The consequence is more limited access to diverse food options for families, students, hospital patients, restaurateurs and chefs.

More specifically, Mississippi Department of Agriculture (MDAC) regulations prohibit all but direct farm-to-consumer sales by small-scale poultry producers. This is contrary to Mississippi law, which has adopted a federal exemption that allows small producers to sell to grocery stores, restaurants, hotels, hospitals and other institutions.

In conformity with federal law, Mississippi law technically incorporates the federal 20,000 bird exemption, which allows poultry producers who raise fewer than 20,000 birds a calendar year to sell these birds without being subject to daily inspection and other facility requirements. MDAC regulations, however, do not recognize this mandated exemption in any meaningful way.[1]

This means that Mississippi is forcing small poultry producers to follow federal requirements that were drafted with large-scale producers in mind. These requirements are onerous and expensive and address the unique problems created by large-scale poultry production.[2] It is not appropriate to subject small producers to these requirements, which is why federal law has always allowed for a small producer (20,000 bird) exemption. Unlike other states that recognize the federal 20,000 bird exemption, Mississippi prohibits all but direct farm-to-consumer sales for small farmers. This completely undermines the purpose of the exemption. Mississippi agricultural regulations ban small producers from selling to restaurants, grocery stores, hotels, schools and hospitals. As a result, small poultry producers are denied access to distribution channels currently open to large producers.

State law should clearly define what a small-scale producer is (consistent with the federal definition of a 20,000 bird producer) and clarify that these producers are not subject to the same inspection requirements that large producers operate under. In particular, state law should clarify that small producers are not subject to mandatory daily inspection and other facility requirements. State law should also clarify that small producers may sell to restaurants, grocery stores, hotels, schools and hospitals. Alternatively, MDAC could issue new rules that actually conform to the federal 20,000 bird exemption and thus rectify the current contradiction between state law and agency regulatory practice.

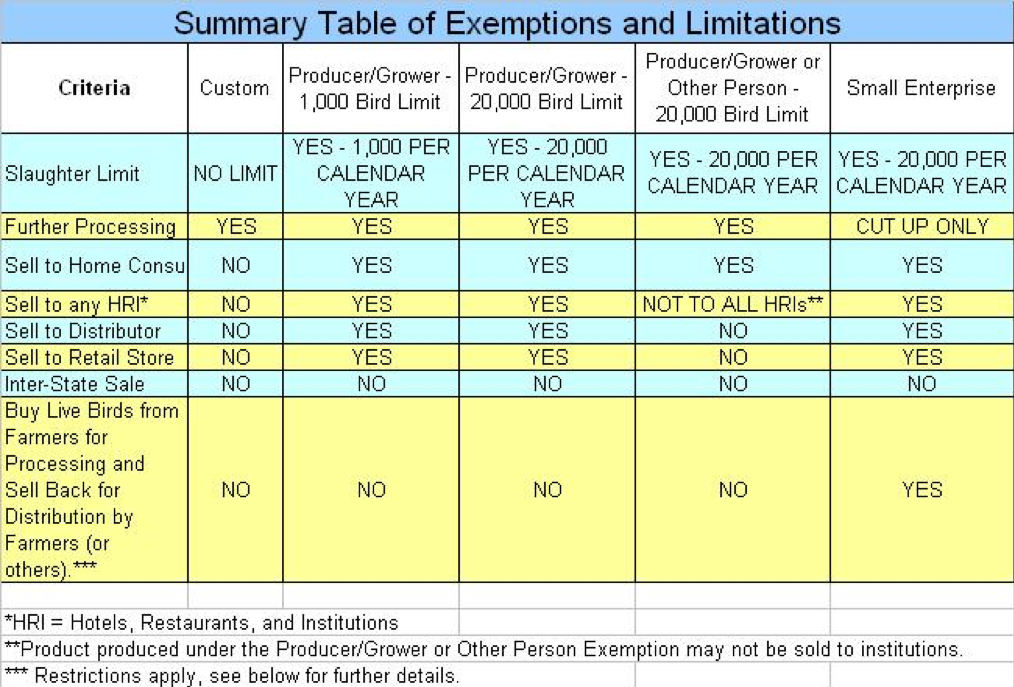

More than 40 states have adopted the 20,000 bird federal exemption. Granted, not all of these states are actually implementing the full range of federal exemptions. In neighboring Alabama, for instance, farmers with the exemption may only sell in farmer’s markets, as well as direct from the farm. Louisiana, on the other hand, has fully implemented the 20,000 bird exemption and allows sales to retail outlets, restaurants and various institutions. Louisiana has also adopted the federal small enterprise exemption pertaining to the processing of dressed exempt poultry (see table below).

North Carolina stands out as one of the states with the best and clearest regulatory guidance. Their policy allows for the slaughter, processing and distribution of poultry without mandatory daily inspection. The regulations also spell out requirements aimed at protecting consumer health and safety. These include: sanitary standards and practices, detailed recordkeeping, and mandatory labelling that identifies the processor and provides for safe handling instructions. These requirements essentially follow federal law.

North Carolina’s deregulation of small poultry producers has been a win-win for both small and large producers. The market for each of these products is different. For many consumers seeking farm-fresh chicken, the choice is not between purchasing small-scale or large-scale produced products. The choice is between purchasing small-scale produced chicken or no chicken at all.

North Carolina’s example is illustrative. While the state has more than 1,000 small-scale producers, Sanderson Farms recently opened a plant with the capacity to slaughter and process 1.25 million birds a week. Consider that Sanderson Farms’ stock has increased many times over, going from roughly $6 a share in 2000 to $100 a share today. Clearly, their business model can accommodate small-scale producers selling to a different customer base. In addition, it is often said that small businesses are a key economic driver. Small farms are small businesses. Freeing small farmers and entrepreneurs from onerous regulations that 40 other states do not have will help Mississippi’s economy grow.

Table taken from eXtension Foundation as adapted from USDA FSIS guidebook.

[1]Cf. definition of “retail food establishment” at § 69-1-18: “‘Retail food establishment’ means any establishment where food and food products are offered for sale to the ultimate consumer and intended for off-premise consumption.” Under this section, MDAC rules at 100.04 require “all poultry products offered for sale at a retail food establishment” to be slaughtered and processed according to state/federal guidelines. Thus, “no retail food establishment’ may sell poultry provided by a farmer actually operating under the 20,000 bird exemption. Cf. http://www.sos.ms.gov/ACCode/00000093c.pdf

[2]In the late 1960s, under the Johnson administration, the federal government forced states to follow federal inspection guidelines, even for products not entering interstate commerce – that is, products produced and sold only within the boundaries of a single state. The “Meat Act” included various “personal use” exemptions for custom slaughterhouses. The “Poultry Act” also allowed for conditional exemptions for small producers and businesses – i.e., the 1,000 and 20,000 bird exemptions. Exempt operators are NOT exempt from all federal requirements. They are exempt from continuous bird-by-bird inspection, and accordingly, the daily presence of a federal inspector. In other words, the 1,000 and 20,000 bird allowances exempt the processor from mandatory inspection. Federal law also permits a small enterprise exemption that allows a restauranteur, for instance, to purchase live chickens and then slaughter, dress and sell them to customers. It is unclear whether Mississippi allows this practice. For more information from FSIS, see the PowerPoint presentation by Robert Ragland, “Poultry Exemptions Under the Federal Poultry Products Inspection Act.”