Part II: The Mississippi Broadband Enabling Act of 2019

In February 2018, Mississippi Public Service Commissioner Brandon Presley announced an $11 million fiber infrastructure project aimed at spanning over 300 miles through 15 rural Mississippi counties. The project was a partnership between cable provider C-Spire and Entergy to bring the emerging fiber-to-the-home technology, which C-Spire had been offering to urban customers since 2013, to rural Mississippians.

Just one year later, Commissioner Presley lauded the strong bipartisan support for his new project, the Mississippi Broadband Enabling Act, which promised to bring fiber-to-the-home technology to the rest of rural Mississippi via the state’s rural electric cooperative associations (ECAs).

Presley told this author that the success of the legislation was the result of perfect timing. He cited the 2019 Mississippi statewide elections in which candidates (including incumbents) were well aware of the widespread support of Mississippians for universal broadband service availability.

Perhaps Presley was being modest. In reality, as reported by Geoff Pender in the Clarion-Ledger: “He created a task force that ended up with 1,310 members over 33 counties. … He got 60 county boards and 70 city councils to pass resolutions in favor of allowing rural co-ops to provide Internet service.”

Presley, in fact, succeeded in convincing lawmakers to reverse a 1942 law (enacted less than a decade after the state’s first rural electric cooperative association was established) that had barred ECAs from providing any product other than electric utility service to their customers. But beforehand, he had to win over enough of the state’s 26 ECAs to the idea that they could provide service even to the most remote customers (as they are required to do for electric utility service) without suffering financial losses.

At the time, only those with crystal balls could foresee the coming COVID-19 pandemic or that Congress – and the Mississippi Legislature – would authorize millions of dollars to make meeting their Internet service obligations that much easier – and less financially risky.

When HB 366 was passed, Presley called broadband “the electricity of the 21st Century,” and hoped for a day when children do not “have to sit in the McDonald’s parking lot to do their homework.” [Again, this was a year before COVID-19.]

Outgoing Mississippi Governor Phil Bryant boasted that, “If anyone wants to know how this bill got passed so quickly talk to the rural electric associations, because we do, and we listen to them.” Lawmakers passed the bill unanimously in the Senate after the House vote had just three “nays.” And with good reason – the ECAs serve 1.8 million of the state’s 3 million people and provide service to half of the state’s electric meters.

Similarly, Mississippi Farm Bureau Federation President Michael McCormick said farmers and ranchers in all 82 counties of Mississippi cited lack of connectivity as a top concern, along with the growing need for telemedicine and distance learning. Moreover, McCormick said, “I’ve talked to some real estate guys, and they tell me five or 10 years ago they would never have someone ask if high-speed Internet is available on a property. Now almost everyone asks the question.”

The 2019 law enables ECAs to establish or allow a separate broadband provider to use their systems to provide service. They can invest or use loans to cover startup costs, but cannot dip into revenues from providing electricity service to subsidize broadband. The law does not require ECAs to offer broadband, and several have so far not opted to do so.

No state funds were allocated for the ECAs, but some federal dollars were already available through existing programs. Then COVID-19 hit, and with it came a cornucopia of federal dollars and programs (see Part III of this series).

Responses by the state’s cooperatives varied widely. The Pontotoc Electric Power Association in February 2020 voted to discontinue its fiber-to-the-home project based on projected costs of $43 to $48 million and a paltry $1.9 million in currently available grant money. But by June 2020 (just before the Legislature voted to pass federal dollars to ECAs) 15 electric cooperatives were already working on plans to build fiber to the home in their coverage areas. All 15 were subsequently awarded one-to-one matching grants.

An elated Presley admitted that the ECA response “exceeds my wildest expectations. We had hoped we would have a couple step out there and then have a snowball effect.”

Part III of this report will discuss the federal CARES Act and federal funding for broadband stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic. Stay tuned.

Once You Buy In, You Can Never Leave

A few years ago, my wife and I wanted to take our kids to Disney World. As I was looking into hotel reservations, the sales agent asked if I’d be interested in listening to a “special offer.” I did and decided to purchase the 4-day/3-night package for $150.

I knew there would be a hard sell in exchange for this offer. I knew they’d be asking me to buy into a timeshare. Being a researcher, I did my homework and compiled my questions. To be honest, I wanted it to work. I like to travel, I like to stay at nice places, and I like to save money. So I went into it with an open mind.

The more I learned about the timeshare program, however, the more I realized it wasn’t such a good deal. I figured I probably wouldn’t get into the properties I wanted. I realized it would cost more than it seemed. In particular, there would be escalating annual fees that would soon make participation unaffordable. In the end, I discerned I would have more choice, at a more affordable price, if I didn’t buy into a timeshare.

I’m not saying timeshares can’t work for some people. For most consumers, though, they aren’t a good option.

I think you know where I am going by now. When I look at Medicaid expansion, even a Medicaid expansion like the Healthy Indiana Plan or the Mississippi Cares Plan, it looks a lot like a timeshare offer.

These are five reasons why this offer is not a good deal for Mississippi:

First, there is the price tag. Medicaid expansion has been much more expensive in every state than predicted, even Indiana. According to the Foundation for Government Accountability, Medicaid expansion has cost states, on average, 157 percent more than expected.

Their solid research is backed up by years of experience in other states. Consider that in 2014, then-governor Mike Pence promised:

“HIP 2.0 will not raise taxes and will be fully funded through Indiana’s existing cigarette tax revenue and Hospital Assessment Fee program, in addition to federal Medicaid funding.”

By 2019, hospitals were begging the state to raise taxes to pay for Medicaid expansion. Declared the Indiana Hospital Association:

“Hospitals support HIP by paying a state-based Hospital Assessment Fee (HAF). In 2019, the total HAF will surpass $1B. The hospitals’ share is increasing at an unsustainable rate, and increasing the cigarette tax can help provide necessary relief to hospitals.”

The Legislature responded by raising multiple taxes and creating new ones. Noted the nonpartisan Indiana Fiscal Policy Institute:

“Lawmakers had to adjust their final calculations to account for lower predicted sales and income taxes and higher-than-anticipated Medicaid costs. They looked to broaden the sales tax base by targeting online transactions through ‘market facilitators’ and hotel booking sites, and passed a massive gaming bill in the waning hours before adjournment to bring a jackpot of casino licensing fees and wagering taxes.”

In Mississippi, Medicaid expansion is going to cost at least $140 million a year, likely closer to $180 million. Some estimates are that we can expect additional enrollment as high as 360,000. This will cost us probably $200 million a year. One problem is that this population could be pretty expensive to cover, unlike children.

By the way, Medicaid expansion only applies to able-bodied, working-age adults. It does not cover kids (CHIP already does that). It does not cover the elderly (Medicare already does that). It does not cover the handicapped or disabled (We already do that with multiple programs). Medicaid expansion is about insuring adults who either are working or should be working.

Based on this fact, we might also wonder whether part of the intent in expanding Medicaid is to encourage people to drop private insurance in exchange for government-subsidized insurance. Nor should we be surprised that this seems to happen in every state that expands Medicaid. In Louisiana, some estimates found 3,000 to 5,000 people a month were dropping private insurance to get on Medicaid. Another study states that more than half of potential Medicaid enrollees already have private insurance.

The second reason Medicaid expansion is like a timeshare is because it is being pushed as a one-size-fits-all solution to multiple, complex problems. (No, that timeshare will not suddenly make vacationing with your in-laws more enjoyable.)

There is an economic principle called the Tinbergen Rule. This rule states that independent policy objectives should be resolved by independent policy instruments. A recent paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) points out in this context that using hospital payments to finance care for the uninsured is just plain dumb – and expensive. (Another NBER paper also verifies that hospitals (not the poor) are the primary beneficiaries of Medicaid expansion.)

In other words, the problems Mississippi hospitals claim are going to be addressed by Medicaid expansion would be better dealt with by using more targeted solutions, whether it’s providing health care to low-income families or helping rural hospitals adapt to changing demographics.

Third, just like that timeshare you “own” is not really yours, Medicaid is not really under Mississippi’s control. Medicaid is largely controlled by the federal government. Under the current administration, this means there is virtually nothing Mississippi will be able to do to limit Medicaid enrollment and costs. Consider that we couldn’t even get the Trump administration to approve a mild work requirement. The Biden administration will be even less inclined to approve any such reforms. Consider, also, that so-called free-market Medicaid expansions, like Indiana’s, will require a waiver from the federal government. But it’s a very safe bet that the only waivers the Biden administration will be granting are for projects that expand Medicaid costs and enrollment.

The fourth reason Medicaid expansion is like a timeshare is because the quality of Medicaid is not very high. (Indeed, this is where my analogy fails because I’m sure many timeshares are comparatively better!)

No doubt, there are excellent providers in Mississippi’s Medicaid program. Overall, however, Medicaid outcomes are far worse than outcomes for patients with private insurance. Medicaid expansion doesn’t even improve physical health outcomes. This is one of the troubling findings from the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment (OHIE), now hosted at the National Bureau of Economic Research. Another finding, as indicated above, is that hospitals – not patients – are the real beneficiaries of Medicaid expansion.

We don’t have space here to explain why Medicaid outcomes are so poor. Part of the reason is because many health care professionals refuse to participate in the program because of low reimbursement rates. (The “fix” for that will be socialized medicine.) Part of the reason is that Medicaid patients themselves don’t value Medicaid coverage all that much, as the OHIE study also found, and don’t seem all that invested in their own health care outcomes.

The fifth and final reason expanding Medicaid is a lot like buying into a timeshare is because the timeshare model works best if you have a presumption of scarcity. Today, the timeshare model does not work very well because we can use the power of technology – the Internet – to find better properties at a better price. We can also use technology to access properties on sites like Airbnb. If we could not do that and if there was a scarcity of properties, the timeshare model might make more economic sense.

I want to dwell on this point a bit more because this attitude of scarcity is deeply ingrained in Mississippi’s psyche. Good and valid reasons explain this, but it is important to recognize it nonetheless.

Fortunately, the health care economy is not a finite pie. Both the potential and actual supply of health care in America is not as scarce as it might seem. In fact, there are multiple pies – not just one or two – and these pies can get bigger.

Let me give an example.

A few years ago, a South African carpenter named Richard van As lost four fingers during a woodworking accident. Unable to work, Richard needed a new hand, but couldn’t afford a prosthetic hand. Instead of giving up, he started searching for alternatives. His quest led him to Ivan Owen, a puppeteer in Washington State. Working together and crowd-sourcing the initial costs, they used a 3-D printing press to manufacture a new hand for Richard. Today, people, especially children, can obtain such prosthetic hands for a couple of hundred dollars, if not for free. Perhaps you’ve seen them: Transformer hands, Iron Man hands, Spider Man hands, all manner of customizations are possible.

These kids, you see, could not get a prosthetic hand through Medicaid or even through their private insurance plans. The hands were too expensive: a $40,000 investment for a hand that a child would soon outgrow.

The scarcity mindset only sees the $40,000 hand and presumes there are only two ways of paying for it: public insurance or private insurance. We must reject this scarcity mindset for health care and for Mississippi’s economy.

We are told we have to expand Medicaid for a variety of reasons. All of them are rooted in this scarcity mindset.

First, you will hear that we should expand Medicaid because the federal money is just too good. The federal match for the expansion population is 90 percent. This conclusion is a non sequitur for two reasons. It’s like the timeshare guy offering to sell you a $10 million condo at a 90 percent discount. Once you get past how good the deal seems, you have to determine whether you have $1 million dollars. Second, the argument presumes virtually no one in Mississippi pays or will ever pay federal income tax.

Insofar as we do pay federal taxes, doesn’t it matter whether we forgo this federal spending if the evidence shows Medicaid expansion does not meet our needs? It is not true that other states are going to get our share of the Medicaid money pot. Medicaid is a welfare entitlement, which means that every person who is statutorily entitled to get on Medicaid has a claim to such services. There is no cap on Medicaid spending and there is not a separate Medicaid funding pot.

Granted, it is tempting to conclude that we should just take the federal money. Congress has no budget and America is bankrupt anyway. We might as well get ours while we can get it. If you believe this, the logical conclusion is that our federal government is absolutely corrupt and the whole budgeting process is a complete scam. In turn, the best play for Mississippi is to get in on the scam. If this is what you believe about America, so be it. But this Machiavellian view is not the legacy I want to leave to my children.

The second way the scarcity mindset comes into play regarding Medicaid is when we are told that medicine is socialized anyway, and that Medicaid expansion will be a more efficient way to provide health care to the poor. The suggestion here is that if we fund Medicaid expansion, commercial insurance costs – for private payers – will decline. This suggestion is explicit in material put out by the Mississippi Hospital Association.

A 2019 study by the state of Colorado utterly debunks this claim. The premise is that if fewer patients are uninsured and Medicaid pays more, hospital prices – and insurance premiums – for privately insured patients will decline. Medicaid expansion, we are told, is thus a good deal for commercial payers because it will reduce their costs. Except this is not happening – at least not in Colorado and certainly not in Indiana.

Indeed, according to the executive director of the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy & Financing, the hospitals used the “Medicaid expansion windfall to build free-standing [emergency departments], acquire physician practices, and build new facilities where there was already sufficient capacity. … Hospitals had a fork in the road,” concluded the director, “to either use the money coming in to lower the cost shift to employers and consumers or use the money to fuel a health care arms race. With few exceptions, they chose the latter.”

As an aside, Colorado’s experience gives us every reason to believe that expanding Medicaid will not primarily benefit rural hospitals in Mississippi, but urban hospitals.

The point I am making here is this: Even framing health care for low-income patients as a competition between Medicaid and private insurance is wrong headed. We can provide health care to these patients using other payment models and tapping into other supplies.

There are not only two pies: government-funded insurance OR private insurance.

There are other supplies of health care we are only beginning to utilize: direct primary care and telemedicine are two of them. There are also other payment models out there, such as health care sharing ministries and Association Health Plans. In many cases, it is government regulations that are preventing the emergence of more affordable choices.

Another option is hospital charity care. Mississippi has 111 hospitals: 45 are government-controlled (state/local, plus 4 federal); 31 are nonprofit; and 31 are for-profit. Shouldn’t public and nonprofit hospitals, which account for a large majority of hospitals in Mississippi, be mission-oriented toward providing subsidized care? In order to retain their tax-exempt status, nonprofit hospitals must provide a “community benefit.” This benefit is largely undefined and not particularly enforced.

This goes to show, however, that there are a multitude of free markets for health care and health insurance rather than the monolithic, health care bureaucracy that sees only the inefficient and expensive systems of Medicaid/Medicare and employer-based insurance as the only options. Again, there are not only two pies. There are multiple pies. Mississippi would do well to stop fighting over the scraps from D.C.’s broken health care promises and look toward creating a better framework that can help our people rise.

The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated the need to update Mississippi’s K-12 education funding model, in particular the way that the school finance formula counts students.

Mississippi differs from most states in the fact that they currently use an average daily attendance (ADA) model to count kids. This way of counting students is not all bad, but the COVID-19 pandemic has brought to light the already existing deficiencies of the ADA model and some Mississippi school districts are at risk of losing a significant amount of funding because their ADA has declined during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Surprising variation exists in how states measure public school enrollment. These measurements are important because they ultimately affect how education dollars are allocated to students and schools. Every way of counting kids comes with important tradeoffs: some are more accurate than others; some impose a greater administrative burden; others result in more budget stability. This commentary will survey the current student counting methods used across states and make policy recommendations that Mississippi policymakers could employ to address funding shortfalls resulting from a decline in ADA counts.

Key Considerations: Accuracy, Predictability and Budget Stability

There are some key considerations states make when they take different approaches to counting students. Keep in mind that there are drawbacks to each of these considerations.

The first priority for legislators weighing different student count methodologies should be accuracy. Accuracy is the key to fair funding insofar as the entire point of counting student enrollment is to correlate enrollment with funding. To be funded, a student must be counted.

To the extent that any other factors obscure the principle that funding should be determined by the true number of students a district currently has enrolled, inequities will emerge. Concerns over accuracy and funding equity are the reason some states opt to use average daily membership (ADM). This way of counting differs from ADA in that ADM averages student enrollment numbers—rather than attendance numbers—over much of the school year. Enrollment is considered more accurate in this case because it counts the number of students a district expects to serve, not the number that show up on a given day. North Carolina, Tennessee, and West Virginia, along with many other states, use ADM.

Second, there is generally some acknowledgement that school districts must be able to reliably craft their yearly budgets. If state funding varies too much over the course of a year due to attendance fluctuations , districts won’t be able to make confident hiring or programmatic decisions. If, as it’s generally assumed, student bodies are largest at the beginning of a semester, districts must structure their staffing and budgets without good knowledge of which students and how many of them will end up withdrawing. These budget concerns are the reason some states use single-day enrollment counts at the beginning of the year (Colorado, Maryland, Massachusetts) or at only several points over the course of the year (Georgia, South Carolina, Louisiana).

A third key consideration for state lawmakers when deciding on a student counting system is that districts struggle to adjust their cost structures when student bodies are changing substantially over a short span of years. When student bodies are shrinking or growing rapidly, districts must make long-term decisions about consolidating or expanding school facilities. With staffing, they often can only downsize through attrition when populations are shrinking. Likewise, schools face additional hiring costs when student populations are growing. Because these long-term investments take time and often lag behind the speed at which student populations are changing, some states (Maine, Nevada, North Carolina) allow districts to incorporate older or projected student counts so that they have a financial cushion to accommodate substantial increases or decreases in student populations.

Lastly, many state policymakers believe funding decisions should emphasize school attendance metrics. Under this model, the reigning assumption is that time spent in a physical classroom directly translates into student achievement. A primary rationale for the small number of states (Mississippi, California, Illinois) that count students through attendance, rather than enrollment, is that they want to encourage districts to get students in their classrooms.

Click here to read the rest of this report.

The Magnolia state might be one of the most wonderful places to live, but there is no getting round the fact that it has some of the worst health outcomes in the country.

According to the Legatum Institute’s Prosperity Index, Mississippi ranks 49th out of 50 states in terms of health outcomes, health systems, and illness and risk factors.

“That’s easy to fix” some are now saying. “We just need to hose federal funds at the problem”. When it comes to health care, one thing Mississippi does not lack are those calling for us to accept federal funding to expand Medicaid.

Under the Obama administration’s Affordable Care Act, a number of states have already gone down that road, turning Medicaid – which was designed to provide health insurance coverage to low income seniors and mothers, and those with disabilities - into a system of generalized healthcare. Should we do the same?

No. Expanding Medicaid would be extremely costly, without necessarily improving health outcomes. Spraying federal funds in our direction does not mean that the money will end up going where it is actually needed. Another large handout from DC would likely hinder, not help, the chances of us achieving the kind of health reforms we actually need.

Pouring millions of dollars of federal funds into Mississippi’s health system sounds attractive, but you won’t be surprised to learn that it comes with a price tag; a $100 million a year price tag, according to recent estimates.

Who, it seems reasonable to ask, would have to pay that?

One way of generating an additional $100 million a year in revenue from tax-paying Mississippians would be to raise personal income tax or tax businesses even more. But Mississippi already has one of the heaviest state and local tax burdens of any state in America, and it is hard to see how our fragile economy could cope with an additional hike.

Some have suggested that we could find this additional $100 million a year from the hospitals. No plan I have yet seen has identified a way of conjuring up that kind of money without hospitals ultimately bumping up their costs to their patients.

I can see why some hospitals might be quite attracted to the idea of raising an additional $100 million a year from their patients, and in return getting a large dollop of federal funding thrown in their direction. But I can’t quite see what is in it for those hundreds of thousands of families in Mississippi who work hard to provide health care coverage for their families, who would find themselves being asked to provide even more – so other folk could get coverage for free.

If we want better health outcomes, we should not think only in terms of how much money we spend on health care. We need to think about the way that our health care system converts that money into improved outcomes for patients.

One low cost thing we could do would be to repeal laws that unnecessarily push up health costs, such as the 1979 Health Care Certificate of Need (CON) Law. This legislation means that it is illegal today in Mississippi for hospitals or other healthcare providers to expand their health care services without first getting a permit, known as a certificate of need.

It’s not just that permission is needed. The way our restrictive system works is that permission is often needed from established health care providers. They can file objections that keep the matter tied up, often for years. It is as if Papa John’s had to give approval before Domino Pizza was allowed to open a new restaurant in your neighborhood.

Additionally, rules on telemedicine mean that Mississippians are presently prevented from accessing health care online – unless the doctor they are dealing with happens to have Mississippi licensure.

Why can Mississippians not deal with a doctor from Birmingham or Memphis? Is what comprises good medical care different there? Of course not. The rules governing who can provide health care have been written in a way that hinders competition and limits choices, and is holding health care back for Mississippians.

These type of restrictions mean that instead of a free market in health care, with different providers competing to give patients services at a price they can afford, we have a rigged market. The rules are written to keep new entrants out, which in turn leaves prices high and customers captive. This, not a failure to sign up to Obamacare, is one of the reasons why Mississippi does not have better health outcomes.

Without reforming the way that our health system operates, throwing hundreds of millions of dollars at our state Medicaid system is not going to make things better.

Part I: The 2009 ARRA

Over the past 10 years, hundreds of millions of federal dollars have flooded into Mississippi with the stated aim of extending broadband Internet connectivity into underserved and unserved, mostly rural areas of the state. It is vital that the distribution and use of these monies be subject to close scrutiny. The federal funds themselves were drawn out of thin air via deficit spending, so it is doubly important that the real-world return on these massive investments (which are being replicated nationwide) be maximized and any potential for misuse, abuse, or waste minimized.

Federal dollars for rural broadband first flowed into Mississippi and around the nation via the 2009 American Restoration and Reinvestment Act (the Obama stimulus). The total was nearly $110 million ($133 million adjusted for inflation 2020). A decade later, theCoronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act of 2020 would bring another $1.25 billion into Mississippi. State lawmakers earmarked $275 million of that money to broadband and distance learning, with $75 million going to rural electric cooperatives and privately owned rural Internet providers (via a dollar for dollar matching grant).

Of the 2009 money, more than $70 million was allocated to the Mississippi Education, Safety and Health Network (MESHNet) project to deploy a 700-megahertz interoperable public safety wireless broadband network to every public safety agency in the state.

Another $32 million was administered by a contractor, Contact Network, Inc., for two projects. The South Central Mississippi Broadband Infrastructure Project intended to build 635 miles of fiber optic middle mile broadband infrastructure and lease another 223 miles of existing commercial fiber. These two efforts sought to expandhigh-speed Internet access in underserved areas of 16 counties in southern and central Mississippi.

The Mississippi Delta Broadband Infrastructure Project was approved to deploy a 550-mile broadband middle mile network throughout 12 Delta counties. This was to enable community anchor institutions to complete a fiber network with the capacity to upgrade with increased demand. A second objective was to connect 16 public school districts to facilitate distance learning, video conferencing, and improved school security.

The fourth project funded through the National Telecommunications and Information Administration allocated $7.2 million to support creation and operation of the Mississippi Broadband Connect Coalition, a nonprofit public-private partnership focused on producing a comprehensive statewide strategic plan for improving digital literacy, increasing access to broadband, and enabling greater adoption of broadband in Mississippi.

The Quest for Universal Internet Access

Mississippi has been singled out as one of the worst states in the nation for Internet access and, especially, for failing to provide access to largely poor rural citizens. When you dig deeper, the picture is more complicated, especially in considering actual broadband adoption rates by households who already have access to broadband. (In fact, some people live happily without broadband and don’t choose to purchase it even when it is available.)

BroadbandSearch.net says a startling 41 percent have no Internet connectivity – the highest rate in the nation. Yet the firm also states that nearly all (statistically 100 percent) of Mississippi residents have access to wireless Internet, 87.3 percent can get DSL service, 67.8 percent can get cable Internet, and 21.5 percent have fiber Internet as a choice. Over half of Mississippians have at least three Internet service providers to choose from.

Broadband Now, which has been manually collecting plan and pricing data from all U.S. Internet service providers every month since 2015, reports that Mississippi is currently among the 10 worst states for broadband access due to the relatively low statewide average download speed of 84.5 Mbps (thousand bytes per second) and the fact that over 16 percent of people remain without access to a high-speed wired broadband connection of 25 Mbps or faster, Yet, they state that 40 percent now have access to fiber optic service, which is well above the national average. This contrast may be explained by current federal practice, which prioritizes broadband speed over broadband coverage.

Broadband Now also states that some Mississippi counties have widespread broadband coverage while others have less than 50 percent coverage. The bottom line:

- Some 368,000 people in Mississippi out of an estimated 3 million residents do not have access to a wired Internet connection capable of 25 Mbps download speeds;

- 258,000 have NO available wired Internet provider;

- Another 236,000 have access to only a single provider.

These are significant numbers, but they do not tell the whole story.

One in 10 Americans do not use the Internet at all, with the elderly and high school dropouts most likely not to go online. The largest group of Internet nonusers are people who believe the Internet is not relevant to their lives or that it infringes on their privacy. Recently imposed restrictions by providers on Internet content, as well as questions about the extent to which schools are teaching various radical ideologies, may be signaling that a battle is coming about how government-funded Internet could be used to shape the hearts and minds of Internet users.

Another Pew Research report indicates that, “Only 36% of rural adults say the government should provide subsidies to help low-income Americans purchase high-speed home internet service, compared with 50% of urban residents and 43% of suburbanites.”

That said, in some rural areas, wireless Internet is both costly and interruptible. The lockdowns, lockouts, and home-based work and education brought about in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic has provided a new sense of urgency to get the entire state “wired.”

The ARRA Brings Federal Dollars to the Broadband Buildout in Mississippi

Back in 2008, a Pew Research study found that “broadband adoption in the United States continues to exhibit steady growth,” with 55 percent of Americans having a high-speed Internet connection at home, up from 45 percent a year earlier. Another 10 percent had dial-up connections. The study also found stagnant growth in usage for low-income and African-American households, but rapid growth among Americans ages 50-64 and among suburban and rural Americans. Still, only 38 percent of rural Americans had broadband at home in 2008.

It is thus not surprising that, during his campaign to win the White House, then-Senator Barack Obama listed broadband rollout to rural areas as one of his top priorities. At the time, Congress was approving the Broadband Data Improvement Act, which directed the Federal Communications Commission to compile a list of geographical areas in the U.S. lacking any “advanced telecommunications” provider and to include population and per capita income data for each area.

Shortly after his election, President Obama included $7.2 billion for rural broadband in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, the giant stimulus bill intended to jumpstart the nation out of the doldrums of the “Great Recession.” Distribution of the funds was split between the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural Utility Service ($2.5 billion) and the National Telecommunications and Information Administration ($4.7 billion). Nearly $110 million in ARRA funding came through NTIA to various projects in Mississippi.(The specific distributions to Mississippi entities from the Rural Utilities Service out of its ARRA allocation are still being researched.)

Obama’s commitment to public funding for rural broadband expansion was met with optimism in many quarters. Verizon official Link Hoewing encouraged grants to states to map out areas where broadband was not available, adding that “relatively small investments in broadband can encourage substantial returns in economic growth, new jobs, and innovation.”

But a 2011 paper by Jeffrey Eisenach and Kevin Caves confirmed prior research that had indicated that RUS broadband subsidy programs funded by the ARRA “were not cost effective and often funded duplicative coverage in areas already served by existing providers.” As Nick Schulz reported in Forbes, Eisenach and Caves looked at three areas that received stimulus funds, in the form of loans and direct grants, to expand broadband access in southwestern Montana, northwestern Kansas, and northeastern Minnesota.

In these three areas, where the median household income at the time was no higher than $51,000 and the median home price no higher than $189,000, the RUS-subsidized projects spent a whopping $394,234 per household, over twice the high-end median home price and nearly eight times the high-end median household income. A $49 million project in the state of Montana, in an area with only seven households lacking at least 3G Internet wireless, was the biggest boondoggle.

In the years following, broadband penetration in the United States continued its rapid expansion across the country. By 2018, roughly three-fourths of American adults had broadband Internet service at home and 90 percent were Internet users.

Even so, Pew Research found again that racial minorities, older adults, rural residents, and those with lower levels of education and income were less likely to have broadband service at home. These statistics, however, did not take into account that about 20 percent of American adults, largely younger adults, non-whites, and lower-income Americans, had become “smartphone-only” Internet users.

As the Mississippi Broadband Connect Coalition was winding down its federally funded activities in 2013, Jason Dean, then its managing director [he is now President of the State Board of Education], said regarding broadband availability in Mississippi: “There’s a lot of coverage if you take in cable and cell phones, but we’re trying to get more people to use it. Education, health care, government services, and workforce training have to create demand drivers.”

A 2015 order from the Obama Federal Communications Commission overturned laws in 19 states that had prevented local governments from attempting to build out and compete with privately held broadband networks. In the aftermath of that action, the Mississippi legislature enacted the Mississippi Broadband Enabling Act of 2019, overturning a 1942 state regulation that prevented electric cooperatives from offering anything other than electricity to their members.

Part II of this report will discuss the Mississippi Broadband Enabling Act and the politics behind that. Stay tuned.

President-elect Joe Biden says he wants Congress to raise the federal minimum wage from $7.25 to $15 per hour.

About time too, you might think, seeing as there’s not been an increase in the minimum wage in over a decade. If everyone in America has to be paid at least $15 an hour, it would boost pay checks and reduce poverty, right? Wrong.

What sounds like a good idea in Washington DC might actually be bad for Mississippi – and here’s why.

Passing a law to force every business to pay everyone at least $15 per hour does not suddenly make every employees worth $15 per hour.

If a local business is currently paying one of their new entry level staff say $12 or $14 per hour, raising the minimum wage will mean one of two things; either the employer takes the loss and pays someone more than they are worth, or they let them go.

Making it more expensive to hire people means that fewer people will be hired. Instead of a bigger pay check, for some there will be no pay check at all.

Right now in Mississippi, according to federal estimates, around 4 percent of people are on the minimum wage. Studies suggest that these tend to be employees coming into the labour market in entry level positions. In other words, they are likely to be on the minimum wage for only a short period of time before they progress up the pay scale and earn more.

Far from helping employees, doubling the minimum wage would make it illegal for some people to sell their services to a local employer.

“But businesses can afford to pay more” I hear some people say.

Really? Some businesses will be able to, not because they have a magic supply of money, but because they will be able to pass on the costs to the customer. But what about some of the smaller local business where you live?

Thanks to Covid, many smaller firms in the retail and service sectors are already struggling. Many simply won’t be able to afford higher wages, or pass on the costs to their customers.

Do we really want to introduce a measure that will hit small, independent businesses hardest? There are plenty of local ministries in our area that are going to struggle with higher costs, not to mention start-ups.

Wealth doesn’t come from passing a law that gives one group of people a legal right to resources. It comes instead when entrepreneurs are free to bring people and ideas together and give customers what they want. If the minimum wage is set too high, it makes it harder for that to happen.

Imposing a $15 per hour minimum across the whole country makes no allowance for the condition of the local economy. Insisting that a uniform rate apply right across America, in Mississippi as well as Massachusetts and Michigan, just doesn’t make sense.

If there is to be a minimum wage at all, then we should at least allow different states to set the rate according to the condition of their economy. That way we could see the effect of the different rates in each state. If one state set the rate at say $16 per hour, with no discernible downsides, we could follow suit. If, on the other hand, a high rate in one state led to higher unemployment and business failure, we would know not to do the same.

Washington seldom gets things right when it imposes a one size fits all plan. It’s time to let each state decide on this for itself.

This article first appeared in the Madison County Journal.

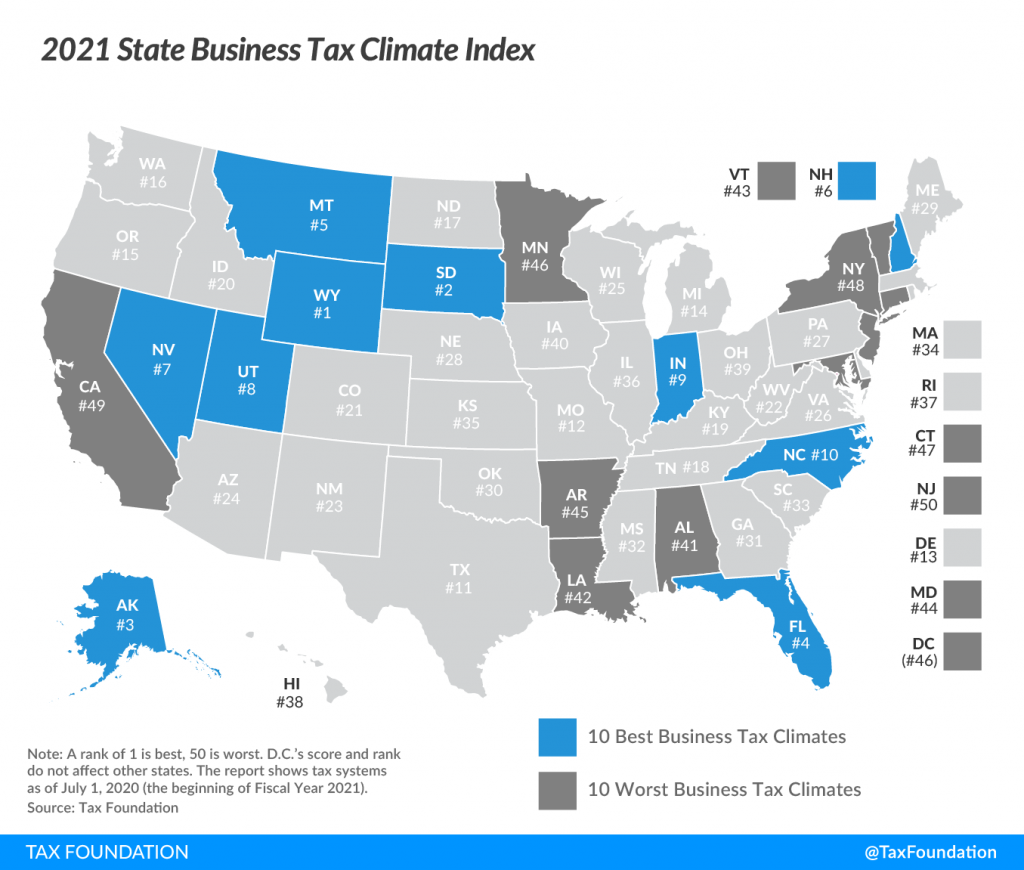

Mississippi’s business tax climate dipped slightly last year as it remains in the bottom half nationally.

The Tax Foundation placed Mississippi 32nd overall for taxes, including corporate, individual, sales, property, and unemployment insurance taxes. The only neighboring state to do better was Tennessee. Alabama, Louisiana, and Arkansas were rated 41, 42, and 45 respectively.

The top five states remained the same. Wyoming was again the top-rated state, followed by South Dakota, Alaska, Florida, and Montana. Not surprisingly, the bottom five states were New Jersey, California, New York, Connecticut, and Minnesota.

“Business taxes affect business decisions, job creation and retention, plant location, competitiveness, the transparency of the tax system, and the long-term health of a state’s economy,” the report noted. “Most importantly, taxes diminish profits. If taxes take a larger portion of profits, that cost is passed along to either consumers (through higher prices), employees (through lower wages or fewer jobs), or shareholders (through lower dividends or share value), or some combination of the above. Thus, a state with lower tax costs will be more attractive to business investment and more likely to experience economic growth.”

Mississippi dropped a spot from last year, not because the tax climate in Mississippi has worsened, but because other states have improved.

The state received its best marks for unemployment taxes (5th best) and corporate taxes (13th best). The corporate tax component measures impacts of states’ major taxes on business activities, both corporate income and gross receipts taxes. The unemployment insurance tax component measures the impact of state UI tax attributes, from schedules to charging methods, on businesses.

Mississippi’s worst tax categories were property and sales. It would be a good idea to lower our business tax burden on land, buildings, equipment, and inventory.

Mississippi’s business tax climate is part of the reason the state relies so heavily on corporate welfare for enticing businesses. Instead of offering taxpayer incentives or tax abatements to select companies, the state should begin the process of improving the tax climate for all businesses rather than just those who curry political favor.

Mississippi lawmakers have been rebuilding the state’s rainy day fund since it was nearly depleted last decade. And today the state is doing better than many others when it comes to saving.

This is something that always been relevant, but became exceedingly important from the COVID-19 related recession.

The balance of the rainy day fund has been steadily growing to around $460 million today. This represents a healthy eight percent, which is comparable with the national average of general fund expenditures. In 2013, it stood at just $32 million, about 0.7 percent of all expenses.

Mississippi’s rainy-day fund

| Year | Rainy-day balance | % of expenses |

| 2013 | $32,000,000 | .7% |

| 2014 | $110,000,000 | 2% |

| 2015 | $395,000,000 | 7.1% |

| 2016 | $350,000,000 | 6.1% |

| 2017 | $269,000,000 | 4.7% |

| 2018 | $295,000,000 | 5.3% |

| 2019 | $350,000,000 | 6.3% |

| 2020 | $465,000,000 | 8.1% |

| 2021 | $464,000,000 | 7.9% |

As for neighboring states, Mississippi is doing better than most. Alabama is the only state where the rainy day fund makes up a larger chunk of their budget, at 10.9 percent. Tennessee, Louisiana, and Arkansas have rainy day funds of 6.8 percent, 5.8 percent, and 2.7 percent, respectively.

Rainy day fund, neighboring states

| State | % of expenses |

| Alabama | 10.9% |

| Arkansas | 2.7% |

| Louisiana | 5.8% |

| Mississippi | 7.9% |

| Tennessee | 6.8% |

“Rainy day funds are a reflection of deliberate state policy choices by elected officials. In recent years, governors and state lawmakers have focused on rebuilding their states’ rainy day funds. Rainy day fund balances, in the aggregate, have grown substantially since the Great Recession, reaching $75.5 billion in fiscal 2019 (with a median balance of 7.3 percent as a share of general fund spending). Before the COVID crisis, states were expecting to end fiscal 2020 with a median rainy day fund balance of 7.8 percent, a new all-time high. By comparison, going into the last recession, the median rainy day fund balance in fiscal 2007 was 4.6 percent,” the report notes.

Mississippi’s rainy day fund, while smart fiscal policy, has been a bit of a political football with some lawmakers criticizing the state for saving while they push for more government spending during better economic days. But this prudence paid off when the coronavirus pandemic and the associated economic collapse hit earlier this year. Yes, the federal government has dumped boats of cash in Mississippi and every other state, but that can’t and shouldn’t be what any state turns to during bad times.

Especially in Mississippi, a state that relies on the federal government more than most states.

We’ve learned from the Great Recession to be prepared. And that is what will help the state be prepared fiscally for the future. It is about making smart fiscal decisions, particularly during good times, resisting the temptation to spend every dollar you have, and living within your means. It’s something households do every day.

It’s something all states could and should do.

The long-term financial stability of the Public Employees’ Retirement System of Mississippi could be at risk. Despite a historic bull market run, PERS fell $9 billion further into debt to public employees over the past decade, reaching a record high $18 billion in accrued, yet unfunded, pension benefits prior to the global pandemic.

As of 2019, PERS held only 61 percent of the assets actuaries expect are needed to pay for long-term benefits to state and local public employees. Given recent market volatility and the global recession, this funding challenge is likely to get worst if action is not taken soon.

According to recently released analysis by the Pension Integrity Project at Reason Foundation, the lead driver of PERS’ growing unfunded liability has been overly optimistic investment return assumption. Going back decades, PERS depended on a return of 8 percent and eventually adjusted that expectation down to 7.75 percent in 2015. Unfortunately, actual returns only averaged 5.94 percent since 2001. Looking forward, experts suggest achieving even a 6 percent average rate of return is optimistic over the next 10-15 years.

Using actuarial modeling to test future crisis events with varying market returns, the Pension Integrity Project has found under a wide range of realistic scenarios, Mississippi’s assets are not able to keep up with the growth in promised benefits without major cash infusions.

The results should concern any pensioner, policymaker, or taxpayer.

Such scenarios could result in annual costs more than doubling within the next 30 years – pulling funding from other public priorities like road repairs and education.

Beyond the state’s obvious funding issues, policymakers also need to reevaluate the effectiveness of the current system at providing attractive benefits to all its members. Most workers (71 percent) leave before vesting—within 8 years of service—and are required to forfeit employer contributions to their retirement account. Only a mere 4 percent of workers remain in the system long enough to enjoy full pension benefits, leaving the vast majority of PERS members without a path to a secured retirement.

When it comes to the retirement security of Mississippi’s public workers, there is no better time for stakeholders to come together and adopt meaningful change than now.

The plan’s inability to recover even during the longest bull market run in U.S. history highlights the need for a change. Lowering the assumed rate of return as well as prioritizing paying off the current unfunded liabilities as fast as possible should be at the top of the to do list for state lawmakers. Undoubtedly, this will be difficult to prioritize amid many competing fiscal priorities facing the state in the coming years, but the value of meaningful and lasting reform would extend well beyond this challenging moment.

PERS finds itself in a precarious position, but it is not too late to right the ship. If state policymakers take swift action to make informed and lasting improvements, they very well could save the retirement security of Mississippi’s public workers.

This column appeared in the Clarion Ledger on August 3, 2020.