In an age increasingly expanding its reliance on technology in business, science, education, and defense, the significance of a technologically skilled workforce has never been more important.

While many states have made great strides in the tech sector, the Mississippi economy is in need of more tech expertise. Whether this expertise is utilized in the state’s more traditional industries, such as manufacturing and agriculture, or used to launch innovative new startups, tech skills are essential.

I recently visited with Mike Forster, chairman of the nonprofit Mississippi Coding Academies, based in Jackson and Starkville. It was an excellent opportunity to learn more about the work being done there to develop a skilled workforce in Mississippi.

Matthew: What is the main purpose of the Mississippi Coding Academies?

“Mississippi has done a great job in the past attracting manufacturing industries to our state. But the future of this state and of this nation … in fact, the hub of the world economy, is the digital economy. Everything that we touch every day, from literally our refrigerators and televisions to our smartphones, requires software development. Coding is what puts life in all of these electronic devices.

“So we, the founders of the Mississippi Coding Academies, perceived that there was a need in Mississippi to directly address the underserved population of our state who don't have some of the advantages others might: others who can go to four-year colleges and make an investment in computer science as a choice of degree and therefore prepare themselves for futures in this industry. The interesting thing is that the four-year colleges in Mississippi produce about 250 to 300 computer science graduates a year, and half of them leave the state. We've got about a thousand openings right now in the state for people with the kinds of skills that Mississippi Coding Academies produce. Some of those jobs are for more experienced people, of course, but the message is still the same.

“There is a big gap between what we have in terms of local production of people who have the ability to develop software for electronic devices and for new services. There's a huge gap in the state between what is needed and what we're producing. The community colleges play an important role here. I don't want to overlook them, but we are unique in that we are really a high tech vo-tech operation. We focus on folks who are high school graduates, who typically have no ability for whatever reason, socioeconomic or whatever, to go to college, even to a community college, or, perhaps, they just are people in transition. Perhaps they're veterans who've served this country, and now they're looking for a way to build some new skills.

“And so what we do is take our students – and we don’t prepare them for jobs – we prepare them for careers. This is a 20-year or 30-year career opportunity. Now they're going to have to continue to develop, change and grow, but they've got all the fundamentals when they leave us to be able to have a long-term career in this economy.”

Matthew: Can you tell us a little bit about the significance of encouraging people with different career contexts to learn code?

“I spent 54 years in the technology world, and I ran worldwide operations for billion-dollar companies and was CEO of two “bleeding edge” software companies. One of the things I learned over the course of all that time is you cannot predict who has the skills to be a good software developer. There is a creative component, as well as an analytical component, to this job. And the most capable and creative developers that ever worked for me had other skills, but they also had a certain level of analytical ability and they could tie those two things together. You just don't know who has those skills. They are innate in many, many people who don't even realize they have it. Our coders are layering these new skills onto existing skills and going forward. … Part of what we do is conduct a little bootcamp, and we let them learn more about what it is we are expecting from them. They invest a year of their lives in developing these skills. When they get through, they are ready to go to work. They have been in a workplace environment. It is as if they had just spent a year in a training program with a local employer, except that they've been in this simulated workplace in the coding academy.”

Matthew: How do you work with potential future employers?

“One of the unique things that is a very important part of our program is that we build partnerships with employers. They make sure our curriculum is up to date, they evaluate our students. They help us select our students. They come in multiple times a year. Some of them are guest lecturers, but they all bring the practical, ‘Here's what it takes to be successful in business,’ type thinking into the Coding Academy. These employers and these supporters add tremendously to what it is we're doing because they put us in a real-world type environment.

“Neither Jackson nor our GTR Academy [in Starkville/Columbus] are lecture halls, they are a workspace. Now we'll use whiteboards and screens to teach a new concept, or to get a new concept going, but what we do is basically introduce a concept and put people to work. They learn by doing. They work together. They learn to work together in small teams. And one of the things that this employer relationship provides is to keep us on our toes. It keeps us current. This industry reinvents itself about every two years: there's some new development in technology that didn't exist two years before. Because we can be light on our feet, we can operate a little bit more independently than educational institutions. We can adapt quickly to what's going on, and that's critical in preparing our students for the workforce with future employers.”

Matthew: How are the Coding Academies facilitating the further development of Mississippi’s largest current industries, as well as new industries?

“There is no industry today that does not need technology. You can take an industry as traditional as steel, or the energy sector, or Mississippi’s tire plants. These manufacturers have enormous amounts of data. Our graduates can help industries that are more traditional. Manufacturers need significant amounts of tech expertise too, to be able to harvest and to use all the data they're collecting. They all need technology. Of course, tech startups need coding too, as does everything associated with the digital economy.

“The net of it is that there's no industry that doesn't need traditional IT support, help desk support, data, mining, cyber security and reporting capabilities, as well as application development for new capabilities and functionality on the shop floor. All those kinds of things are needed and are essential. Our graduates are able to fill those types of jobs.”

Matthew: Why is Mississippi a good place for tech innovation?

“Some of Mississippi’s advantages are that we've got a low cost of living and our students have a strong work ethic. And many of them have the skills to become 21st century economy contributors. Our public schools need to do more to inject coding into their junior and senior high programs. As they do, we will have more and more students ‘self-select’ themselves to be candidates for the coding academies, or to pursue a traditional computer science degree. We need to expand our coverage within the state, and I’m excited about the possibilities of a Gulf Coast location in the near future. We’ve also got an exciting new initiative called ‘TechSmart’ that will allow us to reach smaller communities via tele-learning. Governor Tate Reeves and the key folks at the Mississippi Development Authority and the State Workforce Investment Board are all very supportive of our efforts, so my confidence is at an all-time high that we’ll continue to expand and provide these 21st century skills to Mississippi’s greatest natural resource: our wonderful people.”

The education setting for many children in Mississippi shifted this year. Perhaps the numbers weren’t as dramatic as mid-summer polling indicated, but the number of homeschoolers has increased by 35 percent over the previous year.

According to unofficial data collected by the Mississippi Department of Education, 25,376 students are homeschooling this year. These numbers aren’t final and may increase. Families are required to submit a certificate of enrollment form for each child who is homeschooled by September 15. Generally, families don’t submit forms for kindergarteners because compulsory education in Mississippi begins at 6.

For the previous school year, there were 18,904 homeschoolers. Homeschooling now makes up about 5 percent of total student enrollment.

The relative ease of homeschooling has helped many families who had never considered homeschooling get started. For a state that has generally shown little interest in education freedom, the freedom to homeschool is broadly supported and protected by law. The one thing a parent must do is file an annual certificate of enrollment with your local school district’s school attendance officer. All you need on the form is your child’s name, address, phone number, and a simple description of the program such as, “age appropriate curriculum.”

When you do that, your child and you are now exempt from the state’s punitive compulsory education laws. There are no requirements on curriculum or testing or who can teach. Parents, instead, have the freedom to choose the educational system, style, and setting that works best for them and their children.

The Department of Education “recommends” parents review state curriculum guidelines and maintain a portfolio of their child’s work, thought that is not required. As opposed to following a government curriculum that tells your child what he or she must learn at what age, homeschooling allows you to let your child learn at their own pace.

That means a child who is excelling can move forward at a quicker pace, cover additional topics, or take in material at a deeper level. If a child is struggling, you can slow down, switch your teaching style, or bring in new materials. If your child has a unique interest, the world is literally at their fingertips with scores of free, online training materials. Yes, YouTube is filled with funny cat videos. But it also provides a library of instruction on virtually any topic you can think of.

Thanks to today’s technology, a quick Google search can help you get more comfortable with homeschooling. There is an abundance of homeschool Facebook groups with veterans who are willing to share their ideas on getting started, curriculum, extracurricular activities, maintaining your sanity, and much more. Connection to these groups is also a venue to plan an endless variety of outings and field trips. It won’t take long to realize your child will receive as much “socialization” as you would like.

There are also options such as co-ops, where families gather together and share teaching responsibilities among parents. Similarly, we have seen the emergence of microschools this year in which a small group of parents pool their resources together to hire a teacher.

While homeschooling experienced it's biggest one-year jump ever, the number of students attending government schools fell from just under 466,000 last year to 442,000, a drop of over 5 percent. This is the eighth straight year that enrollment has decreased since a peak of almost 493,000 for the 2012-2013 school year.

Mississippians, like all Americans, are buying more guns now than ever before. There was a sharp increase at the beginning of the pandemic and if trends are any indication, those numbers will only go up with a new Democratic administration.

According to NICS data, more than 32 million background checks have been conducted this year. The year prior, there were about 28 million background checks – which was a record at the time. But it would only last a year.

In Mississippi, there were 27,815 checks in October. A year ago, that number stood at 19,167. Going back to the beginning of the pandemic in March, there were 33,000 background checks completed in Mississippi compared to about 23,000 in 2019.

And a large chunk of this is first time buyers.

"Retailers reported an increased number of first-time gun buyers, estimating that 40 percent of their sales were to this group," the National Shooting Sports Foundation announced in early June. "This is an increase of 67 percent over the annual average of 24-percent first-time gun buyers that retailers have reported in the past."

A year ago, Michael Bloomberg, one of the most infamous (and wealthiest) gun control advocates in the country, said that members of a church should not carry guns and defend other members as happened last year. Rather, we should wait for law enforcement.

That comment didn’t age well.

That is why we saw uncommon spikes this summer in the midst of riots and looting across the country. In June there were 3.9 million background checks nationwide. An increase from 2.3 million the year prior. If law enforcement is unable – or in some cases unwilling – to protect your property, residents are doing it. As they should.

Because regardless of who the president is or if a city council that wants to ban gun shows, Americans will continue to own guns and purchase new guns when they feel it is necessary.

Enrollment at Ole Miss is down for the fourth year in a row according to new data from the Institutions of Higher Learning.

Ole Miss had an enrollment of 18,668 for the fall of 2020, compared to 19,421 last year. This represents a drop of 3.9 percent. When the University of Mississippi Medical Center enrollment is included, total enrollment for the University of Mississippi system increases to 21,676, but that is still down 2.7 percent from last year.

Total enrollment for Mississippi’s eight public universities is 77,154, down from 77,894 a year ago. That represents a continued trend more than a newfound fear because of a virus, indicating that families aren’t particularly worried about sending their children to college. From 2018 to 2019, enrollment dropped by about 1.5 percent.

Enrollment is up at two universities in the state. Mississippi State saw an increase of 3.4 percent to 22,986. (Mississippi State is now larger than the total University of Mississippi enrollment.) The University of South Mississippi saw an increase of 3.3 percent to 14,606.

The five other public universities each experienced declines, some more dramatic than others. Delta State lost more than 20 percent of its students, a decline of more than 700 on the campus that now has fewer than 3,000 students and is no longer the fifth largest university in the state.

| University | Fall 2019 enrollment | Fall 2020 enrollment | Number change | Percent change |

| Alcorn State | 3,523 | 3,230 | -293 | -8.3% |

| Delta State | 3,761 | 2,999 | -762 | -20.3% |

| Jackson State | 7,020 | 6,921 | -99 | -1.4% |

| Miss. State | 22,226 | 22,986 | 760 | 3.4% |

| MUW | 2,811 | 2,704 | -107 | -3.8% |

| MVSU | 2,147 | 2,032 | -115 | -5.4% |

| Ole Miss* | 22,273 | 21,676 | -597 | -2.7% |

| Southern Miss | 14,133 | 14,606 | 473 | 3.3% |

* Includes both the University of Mississippi and UMMC.

Mississippi Valley State University remains the smallest university in the state at 2,032 students after seeing enrollment decline by 5.4 percent this year.

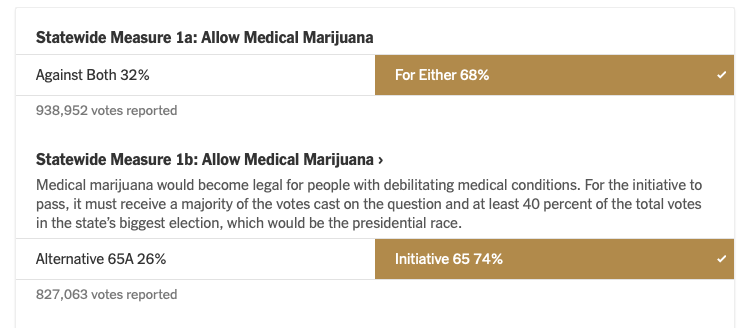

Mississippi voters overwhelmingly approved a medical marijuana ballot initiative on Tuesday while rejecting the more restrictive measure from the legislature. Mississippi will soon become the 35th state with a medical marijuana program.

With over 60 percent of the vote in Wednesday morning, 74 percent of voters chose Initiative 65, the citizen-sponsored ballot initiative. This was the second part of a two-step process because of the legislative alternative. In the first question, 68 percent said “for either.” If a majority had said “against both,” the initiative would have died regardless of the second question.

As written in the initiative, the Mississippi Department of Health will be responsible for developing regulations for the program by July 1, 2021. Medical marijuana patient cards will need to be issued by August 15, 2021.

Here is how the process will work.

Step 1

A person must have a debilitating medical condition. The term “debilitating medical condition” is defined in the proposal as one of 22 named diseases, plus there is a special allowance for a physician to certify medical marijuana for a similar diagnosis.

Some of those conditions include:

- Cancer

- Epilepsy and other seizure-related ailments

- Huntington’s disease

- Multiple sclerosis

- Post-traumatic stress disorder

- HIV

- AIDS

- Chronic pain

- ALS

- Glaucoma

- Chrohn’s disease

- Sickle cell anemia

- Autism with aggressive or self-harming behavior

- Spinal cord injuries

Step 2

A person with a debilitating medical condition is examined in-person and in Mississippi by a physician. The term “physician” is defined in the proposal as a Mississippi-licensed M.D. or D.O.

If the physician concludes that a person suffers from a debilitating medical condition and that the use of medical marijuana may mitigate the symptoms or effects of the condition, the physician may certify the person to use medical marijuana by issuing a form as prescribed by the Mississippi Board of Health.

The issuance of this form is defined in the proposal as a “physician certification” and is valid for 12 months, unless the physician specifies a shorter period of time.

Step 3

A person with a debilitating medical condition who has been issued a physician certification becomes a qualified patient under the proposal.

Step 4

A qualified patient then presents the physician certification to the Mississippi Department of Health and is issued a medical marijuana identification card.

The ID card allows the patient to obtain medical marijuana from a licensed and regulated treatment center and protects the patient from civil and/or criminal sanctions in the event the patient is confronted by law enforcement officers.

“Shopping” among multiple treatment centers is prevented through the use of a real-time database and online access system maintained by the Mississippi Department of Health.

Medical Marijuana Treatment Centers will be registered with, licensed, and regulated by the Mississippi Department of Health. Each medical marijuana business will have to apply to and be approved by MDH. But there will not be a limit on the number of businesses, allowing for a free market based on demand.

Users would not be able to smoke medical marijuana in a public place and home grow would be prohibited, though it is legal is some other states.

Mississippi voters who haven’t already cast absentee ballots head to the polls tomorrow to vote for numerous offices and initiatives.

At the top of the ticket, Mississippians will be choosing from President Donald Trump, former Vice President Joe Biden, and seven other candidates, including Kanye West, for president. In 2016, Mississippi gave Trump 58 percent of the vote. Mississippi last voted for a Democratic presidential candidate in 1976.

Mississippians will also be voting in a rematch for United States Senator. Two years ago, Cindy Hyde-Smith, who had been appointed earlier in the year by then-Gov. Phil Bryant, defeated former Congressman Mike Espy 54-46. That was to fill the remainder of former Sen. Thad Cochran’s term. Hyde-Smith is vying for a full six-year term Tuesday. Hyde-Smith and Espy will match up again, along with Libertarian Jimmy Edwards.

Only Rep. Steven Palazzo is unopposed for re-election in South Mississippi among Mississippi’s four Congressional seats. Rep. Trent Kelly faces Democrat Antonia Eliason. Rep. Bennie Thompson faces Republican Brian Flowers. And Rep. Michael Guest meets Democrat Dorothy Beneford.

Two of the four Supreme Court justices on the ballot have opposition this year. Justice Kenny Griffis was appointed to the Court in 2018 and faces Latrice Westbrooks in the nonpartisan election. This district, officially District 1, covers central Mississippi, ranging from Republican suburbs of Rankin and Madison counties to Democratic strongholds of Hinds county, along with much of the Delta. While the positions are officially non-partisan, much of the Republican establishment and aligned-business groups have backed Griffis, while most Democrats, including Thompson, are supporting Westbrook in the slightly Democratic district.

In the Northern District, Justice Josiah Coleman faces Percy Lynchard for the District 3 seat. Leslie King is unopposed for another seat in District 1, while Mike Randolph is unopposed in District 2, the southern district.

Mississippians will also see three questions.

The first question, which has garnered the most attention, is a ballot initiative to make Mississippi the 35th state to adopt medical marijuana. Last spring, the legislature put an alternative on the ballot, which makes this a two-part question. The first question will ask if you want either. It's an either or neither proposition. If a majority say neither, the second question doesn't matter. If a majority says either, then whichever option (the original ballot initiative or the alternative) receives a majority is enacted, provided it receives at least 40 percent of the ballots cast.

The second measure removes the electoral vote requirement for statewide elections. Right now, the state House votes on the governor if a candidate does not receive a majority of the vote and majority of legislative districts. If enacted, this removes that requirement and would move to a runoff system between the top two vote getters if no one receives a majority.

The final measure is adoption of the new state flag. This summer the legislature took up the issue, removed the current flag, and a commission created a new flag for voters to vote on. If a majority vote against it, a new flag option would be designed and vote upon in 2021.

According to the Secretary of State, you will not need to wear a mask to enter a polling place.

While many warnings have been issued about trick-or-treating during a pandemic, it appears that decision will remain with families in most Mississippi cities. But even with the green light to go door-to-door, children may unknowingly run afoul with existing local laws.

These aren’t laws restricting criminal actions often associated with Halloween mischief, such as egging a house or smashing pumpkins that belong to someone else. Rather, these are restrictions on who can trick-or-treat, how late they can be out, and what they can or can’t wear.

A story on Roanoke, Virginia’s trick-or-treating laws went viral last year. In Roanoke, no one over 12 is allowed to trick-or-treat. Not only is it illegal, it is a misdemeanor punishable by up to six months in jail.

While the potential jail time might not apply, the city of Meridian also prohibits those over 12 from asking for candy. “It shall be unlawful for any person to appear on the streets, highways, public homes, private homes, or public places in the city to make trick or treat visitations; except, that this section shall not apply to children 12 years old and under on Halloween night,” the ordinance reads. And you have to be inside by 8 p.m.

Throughout the country, towns like Belville, Illinois, Bishopville, South Carolina, and Boonsboro, Maryland have similar age limits.

In the year of mandated face covernings, Meridian also restricts anyone over 12 from wearing a mask or any other disguise, unless they get a permission slip from the mayor or chief of police. Dublin, Georgia and Walnut Creek, California have similar mask restrictions.

The rest of your costume may also be illegal in some locales. In Alabama, it’s illegal to dress up as a minister, priest, nun, or any other member of clergy. Violators can be slapped with a $500 fine and a year in jail.

In a recent move that received national attention, the Kemper County Board of Supervisors approved a measure in 2016 that made it illegal for anyone to appear in public in a clown costume or clown makeup for Halloween that year. The ordinance expired the day after Halloween. That ordinance carried a fine of $150 for outlaws who wore clown costumes.

The conventional wisdom is that these ordinances aren’t enforced. Police aren’t asking boys who are starting to show signs of facial hair for identification to check their age. Chances are no one is spending 365 days in a county jail in Alabama for impersonating a priest or rabbi.

Which, of course, leads to the next question: Why have such laws? We already have laws on the books to restrict actual criminal activity. We don’t need additional laws that are confusing and do little but potentially ruin a fun night for millions of children.

We simply have too many laws in this country. It should not be government’s responsibility to regulate the behavior of children on a Halloween night running through the neighborhood in pursuit of treats. That responsibility belongs to the parents, just like it should on every other night of the year.

We know the world changes around us on a regular basis. We can order anything we want on our phone and have it delivered to our front door. Well, except for alcohol. We can use that same phone to catch a ride, rather than having to rely on a government monopoly for service.

These are just a couple of the more obvious and more recent changes. But it is up to us to adapt and keep up, and for most of human history we’ve done a pretty good job at that.

So, what has been holding us back? Usually the government, and our permission-based society. This became all the more relevant and all the more noticeable at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Think back to two pressing needs at the time: face masks and hand sanitizer. Empty shelves dotted grocery store aisles. Obviously demand increased, but the private sector can adapt. What was the hold up? Government, specifically the Food and Drug Administration.

Distilleries wanted to produce hand sanitizer, something that makes a lot of sense, but they faced a maze of local and federal regulations before they could begin. And if you want to make a face mask, you must first go through the FDA’s approval process, which can take months. In both cases, the regulations were eased, and manufacturers were allowed to ratchet up production.

But should these and many of our regulations exist in the first place? Yes, we need safety, but we can’t be so inflexible that government red tape blocks production on a needed item during a pandemic. That’s obvious, but there are plenty of other areas where government does not allow us to adapt and does not allow entrepreneurs to put their skills to use.

That is why we need to shift from a permission-based society to a default of permissionless innovation. And it is something we can do in Mississippi, a state that has long trailed the rest of the country when it comes to economic growth. Because too often, government creates the framework, a few enter that field, and then “capture” regulators to make it more difficult for new entrants or technology.

The sharing economy is a great example of this. For decades, government approved taxicabs had a monopoly on the service they provided. They encouraged regulations and worked with local governments to create them. Then ridesharing companies were launched and all of a sudden, they had competition. And the outdated model couldn’t compete with prices, availability, and overall service. Naturally, they went back to government to restrict Uber and Lyft. And local governments like Oxford were happy to comply.

After all, these new people didn’t come to us for permission.

So how can we change that and why is this necessary?

COVID-19 impacted more than our ability to purchase face masks or hand sanitizer. Our education systems, restaurants, retail, airlines, and hospitals have all undergone changes to their business model because of the pandemic. We as a state should be encouraging their innovation, rather than placing roadblocks.

An industry neutral regulatory sandbox offers an opportunity for these businesses to navigate around, and temporarily suspend, problematic rules and regulations, allowing businesses to adapt and compete, based on their own ability and market response rather than their ability to win favor from politicians.

And we need to do this before everyone else.

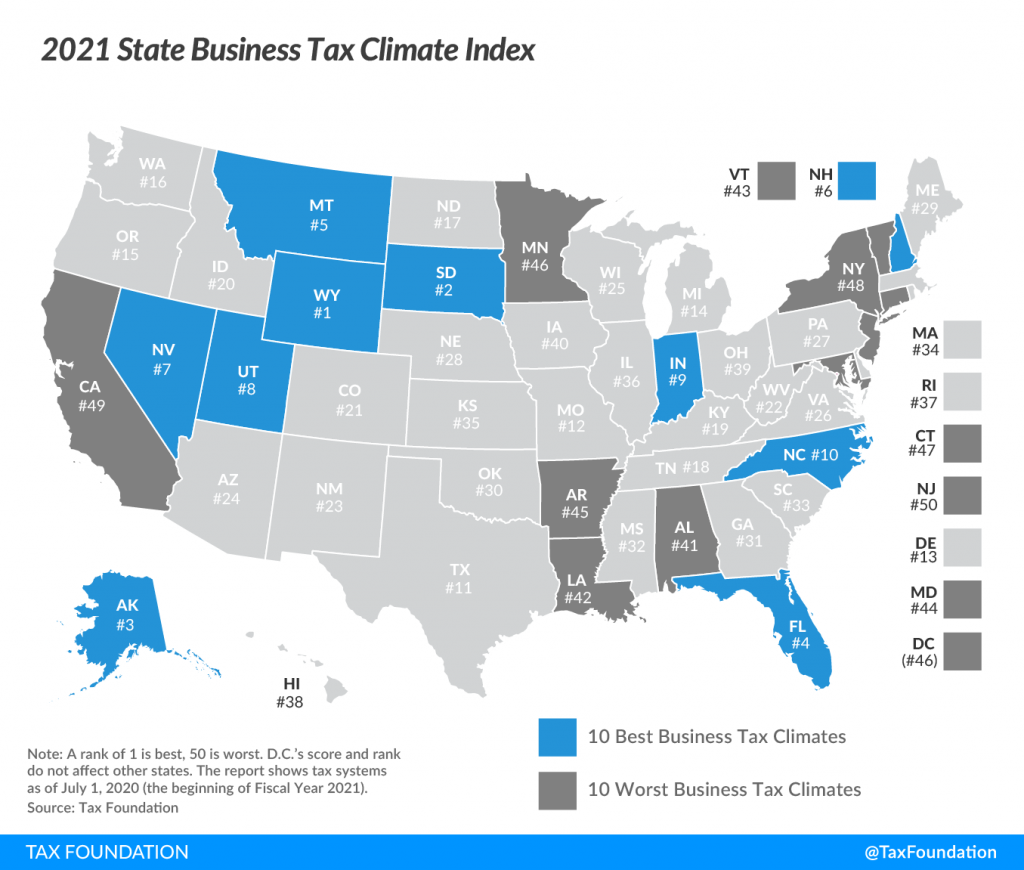

Mississippi’s business tax climate dipped slightly last year as it remains in the bottom half nationally.

The Tax Foundation placed Mississippi 32nd overall for taxes, including corporate, individual, sales, property, and unemployment insurance taxes. The only neighboring state to do better was Tennessee. Alabama, Louisiana, and Arkansas were rated 41, 42, and 45 respectively.

The top five states remained the same. Wyoming was again the top-rated state, followed by South Dakota, Alaska, Florida, and Montana. Not surprisingly, the bottom five states were New Jersey, California, New York, Connecticut, and Minnesota.

“Business taxes affect business decisions, job creation and retention, plant location, competitiveness, the transparency of the tax system, and the long-term health of a state’s economy,” the report noted. “Most importantly, taxes diminish profits. If taxes take a larger portion of profits, that cost is passed along to either consumers (through higher prices), employees (through lower wages or fewer jobs), or shareholders (through lower dividends or share value), or some combination of the above. Thus, a state with lower tax costs will be more attractive to business investment and more likely to experience economic growth.”

Mississippi dropped a spot from last year, not because the tax climate in Mississippi has worsened, but because other states have improved.

The state received its best marks for unemployment taxes (5th best) and corporate taxes (13th best). The corporate tax component measures impacts of states’ major taxes on business activities, both corporate income and gross receipts taxes. The unemployment insurance tax component measures the impact of state UI tax attributes, from schedules to charging methods, on businesses.

Mississippi’s worst tax categories were property and sales. It would be a good idea to lower our business tax burden on land, buildings, equipment, and inventory.

Mississippi’s business tax climate is part of the reason the state relies so heavily on corporate welfare for enticing businesses. Instead of offering taxpayer incentives or tax abatements to select companies, the state should begin the process of improving the tax climate for all businesses rather than just those who curry political favor.