A non-profit organization that deals with healthcare and education programs in the Delta is in the process of paying back $1 million from a federal grant to taxpayers for spending disallowed by federal rules.

According to a 2015 decision by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Delta Health Alliance — a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization that receives most of its money from taxpayers in the form of federal and state grants — had to pay back $1 million out of more than $34 million in grants for healthcare and educational programs in the impoverished Delta region.

According to the organization’s 2017 audit, the organization will pay back the $1 million over a period of 10 years, interest free, with payments of $100,000 paid annually in a deal it reached with the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration in 2017.

Some of these costs disallowed in the HHS decision included new furniture for the DHA’s offices in Ridgeland and costs related to a gala at the B.B. King Museum to celebrate the one-year anniversary of one of the programs covered under the grant.

The Health Resources and Services Administration, which is an agency of the HHS, determined that the alliance spent more than $1 million on disallowable items in 2014. The DHA appealed the determination before the Departmental Appeals Board, which issued the final decision on March 12, 2015.

When a federal agency supplies a grant, the money comes with restrictions on how it could be spent. The U.S. HHS disallowed some of the spending by the DHA from 2009 to 2011 under the grant. Some of these included:

- $152,474 in payments made for an information technology consulting contract with the Coker Group that included $31,000 and $33,900 for a chief information officer consultant, travel costs plus the costs of renting an apartment along with furniture and utility costs.

- $79,584 for payments to the Keplere Institute for a summer program that provided workforce training in pharmacy technology unrelated to the grant’s purpose.

- $77,998 for direct and indirect costs for charges made for travel and other expenses to the DHA credit card.

- $69,965 for a contract with the Compass Group, which was hired to develop fundraising strategies for the organization for when the grants expired.

- $48,785 in direct and indirect costs for travel and telephone allowances by DHA employees.

- $45,727 in direct and indirect costs for furniture for DHA’s Ridgeland office.

- $42,182 for DCG Inc. for policy development, statistical analysis and consulting services that benefitted other work by the DHA unrelated to the grant.

- $27,575 for payments to external reviewers hired by DHA to assist in evaluating proposals for projects funded by the grant.

- $17,768 for promotional items, sponsorships and other costs.

- $11,232 in direct and indirect costs for event costs that included the rental of space and refreshments for a celebration at the B.B. King Museum to celebrate the one-year anniversary of the Indianola Promise Community, one of the programs covered by the grant.

According to the audit, 70.84 of the DHA’s 33.12 percent of the DHA’s funding in 2017 came from the U.S. Department of Education and 37.72 percent came from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The organization has received $10.6 million over the past four years from state taxpayers for a technology-based program to help providers reduce preterm births and conditions that can lead to type II diabetes among the Medicaid population in a 10-county area in the Delta.

The legislature appropriated $4,161,095 in the recent session for the project in Medicaid Division’s appropriation bill that was signed into law by Gov. Phil Bryant and goes into effect on July 1.

Revenue from sports betting dropped considerably in April after March Madness provided a boost last month.

Taxable revenue was just over $2 million in April as we enter a slow season for sports betting before football returns this fall. In March, revenues were just under $4.9 million, a far outlier from recent trends, thanks to the college basketball tournament. January and February hovered between $2.7 and $2.8 million.

Mississippi was the first state in the Southeastern Conference footprint to have legal sports betting after the Supreme Court overturned the federal ban, but neighbors are beginning to enter the sports betting world as well.

Louisiana is debating an on-again, off-again, and for right now, back on-again, sports betting legalization in casinos. While it’s a far ways from becoming law, this would have the biggest impact on Gulf Coast casinos, which provide a little more than half of the revenue for sports betting in Mississippi. For Mississippi’s Gulf Coast boosters, they have to be hoping this bill doesn’t make it across the finish line.

But the future of sports betting, if states want to increase tax revenue, appears to be online according to a new report from the Tax Policy Center, which has analyzed the first year of legal sports betting in the United States.

“As New Jersey demonstrated, allowing mobile sports betting in addition to in-person betting can exponentially increase tax revenue from sports gambling. Nevada and New Jersey were the only states to collect over $20 million in tax revenue over the past year from sports betting, and they are also the only states that offered online wagering throughout their states,” the Tax Policy Center writes.

Our neighbor to the north, Tennessee, has taken that approach by legalizing online sports betting. Unlike Mississippi and Louisiana, the Volunteer State does not have casinos. Therefore, those interested in betting on a sporting event will be able to do so from their smartphone or computer.

Betting in a casino may be attractive for a destination event such as the Super Bowl or a major boxing match, but it’s likely not going to happen for an average basketball or baseball wager on a Tuesday night. That person will continue to use an illegal, offshore website, which costs the state revenue it would otherwise receive.

And until Mississippi permits online betting, it will continue to lose that revenue.

A Mississippi shipyard that is receiving a $745 million contract from the federal government for a new class of three U.S. Coast Guard heavy icebreakers will be receiving $14 million in state incentives.

VT Halter Marine in Pascagoula will receive $12.5 million for a new drydock and $1.5 million for workforce training, according to the Mississippi Development Authority. The company says it’ll add about 900 workers and that adds up to about $15,555 per job.

The contract for engineering and design costs of the new icebreakers, along with long-lead time materials and construction costs was awarded on April 23. Construction on the first of three heavy icebreakers is scheduled to begin in 2021, with delivery on the first ship planned for 2024. If all of the options in the contract are realized, it could add up to $1.9 billion.

The icebreakers are desperately needed, as the Coast Guard’s lone remaining heavy icebreaker, the USCGC Polar Star, is overdue for replacement and is dealing with serious mechanical difficulties. The Coast Guard also has a medium icebreaker, the USCG Healy, that isn’t as capable an icebreaker as the Polar Star.

VT Halter has built most of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s fleet of research ships, missile boats for the Egyptian Navy, towed sonar array ships and accommodation barges for the U.S. Navy and landing ships for the U.S. Army.

VT Halter isn’t the only Mississippi shipyard receiving a handout from taxpayers despite lucrative U.S. Navy and Coast Guard contracts.

Since 2004, Huntington Ingalls Industries has received $307 million from state bonds to help fund improvements at its Pascagoula shipyard, which is one of the state’s largest employers with 11,000 workers and a construction contract backlog with the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard of $12.37 billion.

The company will receive another $45 million after the Legislature approved a payment in this year’s session.

The company received $45 million in 2017, $45 million in 2016 from state taxpayers, $20 million in 2015, $56 million in 2008, $56 million in 2005 and $40 million in 2004.

The Pascagoula yard builds the America and San Antonio classes of amphibious warfare ships, the Arleigh Burke class destroyers and the Coast Guard’s National Security Cutter, the Bertholf class.

Mississippi State University has been making headlines in recent weeks not only for their outstanding performance on the baseball diamond, but for the actions of one of their professors who some claim pushed blatantly leftist views on graded assignments.

Professor Michael Clifford was identified by academic watchdog group Campus Reform for providing questions on a Business Ethics exam which asserted moral judgements regarding CEO pay and suggested that Chick-Fil-A and Hobby Lobby practiced employment discrimination against LGBT applicants, without providing evidence to support the suggestion.

Clifford is also accused of ideological favoritism with the distribution of lower marks to those who disagreed with the premise of affirmative action or the data supporting the wage gap theory. One of Clifford’s former students told Campus Reform that he felt afraid to offer an opposing viewpoint in his classroom. “Shortly after I started the course in January, I heard from other students that he was very liberal and graded people based on whether they agreed with him or not,” Mississippi State student Adam Sabes, who is also a Campus Reform correspondent, said.

“Personally, this discouraged me from answering a question based on how I really feel and led me to answer tests or discussion board questions based on what the professor would like best as I needed a good grade in this class,” Sabes added.

This professorial behavior, while appearing unethical (which is rather ironic in a class on ethics), may not seem shocking to the average American if we were talking about Boulder or Berkeley. But this is a largely conservative university in an overwhelmingly conservative state, showing that the problems of bias in academia are not isolated to our nation’s coastal communities or famously liberal college towns.

Academia has become a complex game of inside baseball in recent decades where groups of ideologically aligned and motivated academics provide cover for one another as they actively pursue leftist or progressive viewpoints.

The evidence for this bias comes from Clifford himself. In response to Campus Reform’s reporting, he said that while he included the aforementioned questions that he also included others to choose from. This assertion isn’t a denial. It’s a premeditated cop out for any criticism of his bias.

Could you imagine what news outlets like CNN or MSNBC would say about a conservative professor who made statements offensive to the sensibility of the progressive academic class? Safe to say that they would be looking at some very tough days in the university faculty lounge.

It has unfortunately become the norm that we accept the liberal doctrine in our nation’s universities. Until we start calling out the bias, we’re going to continue to see colleges and universities remain the academic left’s own Animal House – without Dean Wormer to shut down their party.

In the meantime, I’m going to enjoy a delicious chicken sandwich from Chick-Fil-A, while there is still time

Lemonade Day 2019 is coming to the Golden Triangle. It’s a celebration that helps today’s youth become tomorrow’s entrepreneurs.

For generations, a summer tradition for boys and girls has been to make lemonade, set up a stand in front of their house or near a busy road, and earn money for that special toy they have been wanting, or maybe just to save for a future purchase. For a moment in time, children turn into entrepreneurs, even though they probably couldn’t tell you what the word means.

But lemonade stand entrepreneurs have met a force that strikes fear in the hearts of even the most seasoned professionals: the government regulator.

By now you have probably heard the stories, but they bear repeating because of the sheer lunacy of feeling the need to shut down a lemonade stand, and because they highlight the overcriminalization of our society thanks to laws we have adopted to fix every supposed issue or problem.

In California, the family a five-year-old girl received a letter from their city’s Finance Department saying that she needed a business license for her lemonade stand after a neighbor complained to the city. The girl received the letter four months after the sale, after she had already purchased a new bike with her lemonade stand money. The young girl wanted the bike to ride around her new neighborhood as her family had just moved.

In Colorado, three young boys, ages two to six, had their lemonade stand shut down by Denver police for operating without a proper permit. The boys were selling lemonade in hopes of raising money for Compassion International, an international child-advocacy ministry. But local vendors at a nearby festival didn’t like the competition and called the police to complain. When word of this interaction made news, the local Chick-Fil-A stepped up as you would expect from Chick-Fil-A. They allowed the boys to sell lemonade inside their restaurant, plus they donated 10 percent of their own lemonade profits that day to Compassion International.

In New York, the state Health Department shut down a lemonade stand run by a seven-year-old after vendors from a nearby county fair complained. Once again, they were threatened by a little boy undercutting their profits.

In response to these stories, the states of Utah and Texas have passed laws that allow children to operate occasional businesses, such as a lemonade stand, without a permit or license. Every other state, including Mississippi, should follow suit whether they have made the news or not.

As parents and as a society, we should be encouraging entrepreneurship. We should celebrate young boys and girls who want to make money, whether it’s for a new bike or to give to a ministry. When children have the right heart and the right ideas and are willing to take actions, we shouldn’t discourage it. The lessons are valuable. They learn that money comes from work, that you have to plan, and then produce a stand, signs, and lemonade. Introducing kids to the concepts of marketing, costs, customer service, and the profit motive is a good thing.

And why it has always been celebrated in our society for a long time.

Until today. But I suppose these interactions also provide these young children with another valuable but unfortunate lesson: beware of government and crony capitalism. Vendors who don’t like competition use the law to eliminate competition. And government, however good the intentions may have been, created the laws that actually work against the development of entrepreneurial values by regulating lemonade stands.

As often happens when government steps in to solve a problem, there are unintended consequences few are willing to acknowledge.

Hopefully, the absurdity of these stories has raised more than a few eyebrows. Perhaps they will cause people to recognize the downside of our regulatory burden and maybe even cause legislators to review more than a few of the laws, rules, and licensing regimes that are stifling growth, innovation, and capitalism. If we want a thriving and growing economy, we’ve got to have more entrepreneurs – including those future ones who sell lemonade in their neighborhoods today.

This column appeared in the Starkville Daily News on May 30, 2019.

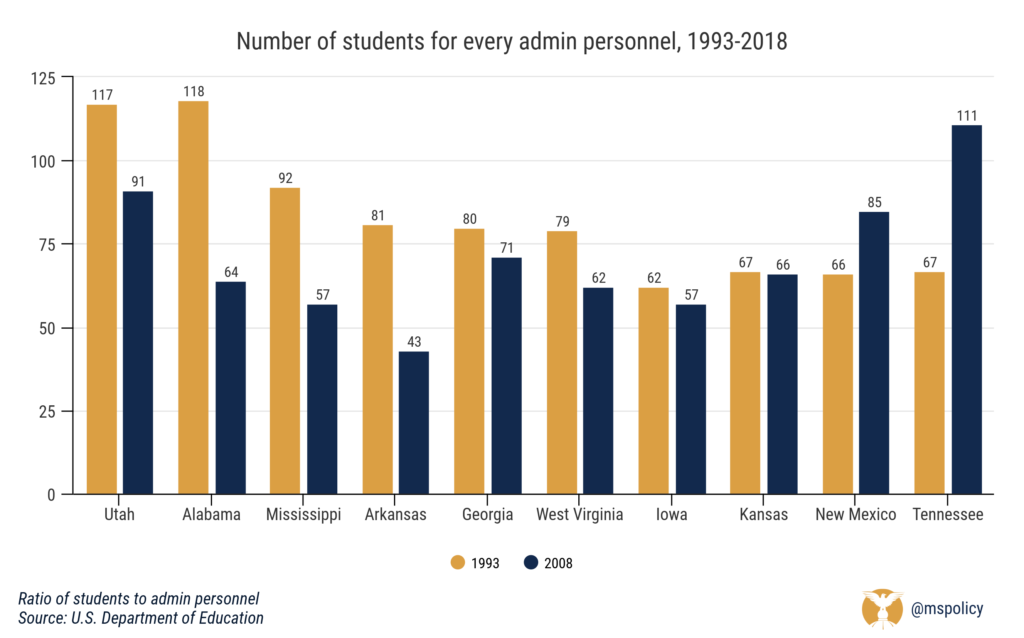

Mississippi was once better than the national average when it comes to students per each administrative employee in public K-12 schools, but now lags behind the national average.

According to an analysis of data from the National Center for Educational Statistics, the state had more students per administrative staffer (92:1) than the national average, 75:1, in 1993.

By 2018, the U.S. average was down to 63 students per administrative employee and Mississippi had fallen below that number at 57:1.

Administrative personnel are defined as school administrators (principals and assistant principals), district administrators and administrative support staff (both at the individual school and district levels).

The number of administrative personnel in Mississippi public schools increased by 51.1 percent from 1993 to 2018 while the inflation-adjusted spending on K-12 increased by 78.54 percent during the same span, according to data from the NCES.

According to the fiscal 2020 budget summary, $9.381 billion of the state’s $21.08 billion budget (44 percent) is from federal funds.

A useful exercise is to compare the growth of K-12 administrative staff in the Magnolia State with states with similar populations, with West Virginia included because of a similar rate of poverty. These states include:

| State | Population |

| Utah | 3,161,105 |

| Iowa | 3,156,145 |

| Arkansas | 3,013,825 |

| Mississippi | 2,986,530 |

| Kansas | 2,911,505 |

| New Mexico | 2,095,428 |

| West Virginia | 1,805,832 |

In 1993, Mississippi (92:1) had one of the nation’s smaller K-12 administrative states. This was better than states with far larger populations, including Florida (65 students per administrative employee), Tennessee (67:1) and Georgia (80:1). Only Alabama regionally (118 students per administrator) was better than Mississippi.

Arkansas was next best, with 81 students per staffer. Iowa was the worst, with 62 students per administrative staffer.

Fast forward to 2018 and the Mississippi’s growing K-12 administrative state (57:1) put the state near the back of the pack, worse than all but Arkansas and tied with Iowa. The Natural State had 43 students per every administrative staffer.

West Virginia had 62 students per administrative employee, while Alabama had 64 per staffer. Georgia (71 students per staffer) and Tennessee (111 students per administrator) were two of the best in the Southeast.

Florida was the worst regionally, with 40 students per administrator.

In 1993, K-12 spending from state, federal and local sources in Mississippi added up to $2,737,277,644, adjusted for inflation.

By 2018, that figure ballooned to $4,886,998,652, despite the number of students shrinking from 505,907 in 1993 to 470,668 in 2018.

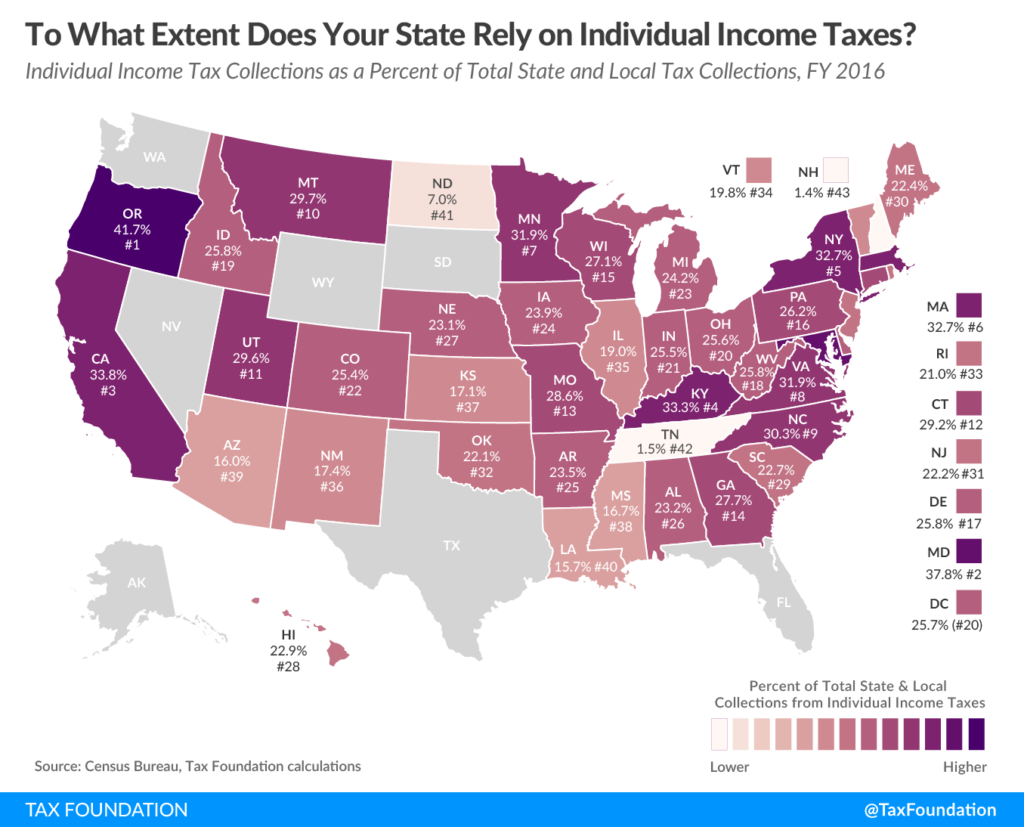

Individual income taxes account for 17 percent of Mississippi’s state and local tax collections.

That is one of the lowest percentages in the country among state’s that collect income taxes. According to the Tax Foundation, Mississippi came in at 38th lowest, behind just Arizona, Louisiana, and North Dakota.

Arkansas and Alabama were both middle-of-the-pack at 23.5 percent and 23.2 percent, respectively.

Oregon and Maryland relied most heavily on individual income taxes, at 41.7 and 37.8 percent, respectively. In Oregon’s defense, they do not charge a sales tax, contributing to the heavy reliance on income taxes.

Still, there is a better way to levy taxes. Mississippi should follow the model of neighboring Tennessee, which does not collect income taxes. (Tennessee does have a tax on investment income, known as the “Hall Tax,” but that will be fully repealed by 2021.)

Because how a state chooses to collect taxes has far-reaching implications. Income taxes tend to be more harmful to economic growth than sales taxes or property taxes. After all, sales and property taxes tax people on what they spend. Income taxes tax you on what you earn, either through labor or savings. Income taxes are also a less stable source of tax revenue, as individuals are more likely to experience more volatility with income than consumption.

Mississippi has begun the process of moving to a flat-income tax, with the phase out of the three percent tax bracket over several years. That is a good start. We have also debated legislation that would make recent graduates eligible to receive a rebate up to the full amount of their individual state income tax liability after they work in the state for five years. Essentially, Mississippi would be an income tax free state for a few years after graduation in an attempt to attract young talent to the Magnolia State.

That is a good thing. We should just expand it to everyone. By following the lead of high-growth, low-tax states in the Southeast that have lower taxes, lighter licensure and regulatory burdens, and a smaller government, we will be able to offer opportunities for people regardless of their age or their industry.

The executive director of Mississippi’s Medicaid program recommended to legislators that they should end state funding for a demonstration project run by the Delta Health Alliance.

Drew Synder, the executive director of the state Division of Medicaid, said in a December 28 letter to the legislature that that he’d “remain unable to endorse the (Mississippi Delta Medicaid Population Health Demonstration) project in its existing form as a cost-effective use of taxpayer dollars” despite speaking favorably about some of the people involved and the overall concept.

The Delta Health Alliance is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization that implements healthcare and education programs in the impoverished Delta region. It receives most of its money from taxpayers in the form of federal and state grants.

The project is supposed to use information technology to help providers reduce preterm births and conditions that can lead to type II diabetes among the Medicaid population in a 10-county area in the Delta.

Legislators ignored Synder’s advice and appropriated $4,161,095 for the project in Medicaid Division’s appropriation bill that was signed into law by Gov. Phil Bryant and goes into effect on July 1.

That’s on top of more than $10.6 million that’s been appropriated over the last four years.

- The appropriation bill for 2015 lists the demonstration project as one to receive state funds, but doesn’t specify how much will be spent on it.

- In 2016, the appropriation bill also didn’t specify the amount directed to the project, but also included $500,000 for a “patient-centered medical model home” in Leland, where the DHA is headquartered. The DHA’s tax form lists $1,376,231 in spending on the program for that year.

- The 2017 appropriation bill didn’t specify the amount for the project and included a $500,000 appropriation for the medical model home in Leland.

- The 2018 appropriations bill had $3,945,889 allocated to the project, with $2,879,051 to continue the existing program and $1,066,838 for the purpose of drawing matching federal funds. The bill also included another $500,000 for the medical model home.

According to an examination of records on the secretary of state’s website and DHA’s own tax forms, the organization hasn’t spent any money on lobbying the Legislature. State Rep. Willie Bailey (D-Greenville) is on the DHA board of directors.

According to the letter, the project has served only a few hundred beneficiaries and could be led by the managed care companies at a 76 percent federal match. He also said the project partially overlaps with an existing personal healthcare monitoring report program at the state Department of Health that’s funded already by DOM.

The letter also says that the project gives $80,000 per month to a health care information technology subcontractor for a predictive algorithm tool that hasn’t been utilized to find high-risk pregnant women for the study.

The DHA was created in 2001 as a collaboration by the five public universities led by former U.S. Sen. Thad Cochran to meet the healthcare and educational needs of the 18 counties in the Mississippi Delta region and funded by earmarks from the former chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee.

In 2017, DHA had $18,806,915 in revenue, primarily from federal and state funds and the group spent $19,340,337 for a deficit of $533,422. Among the $14,275,706 in government grants received by the organization in 2017 include:

- $5,642,945 in various grants from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- $3,284,675 from the U.S. Department of Education for the Indianola Promise Community.

- $3,114,998 from the Sunflower Childcare Coalition for early Headstart.

Program services accounted for $14,391,625 of those expenditures.

New emergency telemedicine regulations are good for healthcare, they are good for competition, and they are good for consumers.

Millionaire country music stars like to pretend they spend their weekdays driving a tractor and their weekends driving pretty girls down dirt roads in their pickup truck. While they can only dream, many Mississippians live the true country life in all its glory. It is a good life, but not as simple as the performers portray it to be. Living far away from population centers can mean reduced access to many essential services, like healthcare. Maintaining access to rural emergency medicine could be the difference between life and death for many Mississippians.

In Mississippi, there are 64.4 primary care physicians for every 100,000 residents, far below the national median of 90.8. Half of the Mississippi’s rural hospitals are in financial risk. Some have closed down completely, or shuttered critical services such as emergency rooms.

Rural emergency rooms are difficult to maintain. They must stay open 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The hospital has to hire several emergency room physicians to take turns covering those shifts. If those staff physicians cannot cover a shift, the hospital has to bring in a temporary physician – often from out of state. Not only is it expensive to staff an emergency room, it can be hard to recruit multiple emergency medicine physicians to live and work in a small town. Moreover, if a rural hospital does succeed in staffing an emergency department, it will see relatively few patients. Rather than bringing additional income to the hospital, it will likely cost the hospital money to operate.

Emergency telemedicine allows some small hospitals to keep their emergency rooms open, by staffing them with physician assistants and advanced practice registered nurses. When a patient arrives, an emergency medicine physician in another location – often a larger hospital – uses audio/visual technology and remote diagnostic tools to see the patient, and to instruct the nurse or physician’s assistant on the care that is needed. Some small hospitals choose to keep a physician in the emergency room, but use emergency telemedicine to provide an additional layer of expertise and consultation for their emergency department patients.

Despite the clear benefits of emergency telemedicine, its use in Mississippi has been limited. Current regulations prohibit physicians from providing emergency telemedicine services to small hospitals unless they worked at a Level One Hospital Trauma Center with helicopter support. Mississippi only has one Level One hospital in the state, so there has been no competition for this service. However, any physician who is board certified in emergency medicine is capable of providing emergency telemedicine services, and is able to transfer a patient by helicopter, regardless of the type of hospital the physician works for.

In short, the current regulations do not make sense, and prevent new providers from offering more options for emergency telemedicine. They are also vulnerable to a legal challenge, as they likely violate the due process and equal protection guarantees of the Mississippi and U.S. constitutions, and may violate federal antitrust laws.

One telemedicine provider that has been locked out of the emergency care market is T1 Telehealth located in Canton, Mississippi. T1 Telehealth was the state’s first private telemedicine company, and it developed a new model for emergency telemedicine that it believed would provide a better service for rural hospitals and patients. But it could not offer that new model due to the regulatory restrictions.

T1 Telehealth retained the Mississippi Justice Institute – a nonprofit constitutional litigation center that I work for – to challenge the emergency telemedicine regulations. After months of input and discussions with T1 Telehealth and other stakeholders, the Mississippi State Board of Medical Licensure has taken the right approach to make the regulations fair and to increase access to healthcare. New proposed regulations have been adopted that will allow any licensed emergency medicine physician to offer emergency telemedicine services in Mississippi.

The new proposed regulations will be reviewed by the Occupational Licensing Review Commission before becoming final. Approval by the commission seems assured, as it is chaired by Gov. Phil Bryant, who has been a tireless champion of expanding telemedicine in Mississippi and a strong supporter of efforts to reform the state’s anticompetitive emergency telemedicine regulations.

The new regulations will be a great development, not just for T1 Telehealth, but for all telemedicine providers, for small rural hospitals that rely on telemedicine, and for patients across Mississippi. Competition encourages innovation, more options, better services, and lower prices. All things that will make rural healthcare and Mississippi country living that much better.

This column appeared in the Clarion Ledger on May 29, 2019.