals), district administrators and administrative support staff (both at the individual school and district levels).

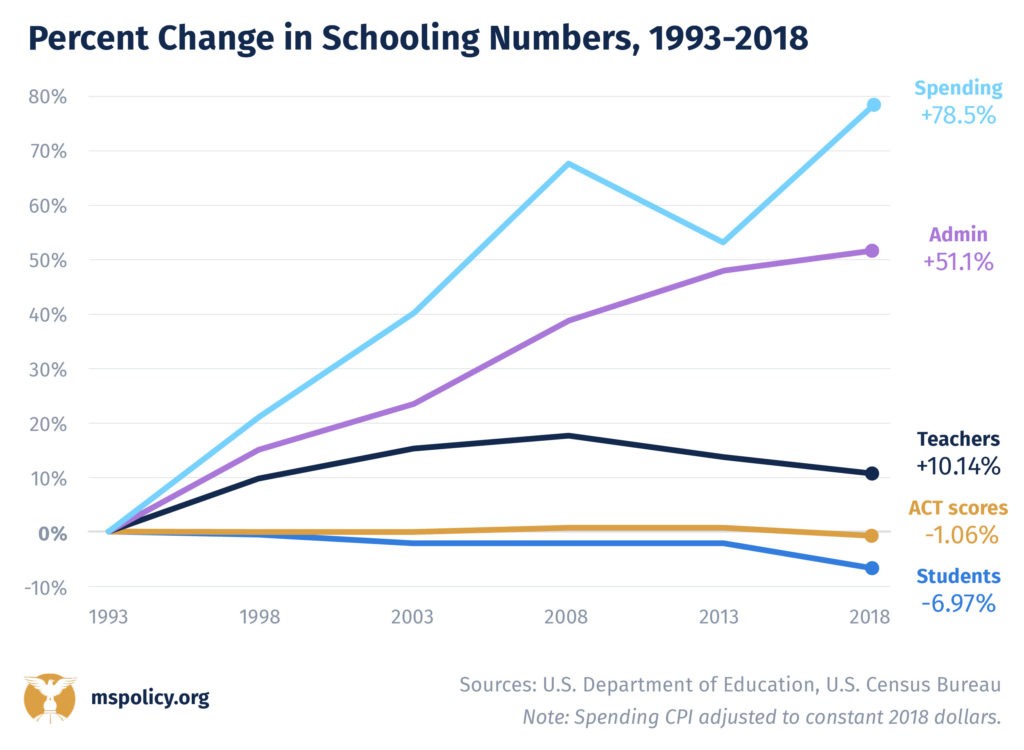

The number of administrative personnel in Mississippi public schools increased by 51.1 percent from 1993 to 2018 while the inflation-adjusted spending on K-12 increased by 78.54 percent during the same span, according to data from the NCES.

According to the fiscal 2020 budget summary, $9.381 billion of the state’s $21.08 billion budget (44 percent) is from federal funds.

A useful exercise is to compare the growth of K-12 administrative staff in the Magnolia State with states with similar populations, with West Virginia included because of a similar rate of poverty. These states include:

| State | Population |

| Utah | 3,161,105 |

| Iowa | 3,156,145 |

| Arkansas | 3,013,825 |

| Mississippi | 2,986,530 |

| Kansas | 2,911,505 |

| New Mexico | 2,095,428 |

| West Virginia | 1,805,832 |

In 1993, Mississippi (92:1) had one of the nation’s smaller K-12 administrative states. This was better than states with far larger populations, including Florida (65 students per administrative employee), Tennessee (67:1) and Georgia (80:1). Only Alabama regionally (118 students per administrator) was better than Mississippi.

Arkansas was next best, with 81 students per staffer. Iowa was the worst, with 62 students per administrative staffer.

Fast forward to 2018 and the Mississippi’s growing K-12 administrative state (57:1) put the state near the back of the pack, worse than all but Arkansas and tied with Iowa. The Natural State had 43 students per every administrative staffer.

West Virginia had 62 students per administrative employee, while Alabama had 64 per staffer. Georgia (71 students per staffer) and Tennessee (111 students per administrator) were two of the best in the Southeast.

Florida was the worst regionally, with 40 students per administrator.

In 1993, K-12 spending from state, federal and local sources in Mississippi added up to $2,737,277,644, adjusted for inflation.

By 2018, that figure ballooned to $4,886,998,652, despite the number of students shrinking from 505,907 in 1993 to 470,668 in 2018.

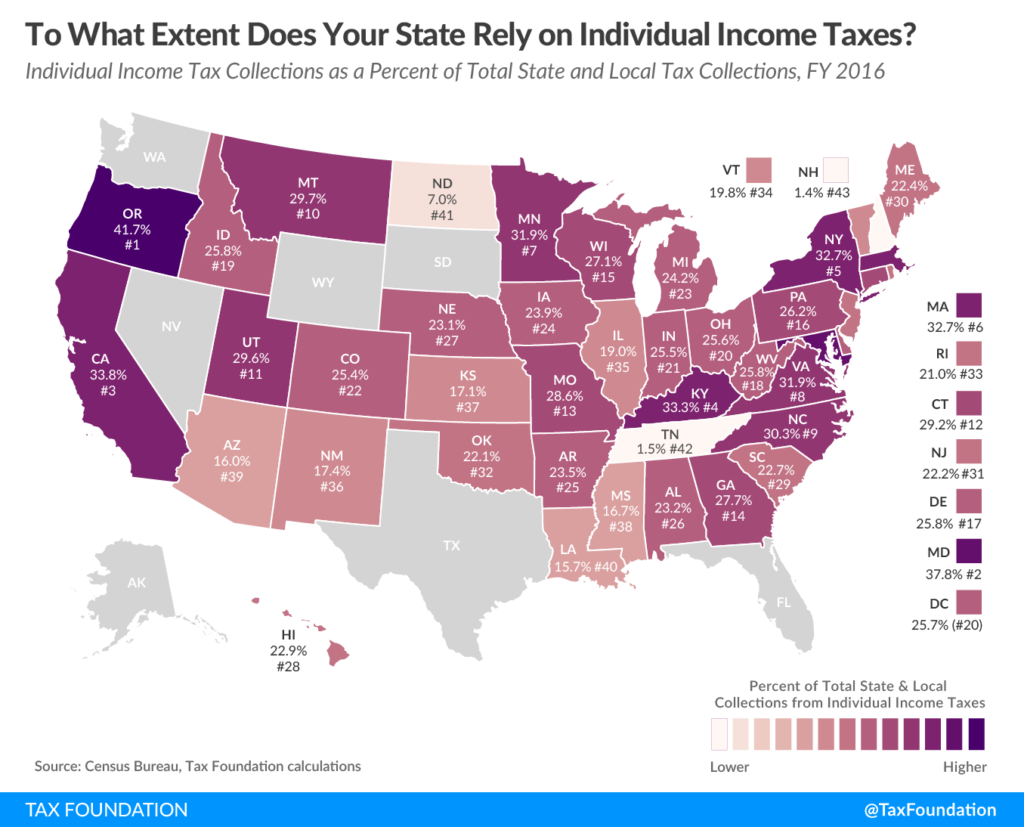

Individual income taxes account for 17 percent of Mississippi’s state and local tax collections.

That is one of the lowest percentages in the country among state’s that collect income taxes. According to the Tax Foundation, Mississippi came in at 38th lowest, behind just Arizona, Louisiana, and North Dakota.

Arkansas and Alabama were both middle-of-the-pack at 23.5 percent and 23.2 percent, respectively.

Oregon and Maryland relied most heavily on individual income taxes, at 41.7 and 37.8 percent, respectively. In Oregon’s defense, they do not charge a sales tax, contributing to the heavy reliance on income taxes.

Still, there is a better way to levy taxes. Mississippi should follow the model of neighboring Tennessee, which does not collect income taxes. (Tennessee does have a tax on investment income, known as the “Hall Tax,” but that will be fully repealed by 2021.)

Because how a state chooses to collect taxes has far-reaching implications. Income taxes tend to be more harmful to economic growth than sales taxes or property taxes. After all, sales and property taxes tax people on what they spend. Income taxes tax you on what you earn, either through labor or savings. Income taxes are also a less stable source of tax revenue, as individuals are more likely to experience more volatility with income than consumption.

Mississippi has begun the process of moving to a flat-income tax, with the phase out of the three percent tax bracket over several years. That is a good start. We have also debated legislation that would make recent graduates eligible to receive a rebate up to the full amount of their individual state income tax liability after they work in the state for five years. Essentially, Mississippi would be an income tax free state for a few years after graduation in an attempt to attract young talent to the Magnolia State.

That is a good thing. We should just expand it to everyone. By following the lead of high-growth, low-tax states in the Southeast that have lower taxes, lighter licensure and regulatory burdens, and a smaller government, we will be able to offer opportunities for people regardless of their age or their industry.

The executive director of Mississippi’s Medicaid program recommended to legislators that they should end state funding for a demonstration project run by the Delta Health Alliance.

Drew Synder, the executive director of the state Division of Medicaid, said in a December 28 letter to the legislature that that he’d “remain unable to endorse the (Mississippi Delta Medicaid Population Health Demonstration) project in its existing form as a cost-effective use of taxpayer dollars” despite speaking favorably about some of the people involved and the overall concept.

The Delta Health Alliance is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization that implements healthcare and education programs in the impoverished Delta region. It receives most of its money from taxpayers in the form of federal and state grants.

The project is supposed to use information technology to help providers reduce preterm births and conditions that can lead to type II diabetes among the Medicaid population in a 10-county area in the Delta.

Legislators ignored Synder’s advice and appropriated $4,161,095 for the project in Medicaid Division’s appropriation bill that was signed into law by Gov. Phil Bryant and goes into effect on July 1.

That’s on top of more than $10.6 million that’s been appropriated over the last four years.

- The appropriation bill for 2015 lists the demonstration project as one to receive state funds, but doesn’t specify how much will be spent on it.

- In 2016, the appropriation bill also didn’t specify the amount directed to the project, but also included $500,000 for a “patient-centered medical model home” in Leland, where the DHA is headquartered. The DHA’s tax form lists $1,376,231 in spending on the program for that year.

- The 2017 appropriation bill didn’t specify the amount for the project and included a $500,000 appropriation for the medical model home in Leland.

- The 2018 appropriations bill had $3,945,889 allocated to the project, with $2,879,051 to continue the existing program and $1,066,838 for the purpose of drawing matching federal funds. The bill also included another $500,000 for the medical model home.

According to an examination of records on the secretary of state’s website and DHA’s own tax forms, the organization hasn’t spent any money on lobbying the Legislature. State Rep. Willie Bailey (D-Greenville) is on the DHA board of directors.

According to the letter, the project has served only a few hundred beneficiaries and could be led by the managed care companies at a 76 percent federal match. He also said the project partially overlaps with an existing personal healthcare monitoring report program at the state Department of Health that’s funded already by DOM.

The letter also says that the project gives $80,000 per month to a health care information technology subcontractor for a predictive algorithm tool that hasn’t been utilized to find high-risk pregnant women for the study.

The DHA was created in 2001 as a collaboration by the five public universities led by former U.S. Sen. Thad Cochran to meet the healthcare and educational needs of the 18 counties in the Mississippi Delta region and funded by earmarks from the former chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee.

In 2017, DHA had $18,806,915 in revenue, primarily from federal and state funds and the group spent $19,340,337 for a deficit of $533,422. Among the $14,275,706 in government grants received by the organization in 2017 include:

- $5,642,945 in various grants from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- $3,284,675 from the U.S. Department of Education for the Indianola Promise Community.

- $3,114,998 from the Sunflower Childcare Coalition for early Headstart.

Program services accounted for $14,391,625 of those expenditures.

A non-profit organization that receives most of its budget from federal grants and implements healthcare and education programs in the impoverished Delta region has a CEO whose salary and benefits has exceeded $350,000 for the past seven years.

The Delta Health Alliance — a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization based in Leland — is led by Karen Matthews, whose staff had 10 employees earning $100,000 or more per year in 2017.

The DHA was created in 2001 as a collaboration by the five public universities led by former U.S. Sen. Thad Cochran to meet the healthcare and educational needs of the 18 counties in the Mississippi Delta region and funded by earmarks from the former chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee.

In 2017, DHA had $18,806,915 in revenue, primarily from federal and state funds and the group spent $19,340,337 for a deficit of $533,422. Among the $14,275,706 in government grants received by the organization in 2017 include:

- $5,642,945 in various grants from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- $3,284,675 from the U.S. Department of Education for the Indianola Promise Community

- $3,114,998 from the Sunflower Childcare Coalition for early Headstart

- $1,376,231 from Medicaid Population Health.

Program services accounted for $14,391,625 of those expenditures.

Matthews was paid $417,576, with a base salary of $301,705, bonus and incentive compensation of $91,935, $18,102 in retirement and deferred compensation and $6,374 in nontaxable benefits.

Henry Womack Jr. is the Delta Health Alliance’s vice president of finance and administration. He was paid $217,191 in base salary, $28,917 in bonuses and $14,767 in retirement for a total of $260,875.

During the previous five years, Matthews was paid:

- A $294,012 base salary with bonuses of $87,616, $22,905 for retirement, $6,331 for a total of $410,864 in 2016.

- A $248,358 base salary with bonuses of $78,527 with $29,911 for retirement, $7,659 in non-taxable benefits for a total of $365,455 in 2015.

- A $294,012 base salary with bonuses of $87,615 with $$17,499 for retirement, $16,129 in non-taxable benefits for a total of $415,447 in 2014.

- A $248,358 base salary with bonuses of $78,527 with $29,911 for retirement, $7,659 in non-taxable benefits for a total of $365,455 in 2013.

- Compensation of salary and benefits totaling $415,217 with no separate breakdown for bonuses and other benefits in 2012.

According to data from the Mississippi Department of Employment Services, the average chief executive in the state makes $112,310 per year and an experienced one averages $151,460.

According to a 2016 report on non-profit CEO compensation by Charity Navigator, the median CEO salary at 4,587 charities examined in the report was $123,362. According to a graphic in the same report, a charity with a similar amount of expenses as reported by the DHA would pay their CEO a median wage of about $200,000.

Among its 52 programs, the alliance owns a medical clinic in Leland, tobacco cessation programs throughout the Delta and operates the promise neighborhood programs in Indianola and Deer Creek.

This Obama era program run by the U.S. Department of Education was created in 2009 and uses grants to non-profit organizations to help children growing up in distressed areas like the Delta have access to improved schools and better family and community support.

DHA received a five-year, $30 million grant from the U.S. for Indianola in 2013 and another similarly sized grant in 2016 for Deer Creek, thanks to influence of Cochran, who chaired appropriations in the Senate at the time.

The salary largesse wasn’t always the case with the Delta Health Alliance. As recently as 2007, the center only paid its two top executives, CEO Cass Pennington and then-chief operating officer Matthews (known as Fox at the time) she was about $110,125 combined. The program had about $4.66 million in revenue and about $4.53 million in expenses, with $3.65 million spent on program services.

That changed in 2008, when the group received a Delta Health Initiative Grant of $12,868,684 and the salaries of both Pennington and Fox received huge boosts. Pennington’s salary climbed to $94,066 while Matthew’s increased to $154,960.

With DHA’s revenues increasing to $28 million per year by 2011, Fox’s base salary was increased from $233,325 to $393,398.

Pennington was the executive director of the Delta Health Alliance from 2004 to 2008, is part of the DHA’s governing board and was later appointed by Gov. Phil Bryant to the state’s lottery board. He was the former superintendent of the West Tallahatchie School District and later led the Indianola School District.

Matthews was under the cloud of an investigation by the U.S. Attorney’s Office after a former employee who was fired in 2010 accused her of wrongdoing in his wrongful termination lawsuit that was settled in 2011. No charges were filed against Matthews.

Among the allegations included a lease on a condominium in Oxford, paying for two cars on top of a $3,000 a month car allowance and payment for her childcare.

The organization also paid the Delta Council, a powerful advocacy group of Delta farmers, community and business leaders, an average of $272,000 per year for administrative services.

The number of administrative personnel in Mississippi public schools increased by 51.1 percent from 1993 to 2018 while the inflation-adjusted spending on K-12 increased by 78.54 percent during the same span, according to analysis of data by the Mississippi Center for Public Policy.

In 1993, K-12 spending from state, federal and local sources added up to$2,737,277,644, adjusted for inflation. By 2018, that figure ballooned to $4,886,998,652, despite the number of students shrinking from 505,907 in 1993 to 470,668 in 2018.

While the number of public school students decreased by 6.96 percent, the number of Mississippi teachers increased by 10.13 percent

But despite the additional spending, student outcomes when judged by the ACT test remain mired in the doldrums.

Over the past 25 years, inflation adjusted education spending has gone up 78 percent while the number of public school students has decreased by 35,000 and ACT scores have largely remained flat

Composite scores on the ACT test from 1993 to 2018 remained largely static at 18.7, a solid determinant of student performance since all public school students in the state take the test and it measures readiness for college work in four subject areas.

These findings are in line with a report by state Auditor Shad White’s office. It showed that the growth in K-12 spending on administrative and other non-classroom costs from 2007 to 2017 outpaced the increase in the amount spent in the classroom.

According to the report, administrative costs increased 17.67 percent during the decade, while instruction costs increased 10.56 percent.

The biggest gain for administrative staff at Mississippi public schools wasn’t school administrators — which increased from 1,478 in 1993 to 2,003 in 2018, a gain of 35.52 percent — or district administrators, whose numbers went from 833 in 1993 to 976 in 2018, an increase of 17.17 percent.

Personnel listed as administrative support staff, either at the individual school or district level, increased 37.54 percent during that time.

The number of teachers increased from 28,376 in 1993 to 31,252 in 2018.

One gain in student performance has been on the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) tests administered to fourth graders.

In fourth grade mathematics, Mississippi students have improved from 202 in 1992, which was 17 points below the national average, to 235 in 2017, which is only four points below average. In 1992, only 36 percent scored at or above a basic achievement level in mathematics. In 2017, 77 percent were at or above the basic level.

On the fourth grade reading test, the state average score was a 215, six points below the national average. That’s a huge improvement from 1992, when the 199 average by Mississippi students was 16 below par nationally. In 2017, 60 percent of the state’s fourth graders were at or above a basic achievement level in reading. That’s a drastic improvement from 1992, when only 41 percent of Mississippi students were considered at least proficient at a basic level.

Between 2009 and 2015, the state’s average on the science test for fourth graders improved by seven points, rising from 133 to 140.

The data from the analysis came from the U.S. Census Bureau, the National Center for Education Statistics and the ACT board. The Census bureau releases an annual survey of school system finances, while the NCES issues an annual report on the number of students, teachers and other data. The ACT issues an annual report on how test takers perform.

In the debate over a wood pellet mill that is being built in George County near Lucedale, both sides are missing a key point.

The pro-mill side says Enviva’s $140 million pellet mill and a $60 million loading terminal at the port in Pascagoula will provide more markets for the state’s generous timber resources. The anti-mill side argues from an environmental viewpoint and that the mill would bring a danger to state residents due to increased health risks from emissions and airborne particles.

No one is talking about what the mill will cost taxpayers. Taxpayers statewide, through the Mississippi Development Authority, will be providing $4 million in grant funds, with $1.4 million for a water well and a water tank, while the other $2.5 million is for other infrastructure needs and site work.

George County will provide $13 million in property tax breaks over the next 10 years.

The company is expected to hire 90 employees in Lucedale, with 300 loggers and truckers possibly finding work supplying logs to the company.

All of those incentives, if realized, could add up to $17 million or about $188,888 per job.

The lost revenue will have an effect on George County’s budget over the next decade, especially since counties don’t receive sales tax revenue. According to the most recent audit from April 24, George County received $8,445,185 in property taxes.

Over the last four years, the county has taken in $32,051,659 in property taxes, an average of $8,012,915. Extrapolating this over a decade, the county could be expected to take in about $80 million in property taxes.

If Enviva realizes all of the property tax breaks, the county will lose 13.9 percent in potential revenue.

George County property tax receipts

| 2017 | $8,445,185 |

| 2016 | $8,278,200 |

| 2015 | $7,962,400 |

| 2014 | $7,365,874 |

The only winner during the first decade of the deal with Enviva might be the city of Lucedale, which could see a boost in sales tax revenue from the plant.

According to data from the Mississippi Department of Revenue, the DOR has disbursed $18,386,882 in sales tax revenue to the city from 2010 to 2018. The DOR disburses 18 percent of the state’s 7 percent sales tax to municipalities. In 2017, sales tax revenue ($2,204,988) represented 46.8 percent of the city’s $4.7 million budget.

Enviva is the world’s largest wood pellet producer and produces pellets to fuel overseas power plants. It has seven mills in the Southeast and one of those mills is in Amory, acquired in August 2010.

These wood pellets are made from low-grade wood fiber unsuitable for lumber because of small size, defects, disease or pest infestation; parts of trees that can’t be processed into lumber and chips, sawdust and other residue. The plant will mill, dry and pellet the wood in a press, using natural polymers in the wood called lignin to act as a natural glue.