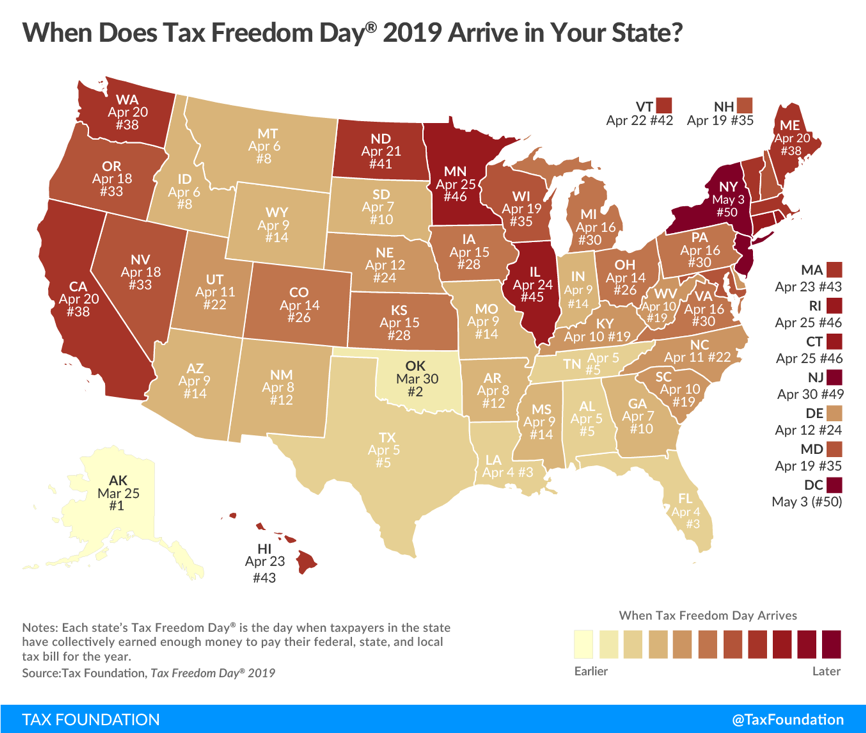

Today is a day to celebrate, if that’s the right word, as it is represents how long Americans have had to work in 2019 to pay the nation’s tax burden. It is now known as Tax Freedom Day. Congratulations, you are now able to keep the rest of the money you earn.

In 2019, Americans will pay $3.4 trillion in federal taxes, according to the Tax Foundation, and $1.8 trillion in state and local taxes. Income taxes, federal, state, and local, take the longest to pay, followed by payroll taxes, sales and excise taxes, and property taxes.

While Tax Freedom Day came before February 1 one hundred years ago before steadily moving later in the year throughout the 20th century, it has been moving in the right direction over the past few years. It was April 24 in 2015.

And on another bright side for Mississippians, we have actually been free since last week. New Yorkers, on the other hand, won’t be free until May 3.

That greedy, no-good 1 percent

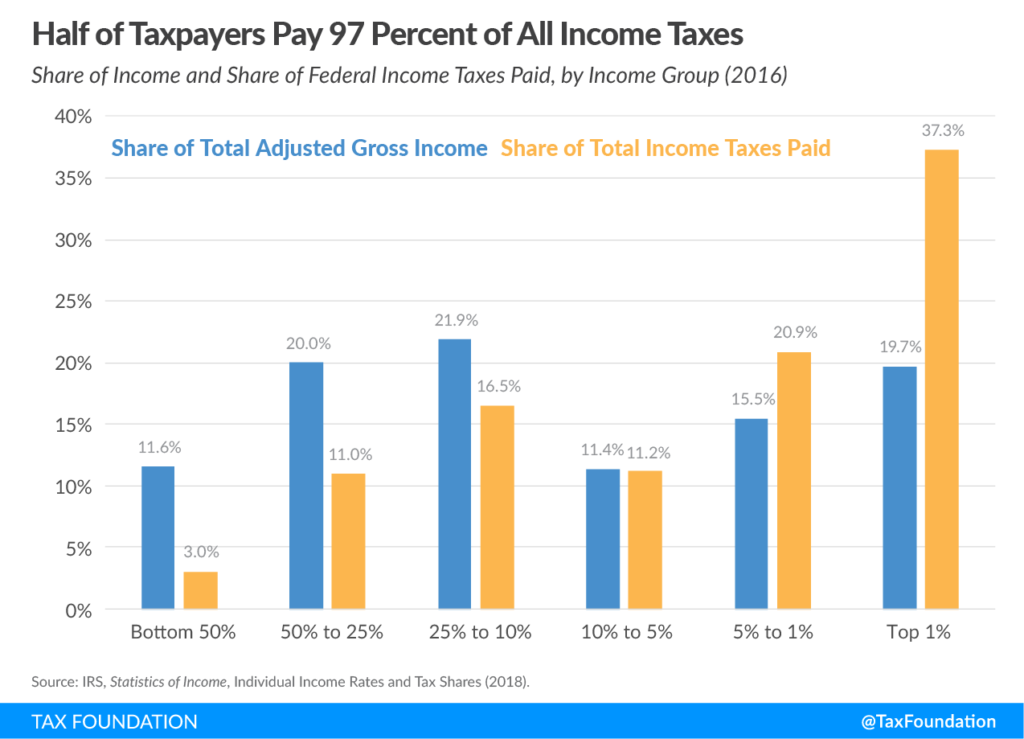

Who pays most of the taxes in America? Though it makes a good talking point, the “1 percent,” or the rich in our country, don’t get by with paying little to no taxes while the working man or woman has to foot the bill for everything. Higher income earners don’t pay lower rates as some like to claim.

These comments might win you the Democratic nomination for president, but we can look at the actual data provided by the federal government and see the true story.

In 2016, the top one percent of income earners paid 37 percent of federal income taxes despite earning less than 20 percent of the total adjusted gross income in the country, and, obviously, being just one percent of earners. The top one percent also paid a federal tax income rate of 26.9 percent.

Ninety-seven percent of income taxes were paid by just half of all taxpayers. Meaning the bottom 50 percent of earners paid just three percent of total income taxes. They also had the lowest tax rate of 3.7 percent.

That is because America has a very progressive tax structure. The more you make, you don’t just pay more in taxes proportional to your earnings, you also pay a higher percentage as a reward for your hard work.

So celebrate your Tax Freedom Day, maybe you can go and get a drink, and don’t worry about that 7 percent sales tax and the 1-3 percent local sales on top of that.

If you’ve gambled at a Mississippi casino at a dealer-served game or gotten a drink served by a bartender, your tax dollars probably contributed heavily to their education.

According to a report by non-partisan fiscal transparency group Open the Books, the Crescent City School of Gaming and Bartending — with campuses in Biloxi, Las Vegas, Memphis and New Orleans —received $9.5 million in funding from the U.S. Department of Education from 2014 to 2017.

The school offers a three-week bartending course, a 12-week beverage management course, and its gaming department trains potential dealers in blackjack, roulette, poker, baccarat and craps.

Mississippi as a state, according to the report, received $1.6 billion from the Department of Education in fiscal 2017, which included $241 million in direct payments, $480 million in grants and $912 million in loans.

California received the most, with $18.5 billion, followed by Texas ($12.5 billion), New York ($11.9 billion) and Florida ($9.49 billion).

The U.S. Department of Education spent $115 billion last year, with $5.9 billion going to the 25 colleges and universities with the largest endowments (a combined quarter trillion in existing endowments).

This included $2.3 billion in student loans in fiscal 2015 to 2016 and $1.2 billion in fiscal 2017 to 2018.

The Department of Education admitted that overpayments accounted for $11 billion of the money spent on funding higher education, with $7.1 billion in overpayments on direct loans and $4.1 billion as Pell Grants.

The Crescent City School of Gaming and Bartending wasn’t the only non-traditional school to receive money from the Department of Education. A school for video game development education, the DigiPen Institute of Technology, received $51.4 million from fiscal years 2014 to 2017.

The Professional Golfers Career College received $4.5 million between fiscal years 2014 to 2017 and the school teaches golf shop operations, methods of golf instruction, golf rules, and course management.

The Department of Education also paid $74.2 million from fiscal years 2014 to 2017 to the American Musical and Dramatic Academy, $43.5 million during that same time period to the a fashion college called the Laboratory Institute of Merchandising, and $10.4 million to a gunsmithing college called the Sonoran Desert Institute.

The 50 lowest-performing community colleges received $923.5 million in federal student loans and grants. Ten of these schools had an average graduation rate of 12 percent.

According to the report, for-profit colleges received $10.5 billion in fiscal 2017, with 10 of these schools receiving 30 percent of the funding, which included grants, direct payments, contracts and student loans.

Seminaries received $815 million from fiscal 2014 to 2017.

Giving Mississippi public school teachers a pay hike greater than the one passed by the legislature and spending vastly more on K-12 education would hit the state’s budget with a $385 million hammer blow.

The Republican-led legislature passed a teacher pay raise in the final days of the session that will increase teacher pay by $1,500 will cost $58 million annually. House Speaker Philip Gunn said Monday that the legislature is committed to appropriating that amount annually to cover it and that it isn’t a one-time pay hike.

Mississippi teachers have the nation’s lowest average salary ($44,926), but when cost of living numbers utilized by the North Carolina-based John Locke Foundation are used, the state’s teacher salaries now rank 35th nationally and 34thafter the pay hike takes effect.

Analyzing data shows that the $4,000 raise sought by Democrats during the final days of the session would cost $154 million annually. Adjusting the average ($49,574) for cost of living after this hypothetical $4,000 raise would move Mississippi up to 26th nationally.

Even with a $4,000 pay hike, the cost-adjusted average salary for Mississippi teachers would still trail Georgia, Tennessee, North Carolina, Arkansas and Alabama in the southeast region.

That’s not all that public education advocates claim that the state needs. They seek a massive salary increase for teachers and “full funding” for K-12 education under the Mississippi Adequate Education formula.

Increasing the general fund K-12 education budget to the amount dictated by MAEP ($2.477 billion) would add up to about $231 million. Combined with the money required for a $4,000 teacher pay raise and the bill would add up to $385 million.

This increase would be as much as the state’s debt service ($385 million) and more than the entire budgets for:

- The Department of Corrections ($316 million)

- Community colleges ($148 million)

- The state Department of Mental Health ($213 million)

The complex MAEP formula is designed to increase every year despite declining enrollment in Mississippi public schools.

It also doesn’t include some education programs or revenue from the state’s sales tax deposited in the Education Enhancement Fund ($299 million in fiscal 2018, with $214 million going to K-12) that is split between K-12, community colleges and universities.

Thanks to a state Supreme Court decision in 2017, the MAEP is no more than a funding request for the state’s public schools by the state Department of Education. The legislature isn’t compelled to follow its funding guidelines when appropriating for K-12 education.

Attendance at the taxpayer-funded MGM Park in Biloxi has decreased every year since the minor league Shuckers’ abbreviated inaugural season in 2015.

Those numbers aren’t even close to those predicted when the ballpark was proposed.

In 2018, the Shuckers had 160,364 fans through the turnstiles, an average of 2,259 per game. The team ranked seventh in the Southern League in average attendance. League averages that year were 226,183 fans and 3,388 per contest.

That’s not what a feasibility study commissioned in 2013 by the city of Biloxi predicted. The $25,000 study said the stadium would draw 280,000 fans annually, or about 4,117 per game. Those numbers would’ve put the Shuckers in the top five in the league in attendance.

The Biloxi Shuckers are the Class AA affiliate of the Milwaukee Brewers and they play in the 10-team Southern League, which includes teams in Pearl (Mississippi Braves); Birmingham; Chattanooga; Mobile; Pensacola; Seiverville, Tennessee; Jackson, Tennessee; Jacksonville and Montgomery, Alabama.

Those numbers are down from 2017, when the Shuckers drew 167,151 fans or 2,572 per game. That was good for eighth in attendance in the league, which averaged 3,684 fans per game.

Biloxi drew 180,384 fans in 2016, an average of 2,692 fans that put them eighth in average attendance. The league averages were 232,587 fans total and 3,445 per game that year.

In a 22-game home season in 2015, the Shuckers drew 3,252 fans to MGM Park. The team had to split time with its old ballpark in Huntsville, Alabama while its new home was still under construction.

The city of Biloxi borrowed $21 million to help build the $36 million stadium, which was also funded with BP settlement money and tourism rebate money from a state program. The team was lured from Huntsville, Alabama after playing in front of sparse crowds for years at what was the oldest stadium in the league.

Biloxi Baseball LLC could also receive up to $6 million from the state from the Tourism Rebate program. The state also provided $15 million in money from the BP settlement to help build the park.

Not all feasibility studies are created equal. The one for Birmingham’s Regions Field, which opened in 2013 and cost $64 million, predicted the ballpark would draw 255,300 fans in the first year and 240,800 in the fifth year.

The ballpark — which is located in downtown Birmingham — has outstripped those estimates, drawing a league-leading 391,061 fans in 2018 and 391,725 in 2017.

Total league attendance increased slightly in 2018 (2,261,834) from 2017 (2,171,934), but is still down from a nine-year high in 2014 of 2,367,710. Three teams — Pensacola, Birmingham and Biloxi — have built new ballparks during that time.

A fourth new stadium in Madison, Alabama near Huntsville will be the new home of the Mobile Baybears, who are relocating and changing their name to the Rocket City Trash Pandas. The new stadium will cost Madison taxpayers $46 million.

A feasibility study there predicts the team will draw 400,000 spectators in the first year and level off at an average of 350,000, which would put the team second to Birmingham in annual attendance.

Thanks to an increased tax revenue forecasts, the Mississippi legislature will be spending more taxpayer money going into an election year.

The state’s budget adds up to $6.3 billion, a 3.83 percent increase over last year’s $6.1 billion budget.

The fiscal 2020 budget goes into effect on July 1 and will include a 3 percent pay increase for state workers, a $1,500 pay hike for teachers and increased employer contributions to the state’s defined benefit pension fund.

Mississippi’s budget process is unusual in that there is no single budget document, but a series of appropriation bills for each state agency, board and commission. The Magnolia State is one of 30 states that use an annual budget cycle.

The general fund isn’t the only funding mechanism for appropriations, as some agencies have what are known as special funds, which are funded with fees generated from licenses and other income. Federal money, such as for Medicare, isn’t part of the calculations either.

These agencies will have increased funds in fiscal 2020:

- More than $82.1 million for K-12 education than last year’s appropriation.

- More than $37.4 million over last year’s appropriation for the state’s universities.

- Medicaid’s budget will climb by more than $27 million over last year’s outlay.

- A more than $15 million increase for the Department of Public Safety to conduct a new trooper school ($4.5 million) and $3.3 million for the Driver Support Division to hire more workers and reduce wait times at driver license centers.

- Community colleges will receive $14.3 million over last year’s appropriation.

Not every appropriation increased in the budget. Taxpayers will spend $385,241,392 next fiscal year to help retire the state’s more than $4.4 billion in debt, which is the same amount as last year.

Here are some that were actually cut when compared to outlays from last year’s budget:

- The state Port Authority, which manages the port at Gulfport, had its appropriation cut from more than $138 million to more than $66 million. The cut of more than $70 million was in line with the authority’s funding request that reflected a more than $63 million reduction in capital outlays.

- The state Department of Employment Security’s budget was cut by more than $14 million. This was still slightly more than the $137 million requested by the agency.

- The Attorney General’s office’s outlay was cut by more than $653,000.

The state’s budget doesn’t include the more than $371 million in borrowing for various projects that included $45 million for Huntington Ingalls Shipyard in Pascagoula, special states funds that are outside the general fund or federal funds.

In fiscal 2019, the budget with all general, special and federal funds included added up to $20,855.445.148, meaning the state remains the most dependent (42 percent of the budget) on federal funds.

Editor’s note: The Office of State Aid Road Construction receives its entire budget from special funds and not the general fund and its fiscal 2020 budget increased by only $103,555 over last year’s appropriation. A previous version listed a higher amount and we regret the error.

Mississippi teachers make less than their counterparts nationally in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, but when Mississippi’s low cost of living is taken into account, the state’s rank jumps to 35th nationally.

The John Locke Foundation performed an analysis using data from the National Education Association and adjusting the salaries using cost of living indices from the Council for Community & Economic Research (C2ER).

The same process can be applied to salaries taking into account the new $1,500 raise passed by the legislature. Mississippi is still the nation’s lowest average salary ($47,074) when 3 percent salary increases are given to the other states.

The state’s average-paid teacher ($45,574) will receive a 3.29 percent bump from the pay hike, which will cost taxpayers more than $58 million annually.

With the data adjusted for the cost of living ($54,929 in Mississippi), the post-pay hike average teacher salary jumps to 34th, ahead of states such as New Hampshire, Montana, New Mexico and Virginia.

In the Southeast, the adjusted salaries rankings put Mississippi ahead of South Carolina ($52,802.71) and Florida ($50,401.26), but behind Georgia ($64,529.73), Tennessee ($59,514.44), Arkansas ($59,445.21), North Carolina ($59,142.82), Alabama ($58,474.08), and Louisiana ($56,037.06).

If Mississippi’s average teacher salary was increased to $50,132 (10 percent increase), the state’s ranking would increase to 17th nationally ($58,497 with cost of living adjustment) and it would be the second-highest among Southeastern states behind Georgia (ranked 9th with an adjusted annual salary of $62,650).

The average teacher salary nationally is $63,635.46 when adjusted for cost of living.

Mississippi has the lowest cost of living nationally, while Hawaii, District of Columbia, California, New York and Massachusetts are highest nationally, according to the C2ER.

The House and Senate approved the conference report on Senate Bill 2770 on Thursday. The raise started as $1,000 raise phased in over two years and was increased in conference. Attempts to recommit the bill by Democrats in both chambers failed on largely party-line votes.

Some have called the $1,500 raise a “betrayal,” a “joke” and a “slap in the face.”

This is the third teacher pay hike since 2000. The legislature passed a $337 million plan in 2000 that was phased in over six years.

In 2014, the legislature passed a two-year plan that increased teacher pay $1,500 in the first year and $1,000 in the second year, costing taxpayers an additional $100 million.

Teachers in Mississippi receive annual raises after their first three years on the job and also receive pay hikes for earning higher certifications. A teacher in the lowest certification level starts at $34,390, increasing to $39,108 for the highest certification level.

A teacher with 20 years of experience will earn $43,300, while the highest classification nets $53,400. This is before local supplements, which can be several thousand dollars more per year in certain school districts.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average weekly salary in Mississippi is $752 or $39,104 annually.

Before the Mississippi legislature left town Friday as the session came to a close, it added $371 million in debt in the form of a large bond bill and several other bond bills for various projects.

Senate Bill 3065 adds up to about $207 million in additional spending that includes $85 million in borrowing for projects for the state’s universities, $25 million in projects at community colleges and $63 million for restoration of historic buildings statewide.

The House and Senate both signed off the compromise on Thursday and the bill needs only Gov. Phil Bryant’s signature to become law.

In a stunning admission while presenting the bill’s conference report, state Rep. Jeff Smith (R-Columbus) said that many of the projects were for “trying to help members that are going to have tough races.”

“We had some big-ticket items and this was the most for the IHL (Institutes for Higher Learning) that we’ve ever had,” said Smith, who is the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee. “Overall, this bill smells good.”

The “Christmas tree” bond bill isn’t the only bit of largesse being put on the taxpayers’ credit card.

There was also $86 million in projects for the Mississippi Development Authority, $12.5 million to help with the construction of the Mississippi Center for Medically Fragile Children, $7.94 million for the Water Pollution Control Revolving Fund and $3.5 million for improvements at Lauderdale County’s industrial park. All were signed into law by Bryant this week.

Bryant also signed House Bill 983 into law on Thursday. This law will give Huntington Ingalls Industries $45 million from state bonds.

The bill says the funds are for capital improvements, investments and upgrades for the shipyard, part of a three-year deal to help Huntington Ingalls.

It’s not the first time for Huntington Ingalls receiving money from state taxpayers, as the state has borrowed $307 million for Ingalls improvements since 2004. The company was awarded $9.8 billion in new contracts in 2018 and was just given a $1.48 billion contract Tuesday for the 14thSan Antonio class amphibious dock ship for the Navy.

Huntington Ingalls Industries received $45 million from taxpayers in 2018, $45 million in 2017, $45 million in 2016, $20 million in 2015, $56 million in 2008, $56 million in 2005 and $40 million in 2004.

The company leases the land for its Pascagoula shipyard from the state and is exempt from property taxes. It is one of south Mississippi’s largest employers, with 11,000 workers.

In addition to the San Antonioclass, Huntington Ingalls’ Pascagoula yard builds Arleigh Burkeclass destroyers, Americaclass amphibious warfare ships and the Legend class national security cutter for the U.S. Coast Guard.

The state already owes more than $4.441 billion in bond debt and legislators appropriated more than $285 million for debt service for fiscal 2020, which begins on July 1.

The legislature will also borrow $300 million for infrastructure needs under a deal reached in the 2018 special session.

Despite a new tax increase aimed at helping pay for tourism-related expenses, the city of Columbus is running out of money.

According to a story by the Associated Press, Columbus could run out of cash by Sept. 30, when the city’s fiscal year 2019 budget ends. With the city likely to spend $14.2 million before the fiscal year ends and only $10.9 million in revenue projected, the debt could add up to $300,000.

This isn’t the first time the city has been in financial trouble.

According to a November 24 story in the Columbus Dispatch, Columbus operated with an $881,000 deficit in fiscal 2018, which ended on September 30.

Since fiscal 2017, the city has run $1.7 million in deficits under the direction of former chief financial officer Milton Rawle. He resigned in February after more than five years in charge of the city’s finances.

Mayor Robert Smith told the AP that it’s not time for city leaders to panic and that he wants a property tax increase to go into effect for the fiscal 2020 budget, which begins on October 1. This would be the second tax increase to hit city residents this year.

The city will also receive a new 2 percent tax on restaurants that was approved by Gov. Phil Bryant earlier this session and goes into effect on Monday.

Another local bill in the legislature would add another 1 percent to the city’s now 9 percent tax on restaurant sales to pay for the second phase of the city’s new $5.5 million Terry Brown Amphitheater.

Passage is unlikely as the legislature’s session is drawing to a close this week.

Columbus isn’t exactly hurting for tax revenue, receiving $26,651,025 in fiscal 2018 alone. That’s more than similarly-sized Starkville ($20,785,798 in 2016), but less than Vicksburg ($31,165,725 in 2017)

Property owners in the city are assessed at a rate of 46.69 mills just to fund the city’s functions. That rate is average among Mississippi cities, with Jonestown in Coahoma County levying the highest rate statewide at 119.94 mills.

Mills are assessed per $1,000 of a property’s determined taxable value and the owner of an average priced home in Columbus ($128,200 according to real estate site Zillow) pays about $1,596 with an annual homestead exemption on the first $7,500 of value.

According to the latest numbers from the Mississippi Department of Revenue, the city received $718,119.46 in sales tax revenue, up $16,499 from this time last year.

Collections for the year so far are up slightly over the same time last year, with the city receiving $6,416,153.72 in sales tax revenue this year so far as compared with $6,421,907.56 last year.

Columbus taxpayers owe $28,550,411 in debt, with the annual debt service payment adding up to $528,868.

Vicksburg’s total debt adds up to $9,876,050, but Starkville taxpayers owe $55,652,465.

The Mississippi legislature could be approving as many as nine new tourism taxes this session, extending the effective date of six other existing tourism taxes and increasing a couple of existing tourism taxes.

These taxes start as local bills in the legislature and require an initial referendum by the citizens of the city or the county where the tourism tax is levied on hotels, restaurants or both. If a majority of residents approve, the tax goes into effect as local businesses remit the tax to the Mississippi Department of Revenue, who then sends the revenue back to the local government.

Here are some of the new taxes that have been approved or are being considered by the legislature this session:

Signed by Gov. Phil Bryant

House Bill 325– Columbus and Lowndes County have added a 2 percent tax on restaurants with annual sales in excess of $100,000 that will go into effect on April 1 and expire, unless reauthorized in 2020.

The city will receive $400,000 annually of the tax revenue for parks and recreation and special events, while the county will get $300,000 for the same purposes.

The economic development organization known as the Golden Triangle Development LINK will receive $250,000 annually to fund the promotion of community and economic development in the area. The LINK is classified as a 501(c)(6) by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service.

LINK gets most of its annual revenues from taxpayer funds, with 73.4 percent of its budget coming from taxpayers in 2017.

LINK Executive Director Joe Max Higgins’ salary has increased from $194,133 in 2011 to $358,534 in 2017. The amount the organization spends on payroll has increased from $194,133, when Higgins was the only paid employee, to $726,034 for a paid staff of six in 2017.

Higgins was made famous nationwide for his appearance on CBS’ 60 Minutes program in 2016.

Senate Bill 2854– The city of Charleston (population 1,958) would levy a 2 percent tax on restaurants and prepared food at convenience stores to promote tourism.

New taxes still in committee

HB 1682– The city of Columbus wants an additional 1 percent tax on restaurants to help fund the operation and maintenance of an amphitheater.

HB 1423– The city of Lexington with 1,523 residents would levy a 2 percent tax on restaurants and prepared food at convenience stores to promote tourism.

HB 1683– The city of Bay St. Louis, with a population of 13,043, wants to impose a 2 percent tax on bars and restaurants to fund tourism and parks and recreation projects in the city.

HB 1726– This would allow the city of Columbia (population 6,037) to authorize a 3 percent tax on hotels and restaurants for parks and recreation and economic development.

HB 1742– The city of Waynesboro (population 4,903) would impose a 1 percent tax on hotels and restaurants for tourism and parks and recreation improvements.

Tax extensions signed by the governor

HB 653– The city of Baldwyn had a 2 percent tax that expired on July 1. Despite notification from the Mississippi Department of Revenue, city businesses continued to collect the tax and have collected $11,983 from it so far this year. This bill will not only reauthorize the tax for the next three years starting on July 1, it will allow the city to receive the tax revenue collected by the DOR when the tax had expired.

New taxes or extensions awaiting the governor’s signature

SB 3074 would extend the repeal date of Pascagoula’s 3 percent tax on hotels — which expired in 2017 — to 2023 and would allow the city to retroactively collect the tax levied after the authorizing law expired.

SB 2185– The town of Carrollton (population 178) would impose a 2 percent tax on restaurants.

SB 2853– The city of Saltillo, with a population of 4,987, wants to levy a 2 percent tax on hotels and restaurants to pay for tourism enhancements, economic development and parks and recreation.

SB 2896– The city of North Carrollton wants a 2 percent tax on restaurants.

SB 2988 would increase Flowood’s tourism tax on restaurants from 2 percent to 3 percent and extend it until 2029.

Tax extensions still in committee

HB 1565 would add 1 percent to Starkville’s existing hotel and restaurant tax to pay for the construction of sports tournament and recreational facilities and extend the repeal date.

HB 1706 would extend the repeal date on the Jackson Convention and Visitors Bureau and its supporting 1 percent tax on hotels and restaurants. The bill would also change the requirements for the bureau’s governing board. The original billwould’ve added 1 percent to Jackson’s existing levy.

SB 3086 would reenact the 3 percent hotel and restaurant tax in the city of Amory until 2023.