Two years ago, the National Association of Charter School Authorizers (NASCA) gave Mississippi the eighth highest score on their policy analysis of state charter laws. At the same time, Arizona came in at just 18th.

In the eyes of organizations like NASCA and others, states like Arizona do not have the necessary regulations in place concerning key issues like renewal standards, academic performance, or a default closure provision. And they don’t perform authorizer evaluations.

Mississippi took a different approach and developed a “model” charter law that was based on best practices from NASCA and similar organizations. But as we have seen, charters have been slow to open in Mississippi. Not because of lack of interest among operators or parents, but because of the process of authorizing charter schools in Mississippi.

This year, 16 different operators proposed opening a total of 17 schools across the state.The prior two years, 18 operators filed similar letters of intent to begin the charter school application process. Yet just five schools are currently opened for this school year, with one more coming in 2019.

Arizona, on the other hand, has approximately 600 schools serving north of 185,000 students. That accounts for about 20 percent of public school enrollment in the state. Deemed the “wild west” by detractors, over the past five years some 200 schools have opened with about 100 closing. Those numbers aren’t because of a law, either for better or for worse. But because parents in Arizona now recognize that they are empowered to choose the right school for their child.

Administrative attempts to shut down a public school, regardless of how poor it is doing on test scores or other measures we commonly look at, is not an easy task. You are usually met with a fierce opposition of loyal parents and potentially lawsuits as well. For the most part, Arizona parents have moved beyond that.

They move on. It is parents who are now closing poor performing schools, not the government. Of those schools that closed, they were open on average just four years (even with a 15 year reauthorization window) and had only 62 students their final year. Without government intervention, parents were able to determine what wasn’t working.

We shy away from using words like “market” when it comes to education, but that is exactly what is happening. After all, parents have the ability to make a choice.

So it’s a different model, but how is it working? After all, our focus should be outcomes and not intention.

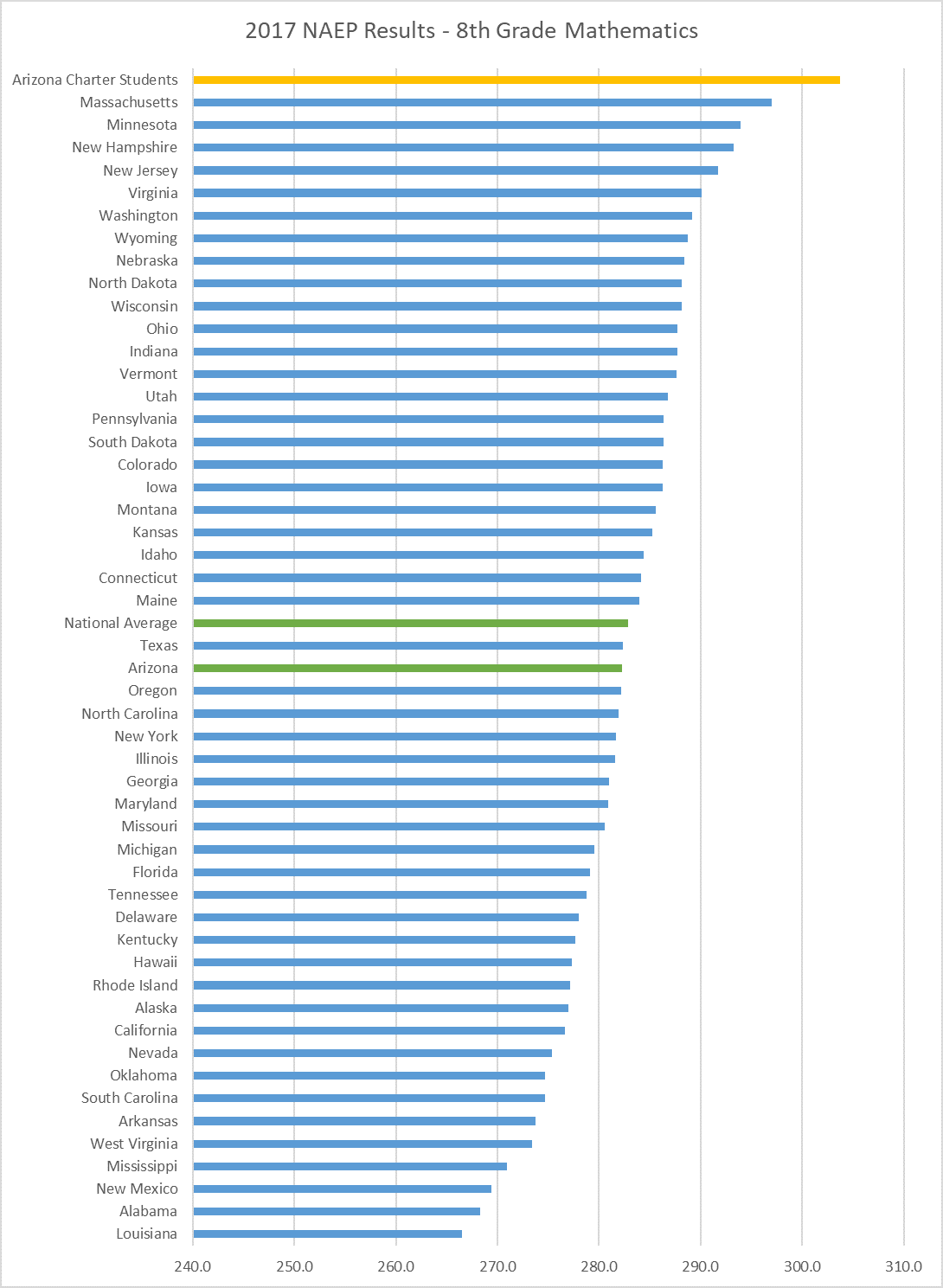

A review of the most recent NAEP scores among Arizona’s charter students helps to answer that question.

Beyond the overall numbers, perhaps more newsworthy, Arizona charter schools have also boosted the largest gains in the country over the past eight years among all four tests. No state showed more progress in terms of points gain between 2009 and 2017 (when Arizona charter schools are compared to the 50 individual states).

A couple other important points to make. While Arizona’s 8th grade students are competing with a traditional top-performing state like Massachusetts, the similarities stop there. Arizona is educating a high-minority population while Massachusetts (and similar states) are largely white. At the same time, Arizona spends about half of what Massachusetts spends per student.

Today, 84 percent of zip codes in Arizona have a charter school, the highest percentage in the country. Mississippi’s new to the charter game so it’s not a fair comparison. But that number is a rounding error in the state.

By making options available in large numbers, also known as supply, and giving power to choose to parents, also known as demand, we see a successful bottom-up accountability system.